Charlie Munger – The Architect of Berkshire Hathaway

Charlie Munger died on November 28, just 33 days before his 100th birthday.

Though born and raised in Omaha, he spent 80% of his life domiciled

elsewhere. Consequently, it was not until 1959 when he was 35 that I first met him.

In 1962, he decided that he should take up money management.

Three years later he told me – correctly! – that I had made a dumb decision in

buying control of Berkshire. But, he assured me, since I had already made the move,

he would tell me how to correct my mistake.

In what I next relate, bear in mind that Charlie and his family did not have a

dime invested in the small investing partnership that I was then managing and whose

money I had used for the Berkshire purchase. Moreover, neither of us expected that

Charlie would ever own a share of Berkshire stock.

Nevertheless, Charlie, in 1965, promptly advised me: “Warren, forget about

ever buying another company like Berkshire. But now that you control Berkshire, add

to it wonderful businesses purchased at fair prices and give up buying fair businesses

at wonderful prices. In other words, abandon everything you learned from your hero,

Ben Graham. It works but only when practiced at small scale.” With much back-sliding

I subsequently followed his instructions.

Many years later, Charlie became my partner in running Berkshire and,

repeatedly, jerked me back to sanity when my old habits surfaced. Until his death, he

continued in this role and together we, along with those who early on invested with

us, ended up far better off than Charlie and I had ever dreamed possible.

In reality, Charlie was the “architect” of the present Berkshire, and I acted as

the “general contractor” to carry out the day-by-day construction of his vision.

Charlie never sought to take credit for his role as creator but instead let me

take the bows and receive the accolades. In a way his relationship with me was part

older brother, part loving father. Even when he knew he was right, he gave me the

reins, and when I blundered he never – never –reminded me of my mistake.

In the physical world, great buildings are linked to their architect while those

who had poured the concrete or installed the windows are soon forgotten. Berkshire

has become a great company. Though I have long been in charge of the construction

crew; Charlie should forever be credited with being the architect.

2

�

BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC.

To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

Berkshire has more than three million shareholder accounts. I am charged with writing a

letter every year that will be useful to this diverse and ever-changing group of owners, many of

whom wish to learn more about their investment.

Charlie Munger, for decades my partner in managing Berkshire, viewed this obligation

identically and would expect me to communicate with you this year in the regular manner. He and

I were of one mind regarding our responsibilities to Berkshire shareholders.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Writers find it useful to picture the reader they seek, and often they are hoping to attract a

mass audience. At Berkshire, we have a more limited target: investors who trust Berkshire with

their savings without any expectation of resale (resembling in attitude people who save in order to

buy a farm or rental property rather than people who prefer using their excess funds to purchase

lottery tickets or “hot” stocks).

Over the years, Berkshire has attracted an unusual number of such “lifetime” shareholders

and their heirs. We cherish their presence and believe they are entitled to hear every year both the

good and bad news, delivered directly from their CEO and not from an investor-relations officer

or communications consultant forever serving up optimism and syrupy mush.

In visualizing the owners that Berkshire seeks, I am lucky to have the perfect mental model,

my sister, Bertie. Let me introduce her.

For openers, Bertie is smart, wise and likes to challenge my thinking. We have never,

however, had a shouting match or anything close to a ruptured relationship. We never will.

Furthermore, Bertie, and her three daughters as well, have a large portion of their savings

in Berkshire shares. Their ownership spans decades, and every year Bertie will read what I have

to say. My job is to anticipate her questions and give her honest answers.

3

�

Bertie, like most of you, understands many accounting terms, but she is not ready for a

CPA exam. She follows business news – reading four newspapers daily – but doesn’t consider

herself an economic expert. She is sensible – very sensible – instinctively knowing that pundits

should always be ignored. After all, if she could reliably predict tomorrow’s winners, would she

freely share her valuable insights and thereby increase competitive buying? That would be like

finding gold and then handing a map to the neighbors showing its location.

Bertie understands the power – for good or bad – of incentives, the weaknesses of humans,

the “tells” that can be recognized when observing human behavior. She knows who is “selling”

and who can be trusted. In short, she is nobody’s fool.

So, what would interest Bertie this year?

Operating Results, Fact and Fiction

Let’s begin with the numbers. The official annual report begins on K-1 and extends for 124

pages. It is filled with a vast amount of information – some important, some trivial.

Among its disclosures many owners, along with financial reporters, will focus on page

K-72. There, they will find the proverbial “bottom line” labeled “Net earnings (loss).” The

numbers read $90 billion for 2021, ($23 billion) for 2022 and $96 billion for 2023.

What in the world is going on?

You seek guidance and are told that the procedures for calculating these “earnings” are

promulgated by a sober and credentialed Financial Accounting Standards Board (“FASB”),

mandated by a dedicated and hard-working Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) and

audited by the world-class professionals at Deloitte & Touche (“D&T”). On page K-67, D&T pulls

no punches: “In our opinion, the financial statements . . . . . present fairly, in all material respects

(italics mine), the financial position of the Company . . . . . and the results of its operations . . . . .

for each of the three years in the period ended December 31, 2023 . . . . .”

So sanctified, this worse-than-useless “net income” figure quickly gets transmitted

throughout the world via the internet and media. All parties believe they have done their job – and,

legally, they have.

We, however, are left uncomfortable. At Berkshire, our view is that “earnings” should be a

sensible concept that Bertie will find somewhat useful – but only as a starting point – in

evaluating a business. Accordingly, Berkshire also reports to Bertie and you what we call

“operating earnings.” Here is the story they tell: $27.6 billion for 2021; $30.9 billion for 2022 and

$37.4 billion for 2023.

4

�

The primary difference between the mandated figures and the ones Berkshire prefers is that

we exclude unrealized capital gains or losses that at times can exceed $5 billion a day. Ironically,

our preference was pretty much the rule until 2018, when the “improvement” was mandated.

Galileo’s experience, several centuries ago, should have taught us not to mess with mandates from

on high. But, at Berkshire, we can be stubborn.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Make no mistake about the significance of capital gains: I expect them to be a very

important component of Berkshire’s value accretion during the decades ahead. Why else would

we commit huge dollar amounts of your money (and Bertie’s) to marketable equities just as I have

been doing with my own funds throughout my investing lifetime?

I can’t remember a period since March 11, 1942 – the date of my first stock purchase – that

I have not had a majority of my net worth in equities, U.S.-based equities. And so far, so good.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell below 100 on that fateful day in 1942 when I “pulled the

trigger.” I was down about $5 by the time school was out. Soon, things turned around and now that

index hovers around 38,000. America has been a terrific country for investors. All they have

needed to do is sit quietly, listening to no one.

It is more than silly, however, to make judgments about Berkshire’s investment value based

on “earnings” that incorporate the capricious day-by-day and, yes, even year-by-year movements

of the stock market. As Ben Graham taught me, “In the short run the market acts as a voting

machine; in the long run it becomes a weighing machine.”

What We Do

Our goal at Berkshire is simple: We want to own either all or a portion of businesses that

enjoy good economics that are fundamental and enduring. Within capitalism, some businesses will

flourish for a very long time while others will prove to be sinkholes. It’s harder than you would

think to predict which will be the winners and losers. And those who tell you they know the answer

are usually either self-delusional or snake-oil salesmen.

At Berkshire, we particularly favor the rare enterprise that can deploy additional capital at

high returns in the future. Owning only one of these companies – and simply sitting tight – can

deliver wealth almost beyond measure. Even heirs to such a holding can – ugh! – sometimes live

a lifetime of leisure.

We also hope these favored businesses are run by able and trustworthy managers, though

that is a more difficult judgment to make, however, and Berkshire has had its share

of disappointments.

5

�

In 1863, Hugh McCulloch, the first Comptroller of the United States, sent a letter to all

national banks. His instructions included this warning: “Never deal with a rascal under the

expectation that you can prevent him from cheating you.” Many bankers who thought they could

“manage” the rascal problem have learned the wisdom of Mr. McCulloch’s advice – and I have as

well. People are not that easy to read. Sincerity and empathy can easily be faked. That is as true

now as it was in 1863.

This combination of the two necessities I’ve described for acquiring businesses has for

long been our goal in purchases and, for a while, we had an abundance of candidates to evaluate.

If I missed one – and I missed plenty – another always came along.

Those days are long behind us; size did us in, though increased competition for purchases

was also a factor.

Berkshire now has – by far – the largest GAAP net worth recorded by any American

business. Record operating income and a strong stock market led to a yearend figure of $561

billion. The total GAAP net worth for the other 499 S&P companies – a who’s who of American

business – was $8.9 trillion in 2022. (The 2023 number for the S&P has not yet been tallied but is

unlikely to materially exceed $9.5 trillion.)

By this measure, Berkshire now occupies nearly 6% of the universe in which it operates.

Doubling our huge base is simply not possible within, say, a five-year period, particularly because

we are highly averse to issuing shares (an act that immediately juices net worth).

There remain only a handful of companies in this country capable of truly moving the

needle at Berkshire, and they have been endlessly picked over by us and by others. Some we can

value; some we can’t. And, if we can, they have to be attractively priced. Outside the U.S., there

are essentially no candidates that are meaningful options for capital deployment at Berkshire. All

in all, we have no possibility of eye-popping performance.

Nevertheless, managing Berkshire is mostly fun and always interesting. On the positive

side, after 59 years of assemblage, the company now owns either a portion or 100% of various

businesses that, on a weighted basis, have somewhat better prospects than exist at most large

American companies. By both luck and pluck, a few huge winners have emerged from a great

many dozens of decisions. And we now have a small cadre of long-time managers who never muse

about going elsewhere and who regard 65 as just another birthday.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Berkshire benefits from an unusual constancy and clarity of purpose. While we emphasize

treating our employees, communities and suppliers well – who wouldn’t wish to do so? – our

allegiance will always be to our country and our shareholders. We never forget that, though your

money is comingled with ours, it does not belong to us.

6

�

With that focus, and with our present mix of businesses, Berkshire should do a bit better

than the average American corporation and, more important, should also operate with materially

less risk of permanent loss of capital. Anything beyond “slightly better,” though, is wishful

thinking. This modest aspiration wasn’t the case when Bertie went all-in on Berkshire – but it

is now.

Our Not-So-Secret Weapon

Occasionally, markets and/or the economy will cause stocks and bonds of some large and

fundamentally good businesses to be strikingly mispriced. Indeed, markets can – and

will – unpredictably seize up or even vanish as they did for four months in 1914 and for a few days

in 2001. If you believe that American investors are now more stable than in the past, think back to

September 2008. Speed of communication and the wonders of technology facilitate instant

worldwide paralysis, and we have come a long way since smoke signals. Such instant panics won’t

happen often – but they will happen.

Berkshire’s ability to immediately respond to market seizures with both huge sums and

certainty of performance may offer us an occasional large-scale opportunity. Though the stock

market is massively larger than it was in our early years, today’s active participants are neither

more emotionally stable nor better taught than when I was in school. For whatever reasons, markets

now exhibit far more casino-like behavior than they did when I was young. The casino now resides

in many homes and daily tempts the occupants.

One fact of financial life should never be forgotten. Wall Street – to use the term in its

figurative sense – would like its customers to make money, but what truly causes its denizens’

juices to flow is feverish activity. At such times, whatever foolishness can be marketed will be

vigorously marketed – not by everyone but always by someone.

Occasionally, the scene turns ugly. The politicians then become enraged; the most flagrant

perpetrators of misdeeds slip away, rich and unpunished; and your friend next door becomes

bewildered, poorer and sometimes vengeful. Money, he learns, has trumped morality.

One investment rule at Berkshire has not and will not change: Never risk permanent loss

of capital. Thanks to the American tailwind and the power of compound interest, the arena in which

we operate has been – and will be – rewarding if you make a couple of good decisions during a

lifetime and avoid serious mistakes.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

I believe Berkshire can handle financial disasters of a magnitude beyond any heretofore

experienced. This ability is one we will not relinquish. When economic upsets occur, as they will,

Berkshire’s goal will be to function as an asset to the country – just as it was in a very minor way

in 2008-9 – and to help extinguish the financial fire rather than to be among the many companies

that, inadvertently or otherwise, ignited the conflagration.

7

�

Our goal is realistic. Berkshire’s strength comes from its Niagara of diverse earnings

delivered after interest costs, taxes and substantial charges for depreciation and amortization

(“EBITDA” is a banned measurement at Berkshire). We also operate with minimal requirements

for cash, even if the country encounters a prolonged period of global economic weakness, fear and

near-paralysis.

Berkshire does not currently pay dividends, and its share repurchases are 100%

discretionary. Annual debt maturities are never material.

Your company also holds a cash and U.S. Treasury bill position far in excess of what

conventional wisdom deems necessary. During the 2008 panic, Berkshire generated cash from

operations and did not rely in any manner on commercial paper, bank lines or debt markets. We

did not predict the time of an economic paralysis but we were always prepared for one.

Extreme fiscal conservatism is a corporate pledge we make to those who have joined us in

ownership of Berkshire. In most years – indeed in most decades – our caution will likely prove to

be unneeded behavior – akin to an insurance policy on a fortress-like building thought to be

fireproof. But Berkshire does not want to inflict permanent financial damage – quotational

shrinkage for extended periods can’t be avoided – on Bertie or any of the individuals who have

trusted us with their savings.

Berkshire is built to last.

Non-controlled Businesses That Leave Us Comfortable

Last year

I mentioned

long-duration partial-ownership

positions – Coca-Cola and American Express. These are not huge commitments like our Apple

position. Each only accounts for 4-5% of Berkshire’s GAAP net worth. But they are meaningful

assets and also illustrate our thought processes.

two of Berkshire’s

American Express began operations in 1850, and Coca-Cola was launched in an Atlanta

drug store in 1886. (Berkshire is not big on newcomers.) Both companies tried expanding into

unrelated areas over the years and both found little success in these attempts. In the past – but

definitely not now – both were even mismanaged.

But each was hugely successful in its base business, reshaped here and there as conditions

called for. And, crucially, their products “traveled.” Both Coke and AMEX became recognizable

names worldwide as did their core products, and the consumption of liquids and the need for

unquestioned financial trust are timeless essentials of our world.

8

�

During 2023, we did not buy or sell a share of either AMEX or Coke – extending our own

Rip Van Winkle slumber that has now lasted well over two decades. Both companies again

rewarded our inaction last year by increasing their earnings and dividends. Indeed, our share of

AMEX earnings in 2023 considerably exceeded the $1.3 billion cost of our long-ago purchase.

Both AMEX and Coke will almost certainly increase their dividends in 2024 – about 16%

in the case of AMEX – and we will most certainly leave our holdings untouched throughout the

year. Could I create a better worldwide business than these two enjoy? As Bertie will tell

you: “No way.”

Though Berkshire did not purchase shares of either company in 2023, your indirect

ownership of both Coke and AMEX increased a bit last year because of share repurchases we made

at Berkshire. Such repurchases work to increase your participation in every asset that Berkshire

owns. To this obvious but often overlooked truth, I add my usual caveat: All stock repurchases

should be price-dependent. What is sensible at a discount to business-value becomes stupid if done

at a premium.

The lesson from Coke and AMEX? When you find a truly wonderful business, stick with

it. Patience pays, and one wonderful business can offset the many mediocre decisions that

are inevitable.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

This year, I would like to describe two other investments that we expect to maintain

indefinitely. Like Coke and AMEX, these commitments are not huge relative to our resources.

They are worthwhile, however, and we were able to increase both positions during 2023.

At yearend, Berkshire owned 27.8% of Occidental Petroleum’s common shares and also

owned warrants that, for more than five years, give us the option to materially increase our

ownership at a fixed price. Though we very much like our ownership, as well as the option,

Berkshire has no interest in purchasing or managing Occidental. We particularly like its vast oil

and gas holdings in the United States, as well as its leadership in carbon-capture initiatives, though

the economic feasibility of this technique has yet to be proven. Both of these activities are very

much in our country’s interest.

Not so long ago, the U.S. was woefully dependent on foreign oil, and carbon capture had

no meaningful constituency. Indeed, in 1975, U.S. production was eight million barrels of

oil-equivalent per day (“BOEPD”), a level far short of the country’s needs. From the favorable

energy position that facilitated the U.S. mobilization in World War II, the country had retreated to

become heavily dependent on foreign – potentially unstable – suppliers. Further declines in oil

production were predicted along with future increases in usage.

9

�

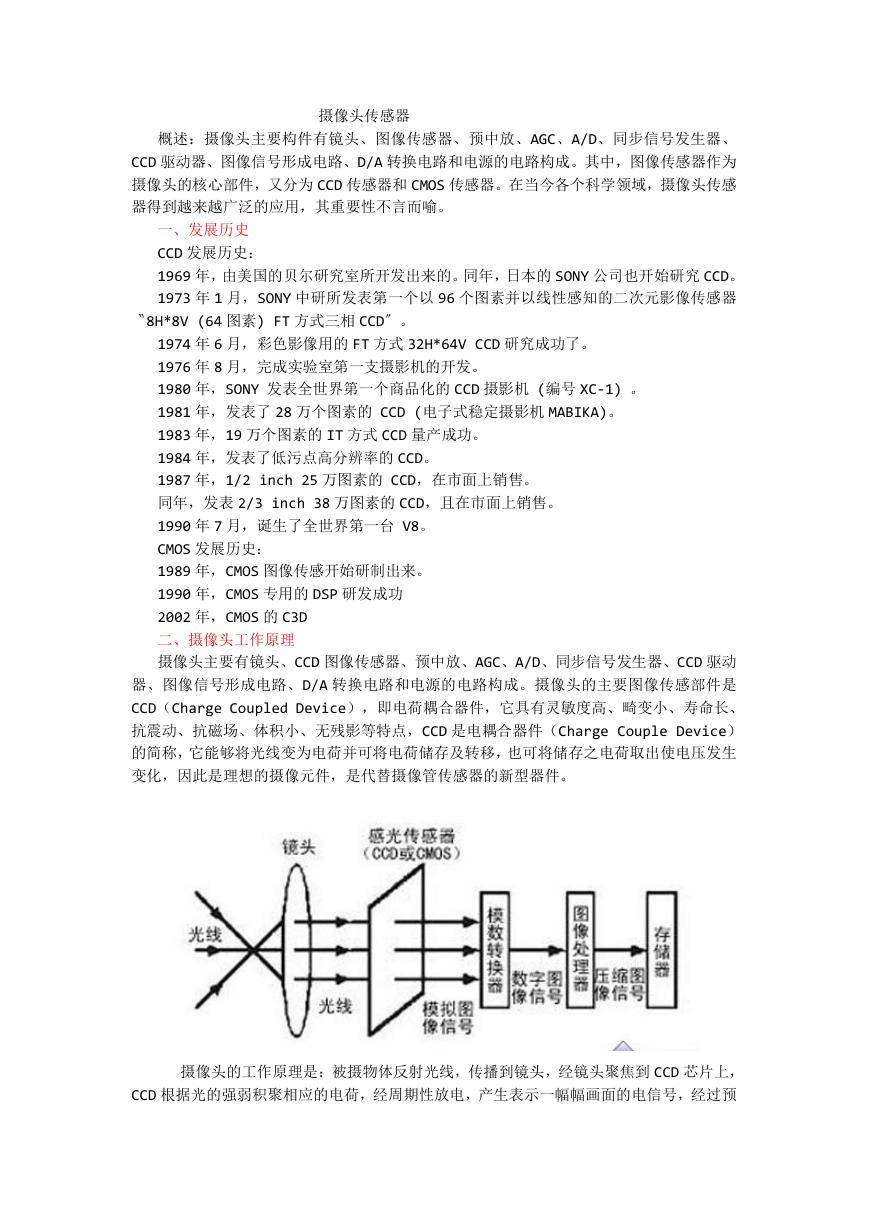

V2版本原理图(Capacitive-Fingerprint-Reader-Schematic_V2).pdf

V2版本原理图(Capacitive-Fingerprint-Reader-Schematic_V2).pdf 摄像头工作原理.doc

摄像头工作原理.doc VL53L0X简要说明(En.FLVL53L00216).pdf

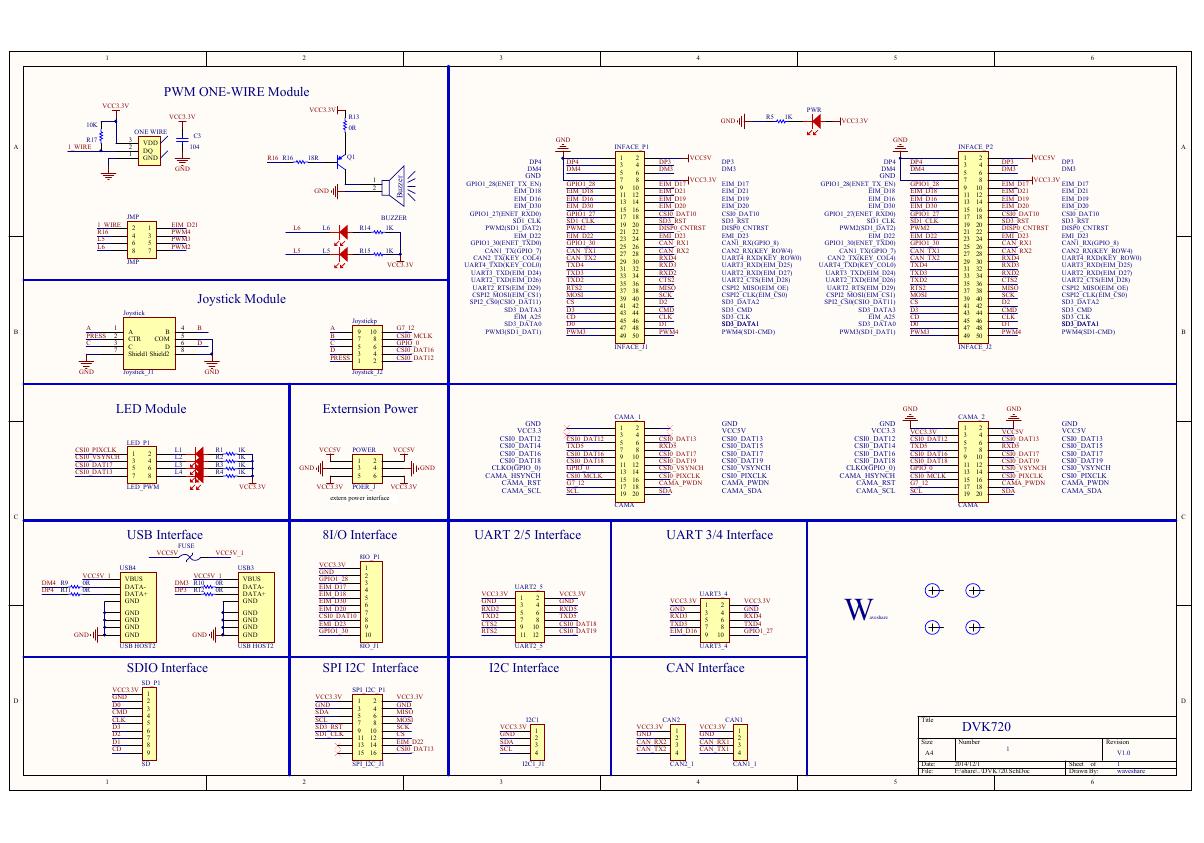

VL53L0X简要说明(En.FLVL53L00216).pdf 原理图(DVK720-Schematic).pdf

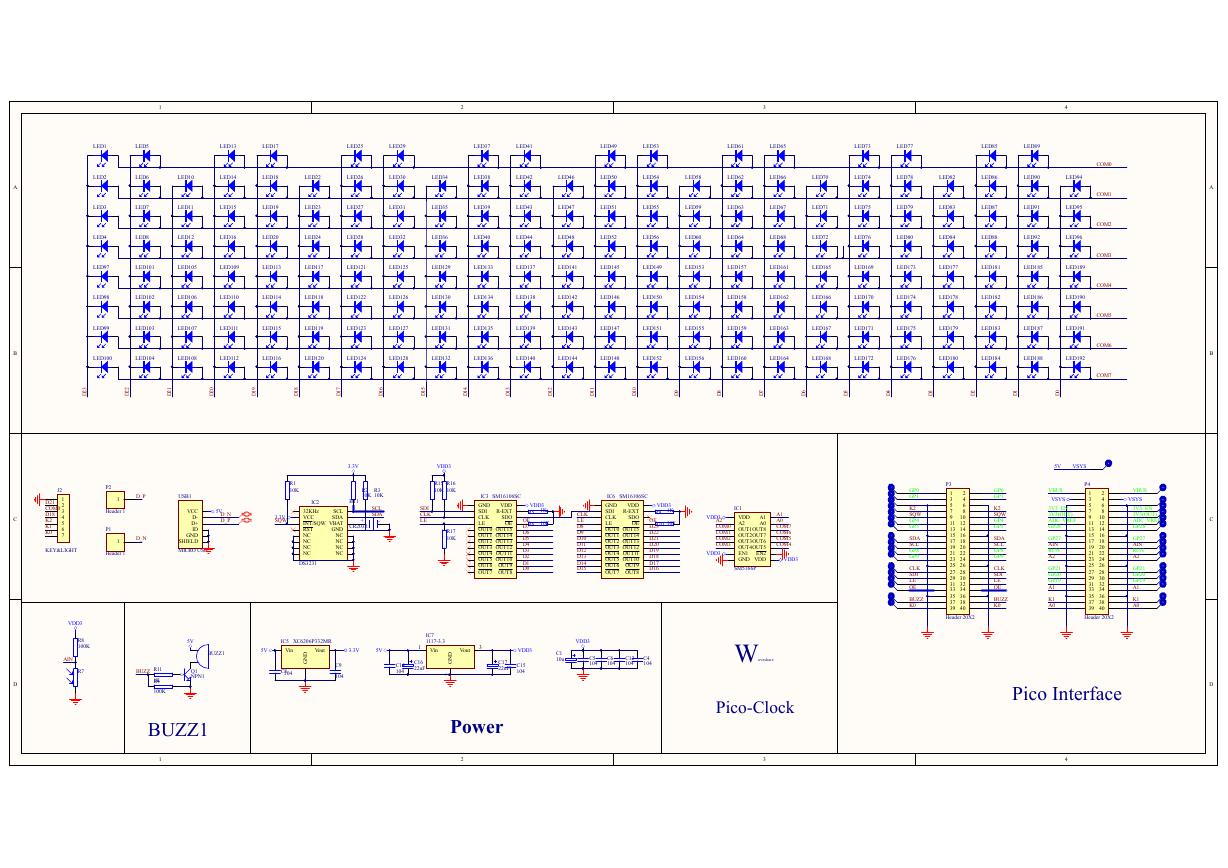

原理图(DVK720-Schematic).pdf 原理图(Pico-Clock-Green-Schdoc).pdf

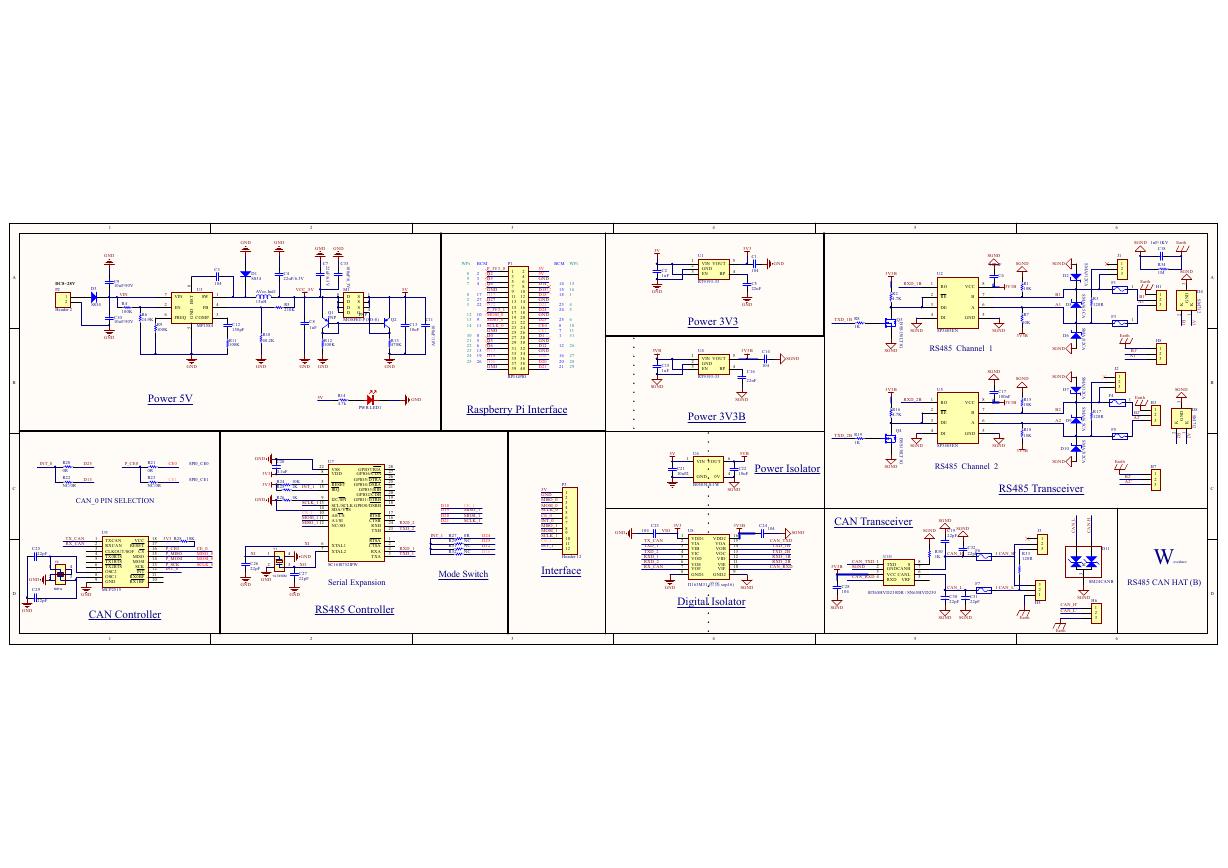

原理图(Pico-Clock-Green-Schdoc).pdf 原理图(RS485-CAN-HAT-B-schematic).pdf

原理图(RS485-CAN-HAT-B-schematic).pdf File:SIM7500_SIM7600_SIM7800 Series_SSL_Application Note_V2.00.pdf

File:SIM7500_SIM7600_SIM7800 Series_SSL_Application Note_V2.00.pdf ADS1263(Ads1262).pdf

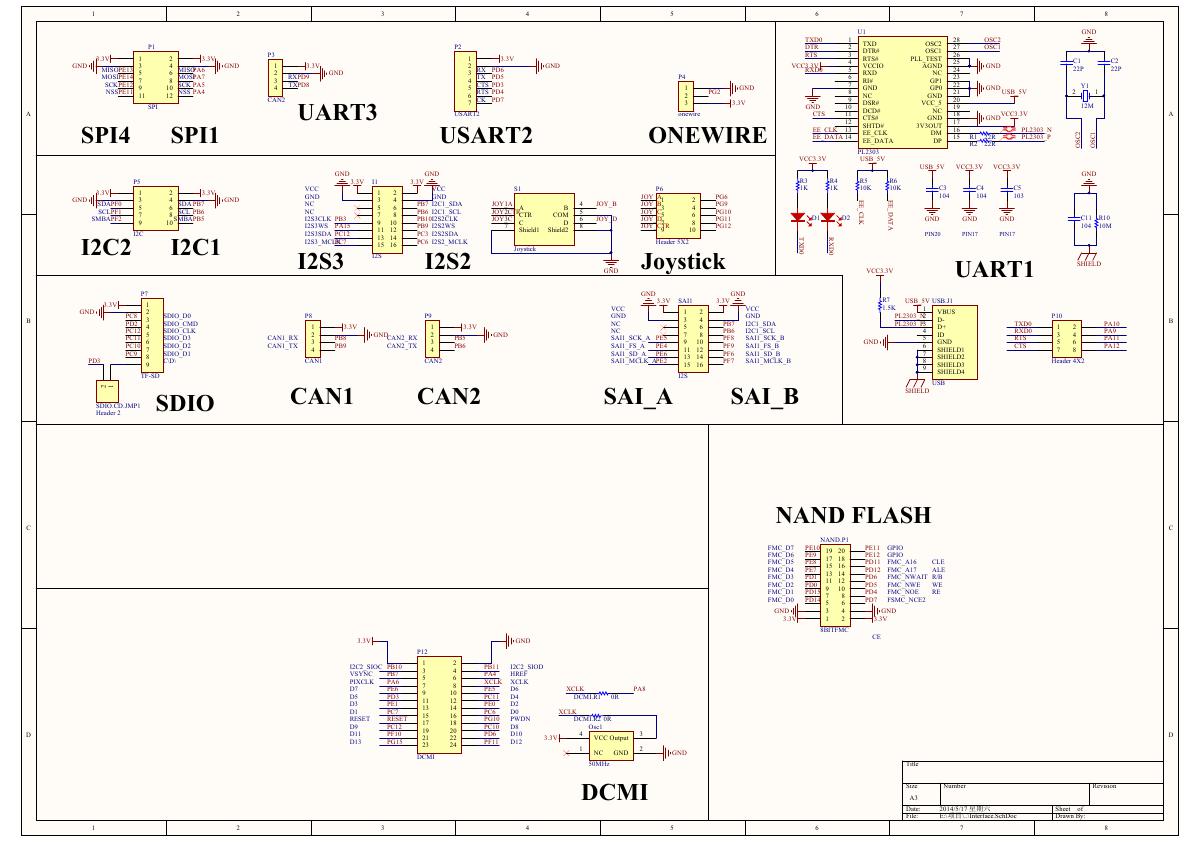

ADS1263(Ads1262).pdf 原理图(Open429Z-D-Schematic).pdf

原理图(Open429Z-D-Schematic).pdf 用户手册(Capacitive_Fingerprint_Reader_User_Manual_CN).pdf

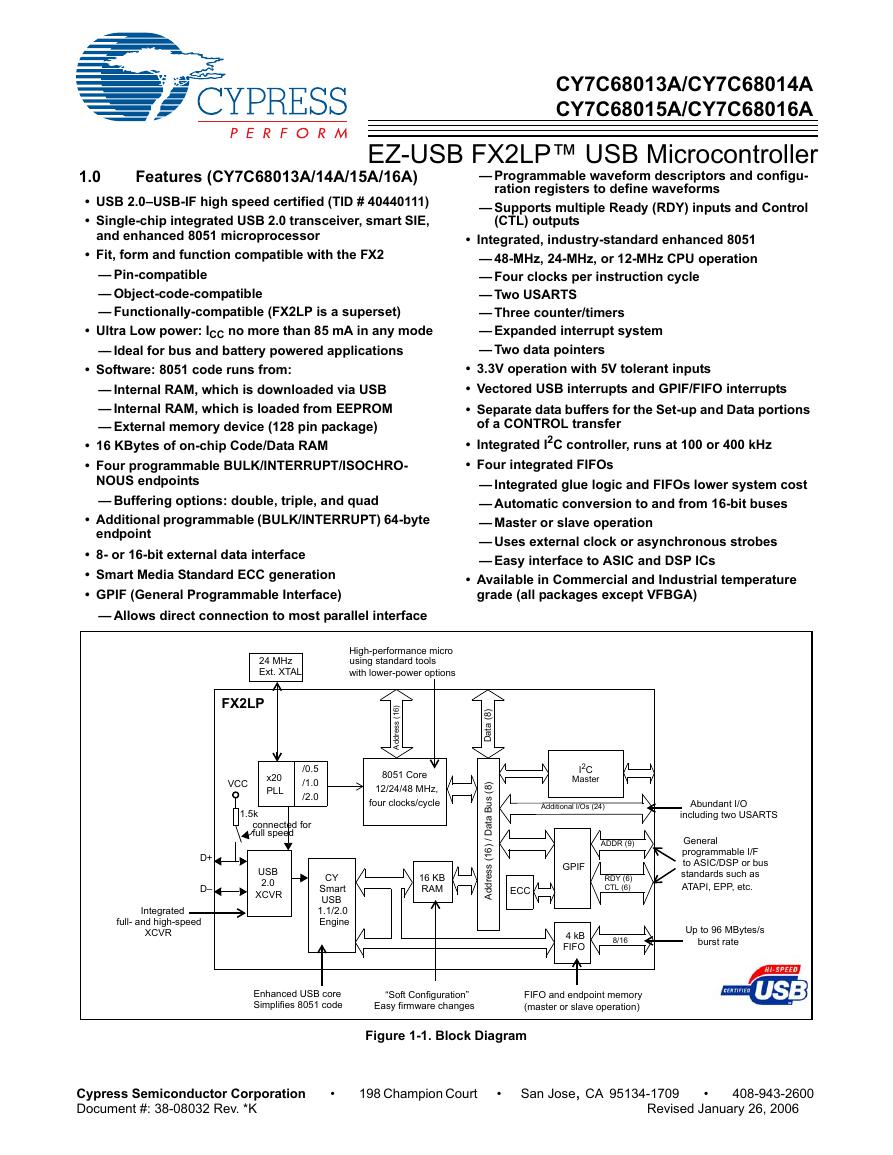

用户手册(Capacitive_Fingerprint_Reader_User_Manual_CN).pdf CY7C68013A(英文版)(CY7C68013A).pdf

CY7C68013A(英文版)(CY7C68013A).pdf TechnicalReference_Dem.pdf

TechnicalReference_Dem.pdf