The Apology

by Plato

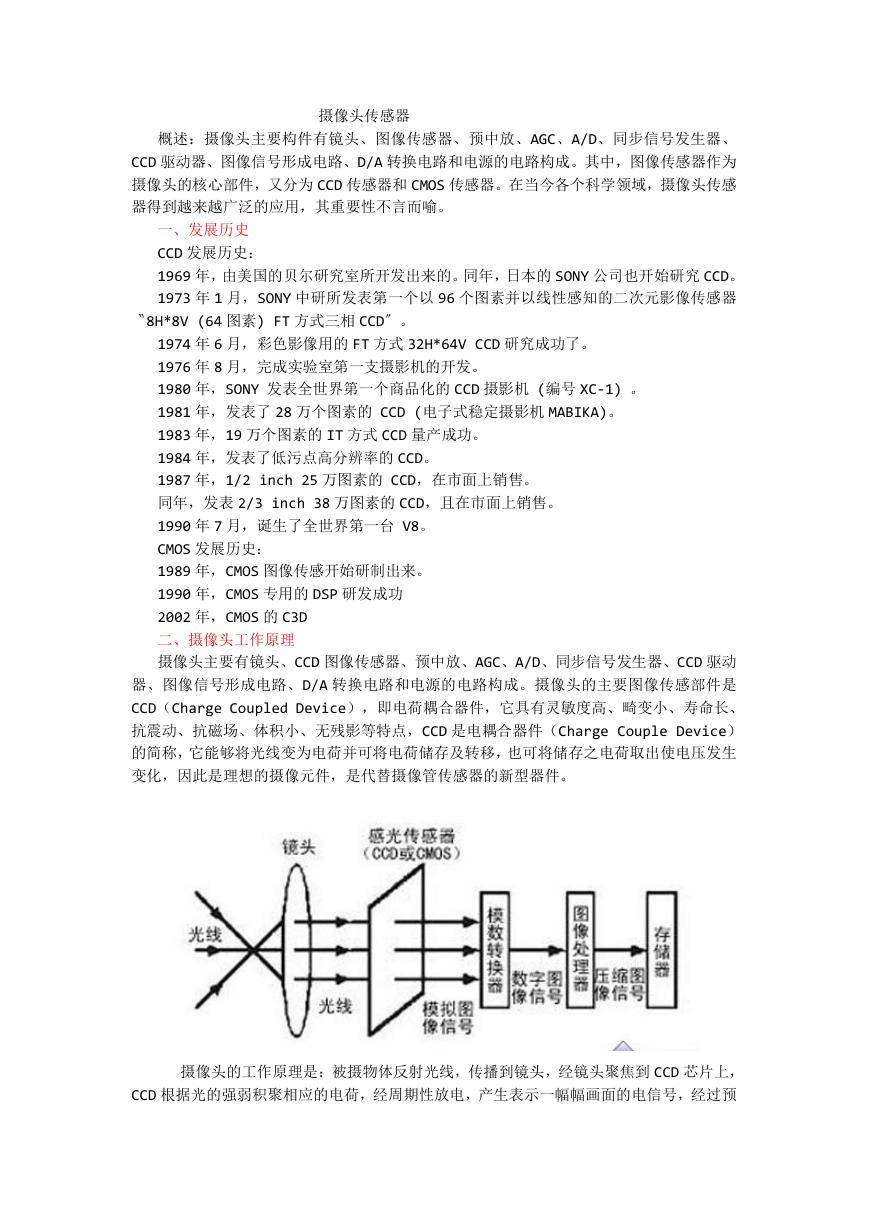

I do not know, men of Athens, how my

accusers affected you; as for me, I was almost

carried away in spite of myself, so persuasively

did they speak. And yet, hardly anything of

what they said is true. Of the many lies they

told, one in particular surprised me, namely

that you should be careful not to be deceived

by an accomplished speaker like me. That they

were not ashamed to be immediately proved

wrong by the facts, when I show myself not to

be an accomplished speaker at all, that I

thought was most shameless on

their

part—unless indeed they call an accomplished

speaker the man who speaks the truth. If they

Socrates, Roman mural 1 century

mean that, I would agree that I am an orator,

but not after their manner, for indeed, as I say, practically nothing they said was true. From me you

will hear the whole truth, though not, by Zeus, gentlemen, expressed in embroidered and stylized

phrases like theirs, but things spoken at random and expressed in the first words that come to mind,

for I put my trust in the justice of what I say, and let none of you expect anything else. It would

not be fitting at my age, as it might be for a young man, to toy with words when I appear before

you.

st

One thing I do ask and beg of you, gentlemen: if you hear me making my defence in the same

kind of language as I am accustomed to use in the market place by the bankers' tables, where many

of you have heard me, and elsewhere, do not be surprised or create a disturbance on that account.

The position is this: this is my first appearance in a lawcourt, at the age of seventy; I am therefore

simply a stranger to the manner of speaking here. Just as if I were really a stranger, you would

certainly excuse me if I spoke in that dialect and manner in which I had been brought up, so too

my present request seems a just one, for you to pay no attention to my manner of speech—be it

better or worse—but to concentrate your attention on whether what I say is just or not, for the

excellence of a judge lies in this, as that of a speaker lies in telling the truth.

It is right for me, gentlemen, to defend myself first against the first lying accusations made

against me and my first accusers, and then against the later accusations and the later accusers.

There have been many who have accused me to you for many years now, and none of their

accusations are true. These I fear much more than I fear Anytus and his friends, though they too

are formidable. These earlier ones, however, are more so, gentlemen; they got hold of most of you

from childhood, persuaded you and accused me quite falsely, saying that there is a man called

Socrates, a wise man, a student of all things in the sky and below the earth, who makes the worse

argument the stronger. Those who spread that rumour, gentlemen, are my dangerous accusers, for

their hearers believe that those who study these things do not even believe in the gods. Moreover,

these accusers are numerous, and have been at it a long time; also, they spoke to you at an age

when you would most readily believe them, some of you being children and adolescents, and they

won their case by default, as there was no defence.

17

b

c

d

18

b

c

�

Introduction to Western Philosophy

The Apology—2

What is most absurd in all this is that one cannot even know or mention their names unless one

of them is a writer of comedies. Those who maliciously and slanderously persuaded you—who

also, when persuaded themselves then persuaded others—all those are most difficult to deal with:

one cannot bring one of them into court or refute him; one must simply fight with shadows, as it

were, in making one's defence, and cross-examine when no one answers. I want you to realize too

that my accusers are of two kinds: those who have accused me recently, and the old ones I

mention; and to think that I must first defend myself against the latter, for you have also heard their

accusations first, and to a much greater extent than the more recent.

Very well then. I must surely defend myself and attempt to uproot from your minds in so short

a time the slander that has resided there so long. I wish this may happen, if it is in any way better

for you and me, and that my defence may be successful, but I think this is very difficult and I am

fully aware of how difficult it is. Even so, let the matter proceed as the god may wish, but I must

obey the law and make my defence.

d

e

19

b

c

d

e

20

b

c

Let us then take up the case from its beginning. What is the accusation from which arose the

slander in which Meletus trusted when he wrote out the charge against me? What did they say

when they slandered me? I must, as if they were my actual prosecutors, read the affidavit they

would have sworn. It goes something like this: Socrates is guilty of wrongdoing in that he busies

himself studying things in the sky and below the earth; he makes the worse into the stronger

argument, and he teaches these same things to others. You have seen this yourselves in the comedy

of Aristophanes, a Socrates swinging about there, saying he was walking on air and talking a lot

of other nonsense about things of which I know nothing at all. I do not speak in contempt of such

knowledge, if someone is wise in these things—lest Meletus bring more cases against me—but,

gentlemen, I have no part in it, and on this point I call upon the majority of you as witnesses. I

think it right that all those of you who have heard me conversing, and many of you have, should

tell each other if anyone of you has ever heard me discussing such subjects to any extent at all.

From this you will learn that the other things said about me by the majority are of the same kind.

Not one of them is true. And if you have heard from anyone that I undertake to teach people

and charge a fee for it, that is not true either. Yet I think it a fine thing to be able to teach people

as Gorgias of Leontini does, and Prodicus of Ceos, and Hippias of Elis. Each of these men can

go to any city and persuade the young, who can keep company with anyone of their own fellow-

citizens they want without paying, to leave the company of these, to join with themselves, pay

them a fee, and be grateful to them besides. Indeed, I learned that there is another wise man from

Paros who is visiting us, for I met a man who has spent more money on Sophists than everybody

else put together, Callias, the son of Hipponicus. So I asked him—he has two sons—"Callias," I

said, "if your sons were colts or calves, we could find and engage a supervisor for them who would

make them excel in their proper qualities, some horse breeder or farmer. Now since they are men,

whom do you have in mind to supervise them? Who is an expert in this kind of excellence, the

human and social kind? I think you must have given thought to this since you have sons. Is there

such a person," I asked, "or is there not?" "Certainly there is," he said. "Who is he?" I asked,

"What is his name, where is he from? and what is his fee?" "His name, Socrates, is Evenus, he

comes from Paras, and his fee is five minas." I thought Evenus a happy man, if he really possesses

this art, and teaches for so moderate a fee. Certainly I would pride and preen myself if I had this

knowledge, but I do not have it, gentlemen.

One of you might perhaps interrupt me and say: "But Socrates, what is your occupation? From

where have these slanders come? For surely if you did not busy yourself with something out of the

common, all these rumours and talk would not have arisen unless you did something other than

1

1. These were all well-known Sophists

�

Introduction to Western Philosophy

The Apology—3

most people. Tell us what it is, that we may not speak inadvisedly about you." Anyone who says

that seems to be right, and I will try to show you what has caused this reputation and slander.

Listen then. Perhaps some of you will think I am jesting, but be sure that all that I shall say is true.

What has caused my reputation is none other than a certain kind of wisdom. What kind of wisdom?

Human wisdom, perhaps. It may be that I really possess this, while those whom I mentioned just

now are wise with a wisdom more than human; else I cannot explain it, for I certainly do not

possess it, and whoever says I do is lying and speaks to slander me. Do not create a disturbance,

gentlemen, even if you think I am boasting, for the story I shall tell does not originate with me, but

I will refer you to a trustworthy source. I shall call upon the god at Delphi as witness to the

existence and nature of my wisdom, if it be such. You know Chairephon. He was my friend from

youth, and the friend of most of you, as he shared your exile and your return. You surely know the

kind of man he was, how impulsive in any course of action. He went to Delphi at one time and

ventured to ask the oracle—as I say, gentlemen, do not create a disturbance—he asked if any man

was wiser than I, and the Pythian replied that no one was wiser. Chairephon is dead, but his

brother will testify to you about this.

Consider that I tell you this because I would inform you about the origin of the slander. When

I heard of this reply I asked myself: "Whatever does the god mean? What is his riddle? I am very

conscious that I am not wise at all; what then does he mean by saying that I am the wisest? For

surely he does not lie; it is not legitimate for him to do so." For a long time I was at a loss as to his

meaning; then I very reluctantly turned to some such investigation as this: I went to one of those

reputed wise, thinking that there, if anywhere, I could refute the oracle and say to it: "This man

is wiser than I, but you said I was." Then, when I examined this man—there is no need for me to

tell you his name, he was one of our public men—my experience was something like this: I

thought that he appeared wise to many people and especially to himself, but he was not. I then

tried to show him that he thought himself wise, but that he was not. As a result he came to dislike

me, and so did many of the bystanders. So I withdrew and thought to myself: "I am wiser than this

man; it is likely that neither of us knows anything worthwhile, but he thinks he knows something

when he does not, whereas when I do not know, neither do I think I know; so I am likely to be

wiser than he to this small extent, that I do not think I know what I do not know." After this I

approached another man, one of those thought to be wiser than he, and I thought the same thing,

and so I came to be disliked both by him and by many others.

After that I proceeded systematically. I realized, to my sorrow and alarm, that I was getting

unpopular, but I thought that I must attach the greatest importance to the god's oracle, so I must

go to all those who had any reputation for knowledge to examine its meaning. And by the dog,

gentlemen of the jury—for I must tell you the truth—I experienced something like this: in my

investigation in the service of the god I found that those who had the highest reputation were

nearly the most deficient, while those who were thought to be inferior were more knowledgeable.

I must give you an account of my journeyings as if they were labours I had undertaken to prove

the oracle irrefutable. After the politicians, I went to the poets, the writers of tragedies and

dithyrambs and the others, intending in their case to catch myself being more ignorant then they.

So I took up those poems with which they seemed to have taken most trouble and asked them what

they meant, in order that I might at the same time learn something from them. I am ashamed to tell

you the truth, gentlemen, but I must. Almost all the bystanders might have explained the poems

better than their authors could. I soon realized that poets do not compose their poems with

knowledge, but by some inborn talent and by inspiration, like seers and prophets who also say

many fine things without any understanding of what they say. The poets seemed to me to have had

a similar experience. At the same time I saw that, because of their poetry, they thought themselves

very wise men in other respects, which they were not. So there again I withdrew, thinking that I

had the same advantage over them as I had over the politicians.

d

e

21

b

c

d

e

22

b

c

�

Introduction to Western Philosophy

The Apology—4

Finally I went to the craftsmen, for I was conscious of knowing practically nothing, and I knew

that I would find that they had knowledge of many fine things. In this I was not mistaken; they

knew things I did not know, and to that extent they were wiser than I. But, gentlemen of the jury,

the good craftsmen seemed to me to have the same fault as the poets: each of them, because of his

success at his craft, thought himself very wise in other most important pursuits, and this error of

theirs overshadowed the wisdom they had, so that I asked myself, on behalf of the oracle, whether

I should prefer to be as I am, with neither their wisdom nor their ignorance, or to have both. The

answer I gave myself and the oracle was that it was to my advantage to be as I am.

As a result of this investigation, gentlemen of the jury, I acquired much unpopularity, of a kind that

is hard to deal with and is a heavy burden; many slanders came from these people and a reputation

for wisdom, for in each case the bystanders thought that I myself possessed the wisdom that I

proved that my interlocutor did not have. What is probable, gentlemen, is that in fact the god is

wise and that his oracular response meant that human wisdom is worth little or nothing, and that

when he says this man, Socrates, he is using my name as an example, as if he said: "This man

among you, mortals, is wisest who, like Socrates, understands that his wisdom is worthless." So

even now I continue this investigation as the god bade me—and I go around seeking out anyone,

citizen or stranger, whom I think wise. Then if I do not think he is, I come to the assistance of the

god and show him that he is not wise. Because of this occupation, I do not have the leisure to

engage in public affairs to any extent, nor indeed to look after my own, but I live in great poverty

because of my service to the god.

Furthermore, the young men who follow me around of their own free will, those who have

most leisure, the sons of the very rich, take pleasure in hearing people questioned; they themselves

often imitate me and try to question others. I think they find an abundance of men who believe they

have some knowledge but know little or nothing. The result is that those whom they question are

angry, not with themselves but with me. They say: "That man Socrates is a pestilential fellow who

corrupts the young." If one asks them what he does and what he teaches to corrupt them, they are

silent, as they do not know, but, so as not to appear at a loss, they mention those accusations that

are available against all philosophers, about "things in the sky and things below the earth," about

"not believing in the gods" and "making the worse the stronger argument;" they would not want

to tell the truth, I'm sure, that they have been proved to lay claim to knowledge when they know

nothing. These people are ambitious, violent and numerous; they are continually and convincingly

talking about me; they have been filling your ears for a long time with vehement slanders against

me. From them Meletus attacked me, and Anytus and Lycon, Meletus being vexed on behalf of

the poets, Anytus on behalf of the craftsmen and the politicians, Lycon on behalf of the orators,

so that, as I started out by saying, I should be surprised if I could rid you of so much slander in so

short a time. That, gentlemen of the jury, is the truth for you. I have hidden or disguised nothing.

I know well enough that this very conduct makes me unpopular, and this is proof that what I say

is true, that such is the slander against me, and that such are its causes. If you look into this either

now or later, this is what you will find.

Let this suffice as a defence against the charges of my earlier accusers. After this I shall try

to defend myself against Meletus, that good and patriotic man, as he says he is, and my later

accusers. As these are a different lot of accusers, let us again take up their sworn deposition. It

goes something like this: Socrates is guilty of corrupting the young and of not believing in the gods

in whom the city believes, but in other new spiritual things. Such is their charge. Let us examine

it point by point.

He says that I am guilty of corrupting the young, but I say that Meletus is guilty of dealing

frivolously with serious matters, of irresponsibly bringing people into court, and of professing to

be seriously concerned with things about none of which he has ever cared, and I shall try to prove

d

e

23

b

c

d

e

24

b

c

�

Introduction to Western Philosophy

The Apology—5

that this is so. Come here and tell me, Meletus. Surely you consider it of the greatest importance

that our young men be as good as possible? —Indeed I do.

Come then, tell the jury who improves them. You obviously know, in view of your concern.

You say you have discovered the one who corrupts them, namely me, and you bring me here and

accuse me to the jury. Come, inform the jury and tell them who it is. You see, Meletus, that you

are silent and know not what to say. Does this not seem shameful to you and a sufficient proof of

what I say, that you have not been concerned with any of this? Tell me, my good sir, who improves

our young men? —The laws.

That is not what I am asking, but what person who has knowledge of the laws to begin

How do you mean, Meletus? Are these able to educate the young and improve

with?—These jurymen, Socrates.

them?—Certainly.

All of them, or some but not others?—All of them.

Very good, by Hera. You mention a great abundance of benefactors. But what about the

audience? Do they improve the young or not?—They do, too.

What about the members of Council?—The Councillors, also.

But, Meletus, what about the assembly? Do members of the assembly corrupt the young, or

do they all improve them?—They improve them.

All the Athenians, it seems, make the young into fine good men, except me, and I alone corrupt

them. Is that what you mean?—That is most definitely what I mean.

You condemn me to a great misfortune. Tell me: does this also apply to horses do you think?

That all men improve them and one individual corrupts them? Or is quite the contrary true, one

individual is able to improve them, or very few, namely the horse breeders, whereas the majority,

if they have horses and use them, corrupt them? Is that not the case, Meletus, both with horses and

all other animals? Of course it is, whether you and Anytus say so or not. It would be a very happy

state of affairs if only one person corrupted our youth, while the others improved them.

You have made it sufficiently obvious, Meletus, that you have never had any concern for our

youth; you show your indifference clearly; that you have given no thought to the subjects about

which you bring me to trial.

And by Zeus, Meletus, tell us also whether it is better for a man to live among good or wicked

fellow-citizens. Answer, my good man, for I am not asking a difficult question. Do not the wicked

do some harm to those who are ever closest to them, whereas good people benefit

them?—Certainly.

And does the man exist who would rather be harmed than benefited by his associates? Answer,

my good sir, for the law orders you to answer. Is there any man who wants to be harmed? —Of

course not.

Come now, do you accuse me here of corrupting the young and making them worse

deliberately or unwillingly?—Deliberately.

What follows, Meletus? Are you so much wiser at your age than I am at mine that you

understand that wicked people always do some harm to their closest neighbors while good people

do them good, but I have reached such a pitch of ignorance that I do not realize this, namely that

if I make one of my associates wicked I run the risk of being harmed by him so that I do such a

great evil deliberately, as you say? I do not believe you, Meletus, and I do not think anyone else

will. Either I do not corrupt the young or, if I do, it is unwillingly, and you are lying in either case.

Now if I corrupt them unwillingly, the law does not require you to bring people to court for such

unwilling wrongdoings, but to get hold of them privately, to instruct them and exhort them; for

clearly, if I learn better, I shall cease to do what I am doing unwillingly. You, however, have

avoided my company and were unwilling to instruct me, but you bring me here, where the law

requires one to bring those who are in need of punishment, not of instruction.

d

e

25

b

c

d

e

26

�

Introduction to Western Philosophy

The Apology—6

And so, gentlemen of the jury, what I said is clearly true: Meletus has never been at all

concerned with these matters. Nonetheless tell us, Meletus, how you say that I corrupt the young;

or is it obvious from your deposition that it is by teaching them not to believe in the gods in whom

the city believes but in other new spiritual things? Is this not what you say I teach and so corrupt

them? —That is most certainly what I do say.

b

c

d

e

27

b

c

d

e

Then by those very gods about whom we are talking, Meletus, make this clearer to me and to

the jury: I cannot be sure whether you mean that I teach the belief that there are some gods—and

therefore I myself believe that there are gods and am not altogether an atheist, nor am I guilty of

that—not, however, the gods in whom the city believes, but others, and that this is the charge

against me, that they are others. Or whether you mean that I do not believe in gods at all, and that

this is what I teach to others. —This is what I mean, that you do not believe in gods at all.

You are a strange fellow, Meletus. Why do you say this? Do I not believe, as other men do,

that the sun and the moon are gods?—No, by Zeus, jurymen, for he says that the sun is stone, and

the moon earth.

My dear Meletus, do you think you are prosecuting Anaxagoras? Are you so contemptuous

of the jury and think them so ignorant of letters as not to know that the books of Anaxagoras of

Clazomenae are full of those theories, and further, that the young men learn from me what they

can buy from time to time for a drachma, at most, in the bookshops, and ridicule Socrates if he

pretends that these theories are his own, especially as they are so absurd? Is that, by Zeus, what

you think of me, Meletus, that I do not believe that there are any gods? —That is what I say, that

you do not believe in the gods at all.

You cannot be believed, Meletus, even, I think, by yourself. The man appears to me,

gentlemen of the jury, highly insolent and uncontrolled. He seems to have made this deposition

out of insolence, violence and youthful zeal. He is like one who composed a riddle and is trying

it out: "Will the wise Socrates realize that I am jesting and contradicting myself, or shall I deceive

him and others?" I think he contradicts himself in the affidavit, as if he said: "Socrates is guilty of

not believing in gods but believing in gods," and surely that is the part of a jester!

Examine with me, gentlemen, how he appears to contradict himself, and you, Meletus, answer

us. Remember, gentlemen, what I asked you when I began, not to create a disturbance if I proceed

in my usual manner.

Does any man, Meletus, believe in human activities who does not believe in humans? Make

him answer, and not again and again create a disturbance. Does any man who does not believe in

horses believe in horsemen's activities? Or in flute-playing activities but not in flute-players? No,

my good sir, no man could. If you are not willing to answer, I will tell you and the jury. Answer

the next question, however. Does any man believe in spiritual activities who does not believe in

spirits?—No one.

Thank you for answering, if reluctantly, when the jury made you. Now you say that I believe

in spiritual things and teach about them, whether new or old, but at any rate spiritual things

according to what you say, and to this you have sworn in your deposition. But if I believe in

spiritual things I must quite inevitably believe in spirits. Is that not so? It is indeed. I shall assume

that you agree, as you do not answer. Do we not believe spirits to be either gods or the children

of gods? Yes or no?—Of course.

Then since I do believe in spirits, as you admit, if spirits are gods, this is what I mean when

I say you speak in riddles and in jest, as you state that I do not believe in gods and then again that

I do, since I do believe in spirits. If on the other hand the spirits are children of the gods, bastard

children of the gods by nymphs or some other mothers, as they are said to be, what man would

believe children of the gods to exist, but not gods? That would be just as absurd as to believe the

young of horses and asses, namely mules, to exist, but not to believe in the existence of horses and

asses. You must have made this deposition, Meletus, either to test us or because you were at a loss

�

Introduction to Western Philosophy

The Apology—7

to find any true wrongdoing of which to accuse me. There is no way in which you could persuade

anyone of even small intelligence that it is possible for one and the same man to believe in spiritual

but not also in divine things, and then again for that same man to believe neither in spirits nor in

gods nor in heroes.

2

28

b

c

d

e

29

b

c

I do not think, gentlemen of the jury, that it requires a prolonged defence to prove that I am

not guilty of the charges in Meletus' deposition, but this is sufficient. On the other hand, you know

that what I said earlier is true, that I am very unpopular with many people. This will be my

undoing, if I am undone, not Meletus or Anytus but the slanders and envy of many people. This

has destroyed many other good men and will, I think, continue to do so. There is no danger that

it will stop at me.

Someone might say: 'Are you not ashamed, Socrates, to have followed the kind of occupation

that has led to your being now in danger of death?" However, I should be right to reply to him:

"You are wrong, sir, if you think that a man who is any good at all should take into account the risk

of life or death; he should look to this only in his actions, whether what he does is right or wrong,

whether he is acting like a good or a bad man." According to your view, all the heroes who died

at Troy were inferior people, especially the son of Thetis who was so contemptuous of danger

compared with disgrace. When he was eager to kill Hector, his goddess mother warned him, as I

believe, in some such words as these: "My child, if you avenge the death of your comrade,

Patroclus, and you kill Hector, you will die yourself, for your death is to follow immediately after

Hector's." Hearing this, he despised death and danger and was much more afraid to live a coward

who did not avenge his friends. "Let me die at once," he said, "when once I have given the

wrongdoer his deserts, rather than remain here, a laughing-stock by the curved ships, a burden

upon the earth." Do you think he gave thought to death and danger?

This is the truth of the matter, gentlemen of the jury: wherever a man has taken a position that

he believes to be best, or has been placed by his commander, there he must I think remain and face

danger, without a thought for death or anything else, rather than disgrace. It would have been a

dreadful way to behave, gentlemen of the jury, if, at Potidaea, Amphipolis and Delium, I had, at

the risk of death, like anyone else, remained at my post where those you had elected to command

had ordered me, and then, when the god ordered me, as I thought and believed, to live "the life of

a philosopher, to examine myself and others, I had abandoned my post for fear of death or anything

else. That would have been a dreadful thing, and then I might truly have justly been brought here

for not believing that there are gods, disobeying the oracle, fearing death, and thinking I was wise

when I was not. To fear death, gentlemen, is no other than to think oneself wise when one is not,

to think one knows what one does not know. No one knows whether death may not be the greatest

of all blessings for a man, yet men fear it as if they knew that it is the greatest of evils. And surely

it is the most blameworthy ignorance to believe that one knows what one does not know. It is

perhaps on this point and in this respect, gentlemen, that I differ from the majority of men, and if

I were to claim that I am wiser than anyone in anything, it would be in this that as I have no

adequate knowledge of things in the underworld, so I do not think I have. I do know, however, that

it is wicked and shameful to do wrong, to disobey one's superior, be he god or man. I shall never

fear or avoid things of which I do not know, whether they may not be good rather than things that

I know to be bad. Even if you acquitted me now and did not believe Anytus, who said to you that

either I should not have been brought here in the first place, or that now I am here, you cannot

avoid executing me, for if I should be acquitted, your sons would practise the teachings of Socrates

and all be thoroughly corrupted; if you said to me in this regard: "Socrates, we do not believe

2. i.e., Achilles

�

Introduction to Western Philosophy

The Apology—8

Anytus now; we acquit you, but only on condition that you spend no more time on this

investigation and do not practise philosophy, and if you are caught doing so you will die;" if, as

I say, you were to acquit me on those terms, I would say to you: "Gentlemen of the jury, I am

grateful and I am your friend, but I will obey the god rather than you, and as long as I draw breath

and am able, I shall not cease to practise philosophy, to exhort you and in my usual way to point

out to anyone of you whom I happen to meet: Good Sir, you are an Athenian, a citizen of the

greatest city with the greatest reputation for both wisdom and power; are you not ashamed of your

eagerness to possess as much wealth, reputation and honours as possible, while you do not care

for nor give thought to wisdom or truth or the best possible state of your soul?" Then, if one of you

disputes this and says he does care, I shall not let him go at once or leave him, but I shall question

him, examine him and test him, and if I do not think he has attained the goodness that he says he

has, I shall reproach him because he attaches little importance to the most important things and

greater importance to inferior things. I shall treat in this way anyone I happen to meet, young and

old, citizen and stranger, and more so the citizens because you are more kindred to me. Be sure

that this is what the god orders me to do, and I think there is no greater blessing for the city than

my service to the god. For I go around doing nothing but persuading both young and old among

you not to care for your body or your wealth in preference to or as strongly as for the best possible

state of your soul, as I say to you: "Wealth does not bring about excellence, but excellence makes

wealth and everything else good for men, both individually and collectively."

Now if by saying this I corrupt the young, this advice must be harmful, but if anyone says that

I give different advice, he is talking nonsense. On this point I would say to you, gentlemen of the

jury: "Whether you believe Anytus or not, whether you acquit me or not, do so on the

understanding that this is my course of action, even if I am to face death many times." Do not

create a disturbance, gentlemen, but abide by my request not to cry out at what I say but to listen,

for I think it will be to your advantage to listen, and I am about to say other things at which you

will perhaps cry out. By no means do this. Be sure that if you kill the sort of man I say I am, you

will not harm me more than yourselves. Neither Meletus nor Anytus can harm me in any way; he

could not harm me, for I do not think it is permitted that a better man be harmed by a worse;

certainly he might kill me, or perhaps banish or disfranchise me, which he and maybe others think

to be great harm, but I do not think so. I think he is doing himself much greater harm doing what

he is doing now, attempting to have a man executed unjustly. Indeed, gentlemen of the jury, I am

far from making it defence now on my own behalf, as might be thought, but on yours, to prevent

you from wrongdoing by mistreating the god's gift to you by condemning me; for if you kill me

you will not easily find another like me. I was attached to this city by the god—though it seems

a ridiculous thing to say—as upon a great and noble horse which was somewhat sluggish because

of its size and needed to be stirred up by a kind of gadfly. It is to fulfill some such function that

I believe the god has placed me in the city. I never cease to rouse each and everyone of you, to

persuade and reproach you all day long and everywhere I find myself in your company.

Another such man will not easily come to be among you, gentlemen, and if you believe me you

will spare me. You might easily be annoyed with me as people are when they are aroused from a

doze, and strike out at me; if convinced by Anytus you could easily kill me, and then you could

sleep on for the rest of your days, unless the god, in his care for you, sent you someone else. That

I am the kind of person to be a gift of the god to the city you might realize from the fact that it does

not seem like human nature for me to have neglected all my own affairs and to have tolerated this

neglect now for so many years while I was always concerned with you, approaching each one of

you like a father or an elder brother to persuade you to care for virtue (aret). Now if I profited

from this by charging a fee for my advice, there would be some sense to it, but you can see for

yourselves that, for all their shameless accusations, my accusers have not been able in their

d

e

30

b

c

d

e

31

b

�

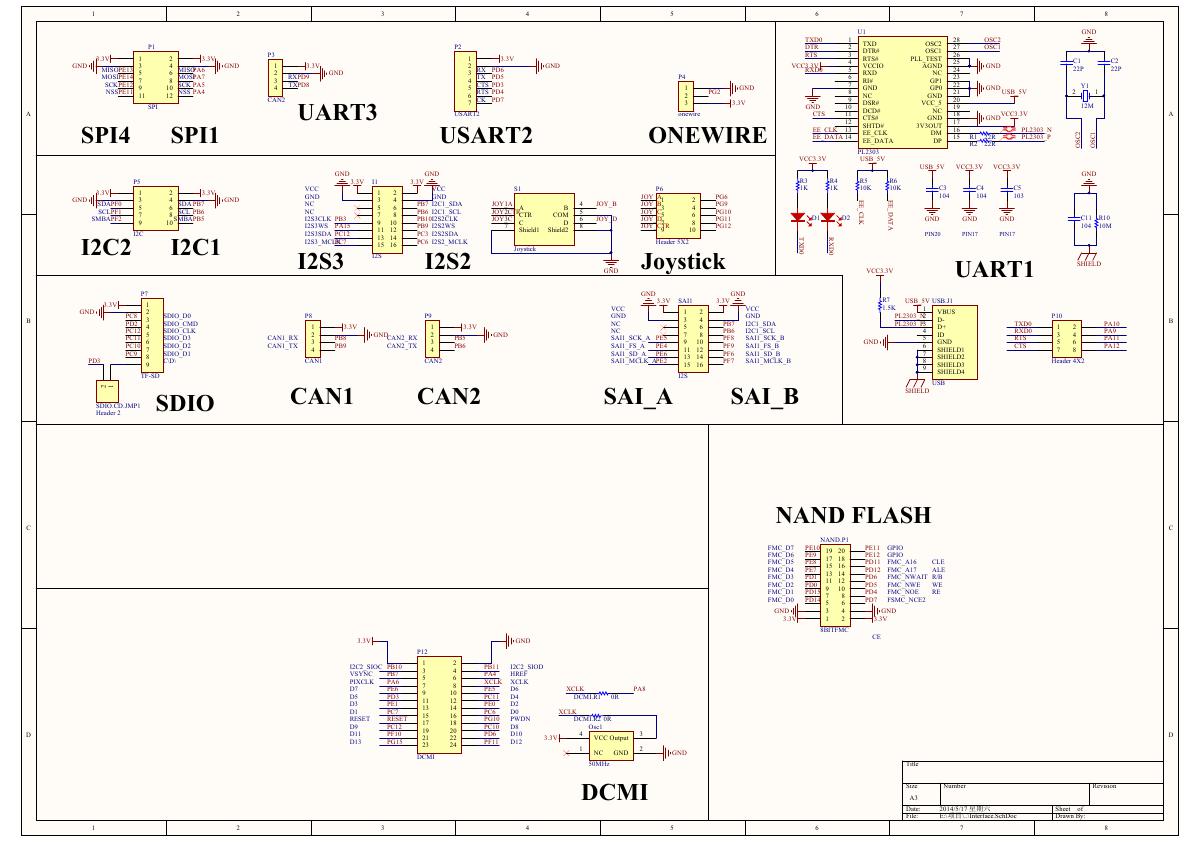

V2版本原理图(Capacitive-Fingerprint-Reader-Schematic_V2).pdf

V2版本原理图(Capacitive-Fingerprint-Reader-Schematic_V2).pdf 摄像头工作原理.doc

摄像头工作原理.doc VL53L0X简要说明(En.FLVL53L00216).pdf

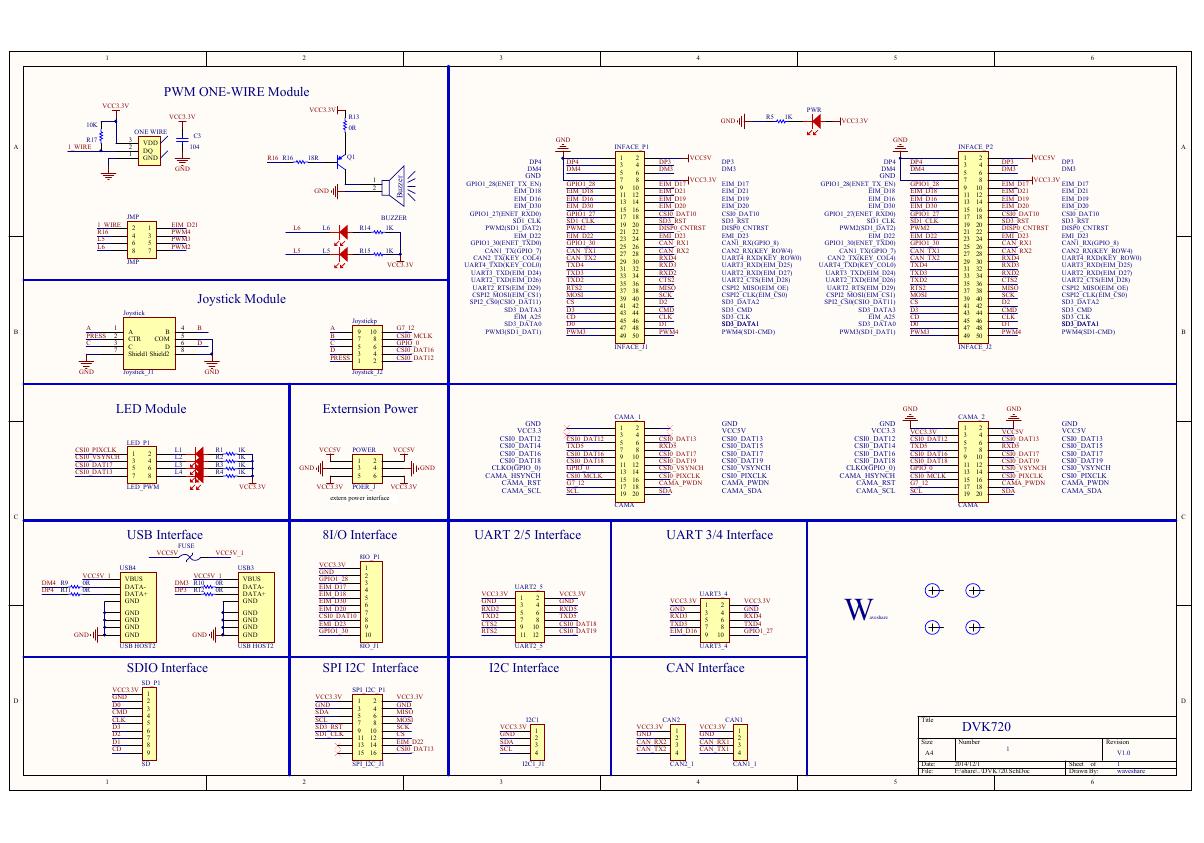

VL53L0X简要说明(En.FLVL53L00216).pdf 原理图(DVK720-Schematic).pdf

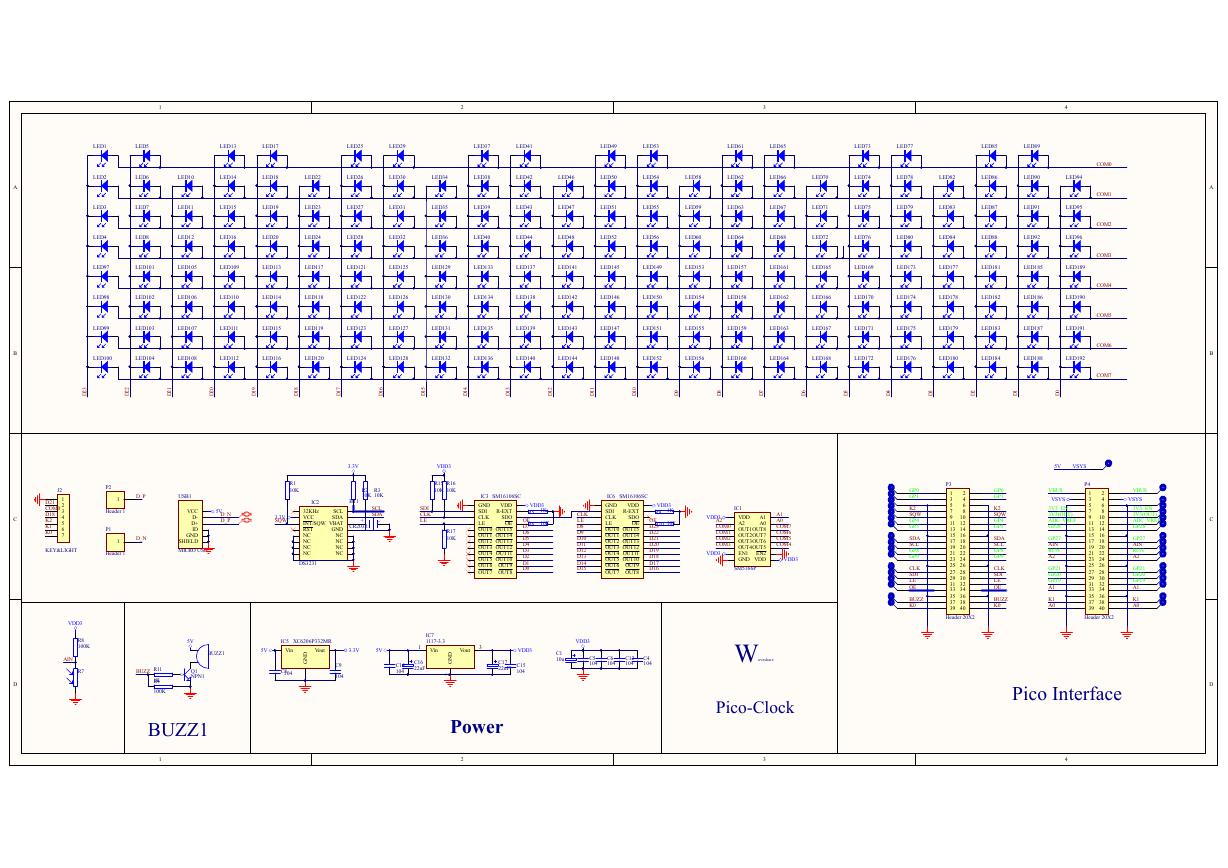

原理图(DVK720-Schematic).pdf 原理图(Pico-Clock-Green-Schdoc).pdf

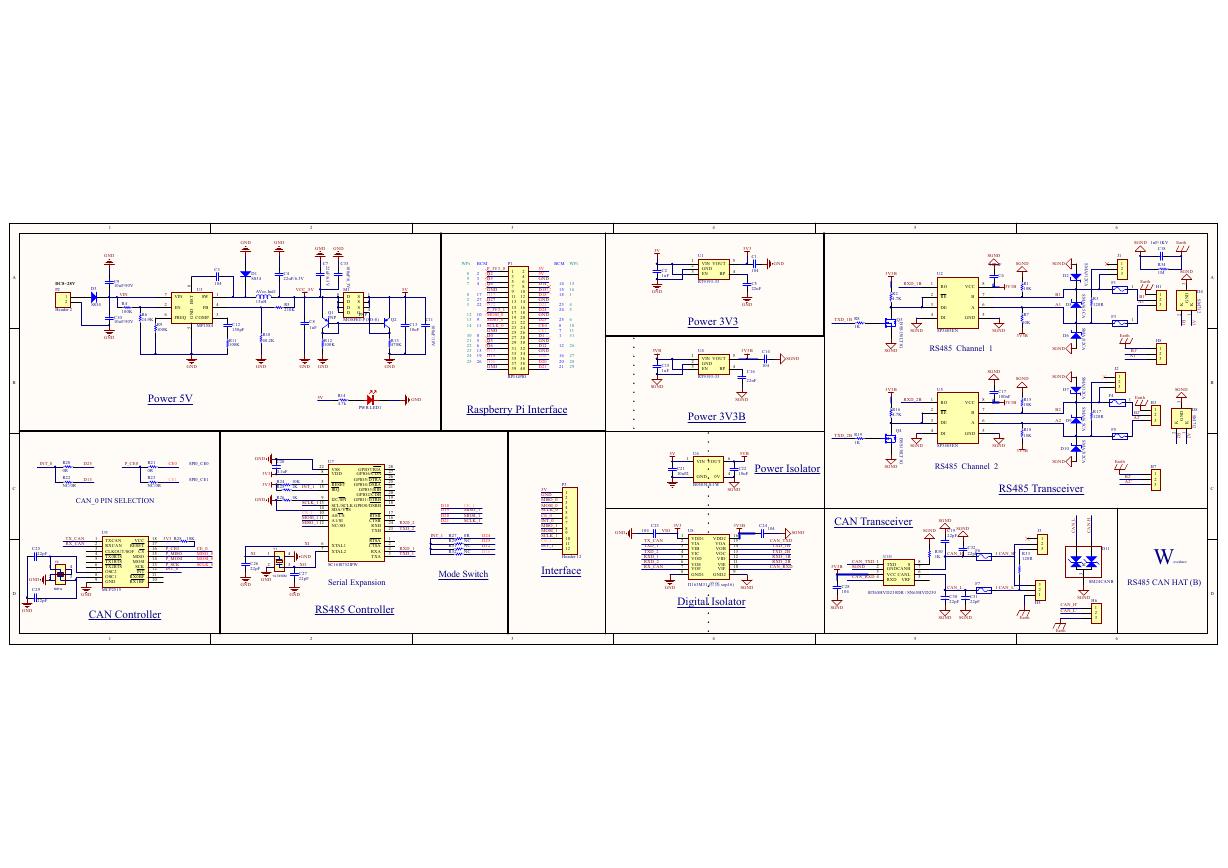

原理图(Pico-Clock-Green-Schdoc).pdf 原理图(RS485-CAN-HAT-B-schematic).pdf

原理图(RS485-CAN-HAT-B-schematic).pdf File:SIM7500_SIM7600_SIM7800 Series_SSL_Application Note_V2.00.pdf

File:SIM7500_SIM7600_SIM7800 Series_SSL_Application Note_V2.00.pdf ADS1263(Ads1262).pdf

ADS1263(Ads1262).pdf 原理图(Open429Z-D-Schematic).pdf

原理图(Open429Z-D-Schematic).pdf 用户手册(Capacitive_Fingerprint_Reader_User_Manual_CN).pdf

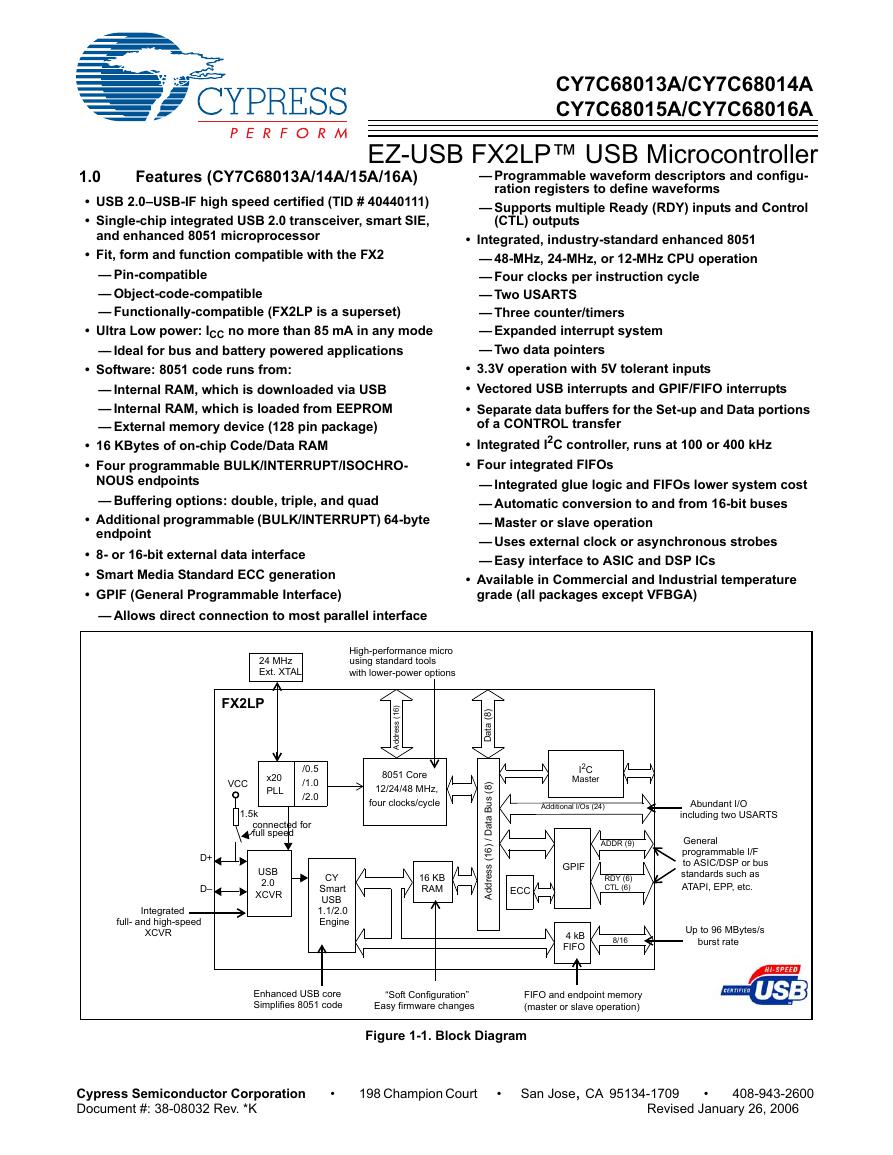

用户手册(Capacitive_Fingerprint_Reader_User_Manual_CN).pdf CY7C68013A(英文版)(CY7C68013A).pdf

CY7C68013A(英文版)(CY7C68013A).pdf TechnicalReference_Dem.pdf

TechnicalReference_Dem.pdf