Feature Denoising for Improving Adversarial Robustness

Cihang Xie1,2∗

Yuxin Wu2

1Johns Hopkins University

Laurens van der Maaten2

Alan Yuille1

2Facebook AI Research

Kaiming He2

9

1

0

2

r

a

M

5

2

]

V

C

.

s

c

[

2

v

1

1

4

3

0

.

2

1

8

1

:

v

i

X

r

a

Abstract

Adversarial attacks to image classification systems

present challenges to convolutional networks and oppor-

tunities for understanding them. This study suggests that

adversarial perturbations on images lead to noise in the

features constructed by these networks. Motivated by this

observation, we develop new network architectures that

increase adversarial robustness by performing feature

denoising. Specifically, our networks contain blocks that

denoise the features using non-local means or other filters;

the entire networks are trained end-to-end. When combined

with adversarial training, our feature denoising networks

substantially improve the state-of-the-art in adversarial

robustness in both white-box and black-box attack set-

tings. On ImageNet, under 10-iteration PGD white-box

attacks where prior art has 27.9% accuracy, our method

achieves 55.7%; even under extreme 2000-iteration PGD

white-box attacks, our method secures 42.6% accuracy.

Our method was ranked first in Competition on Adversarial

Attacks and Defenses (CAAD) 2018 — it achieved 50.6%

classification accuracy on a secret,

ImageNet-like test

dataset against 48 unknown attackers, surpassing the

runner-up approach by ∼10%.

Code is available at

https://github.com/facebookresearch/

ImageNet-Adversarial-Training.

1. Introduction

Adversarial attacks to image classification systems [20]

add small perturbations to images that lead these systems

into making incorrect predictions. While the perturba-

tions are often imperceptible or perceived as small “noise”

in the image,

these attacks are highly effective against

even the most successful convolutional network based sys-

tems [11, 14]. The success of adversarial attacks leads to

security threats in real-world applications of convolutional

networks, but equally importantly, it demonstrates that these

networks perform computations that are dramatically differ-

ent from those in human brains.

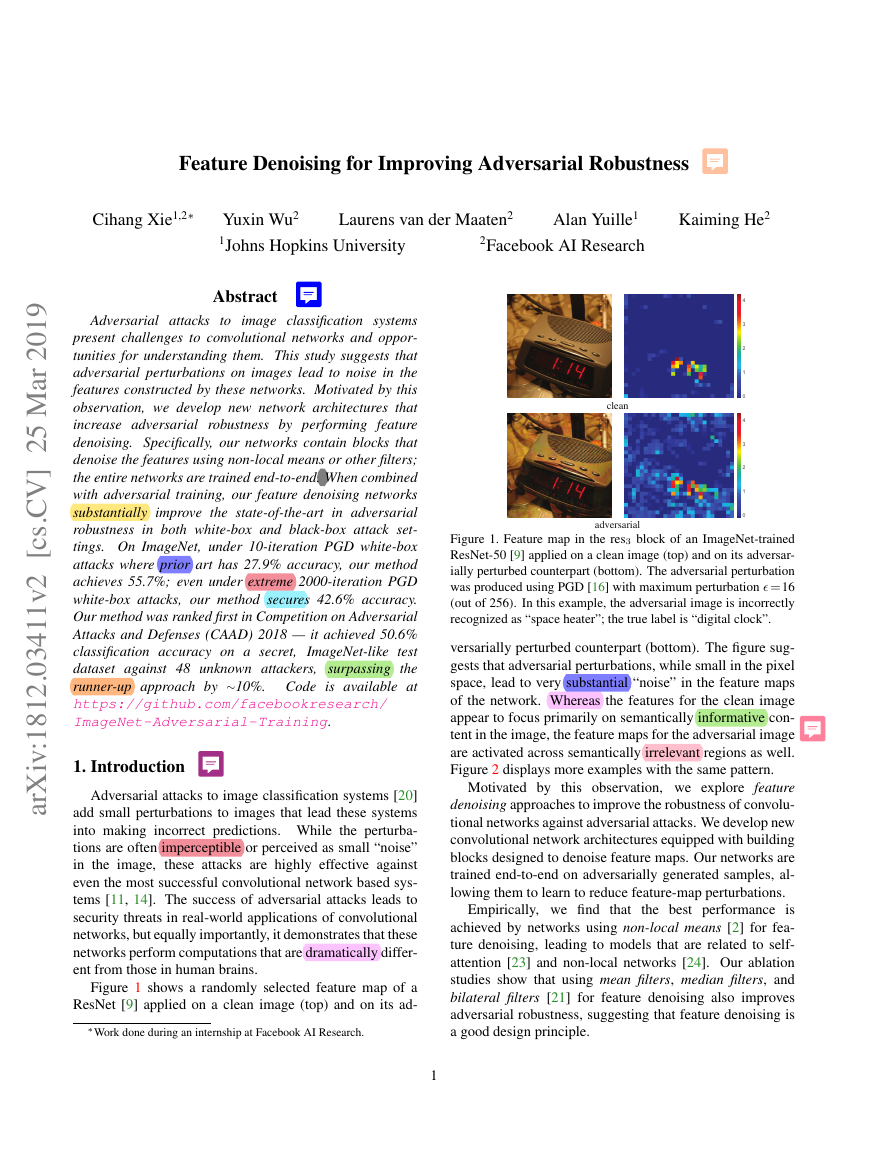

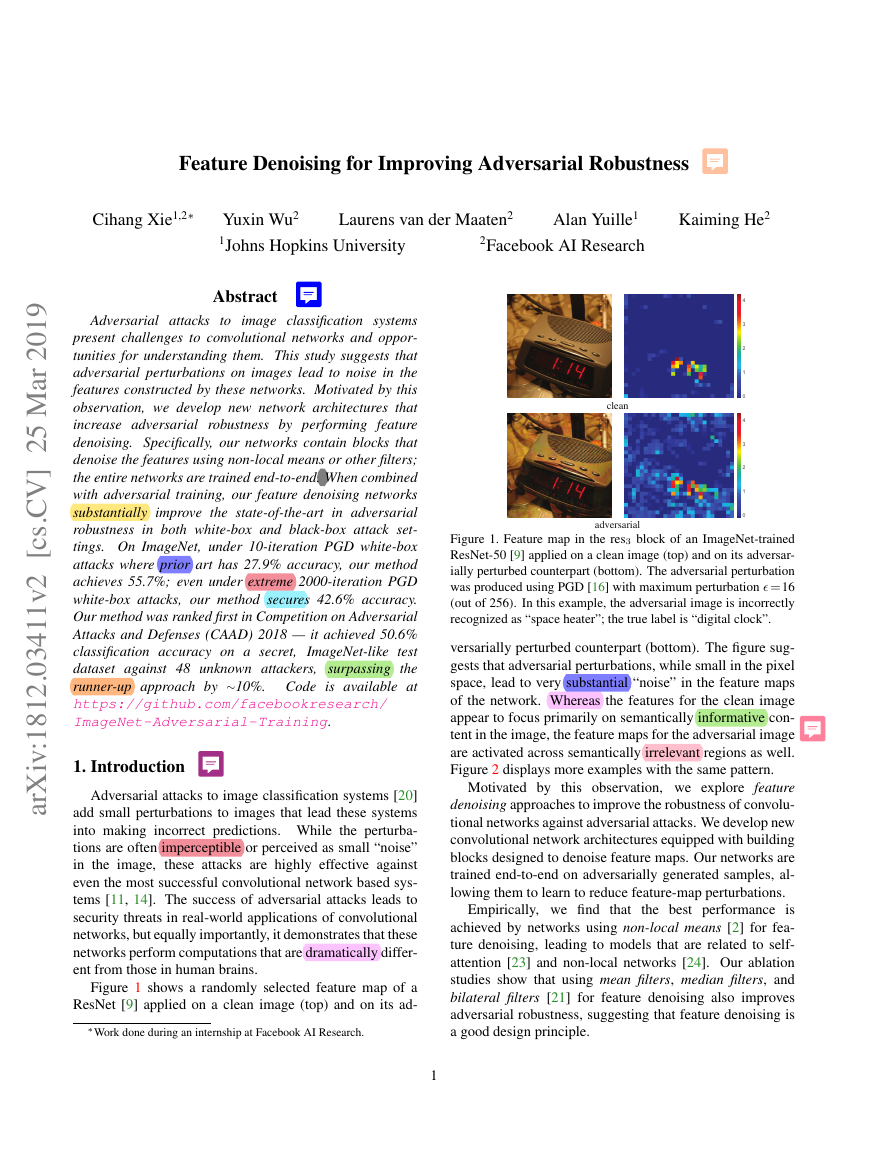

Figure 1 shows a randomly selected feature map of a

ResNet [9] applied on a clean image (top) and on its ad-

∗Work done during an internship at Facebook AI Research.

Figure 1. Feature map in the res3 block of an ImageNet-trained

ResNet-50 [9] applied on a clean image (top) and on its adversar-

ially perturbed counterpart (bottom). The adversarial perturbation

was produced using PGD [16] with maximum perturbation � =16

(out of 256). In this example, the adversarial image is incorrectly

recognized as “space heater”; the true label is “digital clock”.

versarially perturbed counterpart (bottom). The figure sug-

gests that adversarial perturbations, while small in the pixel

space, lead to very substantial “noise” in the feature maps

of the network. Whereas the features for the clean image

appear to focus primarily on semantically informative con-

tent in the image, the feature maps for the adversarial image

are activated across semantically irrelevant regions as well.

Figure 2 displays more examples with the same pattern.

Motivated by this observation, we explore feature

denoising approaches to improve the robustness of convolu-

tional networks against adversarial attacks. We develop new

convolutional network architectures equipped with building

blocks designed to denoise feature maps. Our networks are

trained end-to-end on adversarially generated samples, al-

lowing them to learn to reduce feature-map perturbations.

Empirically, we find that

the best performance is

achieved by networks using non-local means [2] for fea-

ture denoising, leading to models that are related to self-

attention [23] and non-local networks [24]. Our ablation

studies show that using mean filters, median filters, and

bilateral filters [21] for feature denoising also improves

adversarial robustness, suggesting that feature denoising is

a good design principle.

1

01234cleanadversarial01234�

Figure 2. More examples similar to Figure 1. We show feature maps corresponding to clean images (top) and to their adversarial perturbed

versions (bottom). The feature maps for each pair of examples are from the same channel of a res3 block in the same ResNet-50 trained on

clean images. The attacker has a maximum perturbation � = 16 in the pixel domain.

Our models outperform the state-of-the-art in adversarial

robustness against highly challenging white-box attacks on

ImageNet [18]. Under 10-iteration PGD attacks [16], we

report 55.7% classification accuracy on ImageNet, largely

surpassing the prior art’s 27.9% [10] with the same at-

tack protocol. Even when faced with extremely challeng-

ing 2000-iteration PGD attacks that have not been ex-

plored in other literature, our model achieves 42.6% accu-

racy. Our ablation experiments also demonstrate that fea-

ture denoising consistently improves adversarial defense re-

sults in white-box settings.

Our networks are also highly effective under the black-

box attack setting. The network based on our method won

the defense track in the recent Competition on Adversarial

Attacks and Defenses (CAAD) 2018, achieving 50.6% ac-

curacy against 48 unknown attackers, under a strict “all-or-

nothing” criterion. This is an 10% absolute (20% relative)

accuracy increase compared to the CAAD 2018 runner-up

model. We also conduct ablation experiments in which we

defend against the five strongest attackers from CAAD 2017

[13], demonstrating the potential of feature denoising.

2. Related Work

training

networks

by

Adversarial

training [6, 10, 16] defends against

perturbations

on

adversarial

images that are generated on-the-fly dur-

adversarial

ing training. Adversarial training constitutes the current

state-of-the-art in adversarial robustness against white-box

attacks; we use it to train our networks. Adversarial logit

paring (ALP) [10] is a type of adversarial training that

encourages the logit predictions of a network for a clean

image and its adversarial counterpart to be similar. ALP

can be interpreted as “denoising” the logit predictions for

the adversarial image, using the logits for the clean image

as the “noise-free” reference.

Other approaches to increase adversarial robustness in-

clude pixel denoising. Liao et al. [15] propose to use high-

level features to guide the pixel denoiser; in contrast, our

denoising is applied directly on features. Guo et al. [8]

transform the images via non-differentiable image prepro-

cessing, like image quilting [4], total variance minimiza-

tion [17], and quantization. While these defenses may be

effective in black-box settings, they can be circumvented

in white-box settings because the attacker can approximate

the gradients of their non-differentiable computations [1].

In contrast to [8], our feature denoising models are differ-

entiable, but are still able to improve adversarial robustness

against very strong white-box attacks.

3. Feature Noise

Adversarial images are created by adding perturbations

to images, constraining the magnitude of perturbations to

be small in terms of a certain norm (e.g., L∞ or L2). The

perturbations are assumed to be either imperceptible by hu-

mans, or perceived as noise that does not impede human

recognition of the visual content. Although the perturba-

tions are constrained to be small at the pixel level, no such

constraints are imposed at the feature level in convolutional

networks. Indeed, the perturbation of the features induced

by an adversarial image gradually increases as the image is

propagated through the network [15, 8], and non-existing

activations in the feature maps are hallucinated.

In other

words, the transformations performed by the layers in the

network exacerbate the perturbation, and the hallucinated

activations can overwhelm the activations due to the true

signal, which leads the network to make wrong predictions.

We qualitatively demonstrate these characteristics of

adversarial images by visualizing the feature maps they give

rise to. Given a clean image and its adversarially perturbed

counterpart, we use the same network (here, a ResNet-50

[9]) to compute its activations in the hidden layers. Figure 1

and 2 show typical examples of the same feature map on

clean and adversarial images, extracted from the middle of

the network (in particular, from a res3 block). These figures

01234012340123012301230123cleanadversarial�

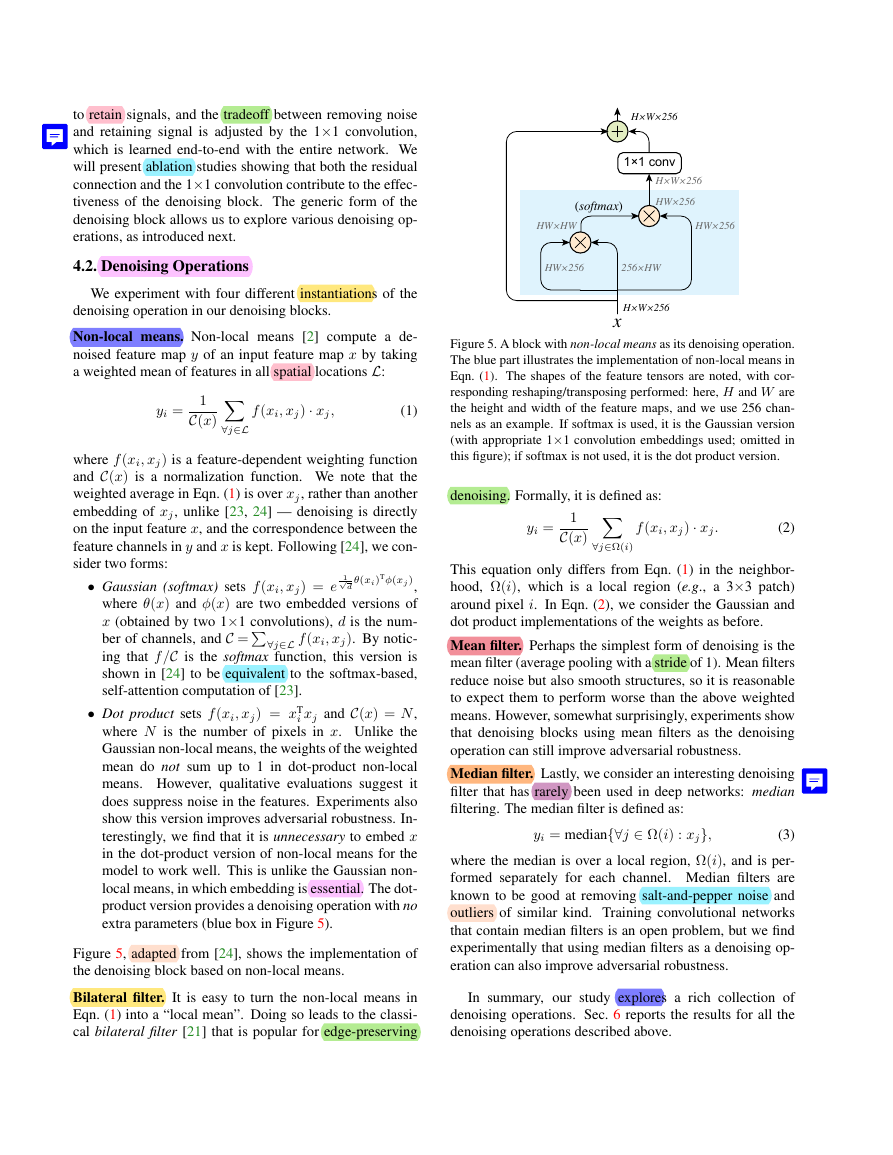

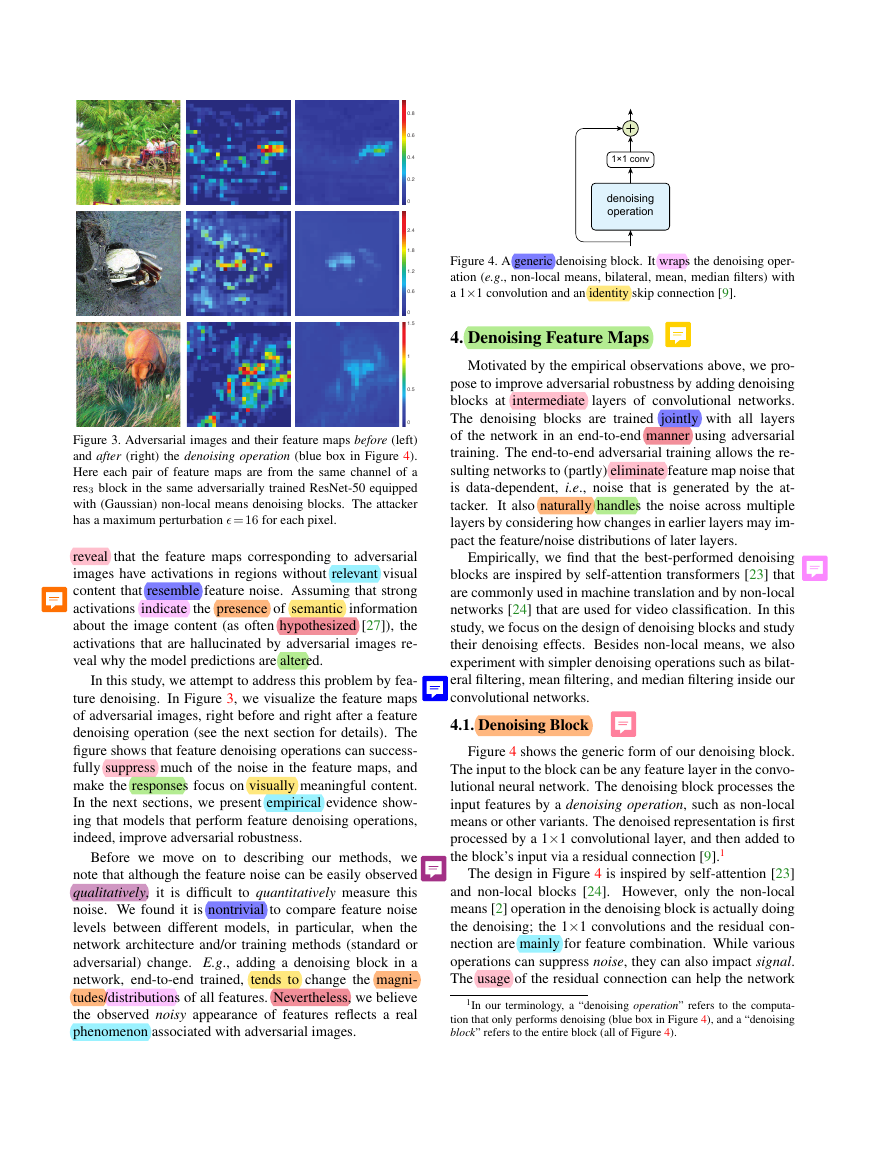

Figure 4. A generic denoising block. It wraps the denoising oper-

ation (e.g., non-local means, bilateral, mean, median filters) with

a 1×1 convolution and an identity skip connection [9].

4. Denoising Feature Maps

Motivated by the empirical observations above, we pro-

pose to improve adversarial robustness by adding denoising

blocks at intermediate layers of convolutional networks.

The denoising blocks are trained jointly with all layers

of the network in an end-to-end manner using adversarial

training. The end-to-end adversarial training allows the re-

sulting networks to (partly) eliminate feature map noise that

is data-dependent, i.e., noise that is generated by the at-

tacker. It also naturally handles the noise across multiple

layers by considering how changes in earlier layers may im-

pact the feature/noise distributions of later layers.

Empirically, we find that the best-performed denoising

blocks are inspired by self-attention transformers [23] that

are commonly used in machine translation and by non-local

networks [24] that are used for video classification. In this

study, we focus on the design of denoising blocks and study

their denoising effects. Besides non-local means, we also

experiment with simpler denoising operations such as bilat-

eral filtering, mean filtering, and median filtering inside our

convolutional networks.

4.1. Denoising Block

Figure 4 shows the generic form of our denoising block.

The input to the block can be any feature layer in the convo-

lutional neural network. The denoising block processes the

input features by a denoising operation, such as non-local

means or other variants. The denoised representation is first

processed by a 1×1 convolutional layer, and then added to

the block’s input via a residual connection [9].1

The design in Figure 4 is inspired by self-attention [23]

and non-local blocks [24]. However, only the non-local

means [2] operation in the denoising block is actually doing

the denoising; the 1×1 convolutions and the residual con-

nection are mainly for feature combination. While various

operations can suppress noise, they can also impact signal.

The usage of the residual connection can help the network

1In our terminology, a “denoising operation” refers to the computa-

tion that only performs denoising (blue box in Figure 4), and a “denoising

block” refers to the entire block (all of Figure 4).

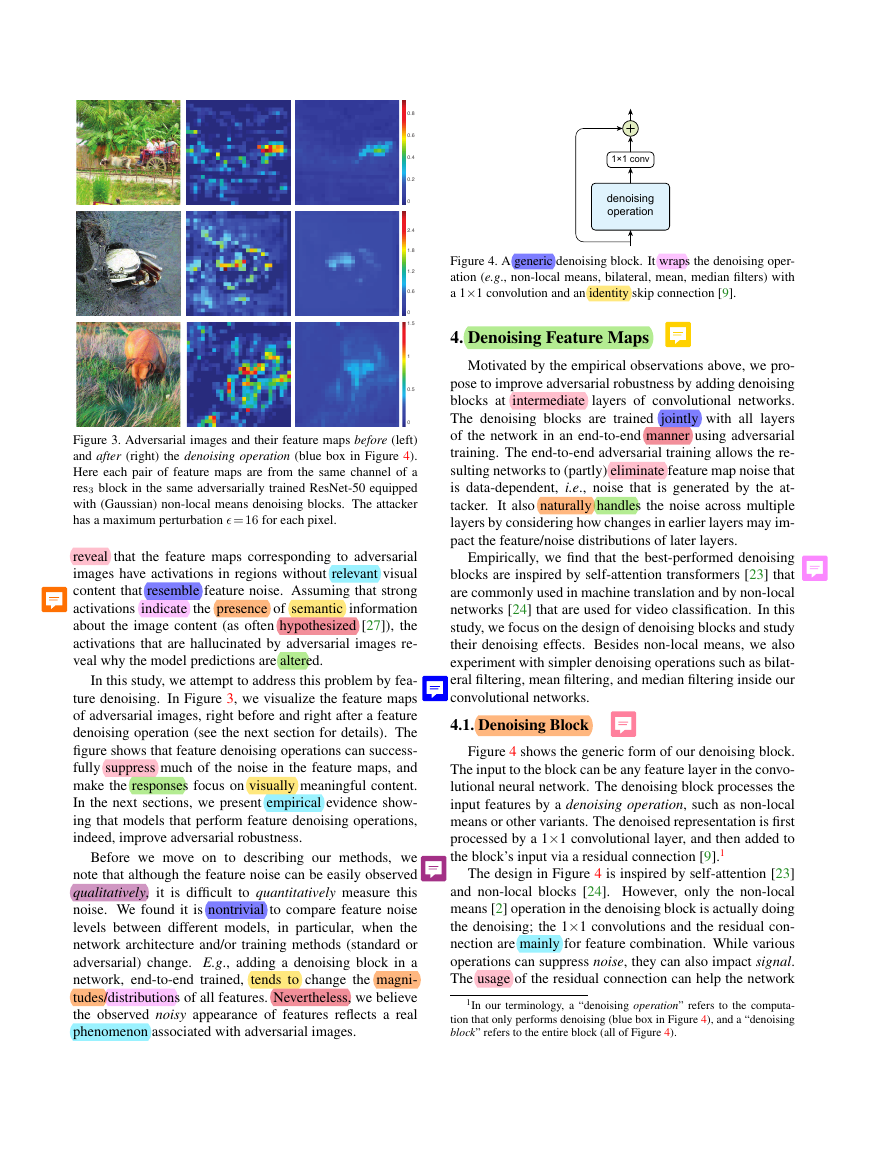

Figure 3. Adversarial images and their feature maps before (left)

and after (right) the denoising operation (blue box in Figure 4).

Here each pair of feature maps are from the same channel of a

res3 block in the same adversarially trained ResNet-50 equipped

with (Gaussian) non-local means denoising blocks. The attacker

has a maximum perturbation � = 16 for each pixel.

reveal that the feature maps corresponding to adversarial

images have activations in regions without relevant visual

content that resemble feature noise. Assuming that strong

activations indicate the presence of semantic information

about the image content (as often hypothesized [27]), the

activations that are hallucinated by adversarial images re-

veal why the model predictions are altered.

In this study, we attempt to address this problem by fea-

ture denoising. In Figure 3, we visualize the feature maps

of adversarial images, right before and right after a feature

denoising operation (see the next section for details). The

figure shows that feature denoising operations can success-

fully suppress much of the noise in the feature maps, and

make the responses focus on visually meaningful content.

In the next sections, we present empirical evidence show-

ing that models that perform feature denoising operations,

indeed, improve adversarial robustness.

Before we move on to describing our methods, we

note that although the feature noise can be easily observed

qualitatively, it is difficult to quantitatively measure this

noise. We found it is nontrivial to compare feature noise

levels between different models, in particular, when the

network architecture and/or training methods (standard or

adversarial) change. E.g., adding a denoising block in a

network, end-to-end trained, tends to change the magni-

tudes/distributions of all features. Nevertheless, we believe

the observed noisy appearance of features reflects a real

phenomenon associated with adversarial images.

00.20.40.60.800.511.500.61.21.82.41×1 convdenoisingoperation�

to retain signals, and the tradeoff between removing noise

and retaining signal is adjusted by the 1×1 convolution,

which is learned end-to-end with the entire network. We

will present ablation studies showing that both the residual

connection and the 1×1 convolution contribute to the effec-

tiveness of the denoising block. The generic form of the

denoising block allows us to explore various denoising op-

erations, as introduced next.

4.2. Denoising Operations

We experiment with four different instantiations of the

denoising operation in our denoising blocks.

Non-local means. Non-local means [2] compute a de-

noised feature map y of an input feature map x by taking

a weighted mean of features in all spatial locations L:

yi =

1

C(x)

f (xi, xj) · xj,

(1)

∀j∈L

where f (xi, xj) is a feature-dependent weighting function

and C(x) is a normalization function. We note that the

weighted average in Eqn. (1) is over xj, rather than another

embedding of xj, unlike [23, 24] — denoising is directly

on the input feature x, and the correspondence between the

feature channels in y and x is kept. Following [24], we con-

sider two forms:

• Gaussian (softmax) sets f (xi, xj) = e

1√

d

ber of channels, and C =∀j∈L f (xi, xj). By notic-

θ(xi)Tφ(xj ),

where θ(x) and φ(x) are two embedded versions of

x (obtained by two 1×1 convolutions), d is the num-

ing that f /C is the softmax function, this version is

shown in [24] to be equivalent to the softmax-based,

self-attention computation of [23].

• Dot product sets f (xi, xj) = xT

i xj and C(x) = N,

where N is the number of pixels in x. Unlike the

Gaussian non-local means, the weights of the weighted

mean do not sum up to 1 in dot-product non-local

means. However, qualitative evaluations suggest it

does suppress noise in the features. Experiments also

show this version improves adversarial robustness. In-

terestingly, we find that it is unnecessary to embed x

in the dot-product version of non-local means for the

model to work well. This is unlike the Gaussian non-

local means, in which embedding is essential. The dot-

product version provides a denoising operation with no

extra parameters (blue box in Figure 5).

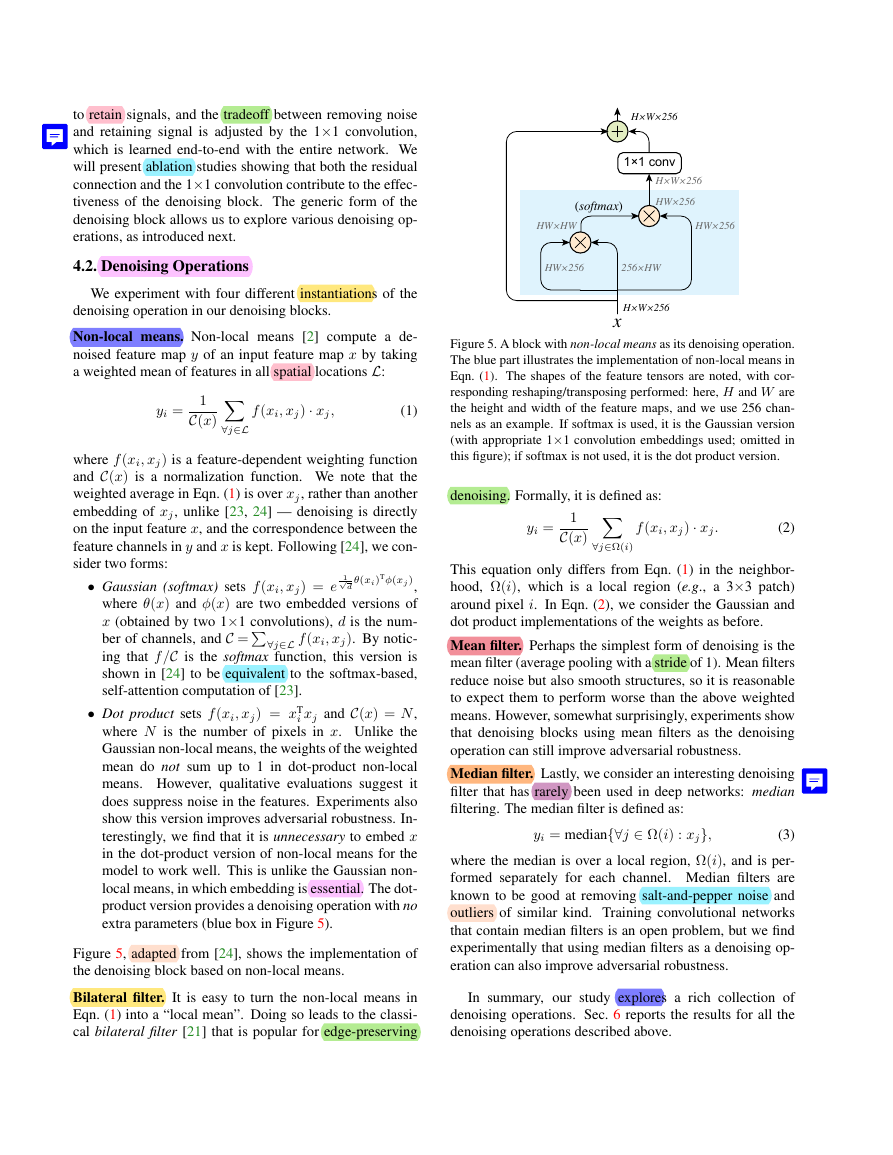

Figure 5, adapted from [24], shows the implementation of

the denoising block based on non-local means.

Bilateral filter. It is easy to turn the non-local means in

Eqn. (1) into a “local mean”. Doing so leads to the classi-

cal bilateral filter [21] that is popular for edge-preserving

Figure 5. A block with non-local means as its denoising operation.

The blue part illustrates the implementation of non-local means in

Eqn. (1). The shapes of the feature tensors are noted, with cor-

responding reshaping/transposing performed: here, H and W are

the height and width of the feature maps, and we use 256 chan-

nels as an example. If softmax is used, it is the Gaussian version

(with appropriate 1×1 convolution embeddings used; omitted in

this figure); if softmax is not used, it is the dot product version.

denoising. Formally, it is defined as:

∀j∈Ω(i)

yi =

1

C(x)

f (xi, xj) · xj.

(2)

This equation only differs from Eqn. (1) in the neighbor-

hood, Ω(i), which is a local region (e.g., a 3×3 patch)

around pixel i. In Eqn. (2), we consider the Gaussian and

dot product implementations of the weights as before.

Mean filter. Perhaps the simplest form of denoising is the

mean filter (average pooling with a stride of 1). Mean filters

reduce noise but also smooth structures, so it is reasonable

to expect them to perform worse than the above weighted

means. However, somewhat surprisingly, experiments show

that denoising blocks using mean filters as the denoising

operation can still improve adversarial robustness.

Median filter. Lastly, we consider an interesting denoising

filter that has rarely been used in deep networks: median

filtering. The median filter is defined as:

yi = median{∀j ∈ Ω(i) : xj},

(3)

where the median is over a local region, Ω(i), and is per-

formed separately for each channel. Median filters are

known to be good at removing salt-and-pepper noise and

outliers of similar kind. Training convolutional networks

that contain median filters is an open problem, but we find

experimentally that using median filters as a denoising op-

eration can also improve adversarial robustness.

In summary, our study explores a rich collection of

denoising operations. Sec. 6 reports the results for all the

denoising operations described above.

1×1 convH×W×256HW×256256×HWHW×HWHW×256HW×256H×W×256H×W×256x(softmax)�

5. Adversarial Training

6. Experiments

We show the effectiveness of feature denoising on top of

very strong baselines. Our strong experimental results are

partly driven by a successful implementation of adversarial

training [6, 16]. In this section, we describe our implemen-

tation of adversarial training, which is used for training both

baseline models and our feature denoising models.

The basic idea of adversarial training [6, 16] is to train

the network on adversarially perturbed images. The ad-

versarially perturbed images can be generated by a given

white-box attacker based on the current parameters of the

models. We use the Projected Gradient Descent (PGD)2

[16] as the white-box attacker for adversarial training.

PGD attacker. PGD is an iterative attacker. At each itera-

tion, it performs a gradient descent step in the loss function

w.r.t. the image pixel values, based on an adversarially se-

lected output target. Next, it projects the resulting perturbed

images into the feasible solution space — within a maxi-

mum per-pixel perturbation of � of the clean image (that is,

subject to an L∞ constraint). The hyper-parameters of the

PGD attacker during adversarial training are: the maximum

perturbation for each pixel � = 16, the attack step size α = 1,

and the number of attack iterations n = 30. For this PGD

in adversarial training, we can initialize the adversarial im-

age by the clean image, or randomly within the allowed �

[16]. We randomly choose from both initializations in the

PGD attacker during adversarial training: 20% of training

batches use clean images to initialize PGD, and 80% use

random points within the allowed �.

Distributed training with adversarial images. For each

mini-batch, we use PGD to generate adversarial images for

that mini-batch. Then we perform a one-step SGD on these

perturbed images and update the model weights. Our SGD

update is based exclusively on adversarial images; the mini-

batch contains no clean images.

Because a single SGD update is preceded by n-step

PGD (with n = 30), the total amount of computation in

adversarial training is ∼n× bigger than standard (clean)

training. To make adversarial training practical, we per-

form distributed training using synchronized SGD on 128

GPUs. Each mini-batch contains 32 images per GPU (i.e.,

the total mini-batch size is 128×32 = 4096). We follow the

training recipe of [7]3 to train models with such large mini-

batches. On ImageNet, our models are trained for a total of

110 epochs; we decrease the learning rate by 10× at the 35-

th, 70-th, and 95-th epoch. A label smoothing [19] of 0.1 is

used. The total time needed for adversarial training on 128

Nvidia V100 GPUs is approximately 38 hours for the base-

line ResNet-101 model, and approximately 52 hours for the

baseline ResNet-152 model.

2Publicly available: https://github.com/MadryLab/cifar10_challenge

3Implemented using the publicly available Tensorpack framework [25].

We evaluate feature denoising on the ImageNet classi-

fication dataset [18] that has ∼1.28 million images in 1000

classes. Following common protocols [1, 10] for adversarial

images on ImageNet, we consider targeted attacks when

evaluating under the white-box settings, where the targeted

class is selected uniformly at random; targeted attacks are

also used in our adversarial training. We evaluate top-1

classification accuracy on the 50k ImageNet validation im-

ages that are adversarially perturbed by the attacker (regard-

less of its targets), also following [1, 10].

In this paper, adversarial perturbation is considered un-

der L∞ norm (i.e., maximum difference for each pixel),

with an allowed maximum value of �. The value of � is

relative to the pixel intensity scale of 256.

Our baselines are ResNet-101/152 [9]. By default, we

add 4 denoising blocks to a ResNet: each is added after the

last residual block of res2, res3, res4, and res5, respectively.

6.1. Against White-box Attacks

Following the protocol of ALP [10], we report defense

results against PGD as the white-box attacker.4 We evaluate

with � =16, a challenging case for defenders on ImageNet.

Following [16], the PGD white-box attacker initializes

the adversarial perturbation from a random point within the

allowed � cube. We set its step size α = 1, except for 10-

iteration attacks where α is set to �/10 = 1.6. We consider a

numbers of PGD attack iterations ranging from 10 to 2000.

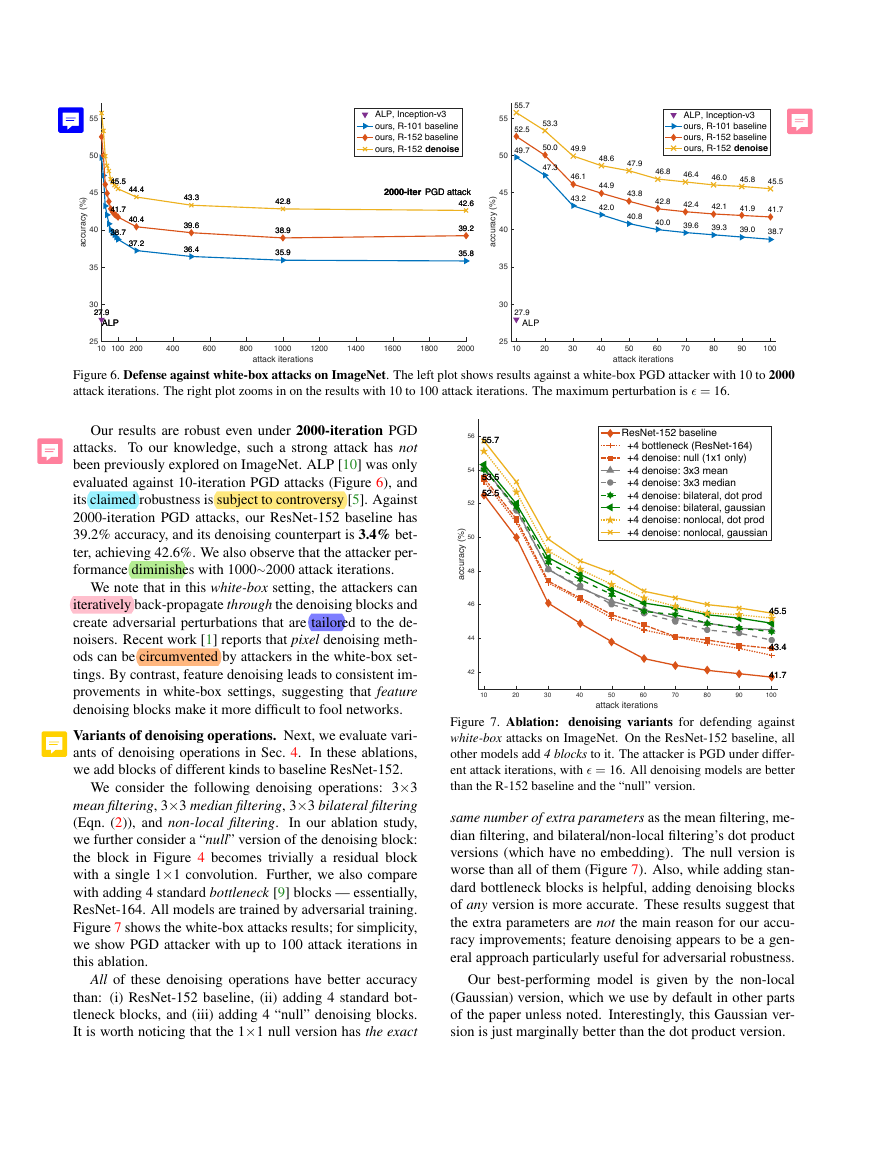

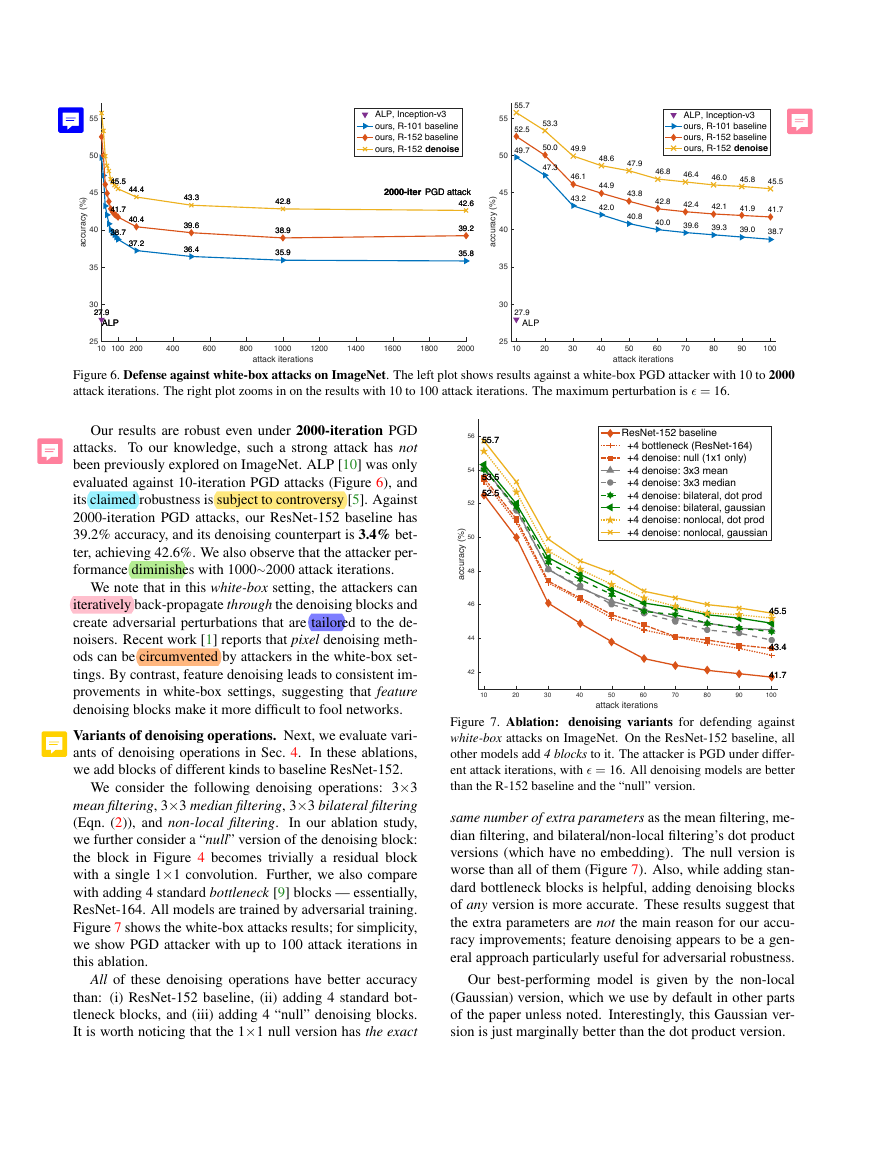

Main results. Figure 6 shows the main results. We first

compare with ALP [10], the previous state-of-the-art. ALP

was evaluated under 10-iteration PGD attack in [10], on

Inception-v3 [19]. It achieves 27.9% accuracy on ImageNet

validation images (Figure 6, purple triangle).

ResNet-101 and ResNet-152 in Figure 6 are our baseline

models (without any denoising blocks) trained using our

adversarial training implementation. Even with the lower-

capacity model of R-101, our baseline is very strong — it

has 49.7% accuracy under 10-iteration PGD attacks, con-

siderably better than the ALP result. This shows that our

adversarial training system is solid; we note that the com-

parison with ALP is on the system-level as they differ in

other aspects (backbone networks, implementations, etc.).

“R-152, denoise” in Figure 6 is our model of ResNet-152

with four denoising blocks added. Here we show the best-

performing version (non-local with Gaussian), which we

ablate next. There is a consistent performance improvement

introduced by the denoising blocks. Under the 10-iteration

PGD attack, it improves the accuracy of ResNet-152 base-

line by 3.2% from 52.5% to 55.7% (Figure 6, right).

4We have also evaluated other attackers, including FGSM [6], iterative

FGSM [12], and its momentum variant [3]. Similar to [10], we found that

PGD is the strongest white-box attacker among them.

�

Figure 6. Defense against white-box attacks on ImageNet. The left plot shows results against a white-box PGD attacker with 10 to 2000

attack iterations. The right plot zooms in on the results with 10 to 100 attack iterations. The maximum perturbation is � = 16.

Our results are robust even under 2000-iteration PGD

attacks. To our knowledge, such a strong attack has not

been previously explored on ImageNet. ALP [10] was only

evaluated against 10-iteration PGD attacks (Figure 6), and

its claimed robustness is subject to controversy [5]. Against

2000-iteration PGD attacks, our ResNet-152 baseline has

39.2% accuracy, and its denoising counterpart is 3.4% bet-

ter, achieving 42.6%. We also observe that the attacker per-

formance diminishes with 1000∼2000 attack iterations.

We note that in this white-box setting, the attackers can

iteratively back-propagate through the denoising blocks and

create adversarial perturbations that are tailored to the de-

noisers. Recent work [1] reports that pixel denoising meth-

ods can be circumvented by attackers in the white-box set-

tings. By contrast, feature denoising leads to consistent im-

provements in white-box settings, suggesting that feature

denoising blocks make it more difficult to fool networks.

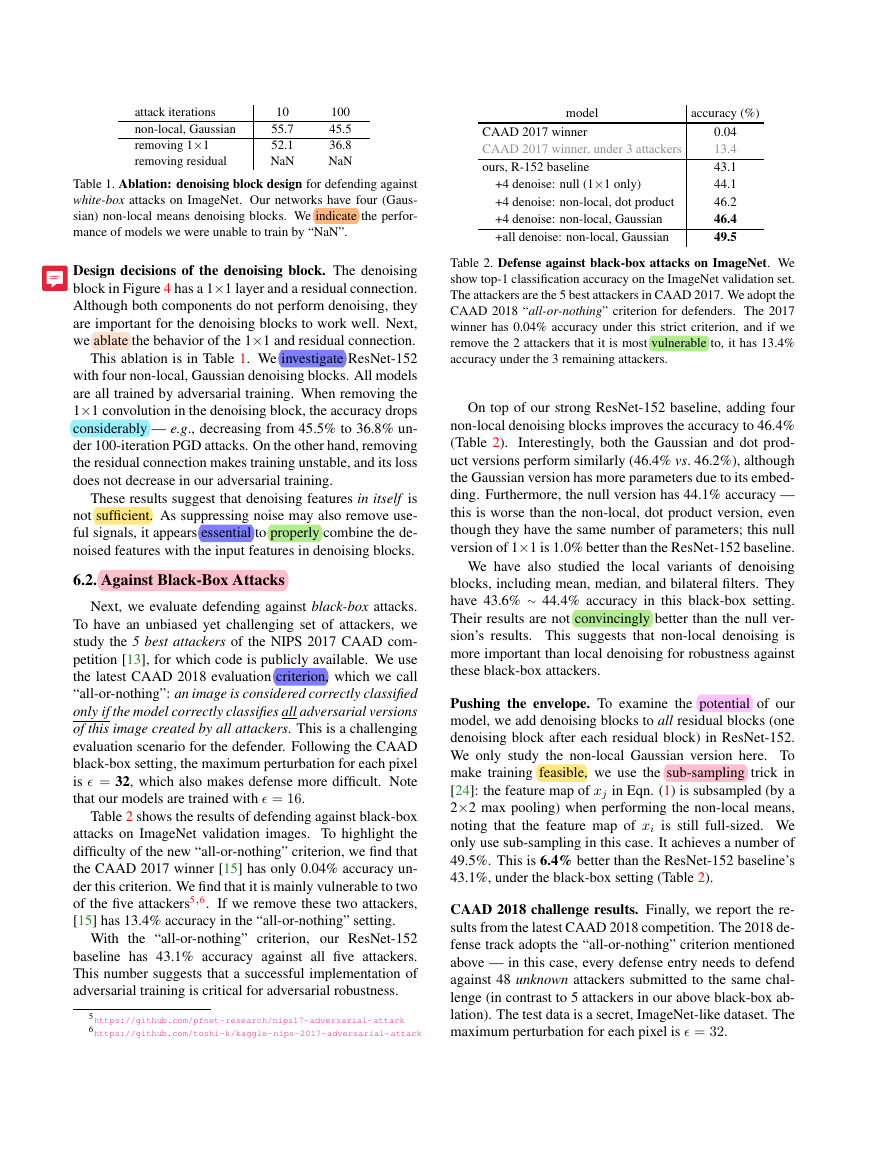

Variants of denoising operations. Next, we evaluate vari-

ants of denoising operations in Sec. 4. In these ablations,

we add blocks of different kinds to baseline ResNet-152.

We consider the following denoising operations: 3×3

mean filtering, 3×3 median filtering, 3×3 bilateral filtering

(Eqn. (2)), and non-local filtering.

In our ablation study,

we further consider a “null” version of the denoising block:

the block in Figure 4 becomes trivially a residual block

with a single 1×1 convolution. Further, we also compare

with adding 4 standard bottleneck [9] blocks — essentially,

ResNet-164. All models are trained by adversarial training.

Figure 7 shows the white-box attacks results; for simplicity,

we show PGD attacker with up to 100 attack iterations in

this ablation.

All of these denoising operations have better accuracy

than: (i) ResNet-152 baseline, (ii) adding 4 standard bot-

tleneck blocks, and (iii) adding 4 “null” denoising blocks.

It is worth noticing that the 1×1 null version has the exact

Figure 7. Ablation: denoising variants for defending against

white-box attacks on ImageNet. On the ResNet-152 baseline, all

other models add 4 blocks to it. The attacker is PGD under differ-

ent attack iterations, with � = 16. All denoising models are better

than the R-152 baseline and the “null” version.

same number of extra parameters as the mean filtering, me-

dian filtering, and bilateral/non-local filtering’s dot product

versions (which have no embedding). The null version is

worse than all of them (Figure 7). Also, while adding stan-

dard bottleneck blocks is helpful, adding denoising blocks

of any version is more accurate. These results suggest that

the extra parameters are not the main reason for our accu-

racy improvements; feature denoising appears to be a gen-

eral approach particularly useful for adversarial robustness.

Our best-performing model is given by the non-local

(Gaussian) version, which we use by default in other parts

of the paper unless noted. Interestingly, this Gaussian ver-

sion is just marginally better than the dot product version.

10100200400600800100012001400160018002000attack iterations25303540455055accuracy (%)ALP45.544.443.342.842.641.740.439.638.939.238.737.236.435.935.827.92000-iter PGD attackALP45.544.443.342.842.641.740.439.638.939.238.737.236.435.935.827.92000-iter PGD attackALP, Inception-v3ours, R-101 baselineours, R-152 baselineours, R-152 denoise102030405060708090100attack iterations25303540455055accuracy (%)ALP55.753.349.948.647.946.846.446.045.845.552.550.046.144.943.842.842.442.141.941.749.747.343.242.040.840.039.639.339.038.727.9ALP, Inception-v3ours, R-101 baselineours, R-152 baselineours, R-152 denoise102030405060708090100attack iterations4244464850525456accuracy (%)55.745.553.543.452.541.755.745.553.543.452.541.7ResNet-152 baseline +4 bottleneck (ResNet-164) +4 denoise: null (1x1 only) +4 denoise: 3x3 mean +4 denoise: 3x3 median +4 denoise: bilateral, dot prod +4 denoise: bilateral, gaussian +4 denoise: nonlocal, dot prod +4 denoise: nonlocal, gaussian�

attack iterations

non-local, Gaussian

removing 1×1

removing residual

10

55.7

52.1

NaN

100

45.5

36.8

NaN

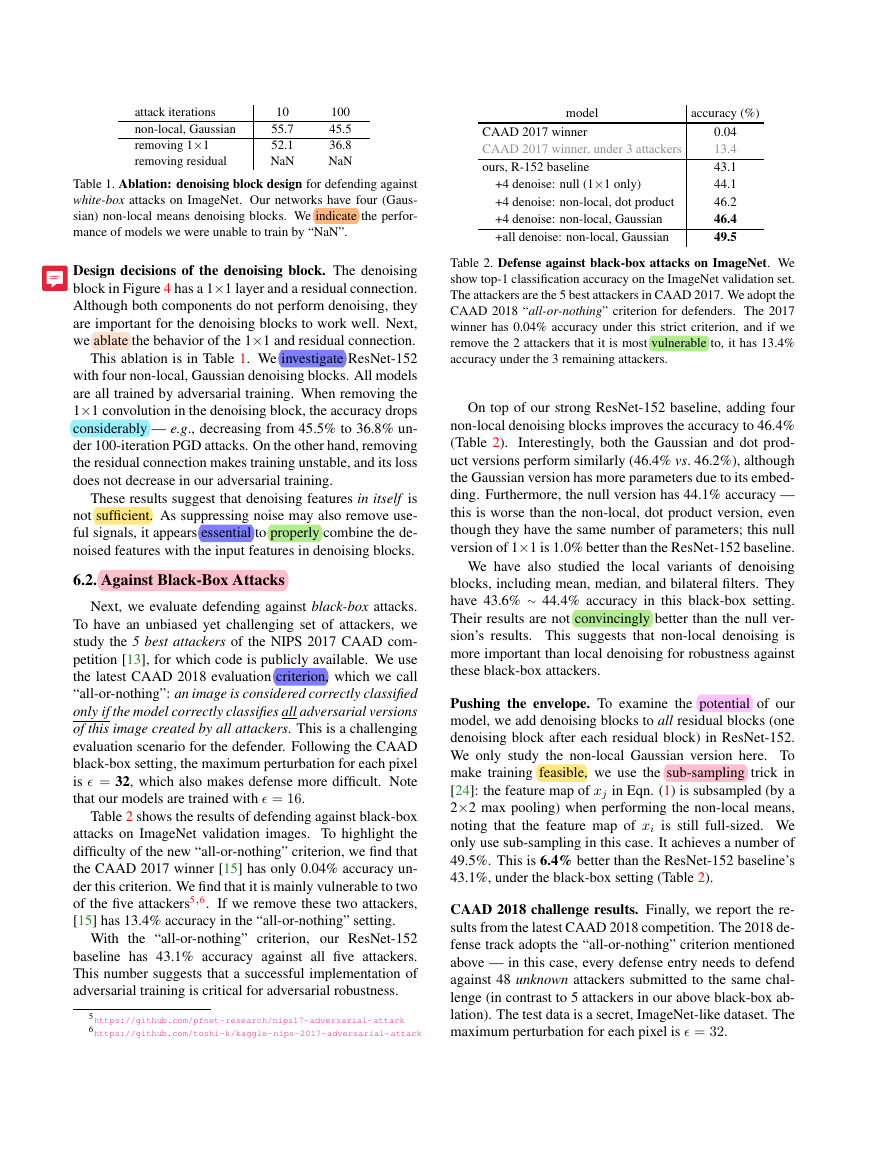

Table 1. Ablation: denoising block design for defending against

white-box attacks on ImageNet. Our networks have four (Gaus-

sian) non-local means denoising blocks. We indicate the perfor-

mance of models we were unable to train by “NaN”.

Design decisions of the denoising block. The denoising

block in Figure 4 has a 1×1 layer and a residual connection.

Although both components do not perform denoising, they

are important for the denoising blocks to work well. Next,

we ablate the behavior of the 1×1 and residual connection.

This ablation is in Table 1. We investigate ResNet-152

with four non-local, Gaussian denoising blocks. All models

are all trained by adversarial training. When removing the

1×1 convolution in the denoising block, the accuracy drops

considerably — e.g., decreasing from 45.5% to 36.8% un-

der 100-iteration PGD attacks. On the other hand, removing

the residual connection makes training unstable, and its loss

does not decrease in our adversarial training.

These results suggest that denoising features in itself is

not sufficient. As suppressing noise may also remove use-

ful signals, it appears essential to properly combine the de-

noised features with the input features in denoising blocks.

6.2. Against Black-Box Attacks

Next, we evaluate defending against black-box attacks.

To have an unbiased yet challenging set of attackers, we

study the 5 best attackers of the NIPS 2017 CAAD com-

petition [13], for which code is publicly available. We use

the latest CAAD 2018 evaluation criterion, which we call

“all-or-nothing”: an image is considered correctly classified

only if the model correctly classifies all adversarial versions

of this image created by all attackers. This is a challenging

evaluation scenario for the defender. Following the CAAD

black-box setting, the maximum perturbation for each pixel

is � = 32, which also makes defense more difficult. Note

that our models are trained with � = 16.

Table 2 shows the results of defending against black-box

attacks on ImageNet validation images. To highlight the

difficulty of the new “all-or-nothing” criterion, we find that

the CAAD 2017 winner [15] has only 0.04% accuracy un-

der this criterion. We find that it is mainly vulnerable to two

of the five attackers5,6. If we remove these two attackers,

[15] has 13.4% accuracy in the “all-or-nothing” setting.

With the “all-or-nothing” criterion, our ResNet-152

baseline has 43.1% accuracy against all five attackers.

This number suggests that a successful implementation of

adversarial training is critical for adversarial robustness.

5https://github.com/pfnet-research/nips17-adversarial-attack

6https://github.com/toshi-k/kaggle-nips-2017-adversarial-attack

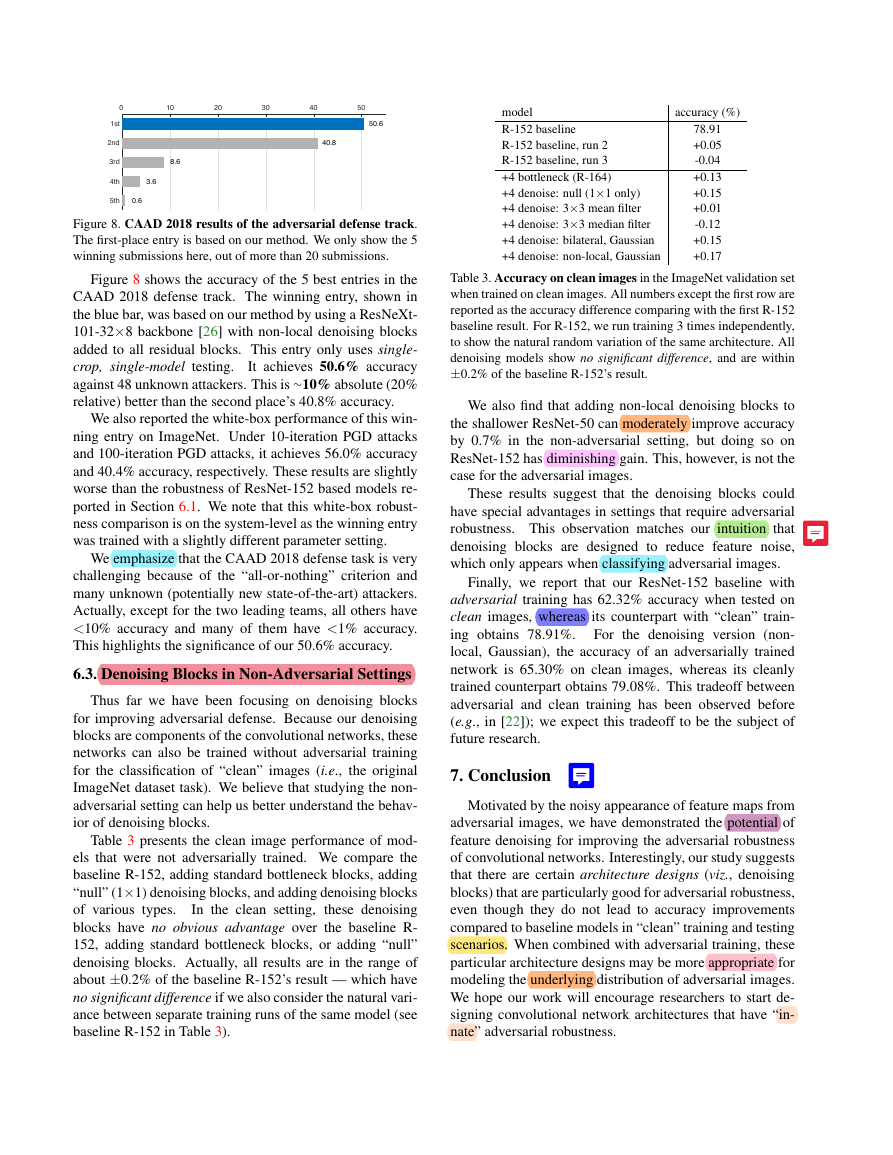

model

accuracy (%)

CAAD 2017 winner

CAAD 2017 winner, under 3 attackers

ours, R-152 baseline

+4 denoise: null (1×1 only)

+4 denoise: non-local, dot product

+4 denoise: non-local, Gaussian

+all denoise: non-local, Gaussian

0.04

13.4

43.1

44.1

46.2

46.4

49.5

Table 2. Defense against black-box attacks on ImageNet. We

show top-1 classification accuracy on the ImageNet validation set.

The attackers are the 5 best attackers in CAAD 2017. We adopt the

CAAD 2018 “all-or-nothing” criterion for defenders. The 2017

winner has 0.04% accuracy under this strict criterion, and if we

remove the 2 attackers that it is most vulnerable to, it has 13.4%

accuracy under the 3 remaining attackers.

On top of our strong ResNet-152 baseline, adding four

non-local denoising blocks improves the accuracy to 46.4%

(Table 2).

Interestingly, both the Gaussian and dot prod-

uct versions perform similarly (46.4% vs. 46.2%), although

the Gaussian version has more parameters due to its embed-

ding. Furthermore, the null version has 44.1% accuracy —

this is worse than the non-local, dot product version, even

though they have the same number of parameters; this null

version of 1×1 is 1.0% better than the ResNet-152 baseline.

We have also studied the local variants of denoising

blocks, including mean, median, and bilateral filters. They

have 43.6% ∼ 44.4% accuracy in this black-box setting.

Their results are not convincingly better than the null ver-

sion’s results. This suggests that non-local denoising is

more important than local denoising for robustness against

these black-box attackers.

Pushing the envelope. To examine the potential of our

model, we add denoising blocks to all residual blocks (one

denoising block after each residual block) in ResNet-152.

We only study the non-local Gaussian version here. To

make training feasible, we use the sub-sampling trick in

[24]: the feature map of xj in Eqn. (1) is subsampled (by a

2×2 max pooling) when performing the non-local means,

noting that the feature map of xi is still full-sized. We

only use sub-sampling in this case. It achieves a number of

49.5%. This is 6.4% better than the ResNet-152 baseline’s

43.1%, under the black-box setting (Table 2).

CAAD 2018 challenge results. Finally, we report the re-

sults from the latest CAAD 2018 competition. The 2018 de-

fense track adopts the “all-or-nothing” criterion mentioned

above — in this case, every defense entry needs to defend

against 48 unknown attackers submitted to the same chal-

lenge (in contrast to 5 attackers in our above black-box ab-

lation). The test data is a secret, ImageNet-like dataset. The

maximum perturbation for each pixel is � = 32.

�

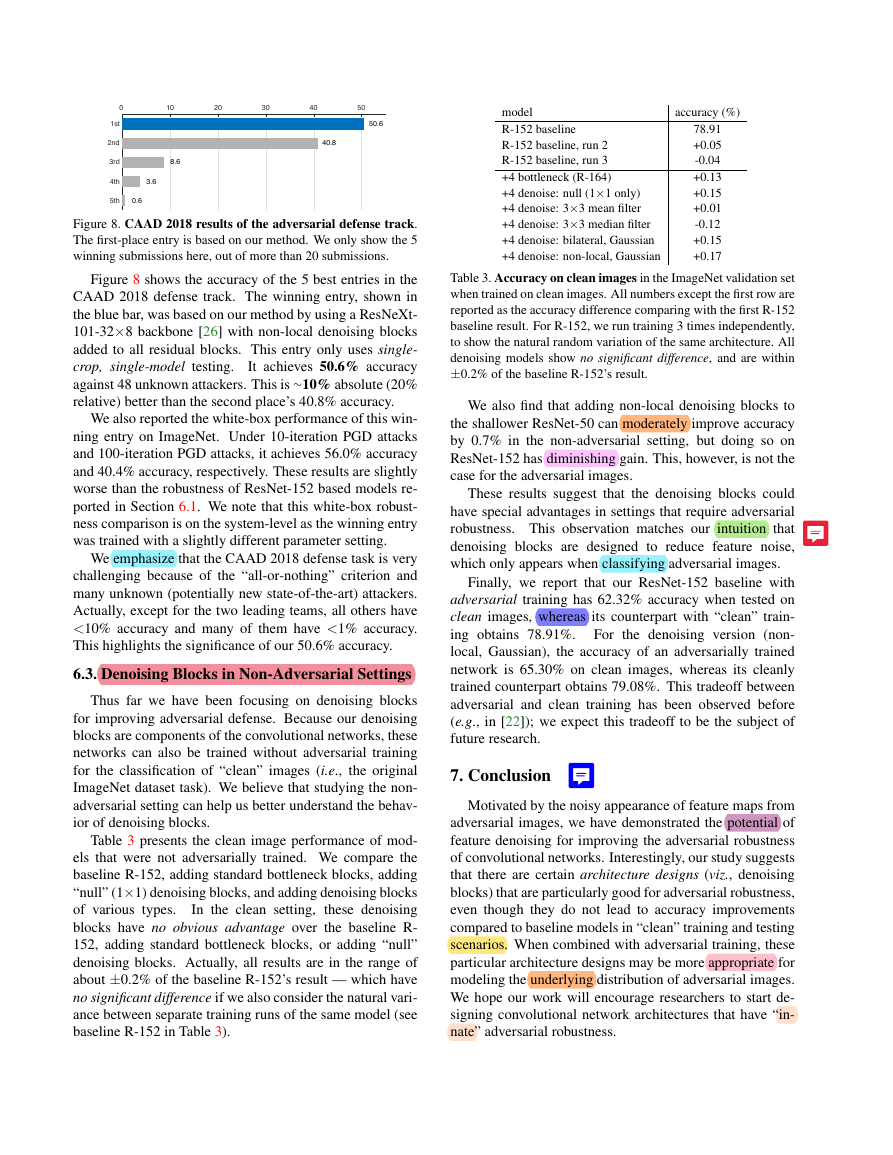

Figure 8. CAAD 2018 results of the adversarial defense track.

The first-place entry is based on our method. We only show the 5

winning submissions here, out of more than 20 submissions.

Figure 8 shows the accuracy of the 5 best entries in the

CAAD 2018 defense track. The winning entry, shown in

the blue bar, was based on our method by using a ResNeXt-

101-32×8 backbone [26] with non-local denoising blocks

added to all residual blocks. This entry only uses single-

It achieves 50.6% accuracy

crop, single-model testing.

against 48 unknown attackers. This is ∼10% absolute (20%

relative) better than the second place’s 40.8% accuracy.

We also reported the white-box performance of this win-

ning entry on ImageNet. Under 10-iteration PGD attacks

and 100-iteration PGD attacks, it achieves 56.0% accuracy

and 40.4% accuracy, respectively. These results are slightly

worse than the robustness of ResNet-152 based models re-

ported in Section 6.1. We note that this white-box robust-

ness comparison is on the system-level as the winning entry

was trained with a slightly different parameter setting.

We emphasize that the CAAD 2018 defense task is very

challenging because of the “all-or-nothing” criterion and

many unknown (potentially new state-of-the-art) attackers.

Actually, except for the two leading teams, all others have

<10% accuracy and many of them have <1% accuracy.

This highlights the significance of our 50.6% accuracy.

6.3. Denoising Blocks in Non-Adversarial Settings

Thus far we have been focusing on denoising blocks

for improving adversarial defense. Because our denoising

blocks are components of the convolutional networks, these

networks can also be trained without adversarial training

for the classification of “clean” images (i.e., the original

ImageNet dataset task). We believe that studying the non-

adversarial setting can help us better understand the behav-

ior of denoising blocks.

In the clean setting,

Table 3 presents the clean image performance of mod-

els that were not adversarially trained. We compare the

baseline R-152, adding standard bottleneck blocks, adding

“null” (1×1) denoising blocks, and adding denoising blocks

of various types.

these denoising

blocks have no obvious advantage over the baseline R-

152, adding standard bottleneck blocks, or adding “null”

denoising blocks. Actually, all results are in the range of

about ±0.2% of the baseline R-152’s result — which have

no significant difference if we also consider the natural vari-

ance between separate training runs of the same model (see

baseline R-152 in Table 3).

model

R-152 baseline

R-152 baseline, run 2

R-152 baseline, run 3

+4 bottleneck (R-164)

+4 denoise: null (1×1 only)

+4 denoise: 3×3 mean filter

+4 denoise: 3×3 median filter

+4 denoise: bilateral, Gaussian

+4 denoise: non-local, Gaussian

accuracy (%)

78.91

+0.05

-0.04

+0.13

+0.15

+0.01

-0.12

+0.15

+0.17

Table 3. Accuracy on clean images in the ImageNet validation set

when trained on clean images. All numbers except the first row are

reported as the accuracy difference comparing with the first R-152

baseline result. For R-152, we run training 3 times independently,

to show the natural random variation of the same architecture. All

denoising models show no significant difference, and are within

±0.2% of the baseline R-152’s result.

We also find that adding non-local denoising blocks to

the shallower ResNet-50 can moderately improve accuracy

by 0.7% in the non-adversarial setting, but doing so on

ResNet-152 has diminishing gain. This, however, is not the

case for the adversarial images.

These results suggest that the denoising blocks could

have special advantages in settings that require adversarial

robustness. This observation matches our intuition that

denoising blocks are designed to reduce feature noise,

which only appears when classifying adversarial images.

Finally, we report that our ResNet-152 baseline with

adversarial training has 62.32% accuracy when tested on

clean images, whereas its counterpart with “clean” train-

ing obtains 78.91%.

For the denoising version (non-

local, Gaussian), the accuracy of an adversarially trained

network is 65.30% on clean images, whereas its cleanly

trained counterpart obtains 79.08%. This tradeoff between

adversarial and clean training has been observed before

(e.g., in [22]); we expect this tradeoff to be the subject of

future research.

7. Conclusion

Motivated by the noisy appearance of feature maps from

adversarial images, we have demonstrated the potential of

feature denoising for improving the adversarial robustness

of convolutional networks. Interestingly, our study suggests

that there are certain architecture designs (viz., denoising

blocks) that are particularly good for adversarial robustness,

even though they do not lead to accuracy improvements

compared to baseline models in “clean” training and testing

scenarios. When combined with adversarial training, these

particular architecture designs may be more appropriate for

modeling the underlying distribution of adversarial images.

We hope our work will encourage researchers to start de-

signing convolutional network architectures that have “in-

nate” adversarial robustness.

0 10203040501st2nd3rd4th5th50.640.8 8.6 3.6 0.6�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc