History of HCI

Key systems, people and ideas

Matthias Rauterberg

Technical University Eindhoven (TU/e)

The Netherlands

�

History of Computer Technology

Digital computer grounded in ideas from

1700’s & 1800’s

Computer technology became available in

the 1940’s and 1950’s

see further: History of Computing

History of HCI

© M. Rauterberg, TU/e

2

�

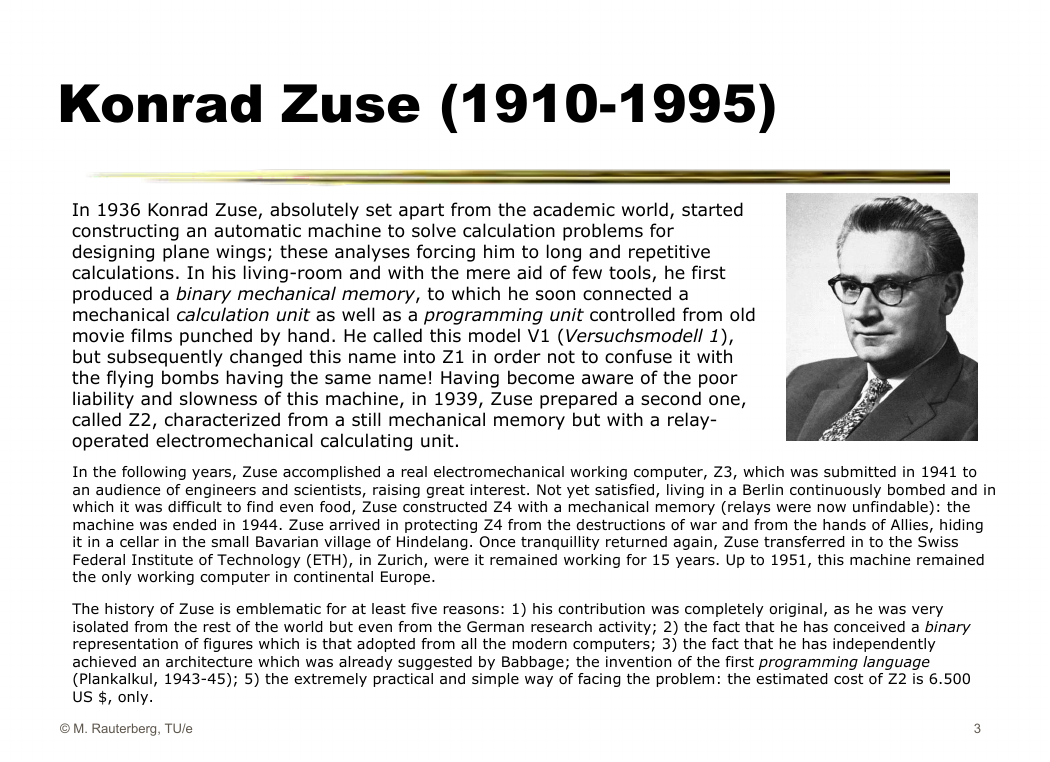

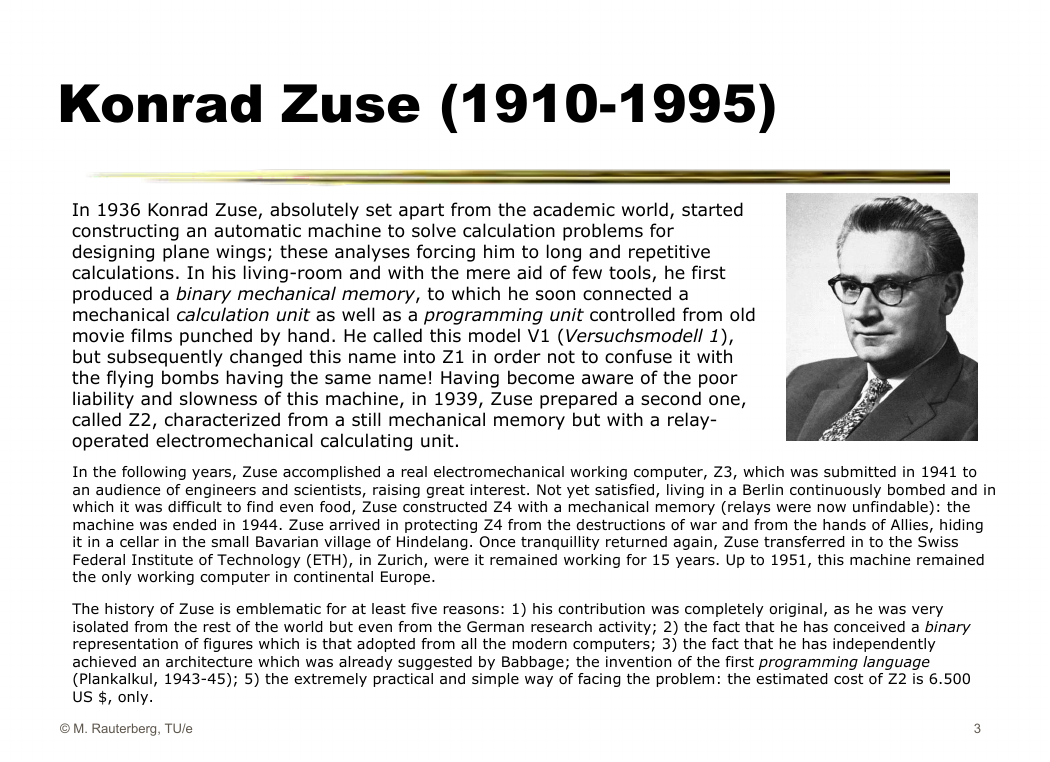

Konrad Zuse (1910-1995)

In 1936 Konrad Zuse, absolutely set apart from the academic world, started

constructing an automatic machine to solve calculation problems for

designing plane wings; these analyses forcing him to long and repetitive

calculations. In his living-room and with the mere aid of few tools, he first

produced a binary mechanical memory, to which he soon connected a

mechanical calculation unit as well as a programming unit controlled from old

movie films punched by hand. He called this model V1 (Versuchsmodell 1),

but subsequently changed this name into Z1 in order not to confuse it with

the flying bombs having the same name! Having become aware of the poor

liability and slowness of this machine, in 1939, Zuse prepared a second one,

called Z2, characterized from a still mechanical memory but with a relay-

operated electromechanical calculating unit.

In the following years, Zuse accomplished a real electromechanical working computer, Z3, which was submitted in 1941 to

an audience of engineers and scientists, raising great interest. Not yet satisfied, living in a Berlin continuously bombed and in

which it was difficult to find even food, Zuse constructed Z4 with a mechanical memory (relays were now unfindable): the

machine was ended in 1944. Zuse arrived in protecting Z4 from the destructions of war and from the hands of Allies, hiding

it in a cellar in the small Bavarian village of Hindelang. Once tranquillity returned again, Zuse transferred in to the Swiss

Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), in Zurich, were it remained working for 15 years. Up to 1951, this machine remained

the only working computer in continental Europe.

The history of Zuse is emblematic for at least five reasons: 1) his contribution was completely original, as he was very

isolated from the rest of the world but even from the German research activity; 2) the fact that he has conceived a binary

representation of figures which is that adopted from all the modern computers; 3) the fact that he has independently

achieved an architecture which was already suggested by Babbage; the invention of the first programming language

(Plankalkul, 1943-45); 5) the extremely practical and simple way of facing the problem: the estimated cost of Z2 is 6.500

US $, only.

© M. Rauterberg, TU/e

3

�

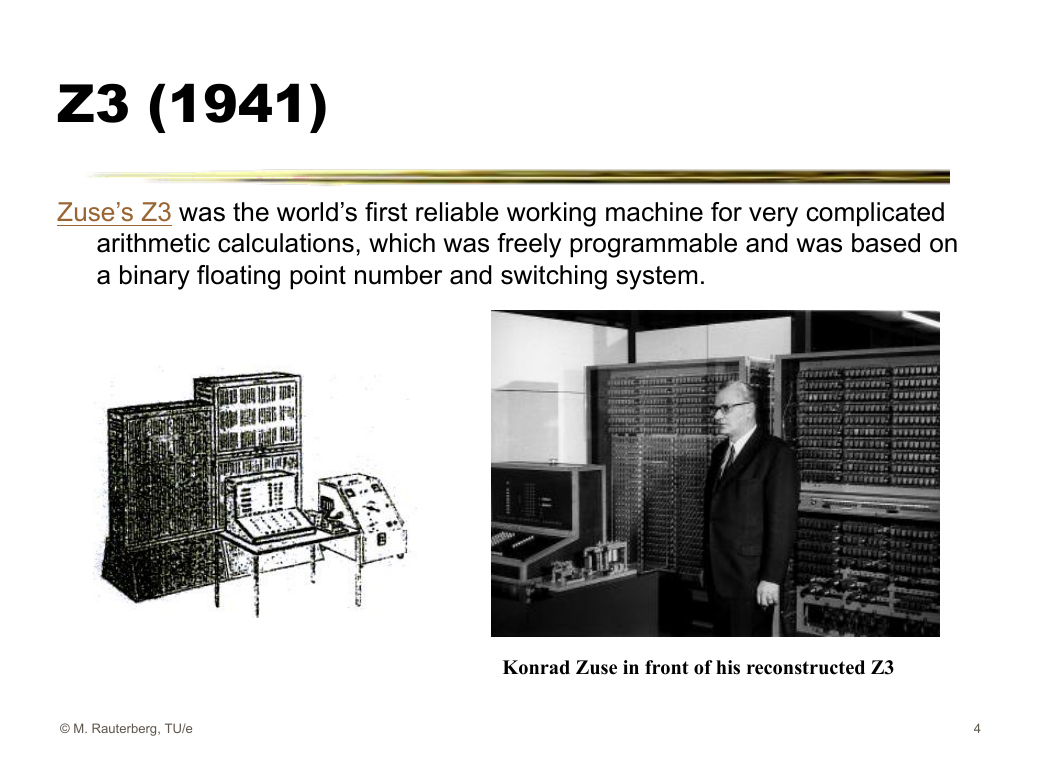

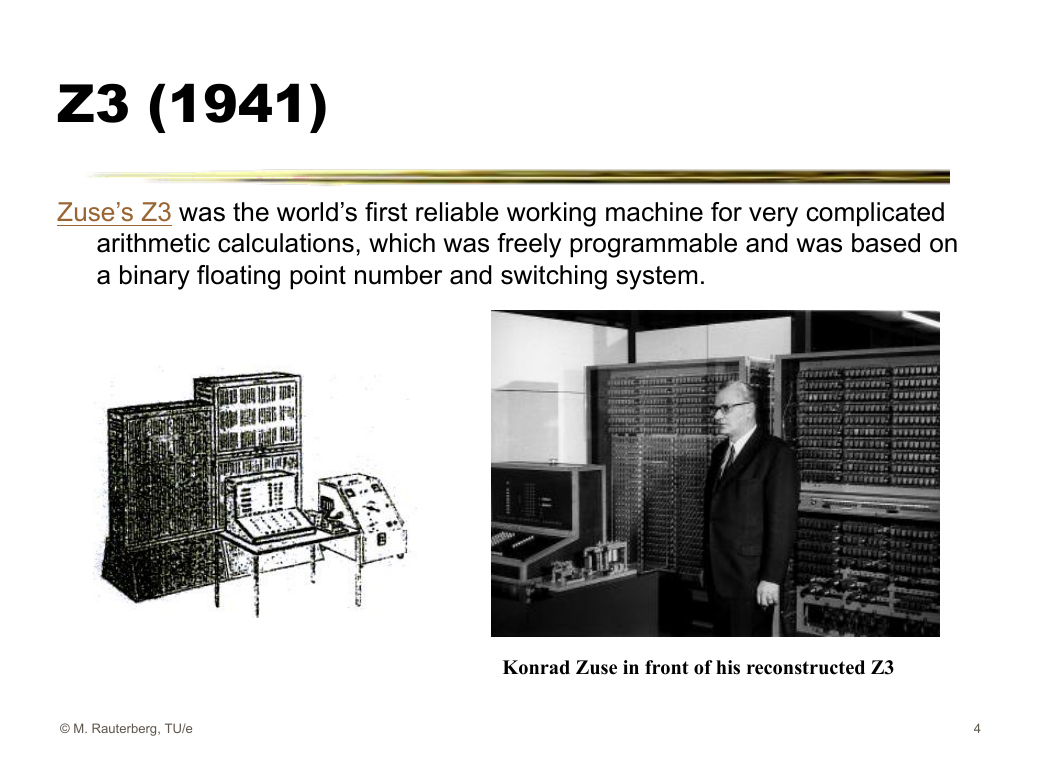

Z3 (1941)

Zuse’s Z3 was the world’s first reliable working machine for very complicated

arithmetic calculations, which was freely programmable and was based on

a binary floating point number and switching system.

© M. Rauterberg, TU/e

4

Konrad Zuse in front of his reconstructed Z3

�

Eniac (1943)

– A general view of the ENIAC, the first all electronic numerical integrator

and computer in USA.

© M. Rauterberg, TU/e

From IBM Archives.

5

�

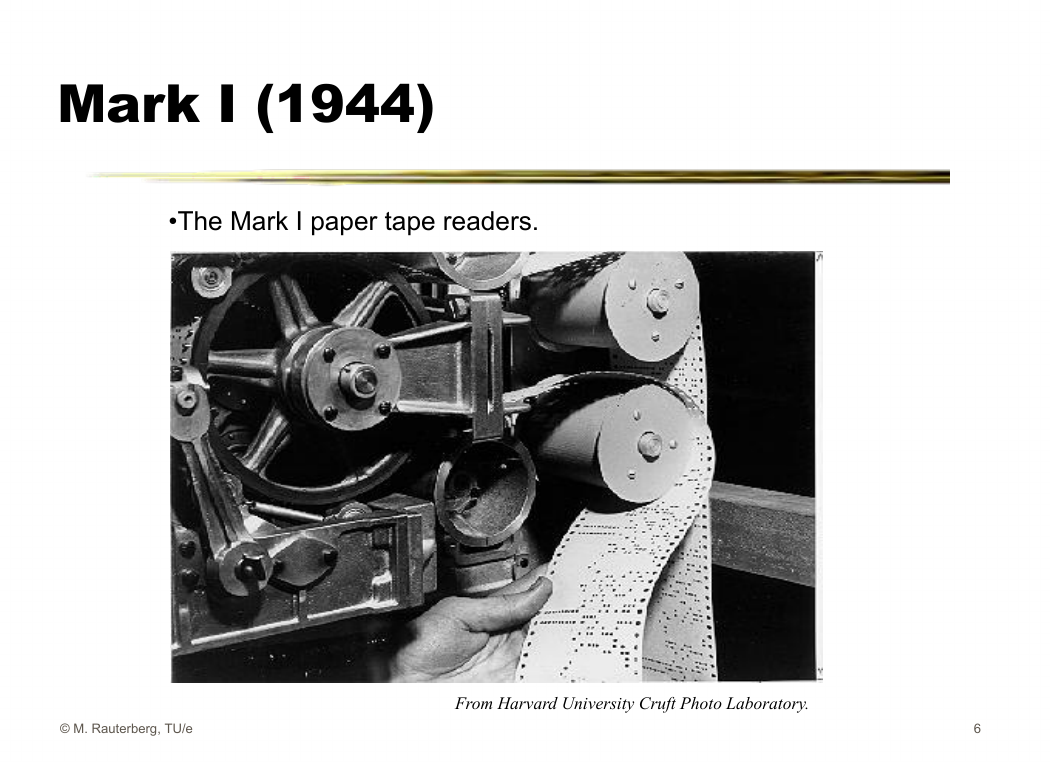

Mark I (1944)

•The Mark I paper tape readers.

© M. Rauterberg, TU/e

6

From Harvard University Cruft Photo Laboratory.

�

von Neuman Architecture (1946)

Instructions and data are stored in the same memory

for which there is a single link (the von Neumann

bottleneck) to the CPU which decodes and executes

instructions.

The CPU can have multiple functional units.

The memory access can be enhanced by use of caches

made from faster memory to allow greater bandwidth

and lower latency.

Johann (John) von Neumann

(1903-1957)

J. Presper Eckert Jr. and John Mauchly were the first to develop the von Neuman architecture. John von Neumann

wrote "First Draft of a Report to the EDVAC" describing the ideas of a stored memory computer. The complicated

story is described in the wonder history of computers "Engines of the Mind" by Joel Shurkin.

© M. Rauterberg, TU/e

7

�

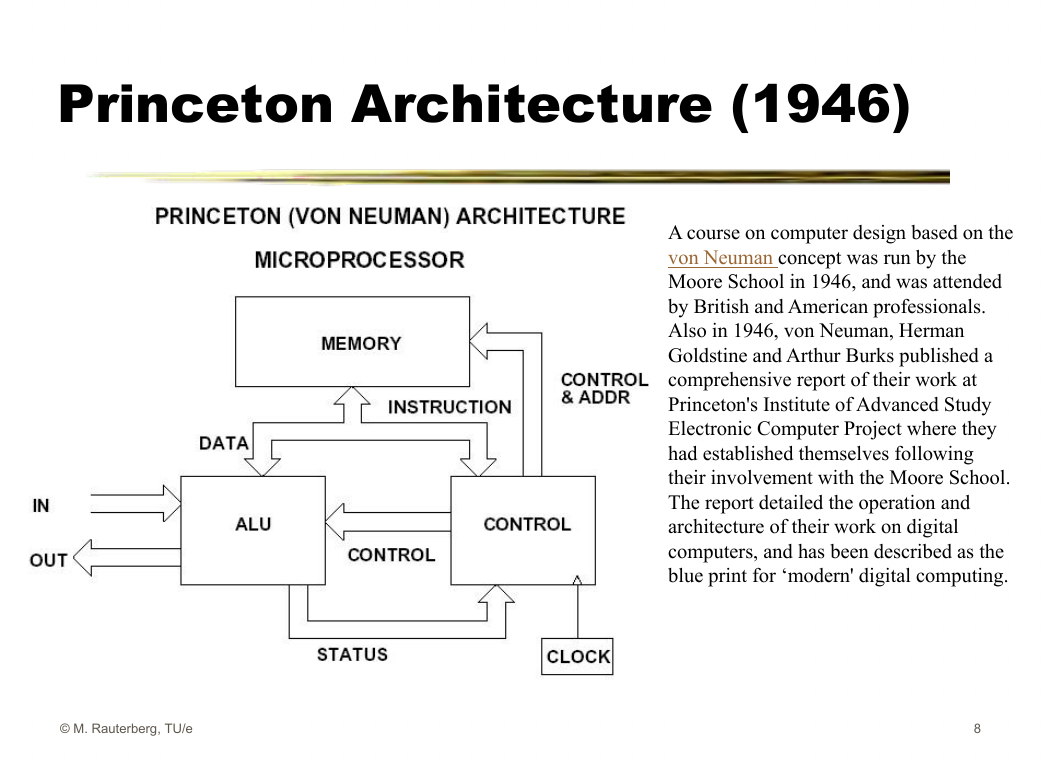

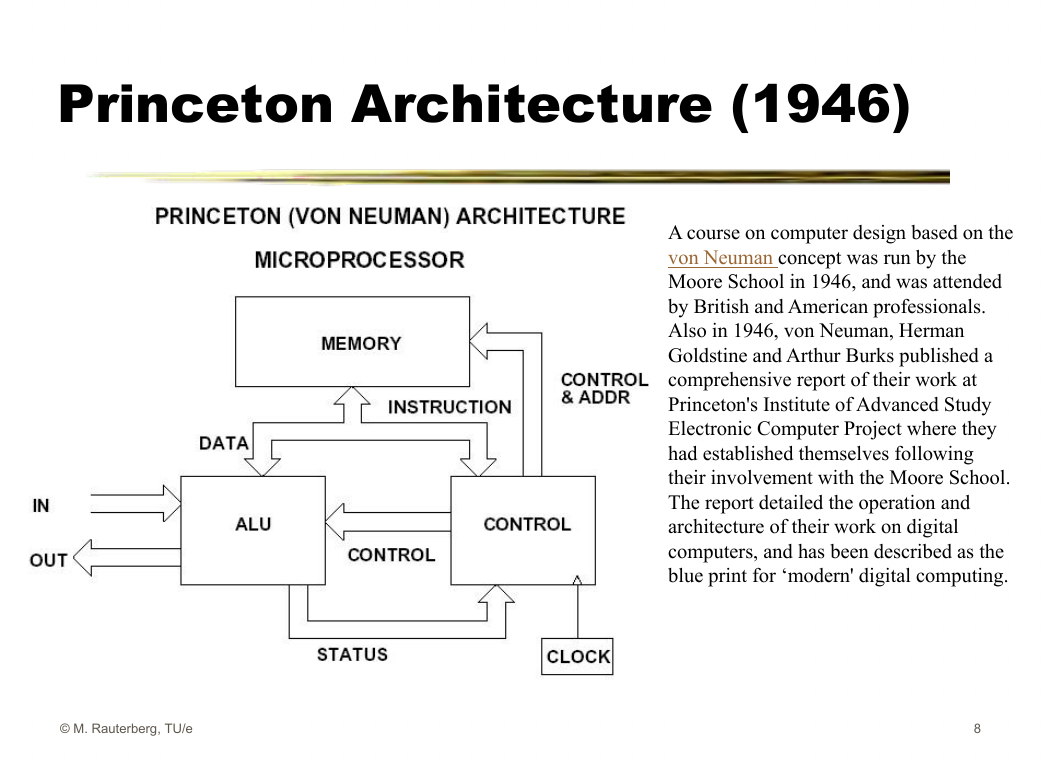

Princeton Architecture (1946)

A course on computer design based on the

von Neuman concept was run by the

Moore School in 1946, and was attended

by British and American professionals.

Also in 1946, von Neuman, Herman

Goldstine and Arthur Burks published a

comprehensive report of their work at

Princeton's Institute of Advanced Study

Electronic Computer Project where they

had established themselves following

their involvement with the Moore School.

The report detailed the operation and

architecture of their work on digital

computers, and has been described as the

blue print for ‘modern' digital computing.

© M. Rauterberg, TU/e

8

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc