Pro Django

Contents at a Glance

Contents

About the Author

About the Technical Reviewers

Acknowledgments

Preface

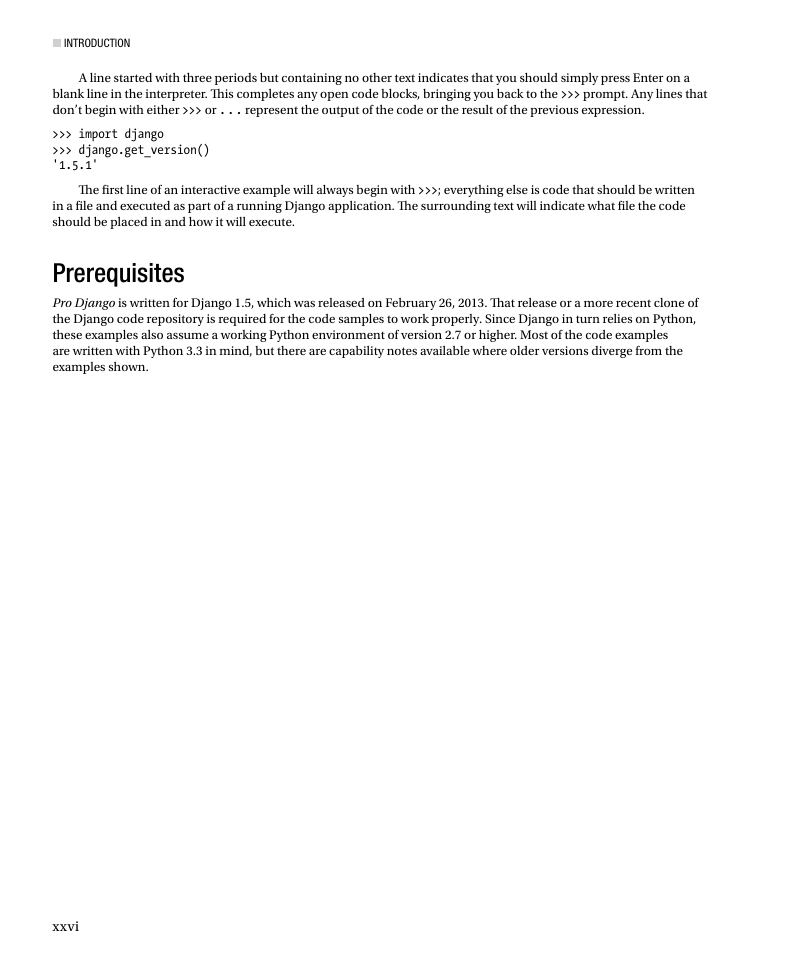

Introduction

Chapter 1: Understanding Django

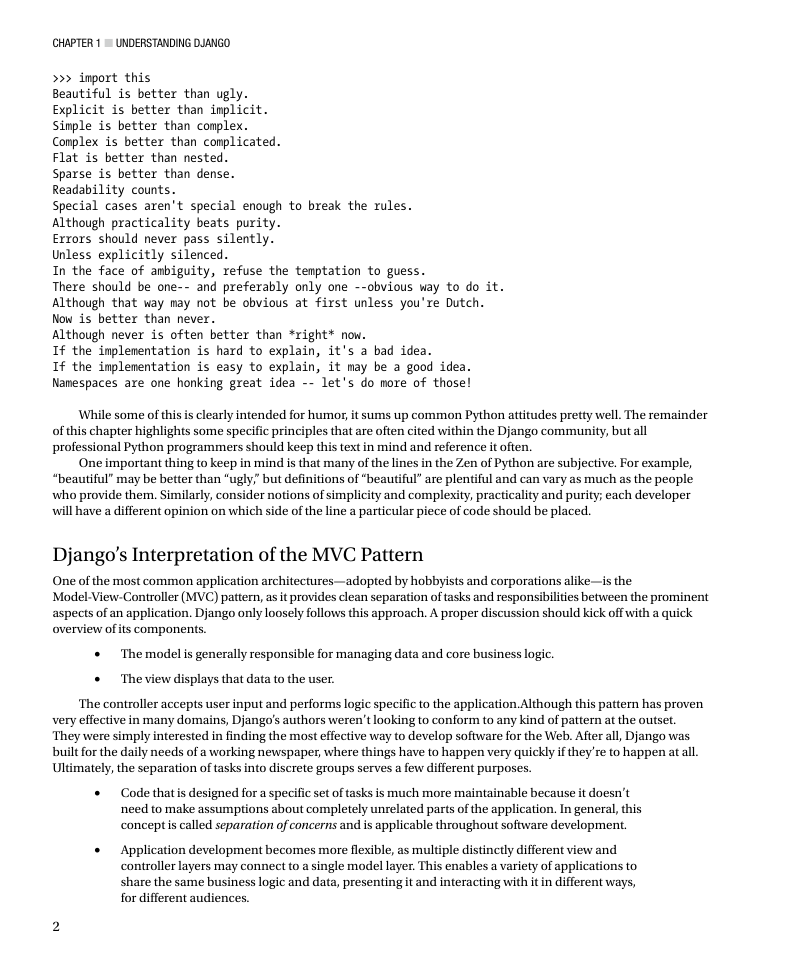

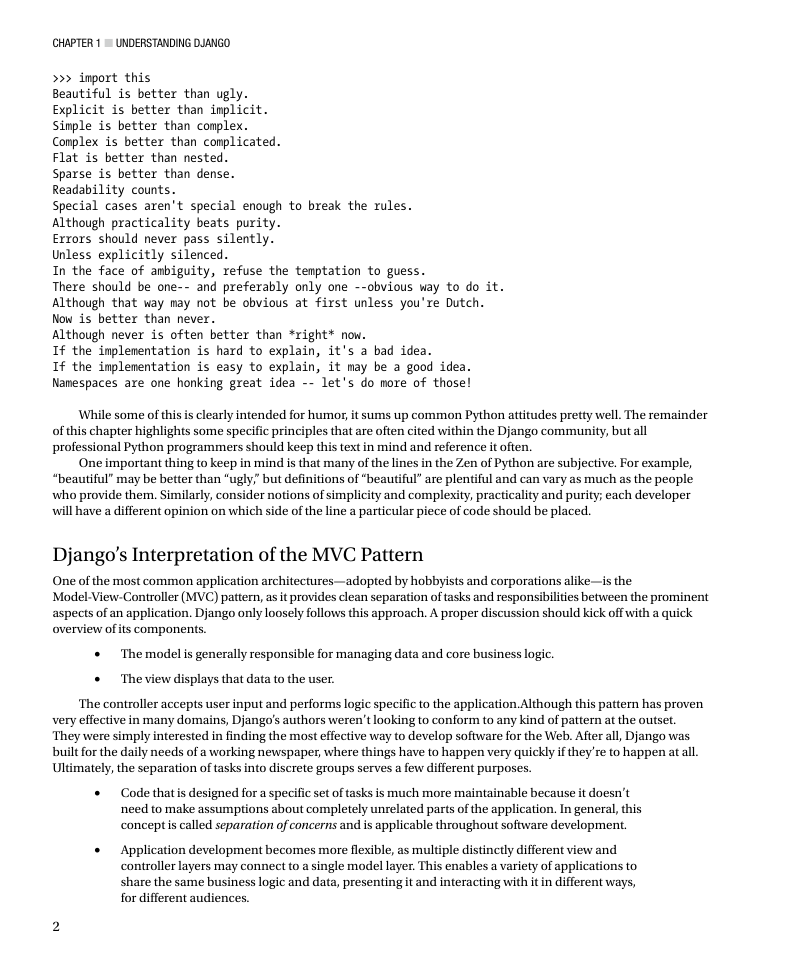

Philosophy

Django’s Interpretation of the MVC Pattern

Model

Template

URL Configuration

Loose Coupling

Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY)

A Focus on Readability

Failing Loudly

Documenting Rules

Community

Management of the Framework

News and Resources

Reusable Applications

Getting Help

Read the Documentation

Check Your Version

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Mailing Lists

Internet Relay Chat (IRC)

Now What?

Chapter 2: Django Is Python

How Python Builds Classes

Building a Class Programmatically

Metaclasses Change It Up

Using a Base Class with a Metaclass

Declarative Syntax

Centralized Access

The Base Class

Attribute Classes

Ordering Class Attributes

Class Declaration

Common Duck Typing Protocols

Callables

__call__(self[, …])

Dictionaries

__contains__(self, key)

__getitem__(self, key)

__setitem__(self, key, value)

Files

read(self, [size])

write(self, str)

close(self)

Iterables

__iter__(self)

Iterators

next(self)

Generators

Sequences

__len__(self)

__getitem__(self) and __setitem__(self, value)

Augmenting Functions

Excess Arguments

Positional Arguments

Keyword Arguments

Mixing Argument Types

Passing Argument Collections

Decorators

Decorating with Extra Arguments

Partial Application of Functions

Back to the Decorator Problem

A Decorator with or without Arguments

Descriptors

__get__(self, instance, owner)

__set__(self, instance, value)

Keeping Track of Instance Data

Introspection

Common Class and Function Attributes

Identifying Object Types

Getting Arbitrary Object Types

Checking for Specific Types

Function Signatures

Handling Default Values

Docstrings

Applied Techniques

Tracking Subclasses

A Simple Plugin Architecture

Now What?

Chapter 3: Models

How Django Processes Model Classes

Setting Attributes on Models

Getting Information About Models

Class Information

Field Definitions

Primary Key Fields

Configuration Options

Accessing the Model Cache

Retrieving All Applications

Retrieving a Single Application

Dealing with Individual Models

Using Model Fields

Common Field Attributes

Common Field Methods

Subclassing Fields

Deciding Whether to Invent or Extend

Performing Actions During Model Registration

contribute_to_class(self, cls, name)

contribute_to_related_class(self, cls, related)

Altering Data Behavior

get_internal_type(self)

validate(self, value, instance)

to_python(self, value)

Supporting Complex Types with SubfieldBase

Controlling Database Behavior

db_type(self, connection)

get_prep_value(self, value)

get_db_prep_value(self, value, connection, prepared=False)

get_db_prep_save(self, value, connection)

get_prep_lookup(self, lookup_type, value)

get_db_prep_lookup(self, lookup_type, value, connection, prepared=False)

Dealing with Files

get_directory_name(self)

get_filename(self, filename)

generate_filename(self, instance, filename)

save_form_data(self, instance, data)

delete_file(self, instance, sender)

attr_class

Customizing the File Class

path(self)

url(self)

size(self)

open(self, mode=‘rb’)

save(self, name, content, save=True)

delete(self, save=True)

Signals

class_prepared

pre_init and post_init

pre_save and post_save

pre_delete and post_delete

post_syncdb

Applied Techniques

Loading Attributes on Demand

Storing Raw Data

Pickling and Unpickling Data

Unpickling on Demand

Putting It All Together

Creating Models Dynamically at Runtime

A First Pass

Adding Model Configuration Options

Now What?

Chapter 4: URLs and Views

URLs

Standard URL Configuration

The patterns() Function

The url( ) Function

The include( ) Function

Resolving URLs to Views

Resolving Views to URLs

The permalink Decorator

The url Template Tag

The reverse( ) Utility Function

Function-Based Views

Templates Break It Up a Bit

Anatomy of a View

Writing Views to Be Generic

Use Lots of Arguments

Provide Sensible Defaults

View Decorators

Applying View Decorators

Writing a View Decorator

Class-Based Views

django.views.generic.base.View

__init__(self, **kwargs)

as_view(cls, **initkwargs)

dispatch(self, request, *args, **kwargs)

Individual View Methods

Decorating View Methods

Using an Object As a View

Applied Techniques

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS)

CORS Decorator

CORS Mixin

Providing Both a Decorator and a Mixin

Now What?

Chapter 5: Forms

Declaring and Identifying Fields

Binding to User Input

Validating Input

Using Class-Based Views

Custom Fields

Validation

Controlling Widgets

Defining HTML Behavior

Custom Widgets

Rendering HTML

Obtaining Values from Posted Data

Splitting Data Across Multiple Widgets

Customizing Form Markup

Accessing Individual Fields

Customizing the Display of Errors

Applied Techniques

Pending and Resuming Forms

Storing Values for Later

Reconstituting a Form

A Full Workflow

Making It Generic

A Class-Based Approach

Now What?

Chapter 6: Templates

What Makes a Template

Exceptions

The Process at Large

Content Tokens

Parsing Tokens into Nodes

Template Nodes

Rendering Templates

Context

Simple Variable Resolution

Complex Variable Lookup

Including Aspects of the Request

Retrieving Templates

django.template.loader.get_template(template_name)

django.template.loader.select_template(template_name_list)

Shortcuts to Load and Render Templates

render_to_string(template_name, dictionary=None, context_instance=None)

render_to_response(template_name, dictionary=None, context_instance=None, content_type=None)

Adding Features for Templates

Setting Up the Package

Variable Filters

Accepting a Value

Accepting an Argument

Returning a Value

Registering As a Filter

Template Tags

A Simple Tag

A Shortcut for Simple Tags

Adding Features to All Templates

Applied Techniques

Embedding Another Template Engine

Converting a Token to a String

Compiling to a Node

Preparing the Jinja Template

Enabling User-Submitted Themes

Setting Up the Models

Supporting Site-Wide Themes

Setting Up Templates to Use Themes

Validating and Securing Themes

An Example Theme

Now What?

Chapter 7: Handling HTTP

Requests and Responses

HttpRequest

HttpRequest.method

“Safe” Methods

“Idempotent” Methods

HttpRequest.path

Accessing Submitted Data

HttpRequest.GET

HttpRequest.POST

HttpRequest.FILES

HttpRequest.raw_post_data

HttpRequest.META

HttpRequest.COOKIES

HttpRequest.get_signed_cookie(key[, …])

HttpRequest.get_host( )

HttpRequest.get_full_path( )

HttpRequest.build_absolute_uri(location=None)

HttpRequest.is_secure( )

HttpRequest.is_ajax( )

HttpRequest.encoding

HttpResponse

Creating a Response

Dictionary Access to Headers

File-Like Access to Content

HttpResponse.status_code

HttpResponse.set_cookie(key, value=''[, …])

HttpResponse.delete_cookie(key, path='/', domain=None)

HttpResponse.cookies

HttpResponse.set_signed_cookie(key, value, salt=''[, …])

HttpResponse.content

Specialty Response Objects

Writing HTTP Middleware

MiddlewareClass.process_request(self, request)

MiddlewareClass.process_view(self, request, view, args, kwargs)

MiddlewareClass.process_response(self, request, response)

MiddlewareClass.process_exception(self, request, exception)

Deciding Between Middleware and View Decorators

Differences in Scope

Configuration Options

Using Middleware As Decorators

Allowing Configuration Options

HTTP-Related Signals

django.core.signals.request_started

django.core.signals.request_finished

django.core.signals.got_request_exception

Applied Techniques

Signing Cookies Automatically

Signing Outgoing Response Cookies

Validating Incoming Request Cookies

Signing Cookies As a Decorator

Now What?

Chapter 8: Backend Protocols

Database Access

django.db.backends

DatabaseWrapper

DatabaseWrapper.features

DatabaseWrapper.ops

Comparison Operators

Obtaining a Cursor

Creation of New Structures

Introspection of Existing Structures

DatabaseClient

DatabaseError and IntegrityError

Authentication

get_user(user_id)

authenticate(**credentials)

Storing User Information

Files

The Base File Class

Handling Uploads

Storing Files

Session Management

Caching

Specifying a Backend

Using the Cache Manually

Template Loading

load_template_source(template_name, template_dirs=None)

load_template_source.is_usable

load_template(template_name, template_dirs=None)

Context Processors

Applied Techniques

Scanning Incoming Files for Viruses

Now What?

Chapter 9: Common Tools

Core Exceptions (django.core.exceptions)

ImproperlyConfigured

MiddlewareNotUsed

MultipleObjectsReturned

ObjectDoesNotExist

PermissionDenied

SuspiciousOperation

ValidationError

ViewDoesNotExist

Text Modification (django.utils.text)

compress_string(s)

compress_sequence(sequence)

get_text_list(items, last_word='or')

javascript_quote(s, quote_double_quotes=False)

normalize_newlines(text)

phone2numeric(phone)

recapitalize(text)

slugify(value)

smart_split(text)

unescape_entities(text)

unescape_string_literal(s)

wrap(text, width)

Truncating Text

Truncator.chars(num, truncate='…')

Truncator.words(num, truncate='…', html=False)

Data Structures (django.utils.datastructures)

DictWrapper

ImmutableList

MergeDict

MultiValueDict

SortedDict

Functional Utilities (django.utils.functional)

cached_property(func)

curry(func)

lazy(func, *resultclasses)

allow_lazy(func, *resultclasses)

lazy_property(fget=None, fset=None, fdel=None)

memoize(func, cache, num_args)

partition(predicate, values)

wraps(func)

Signals

How It Works

Defining a Signal

Sending a Signal

Capturing Return Values

Defining a Listener

Registering Listeners

Forcing Strong References

Now What?

Chapter 10: Coordinating Applications

Contacts

contacts.models.Contact

contacts.forms.UserEditorForm

contacts.forms.ContactEditorForm

contacts.views.EditContact

Admin Configuration

URL Configuration

Real Estate Properties

properties.models.Property

properties.models.Feature

properties.models.PropertyFeature

properties.models.InterestedParty

Admin Configuration

URL Configuration

Now What?

Chapter 11: Enhancing Applications

Adding an API

Serializing Data

Outputting a Single Object

Handling Relationships

Controlling Output Fields

Many-to-Many Relationships

Getting the Appropriate Fields

Getting Information About the Relationship

Retrieving Data

ResourceView

ResourceListView

ResourceDetailView

Now What?

Index

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc