6

1

0

2

r

a

M

9

2

]

G

L

.

s

c

[

4

v

9

3

9

6

0

.

1

1

5

1

:

v

i

X

r

a

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2016

SESSION-BASED RECOMMENDATIONS WITH

RECURRENT NEURAL NETWORKS

Bal´azs Hidasi ∗

Gravity R&D Inc.

Budapest, Hungary

balazs.hidasi@gravityrd.com

Alexandros Karatzoglou

Telefonica Research

Barcelona, Spain

alexk@tid.es

Linas Baltrunas †

Netflix

Los Gatos, CA, USA

lbaltrunas@netflix.com

Domonkos Tikk

Gravity R&D Inc.

Budapest, Hungary

domonkos.tikk@gravityrd.com

ABSTRACT

We apply recurrent neural networks (RNN) on a new domain, namely recom-

mender systems. Real-life recommender systems often face the problem of having

to base recommendations only on short session-based data (e.g. a small sportsware

website) instead of long user histories (as in the case of Netflix). In this situation

the frequently praised matrix factorization approaches are not accurate. This prob-

lem is usually overcome in practice by resorting to item-to-item recommendations,

i.e. recommending similar items. We argue that by modeling the whole session,

more accurate recommendations can be provided. We therefore propose an RNN-

based approach for session-based recommendations. Our approach also considers

practical aspects of the task and introduces several modifications to classic RNNs

such as a ranking loss function that make it more viable for this specific problem.

Experimental results on two data-sets show marked improvements over widely

used approaches.

1

INTRODUCTION

Session-based recommendation is a relatively unappreciated problem in the machine learning and

recommender systems community. Many e-commerce recommender systems (particularly those

of small retailers) and most of news and media sites do not typically track the user-id’s of the

users that visit their sites over a long period of time. While cookies and browser fingerprinting

can provide some level of user recognizability, those technologies are often not reliable enough and

moreover raise privacy concerns. Even if tracking is possible, lots of users have only one or two

sessions on a smaller e-commerce site, and in certain domains (e.g. classified sites) the behavior

of users often shows session-based traits. Thus subsequent sessions of the same user should be

handled independently. Consequently, most session-based recommendation systems deployed for

e-commerce are based on relatively simple methods that do not make use of a user profile e.g. item-

to-item similarity, co-occurrence, or transition probabilities. While effective, those methods often

take only the last click or selection of the user into account ignoring the information of past clicks.

The most common methods used in recommender systems are factor models (Koren et al., 2009;

Weimer et al., 2007; Hidasi & Tikk, 2012) and neighborhood methods (Sarwar et al., 2001; Ko-

ren, 2008). Factor models work by decomposing the sparse user-item interactions matrix to a set

of d dimensional vectors one for each item and user in the dataset. The recommendation problem

is then treated as a matrix completion/reconstruction problem whereby the latent factor vectors are

then used to fill the missing entries by e.g. taking the dot product of the corresponding user–item

latent factors. Factor models are hard to apply in session-based recommendation due to the absence

∗The author spent 3 months at Telefonica Research during the research of this topic.

†This work was done while the author was a member of the Telefonica Research group in Barcelona, Spain

1

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2016

of a user profile. On the other hand, neighborhood methods, which rely on computing similari-

ties between items (or users) are based on co-occurrences of items in sessions (or user profiles).

Neighborhood methods have been used extensively in session-based recommendations.

The past few years have seen the tremendous success of deep neural networks in a number of tasks

such as image and speech recognition (Russakovsky et al., 2014; Hinton et al., 2012) where unstruc-

tured data is processed through several convolutional and standard layers of (usually rectified linear)

units. Sequential data modeling has recently also attracted a lot of attention with various flavors of

RNNs being the model of choice for this type of data. Applications of sequence modeling range

from test-translation to conversation modeling to image captioning.

While RNNs have been applied to the aforementioned domains with remarkable success little atten-

tion, has been paid to the area of recommender systems. In this work we argue that RNNs can be

applied to session-based recommendation with remarkable results, we deal with the issues that arise

when modeling such sparse sequential data and also adapt the RNN models to the recommender

setting by introducing a new ranking loss function suited to the task of training these models. The

session-based recommendation problem shares some similarities with some NLP-related problems

in terms of modeling as long as they both deals with sequences. In the session-based recommenda-

tion we can consider the first item a user clicks when entering a web-site as the initial input of the

RNN, we then would like to query the model based on this initial input for a recommendation. Each

consecutive click of the user will then produce an output (a recommendation) that depends on all

the previous clicks. Typically the item-set to choose from in recommenders systems can be in the

tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands. Apart from the large size of the item set, another

challenge is that click-stream datasets are typically quite large thus training time and scalability are

really important. As in most information retrieval and recommendation settings, we are interested

in focusing the modeling power on the top-items that the user might be interested in, to this end we

use ranking loss function to train the RNNs.

2 RELATED WORK

2.1 SESSION-BASED RECOMMENDATION

Much of the work in the area of recommender systems has focused on models that work when a

user identifier is available and a clear user profile can be built. In this setting, matrix factorization

methods and neighborhood models have dominated the literature and are also employed on-line. One

of the main approaches that is employed in session-based recommendation and a natural solution to

the problem of a missing user profile is the item-to-item recommendation approach (Sarwar et al.,

2001; Linden et al., 2003) in this setting an item to item similarity matrix is precomputed from

the available session data, that is items that are often clicked together in sessions are deemed to be

similar. This similarity matrix is then simply used during the session to recommend the most similar

items to the one the user has currently clicked. While simple, this method has been proven to be

effective and is widely employed. While effective, these methods are only taking into account the

last click of the user, in effect ignoring the information of the past clicks.

A somewhat different approach to session-based recommendation are Markov Decision Processes

(MDPs) (Shani et al., 2002). MDPs are models of sequential stochastic decision problems. An MDP

is defined as a four-tuple S, A, Rwd, tr where S is the set of states, A is a set of actions Rwd is

a reward function and tr is the state-transition function. In recommender systems actions can be

equated with recommendations and the simplest MPDs are essentially first order Markov chains

where the next recommendation can be simply computed on the basis of the transition probability

between items. The main issue with applying Markov chains in session-based recommendation is

that the state space quickly becomes unmanageable when trying to include all possible sequences of

user selections.

The extended version of the General Factorization Framework (GFF) (Hidasi & Tikk, 2015) is ca-

pable of using session data for recommendations. It models a session by the sum of its events. It

uses two kinds of latent representations for items, one represents the item itself, the other is for

representing the item as part of a session. The session is then represented as the average of the

feature vectors of part-of-a-session item representation. However, this approach does not consider

any ordering within the session.

2

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2016

2.2 DEEP LEARNING IN RECOMMENDERS

One of the first related methods in the neural networks literature where the use of Restricted Boltz-

mann Machines (RBM) for Collaborative Filtering (Salakhutdinov et al., 2007). In this work an

RBM is used to model user-item interaction and perform recommendations. This model has been

shown to be one of the best performing Collaborative Filtering models. Deep Models have been used

to extract features from unstructured content such as music or images that are then used together with

more conventional collaborative filtering models. In Van den Oord et al. (2013) a convolutional deep

network is used to extract feature from music files that are then used in a factor model. More recently

Wang et al. (2015) introduced a more generic approach whereby a deep network is used to extract

generic content-features from any types of items, these features are then incorporated in a standard

collaborative filtering model to enhance the recommendation performance. This approach seems to

be particularly useful in settings where there is not sufficient user-item interaction information.

3 RECOMMENDATIONS WITH RNNS

Recurrent Neural Networks have been devised to model variable-length sequence data. The main

difference between RNNs and conventional feedforward deep models is the existence of an internal

hidden state in the units that compose the network. Standard RNNs update their hidden state h using

the following update function:

ht = g(W xt + U ht−1)

(1)

Where g is a smooth and bounded function such as a logistic sigmoid function xt is the input of

the unit at time t. An RNN outputs a probability distribution over the next element of the sequence,

given its current state ht.

A Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) (Cho et al., 2014) is a more elaborate model of an RNN unit that

aims at dealing with the vanishing gradient problem. GRU gates essentially learn when and by how

much to update the hidden state of the unit. The activation of the GRU is a linear interpolation

between the previous activation and the candidate activation ˆht:

ht = (1 − zt)ht−1 + zt ˆht

(2)

where the update gate is given by:

zt = σ(Wzxt + Uzht−1)

while the candidate activation function ˆht is computed in a similar manner:

ˆht = tanh (W xt + U (rt ht−1))

and finaly the reset gate rt is given by:

rt = σ(Wrxt + Urht−1)

3.1 CUSTOMIZING THE GRU MODEL

(3)

(4)

(5)

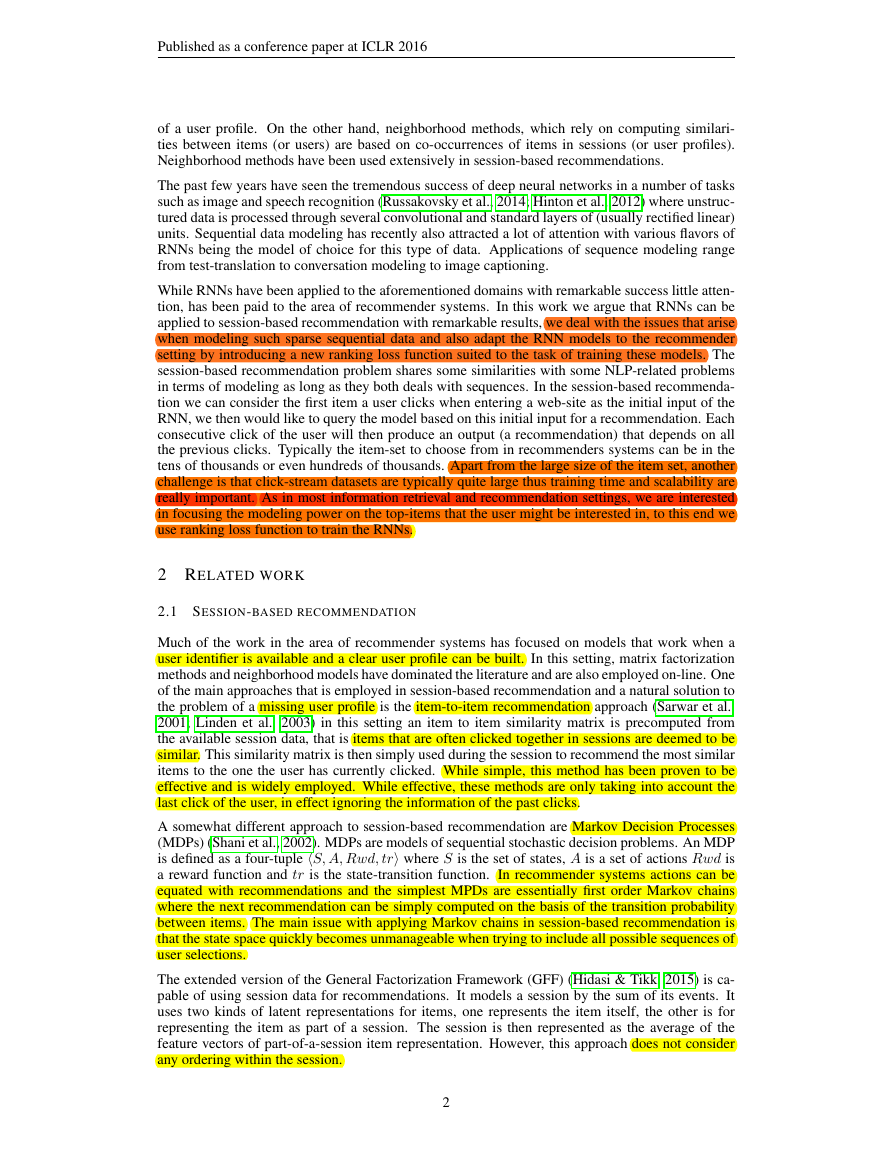

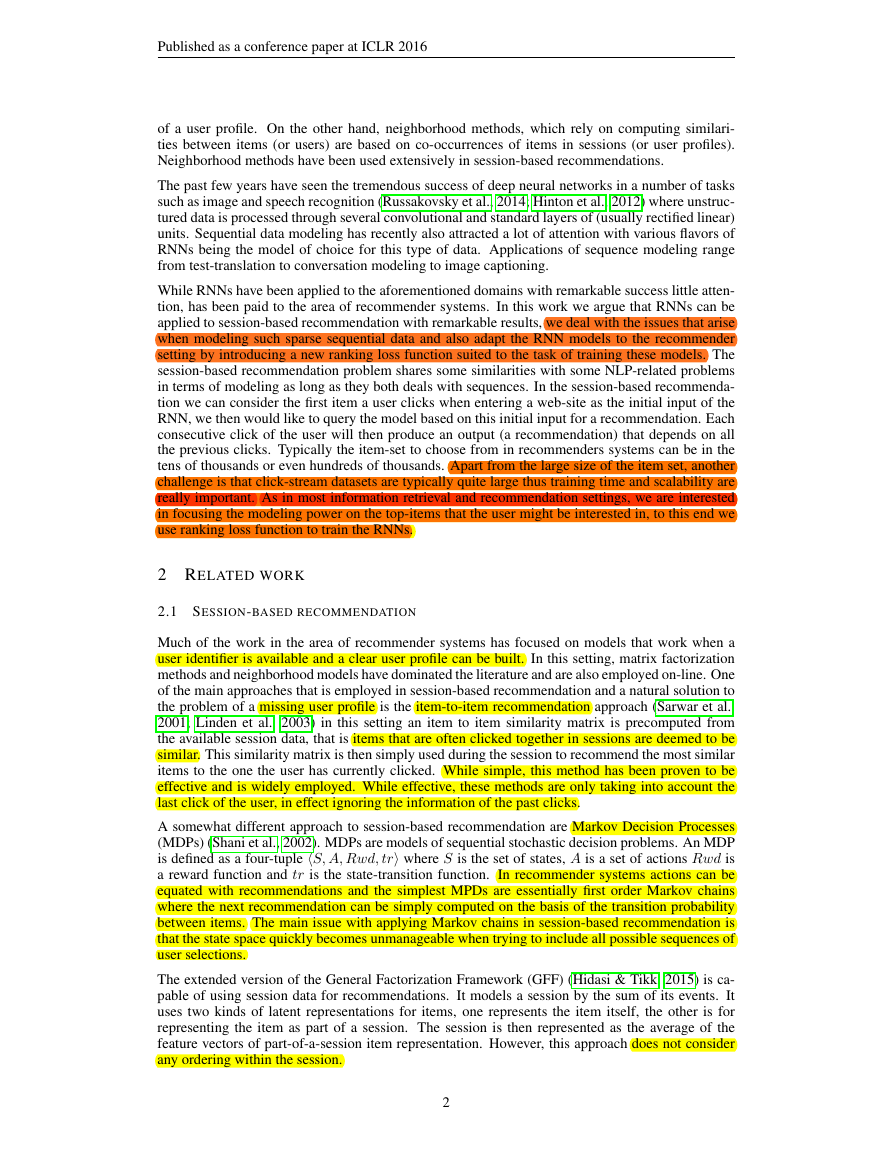

We used the GRU-based RNN in our models for session-based recommendations. The input of the

network is the actual state of the session while the output is the item of the next event in the session.

The state of the session can either be the item of the actual event or the events in the session so

far. In the former case 1-of-N encoding is used, i.e. the input vector’s length equals to the number

of items and only the coordinate corresponding to the active item is one, the others are zeros. The

latter setting uses a weighted sum of these representations, in which events are discounted if they

have occurred earlier. For the stake of stability, the input vector is then normalized. We expect this

to help because it reinforces the memory effect: the reinforcement of very local ordering constraints

which are not well captured by the longer memory of RNN. We also experimented with adding an

additional embedding layer, but the 1-of-N encoding always performed better.

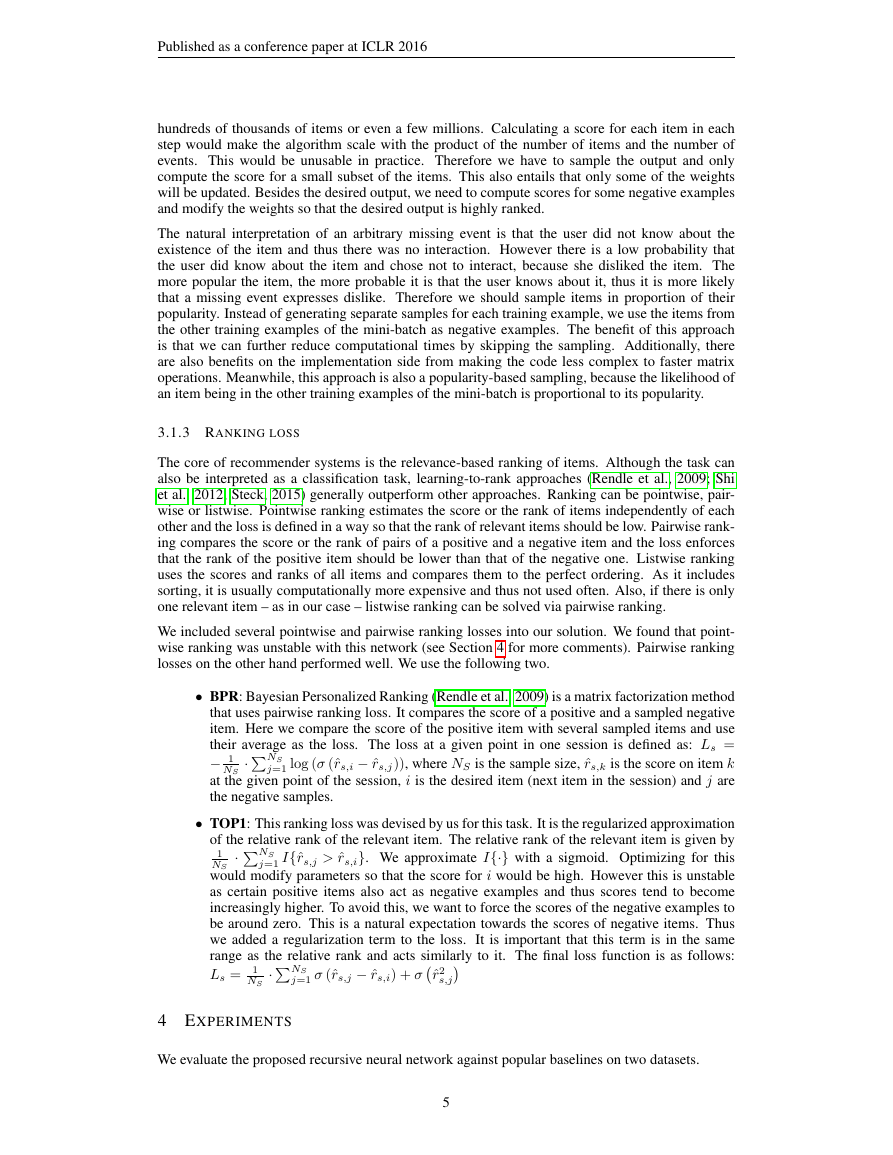

The core of the network is the GRU layer(s) and additional feedforward layers can be added between

the last layer and the output. The output is the predicted preference of the items, i.e. the likelihood

of being the next in the session for each item. When multiple GRU layers are used, the hidden

state of the previous layer is the input of the next one. The input can also be optionally connected

3

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2016

Figure 1: General architecture of the network. Processing of one event of the event stream at once.

to GRU layers deeper in the network, as we found that this improves performance. See the whole

architecture on Figure 1, which depicts the representation of a single event within a time series of

events.

Since recommender systems are not the primary application area of recurrent neural networks, we

modified the base network to better suit the task. We also considered practical points so that our

solution could be possibly applied in a live environment.

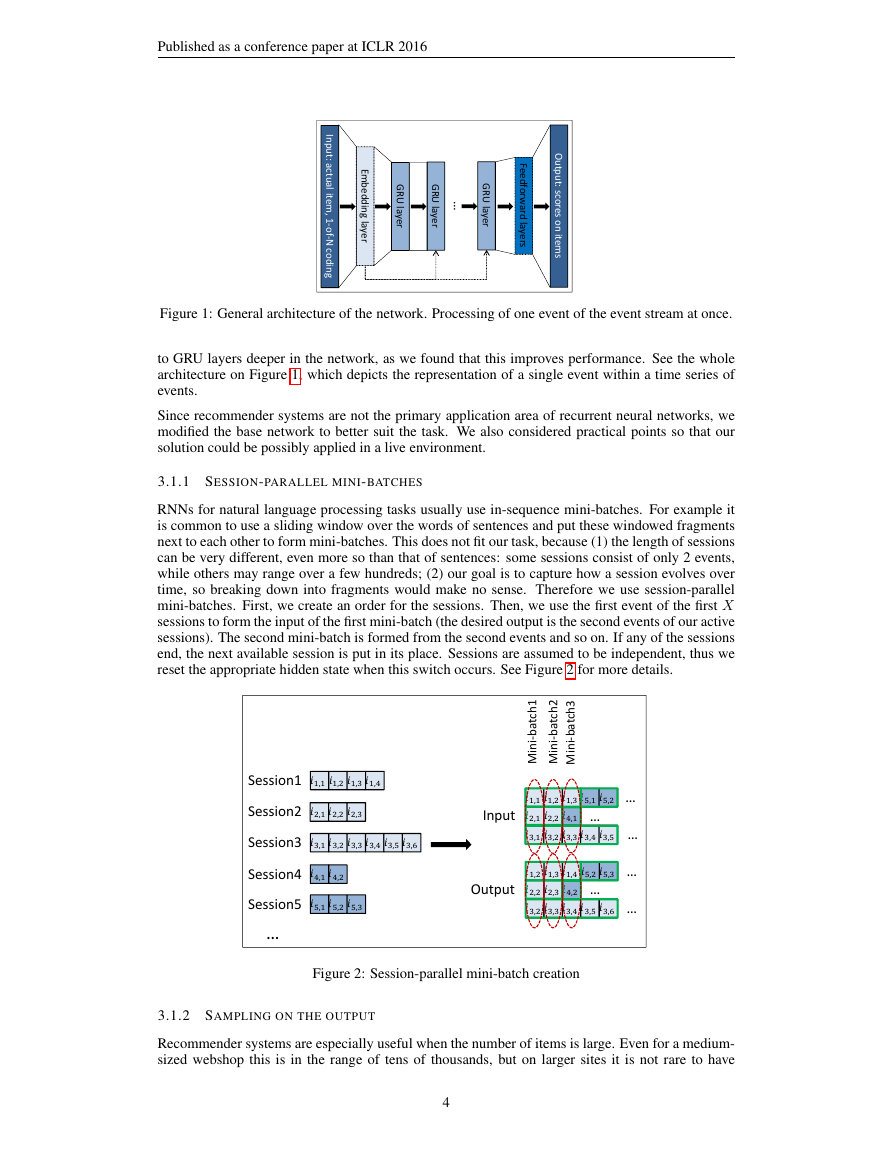

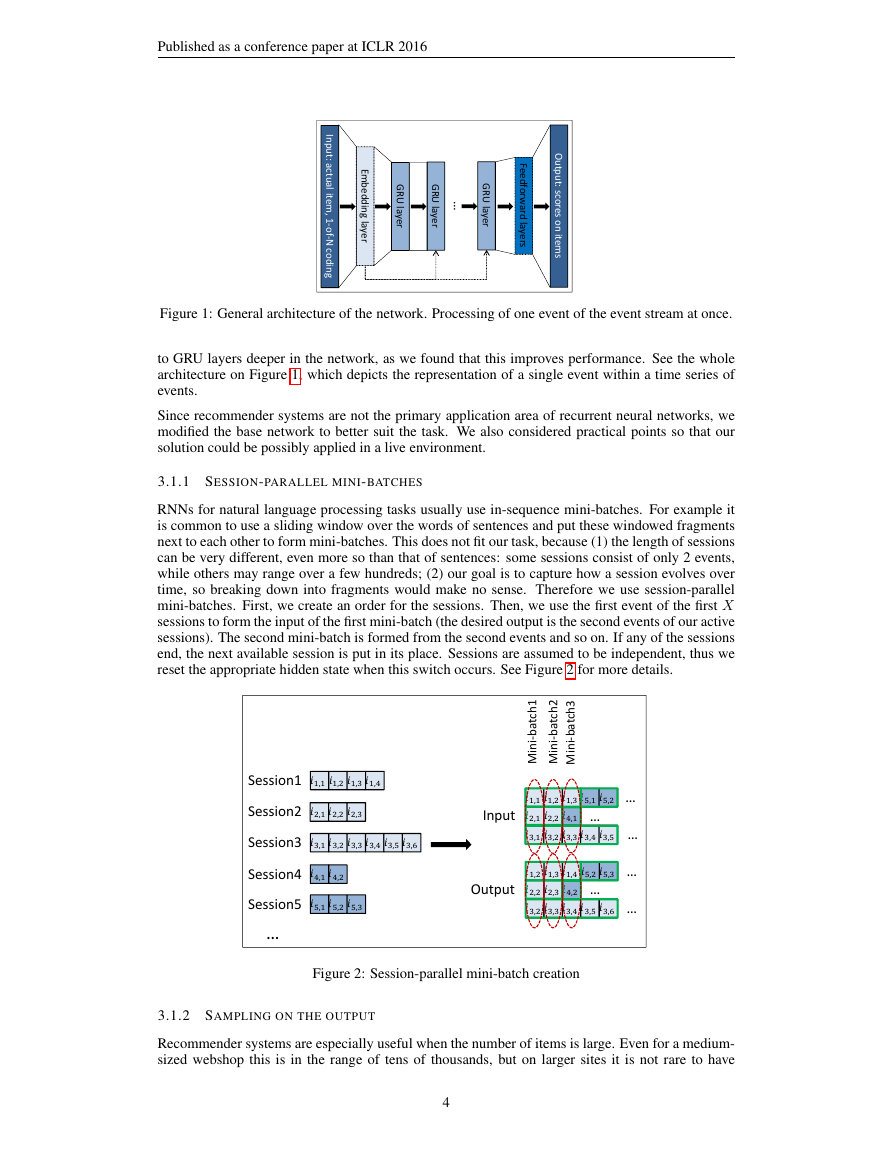

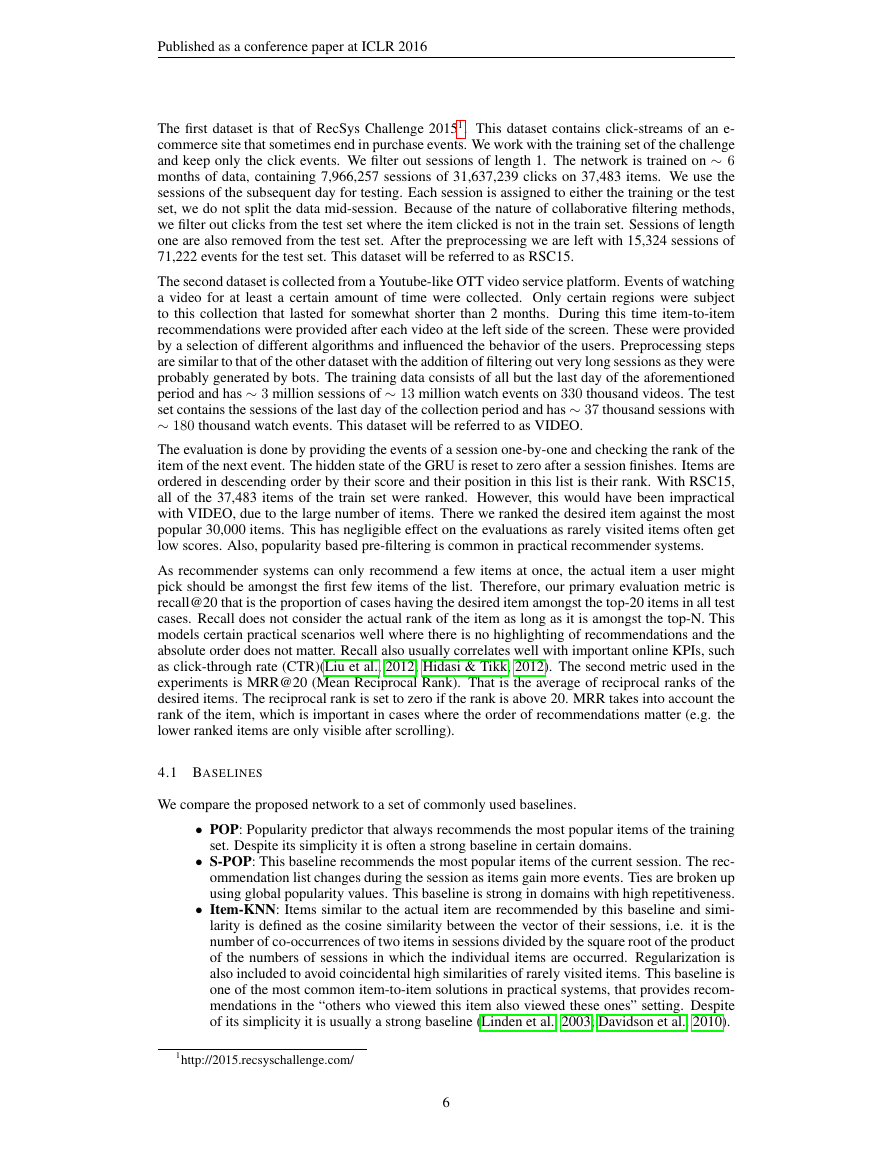

3.1.1 SESSION-PARALLEL MINI-BATCHES

RNNs for natural language processing tasks usually use in-sequence mini-batches. For example it

is common to use a sliding window over the words of sentences and put these windowed fragments

next to each other to form mini-batches. This does not fit our task, because (1) the length of sessions

can be very different, even more so than that of sentences: some sessions consist of only 2 events,

while others may range over a few hundreds; (2) our goal is to capture how a session evolves over

time, so breaking down into fragments would make no sense. Therefore we use session-parallel

mini-batches. First, we create an order for the sessions. Then, we use the first event of the first X

sessions to form the input of the first mini-batch (the desired output is the second events of our active

sessions). The second mini-batch is formed from the second events and so on. If any of the sessions

end, the next available session is put in its place. Sessions are assumed to be independent, thus we

reset the appropriate hidden state when this switch occurs. See Figure 2 for more details.

Figure 2: Session-parallel mini-batch creation

3.1.2 SAMPLING ON THE OUTPUT

Recommender systems are especially useful when the number of items is large. Even for a medium-

sized webshop this is in the range of tens of thousands, but on larger sites it is not rare to have

4

GRU layerFeedforwardlayersGRU layerInput: actualitem, 1-of-N codingEmbeddinglayerGRU layer…Output: scoresonitems,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,Session1Session2Session3Session4Session5…,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,InputOutputMini-batch1Mini-batch2Mini-batch3………………�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2016

hundreds of thousands of items or even a few millions. Calculating a score for each item in each

step would make the algorithm scale with the product of the number of items and the number of

events. This would be unusable in practice. Therefore we have to sample the output and only

compute the score for a small subset of the items. This also entails that only some of the weights

will be updated. Besides the desired output, we need to compute scores for some negative examples

and modify the weights so that the desired output is highly ranked.

The natural interpretation of an arbitrary missing event is that the user did not know about the

existence of the item and thus there was no interaction. However there is a low probability that

the user did know about the item and chose not to interact, because she disliked the item. The

more popular the item, the more probable it is that the user knows about it, thus it is more likely

that a missing event expresses dislike. Therefore we should sample items in proportion of their

popularity. Instead of generating separate samples for each training example, we use the items from

the other training examples of the mini-batch as negative examples. The benefit of this approach

is that we can further reduce computational times by skipping the sampling. Additionally, there

are also benefits on the implementation side from making the code less complex to faster matrix

operations. Meanwhile, this approach is also a popularity-based sampling, because the likelihood of

an item being in the other training examples of the mini-batch is proportional to its popularity.

3.1.3 RANKING LOSS

The core of recommender systems is the relevance-based ranking of items. Although the task can

also be interpreted as a classification task, learning-to-rank approaches (Rendle et al., 2009; Shi

et al., 2012; Steck, 2015) generally outperform other approaches. Ranking can be pointwise, pair-

wise or listwise. Pointwise ranking estimates the score or the rank of items independently of each

other and the loss is defined in a way so that the rank of relevant items should be low. Pairwise rank-

ing compares the score or the rank of pairs of a positive and a negative item and the loss enforces

that the rank of the positive item should be lower than that of the negative one. Listwise ranking

uses the scores and ranks of all items and compares them to the perfect ordering. As it includes

sorting, it is usually computationally more expensive and thus not used often. Also, if there is only

one relevant item – as in our case – listwise ranking can be solved via pairwise ranking.

We included several pointwise and pairwise ranking losses into our solution. We found that point-

wise ranking was unstable with this network (see Section 4 for more comments). Pairwise ranking

losses on the other hand performed well. We use the following two.

• BPR: Bayesian Personalized Ranking (Rendle et al., 2009) is a matrix factorization method

that uses pairwise ranking loss. It compares the score of a positive and a sampled negative

item. Here we compare the score of the positive item with several sampled items and use

their average as the loss. The loss at a given point in one session is defined as: Ls =

− 1

j=1 log (σ (ˆrs,i − ˆrs,j)), where NS is the sample size, ˆrs,k is the score on item k

at the given point of the session, i is the desired item (next item in the session) and j are

the negative samples.

·NS

NS

·NS

• TOP1: This ranking loss was devised by us for this task. It is the regularized approximation

of the relative rank of the relevant item. The relative rank of the relevant item is given by

j=1 I{ˆrs,j > ˆrs,i}. We approximate I{·} with a sigmoid. Optimizing for this

1

NS

would modify parameters so that the score for i would be high. However this is unstable

as certain positive items also act as negative examples and thus scores tend to become

increasingly higher. To avoid this, we want to force the scores of the negative examples to

be around zero. This is a natural expectation towards the scores of negative items. Thus

we added a regularization term to the loss. It is important that this term is in the same

range as the relative rank and acts similarly to it. The final loss function is as follows:

Ls = 1

NS

j=1 σ (ˆrs,j − ˆrs,i) + σˆr2

·NS

s,j

4 EXPERIMENTS

We evaluate the proposed recursive neural network against popular baselines on two datasets.

5

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2016

The first dataset is that of RecSys Challenge 20151. This dataset contains click-streams of an e-

commerce site that sometimes end in purchase events. We work with the training set of the challenge

and keep only the click events. We filter out sessions of length 1. The network is trained on ∼ 6

months of data, containing 7,966,257 sessions of 31,637,239 clicks on 37,483 items. We use the

sessions of the subsequent day for testing. Each session is assigned to either the training or the test

set, we do not split the data mid-session. Because of the nature of collaborative filtering methods,

we filter out clicks from the test set where the item clicked is not in the train set. Sessions of length

one are also removed from the test set. After the preprocessing we are left with 15,324 sessions of

71,222 events for the test set. This dataset will be referred to as RSC15.

The second dataset is collected from a Youtube-like OTT video service platform. Events of watching

a video for at least a certain amount of time were collected. Only certain regions were subject

to this collection that lasted for somewhat shorter than 2 months. During this time item-to-item

recommendations were provided after each video at the left side of the screen. These were provided

by a selection of different algorithms and influenced the behavior of the users. Preprocessing steps

are similar to that of the other dataset with the addition of filtering out very long sessions as they were

probably generated by bots. The training data consists of all but the last day of the aforementioned

period and has ∼ 3 million sessions of ∼ 13 million watch events on 330 thousand videos. The test

set contains the sessions of the last day of the collection period and has ∼ 37 thousand sessions with

∼ 180 thousand watch events. This dataset will be referred to as VIDEO.

The evaluation is done by providing the events of a session one-by-one and checking the rank of the

item of the next event. The hidden state of the GRU is reset to zero after a session finishes. Items are

ordered in descending order by their score and their position in this list is their rank. With RSC15,

all of the 37,483 items of the train set were ranked. However, this would have been impractical

with VIDEO, due to the large number of items. There we ranked the desired item against the most

popular 30,000 items. This has negligible effect on the evaluations as rarely visited items often get

low scores. Also, popularity based pre-filtering is common in practical recommender systems.

As recommender systems can only recommend a few items at once, the actual item a user might

pick should be amongst the first few items of the list. Therefore, our primary evaluation metric is

recall@20 that is the proportion of cases having the desired item amongst the top-20 items in all test

cases. Recall does not consider the actual rank of the item as long as it is amongst the top-N. This

models certain practical scenarios well where there is no highlighting of recommendations and the

absolute order does not matter. Recall also usually correlates well with important online KPIs, such

as click-through rate (CTR)(Liu et al., 2012; Hidasi & Tikk, 2012). The second metric used in the

experiments is MRR@20 (Mean Reciprocal Rank). That is the average of reciprocal ranks of the

desired items. The reciprocal rank is set to zero if the rank is above 20. MRR takes into account the

rank of the item, which is important in cases where the order of recommendations matter (e.g. the

lower ranked items are only visible after scrolling).

4.1 BASELINES

We compare the proposed network to a set of commonly used baselines.

set. Despite its simplicity it is often a strong baseline in certain domains.

• POP: Popularity predictor that always recommends the most popular items of the training

• S-POP: This baseline recommends the most popular items of the current session. The rec-

ommendation list changes during the session as items gain more events. Ties are broken up

using global popularity values. This baseline is strong in domains with high repetitiveness.

• Item-KNN: Items similar to the actual item are recommended by this baseline and simi-

larity is defined as the cosine similarity between the vector of their sessions, i.e. it is the

number of co-occurrences of two items in sessions divided by the square root of the product

of the numbers of sessions in which the individual items are occurred. Regularization is

also included to avoid coincidental high similarities of rarely visited items. This baseline is

one of the most common item-to-item solutions in practical systems, that provides recom-

mendations in the “others who viewed this item also viewed these ones” setting. Despite

of its simplicity it is usually a strong baseline (Linden et al., 2003; Davidson et al., 2010).

1http://2015.recsyschallenge.com/

6

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2016

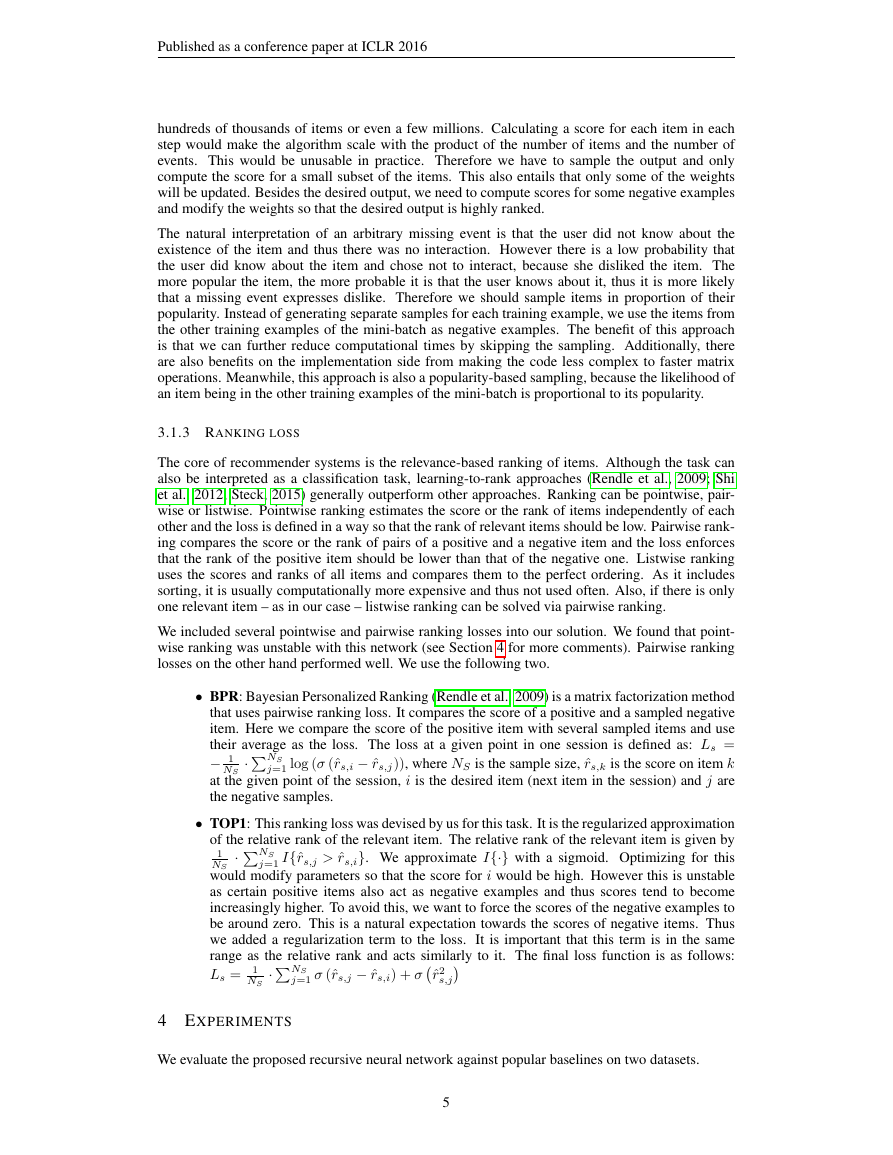

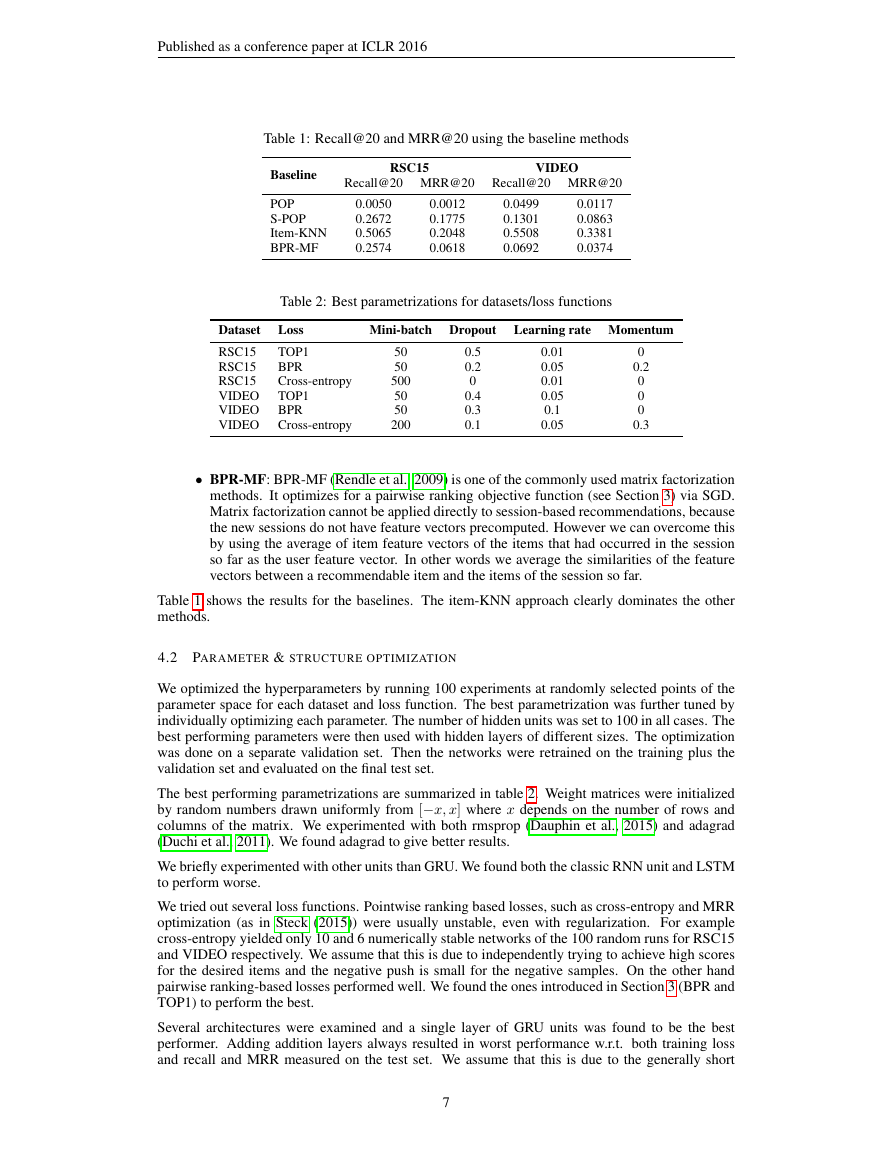

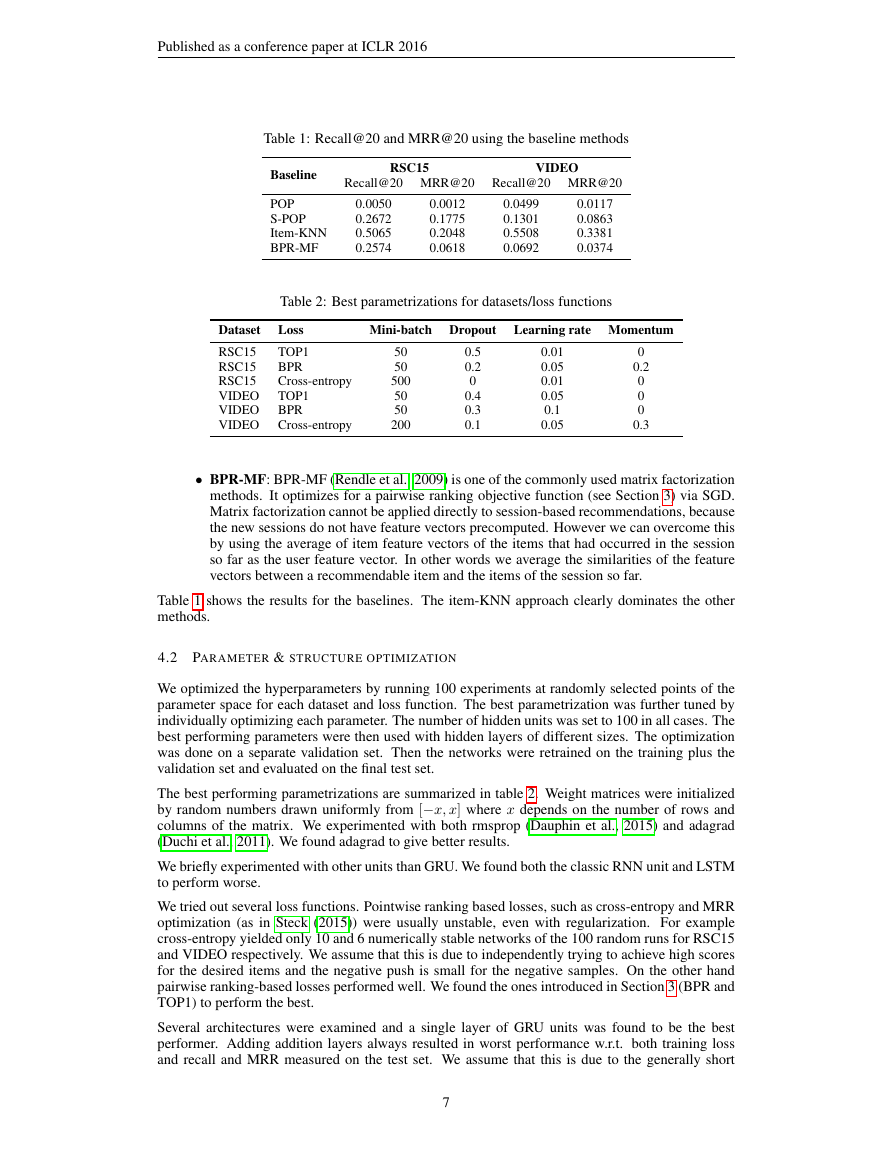

Table 1: Recall@20 and MRR@20 using the baseline methods

Baseline

POP

S-POP

Item-KNN

BPR-MF

RSC15

VIDEO

Recall@20 MRR@20 Recall@20 MRR@20

0.0050

0.2672

0.5065

0.2574

0.0012

0.1775

0.2048

0.0618

0.0499

0.1301

0.5508

0.0692

0.0117

0.0863

0.3381

0.0374

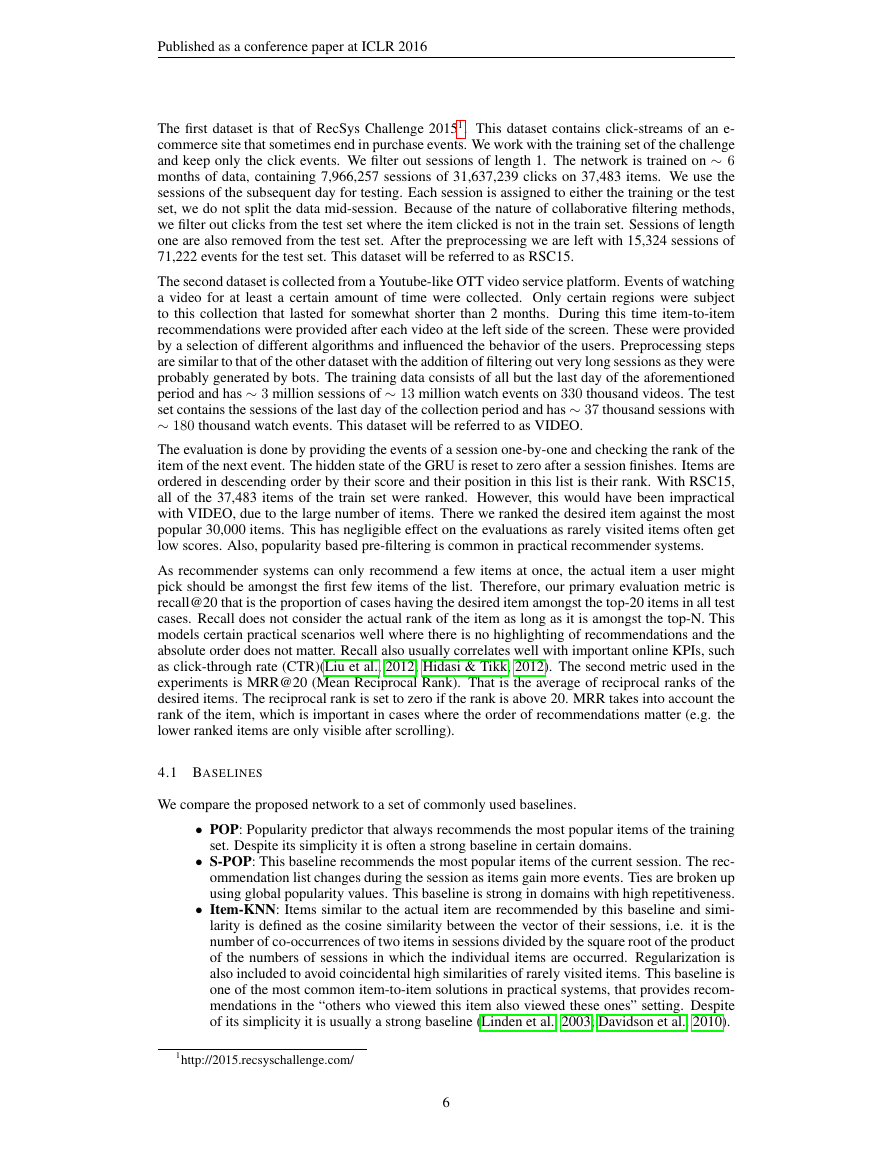

Table 2: Best parametrizations for datasets/loss functions

Dataset Loss

TOP1

RSC15

BPR

RSC15

Cross-entropy

RSC15

TOP1

VIDEO

VIDEO

BPR

Cross-entropy

VIDEO

Mini-batch Dropout Learning rate Momentum

50

50

500

50

50

200

0.5

0.2

0

0.4

0.3

0.1

0.01

0.05

0.01

0.05

0.1

0.05

0

0.2

0

0

0

0.3

• BPR-MF: BPR-MF (Rendle et al., 2009) is one of the commonly used matrix factorization

methods. It optimizes for a pairwise ranking objective function (see Section 3) via SGD.

Matrix factorization cannot be applied directly to session-based recommendations, because

the new sessions do not have feature vectors precomputed. However we can overcome this

by using the average of item feature vectors of the items that had occurred in the session

so far as the user feature vector. In other words we average the similarities of the feature

vectors between a recommendable item and the items of the session so far.

Table 1 shows the results for the baselines. The item-KNN approach clearly dominates the other

methods.

4.2 PARAMETER & STRUCTURE OPTIMIZATION

We optimized the hyperparameters by running 100 experiments at randomly selected points of the

parameter space for each dataset and loss function. The best parametrization was further tuned by

individually optimizing each parameter. The number of hidden units was set to 100 in all cases. The

best performing parameters were then used with hidden layers of different sizes. The optimization

was done on a separate validation set. Then the networks were retrained on the training plus the

validation set and evaluated on the final test set.

The best performing parametrizations are summarized in table 2. Weight matrices were initialized

by random numbers drawn uniformly from [−x, x] where x depends on the number of rows and

columns of the matrix. We experimented with both rmsprop (Dauphin et al., 2015) and adagrad

(Duchi et al., 2011). We found adagrad to give better results.

We briefly experimented with other units than GRU. We found both the classic RNN unit and LSTM

to perform worse.

We tried out several loss functions. Pointwise ranking based losses, such as cross-entropy and MRR

optimization (as in Steck (2015)) were usually unstable, even with regularization. For example

cross-entropy yielded only 10 and 6 numerically stable networks of the 100 random runs for RSC15

and VIDEO respectively. We assume that this is due to independently trying to achieve high scores

for the desired items and the negative push is small for the negative samples. On the other hand

pairwise ranking-based losses performed well. We found the ones introduced in Section 3 (BPR and

TOP1) to perform the best.

Several architectures were examined and a single layer of GRU units was found to be the best

performer. Adding addition layers always resulted in worst performance w.r.t. both training loss

and recall and MRR measured on the test set. We assume that this is due to the generally short

7

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2016

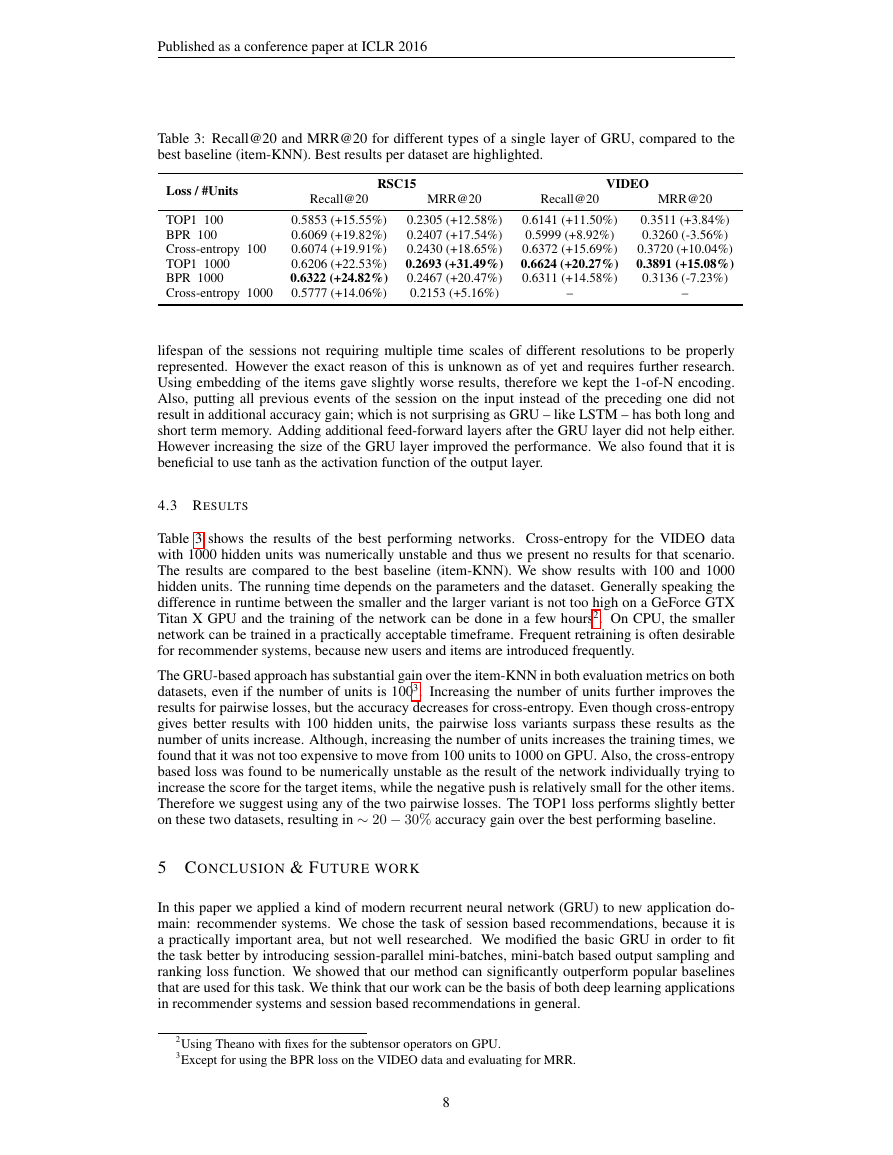

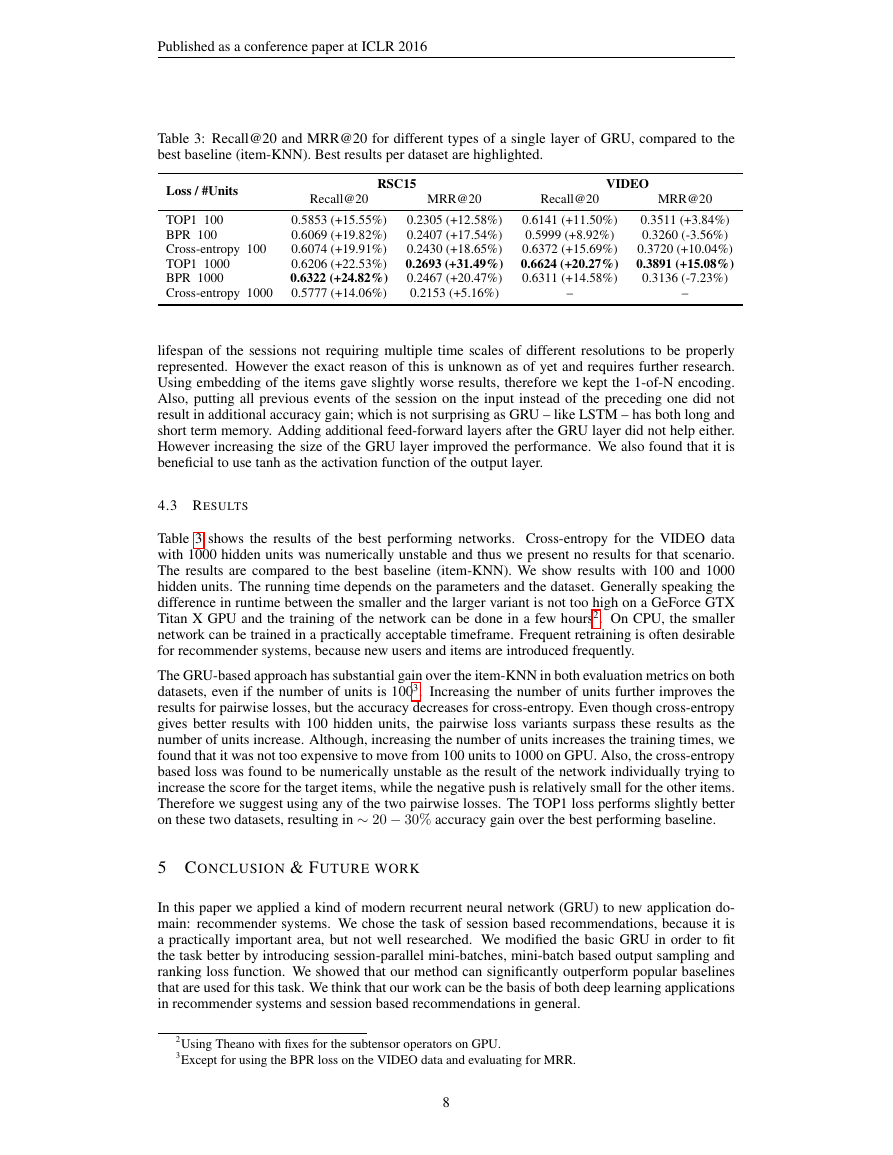

Table 3: Recall@20 and MRR@20 for different types of a single layer of GRU, compared to the

best baseline (item-KNN). Best results per dataset are highlighted.

Loss / #Units

RSC15

Recall@20

MRR@20

Recall@20

VIDEO

MRR@20

TOP1 100

BPR 100

Cross-entropy 100

TOP1 1000

BPR 1000

Cross-entropy 1000

0.5853 (+15.55%)

0.6069 (+19.82%)

0.6074 (+19.91%)

0.6206 (+22.53%)

0.6322 (+24.82%)

0.5777 (+14.06%)

0.2305 (+12.58%)

0.2407 (+17.54%)

0.2430 (+18.65%)

0.2693 (+31.49%)

0.2467 (+20.47%)

0.2153 (+5.16%)

0.6141 (+11.50%)

0.5999 (+8.92%)

0.6372 (+15.69%)

0.6624 (+20.27%)

0.6311 (+14.58%)

–

0.3511 (+3.84%)

0.3260 (-3.56%)

0.3720 (+10.04%)

0.3891 (+15.08%)

0.3136 (-7.23%)

–

lifespan of the sessions not requiring multiple time scales of different resolutions to be properly

represented. However the exact reason of this is unknown as of yet and requires further research.

Using embedding of the items gave slightly worse results, therefore we kept the 1-of-N encoding.

Also, putting all previous events of the session on the input instead of the preceding one did not

result in additional accuracy gain; which is not surprising as GRU – like LSTM – has both long and

short term memory. Adding additional feed-forward layers after the GRU layer did not help either.

However increasing the size of the GRU layer improved the performance. We also found that it is

beneficial to use tanh as the activation function of the output layer.

4.3 RESULTS

Table 3 shows the results of the best performing networks. Cross-entropy for the VIDEO data

with 1000 hidden units was numerically unstable and thus we present no results for that scenario.

The results are compared to the best baseline (item-KNN). We show results with 100 and 1000

hidden units. The running time depends on the parameters and the dataset. Generally speaking the

difference in runtime between the smaller and the larger variant is not too high on a GeForce GTX

Titan X GPU and the training of the network can be done in a few hours2. On CPU, the smaller

network can be trained in a practically acceptable timeframe. Frequent retraining is often desirable

for recommender systems, because new users and items are introduced frequently.

The GRU-based approach has substantial gain over the item-KNN in both evaluation metrics on both

datasets, even if the number of units is 1003. Increasing the number of units further improves the

results for pairwise losses, but the accuracy decreases for cross-entropy. Even though cross-entropy

gives better results with 100 hidden units, the pairwise loss variants surpass these results as the

number of units increase. Although, increasing the number of units increases the training times, we

found that it was not too expensive to move from 100 units to 1000 on GPU. Also, the cross-entropy

based loss was found to be numerically unstable as the result of the network individually trying to

increase the score for the target items, while the negative push is relatively small for the other items.

Therefore we suggest using any of the two pairwise losses. The TOP1 loss performs slightly better

on these two datasets, resulting in ∼ 20 − 30% accuracy gain over the best performing baseline.

5 CONCLUSION & FUTURE WORK

In this paper we applied a kind of modern recurrent neural network (GRU) to new application do-

main: recommender systems. We chose the task of session based recommendations, because it is

a practically important area, but not well researched. We modified the basic GRU in order to fit

the task better by introducing session-parallel mini-batches, mini-batch based output sampling and

ranking loss function. We showed that our method can significantly outperform popular baselines

that are used for this task. We think that our work can be the basis of both deep learning applications

in recommender systems and session based recommendations in general.

2Using Theano with fixes for the subtensor operators on GPU.

3Except for using the BPR loss on the VIDEO data and evaluating for MRR.

8

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc