Short Math Guide for LATEX

Michael Downes

American Mathematical Society

Version 1.09 (2002-03-22), currently available at

http://www.ams.org/tex/short-math-guide.html

1. Introduction This is a concise summary of recommended features in LATEX and a

couple of extension packages for writing math formulas. Readers needing greater depth

of detail are referred to the sources listed in the bibliography, especially [Lamport], [LUG],

[AMUG], [LFG], [LGG], and [LC]. A certain amount of familiarity with standard LATEX

terminology is assumed; if your memory needs refreshing on the LATEX meaning of command,

optional argument, environment, package, and so forth, see [Lamport].

The features described here are available to you if you use LATEX with two extension

packages published by the American Mathematical Society: amssymb and amsmath. Thus,

the source file for this document begins with

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{amssymb,amsmath}

The amssymb package might be omissible for documents whose math symbol usage is rela-

tively modest; the easiest way to test this is to leave out the amssymb reference and see if

any math symbols in the document produce ‘Undefined control sequence’ messages.

Many noteworthy features found in other packages are not covered here; see Section 10.

Regarding math symbols, please note especially that the list given here is not intended to be

comprehensive, but to illustrate such symbols as users will normally find already present in

their LATEX system and usable without installing any additional fonts or doing other setup

work.

If you have a need for a symbol not shown here, you will probably want to consult The

Comprehensive LATEX Symbols List (Pakin):

http://www.ctan.org/tex-archive/info/symbols/comprehensive/.

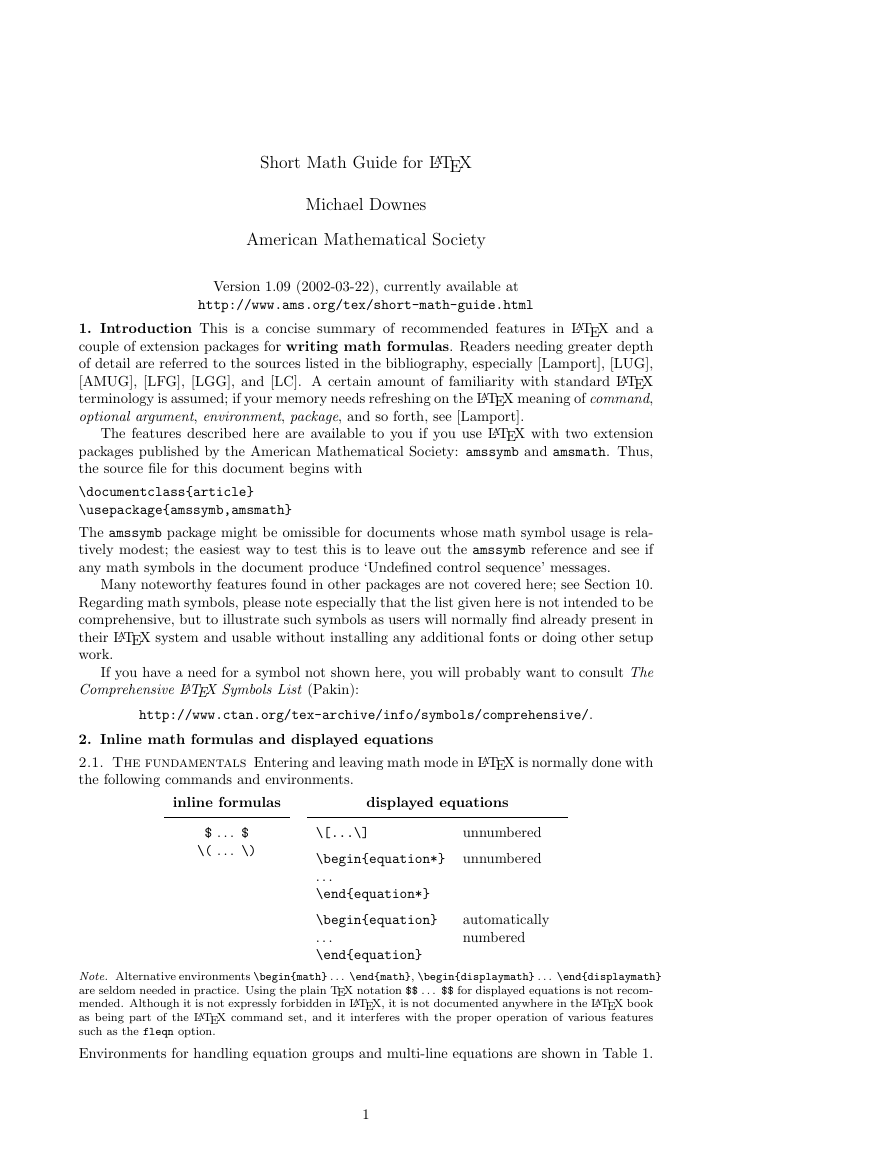

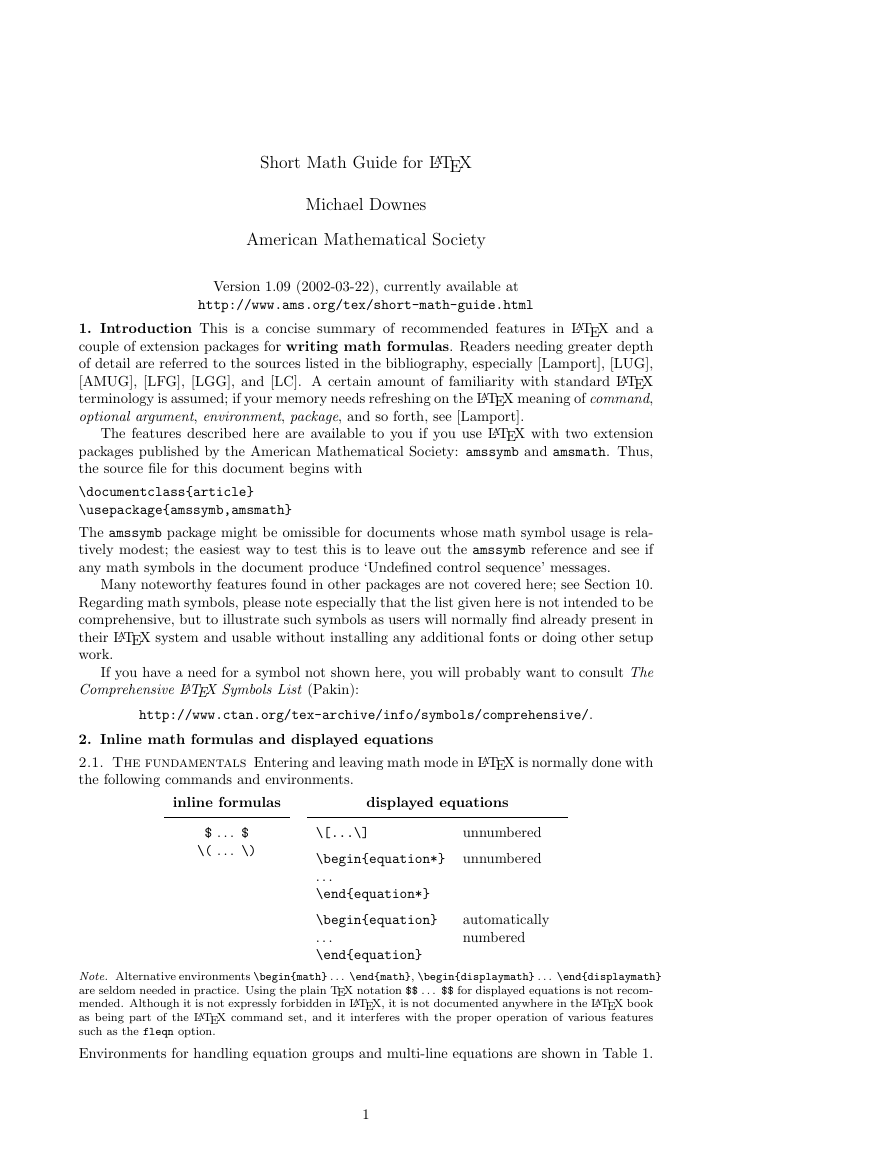

2. Inline math formulas and displayed equations

2.1. The fundamentals Entering and leaving math mode in LATEX is normally done with

the following commands and environments.

inline formulas

displayed equations

$ . . . $

\( . . . \)

\[...\]

\begin{equation*}

. . .

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation}

. . .

\end{equation}

unnumbered

unnumbered

automatically

numbered

Note. Alternative environments \begin{math} . . . \end{math}, \begin{displaymath} . . . \end{displaymath}

are seldom needed in practice. Using the plain TEX notation $$ . . . $$ for displayed equations is not recom-

mended. Although it is not expressly forbidden in LATEX, it is not documented anywhere in the LATEX book

as being part of the LATEX command set, and it interferes with the proper operation of various features

such as the fleqn option.

Environments for handling equation groups and multi-line equations are shown in Table 1.

1

�

Short Math Guide for LATEX, version 1.09 (2002-03-22)

2

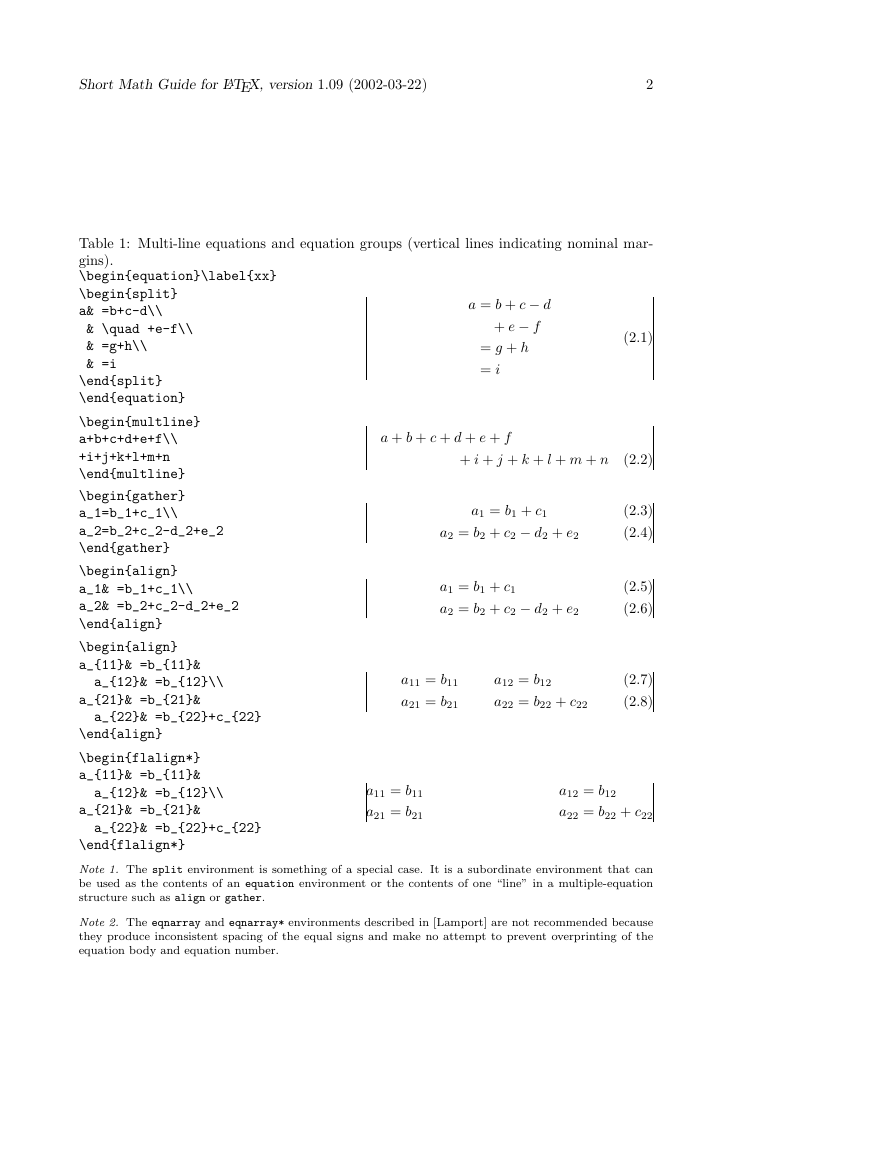

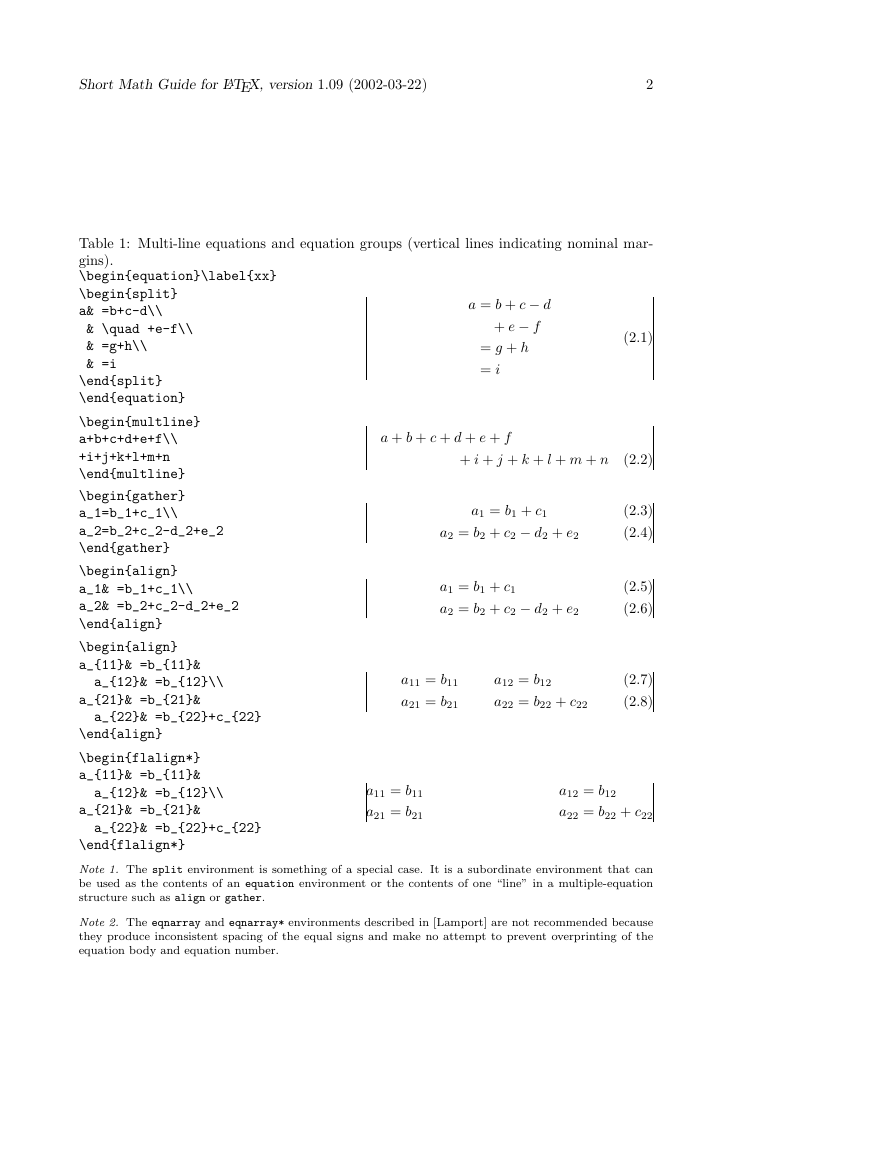

Table 1: Multi-line equations and equation groups (vertical lines indicating nominal mar-

gins).

\begin{equation}\label{xx}

\begin{split}

a& =b+c-d\\

& \quad +e-f\\

& =g+h\\

& =i

\end{split}

\end{equation}

\begin{multline}

a+b+c+d+e+f\\

+i+j+k+l+m+n

\end{multline}

\begin{gather}

a_1=b_1+c_1\\

a_2=b_2+c_2-d_2+e_2

\end{gather}

\begin{align}

a_1& =b_1+c_1\\

a_2& =b_2+c_2-d_2+e_2

\end{align}

\begin{align}

a_{11}& =b_{11}&

a_{12}& =b_{12}\\

a_{21}& =b_{21}&

a_{22}& =b_{22}+c_{22}

\end{align}

\begin{flalign*}

a_{11}& =b_{11}&

a_{12}& =b_{12}\\

a_{21}& =b_{21}&

a_{22}& =b_{22}+c_{22}

\end{flalign*}

a = b + c − d

+ e − f

= g + h

= i

(2.1)

a + b + c + d + e + f

+ i + j + k + l + m + n (2.2)

a1 = b1 + c1

a2 = b2 + c2 − d2 + e2

a1 = b1 + c1

a2 = b2 + c2 − d2 + e2

(2.3)

(2.4)

(2.5)

(2.6)

a11 = b11

a21 = b21

a12 = b12

a22 = b22 + c22

(2.7)

(2.8)

a11 = b11

a21 = b21

a12 = b12

a22 = b22 + c22

Note 1. The split environment is something of a special case. It is a subordinate environment that can

be used as the contents of an equation environment or the contents of one “line” in a multiple-equation

structure such as align or gather.

Note 2. The eqnarray and eqnarray* environments described in [Lamport] are not recommended because

they produce inconsistent spacing of the equal signs and make no attempt to prevent overprinting of the

equation body and equation number.

�

Short Math Guide for LATEX, version 1.09 (2002-03-22)

2.2. Automatic numbering and cross-referencing To get an auto-numbered equa-

tion, use the equation environment; to assign a label for cross-referencing, use the \label

command:

3

\begin{equation}\label{reio}

...

\end{equation}

To get a cross-reference to an auto-numbered equation, use the \eqref command:

... using equations \eqref{ax1} and \eqref{bz2}, we

can derive ...

The above example would produce something like

using equations (3.2) and (3.5), we can derive

In other words, \eqref{ax1} is equivalent to (\ref{ax1}).

To give your equation numbers the form m.n (section-number.equation-number), use

the \numberwithin command in the preamble of your document:

\numberwithin{equation}{section}

For more details on custom numbering schemes see [Lamport, §6.3, §C.8.4].

The subequations environment provides a convenient way to number equations in a

group with a subordinate numbering scheme. For example, supposing that the current

equation number is 2.1, write

\begin{equation}\label{first}

a=b+c

\end{equation}

some intervening text

\begin{subequations}\label{grp}

\begin{align}

a&=b+c\label{second}\\

d&=e+f+g\label{third}\\

h&=i+j\label{fourth}

\end{align}

\end{subequations}

to get

some intervening text

a = b + c

a = b + c

d = e + f + g

h = i + j

(2.9)

(2.10a)

(2.10b)

(2.10c)

By putting a \label command immediately after \begin{subequations} you can get a

reference to the parent number; \eqref{grp} from the above example would produce (2.10)

while \eqref{second} would produce (2.10a).

3. Math symbols and math fonts

3.1. Classes of math symbols The symbols in a math formula fall into different classes

that correspond more or less to the part of speech each symbol would have if the formula

were expressed in words. Certain spacing and positioning cues are traditionally used for

the different symbol classes to increase the readability of formulas.

�

Short Math Guide for LATEX, version 1.09 (2002-03-22)

4

Class

number Mnemonic

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Ord

Op

Bin

Rel

Open

Close

Pun

Examples

A 0 Φ ∞

P Q R

Description

(part of speech)

simple/ordinary (“noun”)

prefix operator

binary operator (conjunction) + ∪ ∧

= < ⊂

relation/comparison (verb)

( [ { h

left/opening delimiter

) ] } i

right/closing delimiter

postfix/punctuation

. , ; !

Note 1. The distinction in TEX between class 0 and an additional class 7 has to do only with font selection

issues and is immaterial here.

Note 2. Symbols of class Bin, notably the minus sign −, are automatically coerced to class 0 (no space) if

they do not have a suitable left operand.

The spacing for a few symbols follows tradition instead of the general rule: although /

is (semantically speaking) of class 2, we write k/2 with no space around the slash rather

than k / 2. And compare p|q p|q (no space) with p\mid q p | q (class-3 spacing).

The proper way to define a new math symbol is discussed in LATEX 2ε font selection

[LFG]. It is not really possible to give a useful synopsis here because one needs first to

understand the ramifications of font specifications.

3.2. Some symbols intentionally omitted here The following math symbols that

are mentioned in the LATEX book [Lamport] are intentionally omitted from this discussion

because they are superseded by equivalent symbols when the amssymb package is loaded.

If you are using the amssymb package anyway, the only thing that you are likely to gain by

using the alternate name is an unnecessary increase in the number of fonts used by your

document.

\Box, see \square

\Diamond, see \lozenge ♦

\leadsto, see \rightsquigarrow

\Join, see \bowtie ./

\lhd, see \vartriangleleft C

\unlhd, see \trianglelefteq E

\rhd, see \vartriangleright B

\unrhd, see \trianglerighteq D

Furthermore, there are many, many additional symbols available for LATEX use above

and beyond the ones included here. This list is not intended to be comprehensive. For a

much more comprehensive list of symbols, including nonmathematically oriented ones such

as phonetic alphabetic or dingbats, see The Comprehensive LATEX Symbols List (Pakin):

http://www.ctan.org/tex-archive/info/symbols/comprehensive/.

3.3. Latin letters and Arabic numerals The Latin letters are simple symbols, class 0.

The default font for them in math formulas is italic.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

When adding an accent to an i or j in math, dotless variants can be obtained with \imath

and \jmath:

ı \imath

\jmath

ˆ \hat{\jmath}

Arabic numerals 0–9 are also of class 0. Their default font is upright/roman.

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

�

Short Math Guide for LATEX, version 1.09 (2002-03-22)

3.4. Greek letters Like the Latin letters, the Greek letters are simple symbols, class 0.

For obscure historical reasons, the default font for lowercase Greek letters in math formu-

las is italic while the default font for capital Greek letters is upright/roman.

(In other

fields such as physics and chemistry, however, the typographical traditions are somewhat

different.) The capital Greek letters not present in this list are the letters that have the

same appearance as some Latin letter: A for Alpha, B for Beta, and so on. In the list of

lowercase letters there is no omicron because it would be identical in appearance to Latin o.

In practice, the Greek letters that have Latin look-alikes are seldom used in math formulas,

to avoid confusion.

5

Γ \Gamma

∆ \Delta

Λ \Lambda

Φ \Phi

Π \Pi

Ψ \Psi

Σ \Sigma

Θ \Theta

Υ \Upsilon

Ξ \Xi

Ω \Omega

α \alpha

β \beta

γ \gamma

δ \delta

� \epsilon

ζ \zeta

η \eta

θ \theta

ι \iota

κ \kappa

λ \lambda

µ \mu

ν \nu

ξ \xi

π \pi

ρ \rho

σ \sigma

τ \tau

υ \upsilon

φ \phi

χ \chi

ψ \psi

ω \omega

z \digamma

ε \varepsilon

κ \varkappa

ϕ \varphi

� \varpi

� \varrho

ς \varsigma

ϑ \vartheta

3.5. Other alphabetic symbols These are also class 0.

ℵ \aleph

� \hslash

f \mho

i \beth

k \daleth

∂ \partial

ג \gimel

℘ \wp

{ \complement

‘ \ell

ð \eth

� \hbar

s \circledS

k \Bbbk

‘ \Finv

a \Game

= \Im< \Re

3.6. Miscellaneous simple symbols These symbols are also of class 0 (ordinary) which

means they do not have any built-in spacing.

♣ \clubsuit

\diagdown

\diagup

♦ \diamondsuit

∅ \emptyset

∃ \exists

[ \flat

∀ \forall

♥ \heartsuit

∞ \infty

# \#

& \&

∠ \angle

8 \backprime

F \bigstar

\blacklozenge

\blacksquare

N \blacktriangle

H \blacktriangledown

⊥ \bot

Note 1. A common mistake in the use of the symbols and # is to try to make them serve as binary

operators or relation symbols without using a properly defined math symbol command. If you merely use

the existing commands \square or \# the inter-symbol spacing will be incorrect because those commands

produce a class-0 symbol.

Note 2. Synonyms: ¬ \lnot

\square

√

\surd

> \top

4 \triangle

O \triangledown

∅ \varnothing

♦ \lozenge

] \measuredangle

∇ \nabla

\ \natural

¬ \neg

@ \nexists

0 \prime

] \sharp

♠ \spadesuit

^ \sphericalangle

�

Short Math Guide for LATEX, version 1.09 (2002-03-22)

3.7. Binary operator symbols

∗ *

+ +− -q \amalg

· \cdot

\centerdot

◦ \circ

~ \circledast

} \circledcirc

\circleddash

∪ \cup

d \Cup

g \curlyvee

f \curlywedge

† \dagger

‡ \ddagger

\diamond

÷ \div

> \divideontimes

u \dotplus

[ \doublebarwedge

m \gtrdot

| \intercal

h \leftthreetimes

l \lessdot

n \ltimes

∓ \mp \odot

\ominus

⊕ \oplus

\oslash

⊗ \otimes

± \pm

i \rightthreetimes

o \rtimes

\ \setminus

∗ \ast

Z \barwedge

\bigcirc

5 \bigtriangledown

4 \bigtriangleup

\boxdot

\boxminus

\boxplus

\boxtimes

• \bullet

∩ \cap

e \Cap

Synonyms: ∧ \land, ∨ \lor, d \doublecup, e \doublecap

3.8. Relation symbols: < = > ∼ and variants

5 \leqq

6 \leqslant

/ \lessapprox

Q \lesseqgtr

S \lesseqqgtr

≶ \lessgtr

. \lesssim

\ll

≪ \lll

\lnapprox

\lneq

\lneqq

\lnsim

\lvertneqq

\ncong

6= \neq

\ngeq

\ngeqq

\ngeqslant

0 \eqslantless

≡ \equiv

; \fallingdotseq

≥ \geq

= \geqq

> \geqslant

\gg

≫ \ggg

\gnapprox

\gneq

\gneqq

\gnsim

’ \gtrapprox

R \gtreqless

T \gtreqqless

≷ \gtrless

& \gtrsim

\gvertneqq

≤ \leq

< <

= =

> >

≈ \approx

u \approxeq

\asymp

v \backsim

w \backsimeq

l \bumpeq

m \Bumpeq

$ \circeq

∼= \cong

2 \curlyeqprec

3 \curlyeqsucc

.= \doteq

+ \doteqdot

P \eqcirc

h \eqsim

1 \eqslantgtr

Synonyms:

6= \ne, ≤ \le, ≥ \ge, + \Doteq, ≪ \llless, ≫ \gggtr

6

r \smallsetminus

u \sqcap

t \sqcup

? \star

× \times

/ \triangleleft

. \triangleright

] \uplus

∨ \vee

Y \veebar

∧ \wedge

o \wr

∼ \sim

’ \simeq

\succ

v \succapprox

< \succcurlyeq

\succeq

\succnapprox

\succneqq

\succnsim

% \succsim

≈ \thickapprox

∼ \thicksim

, \triangleq

≯ \ngtr

\nleq

\nleqq

\nleqslant

≮ \nless

⊀ \nprec

\npreceq

\nsim

\nsucc

\nsucceq

≺ \prec

w \precapprox

4 \preccurlyeq

\preceq

\precnapprox

\precneqq

\precnsim

- \precsim

: \risingdotseq

�

Short Math Guide for LATEX, version 1.09 (2002-03-22)

3.9. Relation symbols: arrows See also Section 4.

\circlearrowleft

W \Lleftarrow

←− \longleftarrow

\circlearrowright

⇐= \Longleftarrow

x \curvearrowleft

←→ \longleftrightarrow

y \curvearrowright

⇐⇒ \Longleftrightarrow

\downdownarrows

7−→ \longmapsto

\downharpoonleft

−→ \longrightarrow

\downharpoonright

←- \hookleftarrow

=⇒ \Longrightarrow

,→ \hookrightarrow

" \looparrowleft

← \leftarrow

# \looparrowright

⇐ \Leftarrow

\Lsh

7→ \mapsto

\leftarrowtail

( \multimap

) \leftharpoondown

: \nLeftarrow

( \leftharpoonup

⇔ \leftleftarrows

< \nLeftrightarrow

↔ \leftrightarrow

; \nRightarrow

⇔ \Leftrightarrow

% \nearrow

\leftrightarrows

8 \nleftarrow

\leftrightharpoons

= \nleftrightarrow

! \leftrightsquigarrow

9 \nrightarrow

Synonyms: ← \gets, → \to, \restriction

3.10. Relation symbols: miscellaneous

7

- \nwarrow

→ \rightarrow

⇒ \Rightarrow

\rightarrowtail

+ \rightharpoondown

* \rightharpoonup

\rightleftarrows

\rightleftharpoons

⇒ \rightrightarrows

\rightsquigarrow

V \Rrightarrow

\Rsh& \searrow

. \swarrow

\twoheadleftarrow

\twoheadrightarrow

\upharpoonleft

\upharpoonright

\upuparrows

\backepsilon

∵ \because

G \between

J \blacktriangleleft

I \blacktriangleright

./ \bowtie

a \dashv

_ \frown

∈ \in

| \mid

|= \models

3 \ni

- \nmid

/∈ \notin

∦ \nparallel

. \nshortmid

/ \nshortparallel

* \nsubseteq

Synonyms: 3 \owns

" \nsubseteqq

+ \nsupseteq

# \nsupseteqq

6 \ntriangleleft

5 \ntrianglelefteq

7 \ntriangleright

4 \ntrianglerighteq

0 \nvdash

1 \nVdash

2 \nvDash

3 \nVDash

k \parallel

⊥ \perp

t \pitchfork

∝ \propto

p \shortmid

q \shortparallel

a \smallfrown

‘ \smallsmile

^ \smile

@ \sqsubset

v \sqsubseteq

A \sqsupset

w \sqsupseteq

⊂ \subset

b \Subset

⊆ \subseteq

j \subseteqq

( \subsetneq

$ \subsetneqq

⊃ \supset

c \Supset

⊇ \supseteq

k \supseteqq

) \supsetneq

% \supsetneqq

∴ \therefore

E \trianglelefteq

D \trianglerighteq

∝ \varpropto

\varsubsetneq

& \varsubsetneqq

! \varsupsetneq

’ \varsupsetneqq

M \vartriangle

C \vartriangleleft

B \vartriangleright

‘ \vdash

\Vdash

\vDash

\Vvdash

3.11. Cumulative (variable-size) operators

R \int

H \oint

T \bigcap

S \bigcup

J \bigodot

L \bigoplus

N \bigotimes

F \bigsqcup

U \biguplus

W \bigvee

V \bigwedge

‘ \coprod

Q \prod

P \sum

∫ \smallint

�

Short Math Guide for LATEX, version 1.09 (2002-03-22)

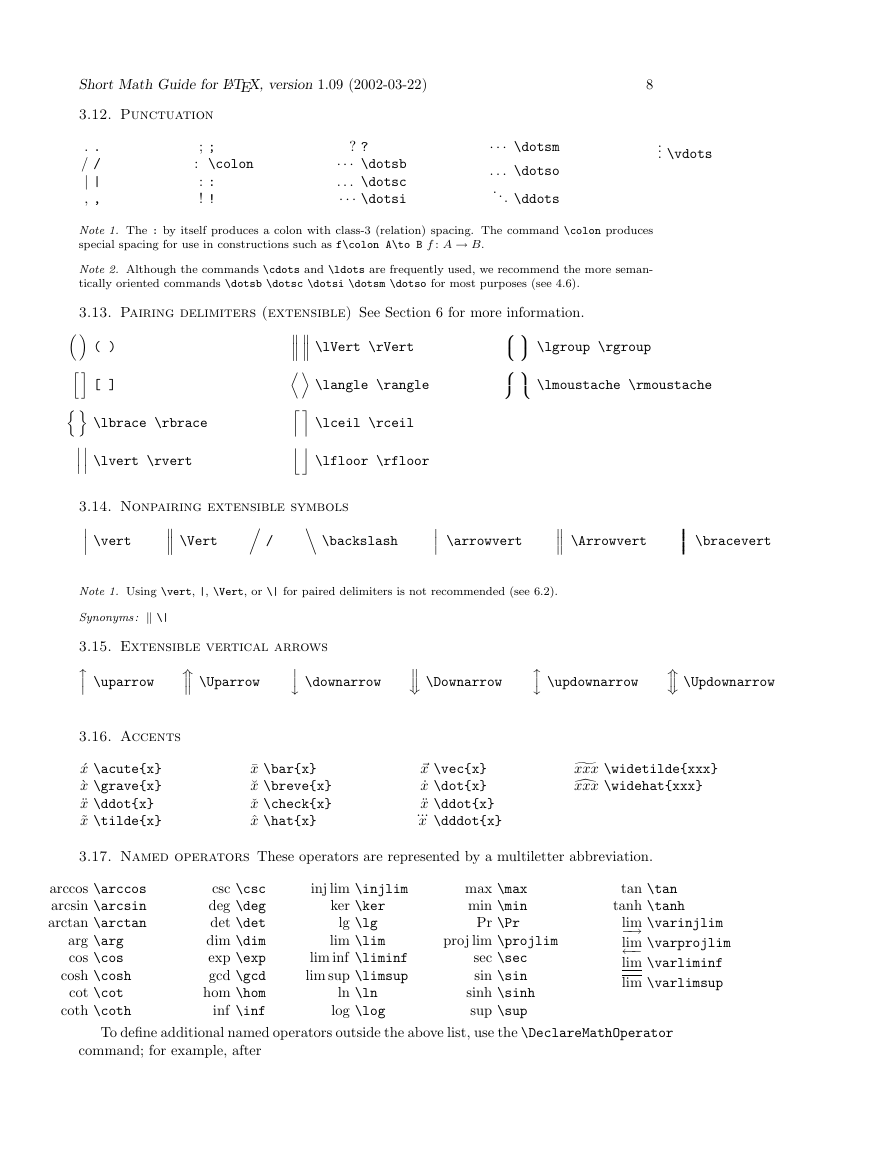

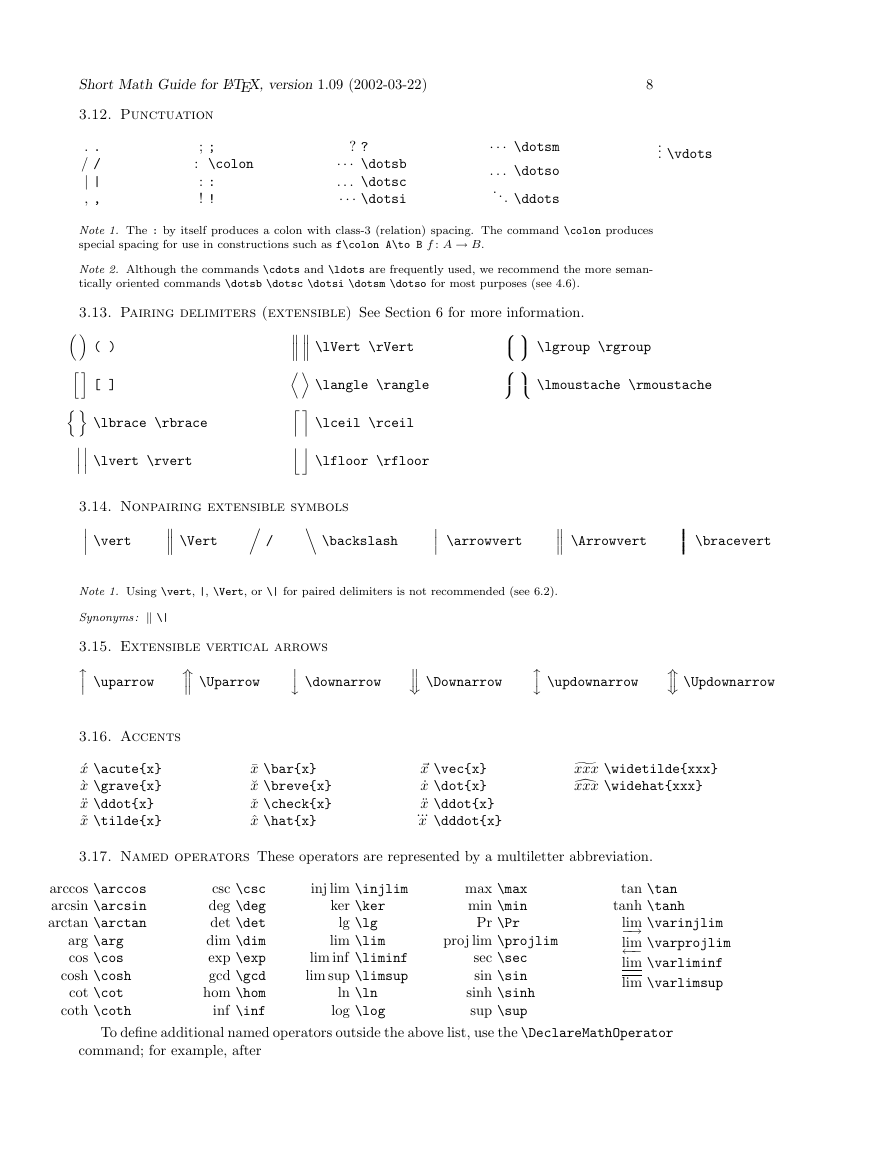

3.12. Punctuation

. .

/ /| |

, ,

; ;

: \colon

: :

! !

? ?

··· \dotsb

. . . \dotsc

··· \dotsi

··· \dotsm

. . . \dotso

... \ddots

8

... \vdots

Note 1. The : by itself produces a colon with class-3 (relation) spacing. The command \colon produces

special spacing for use in constructions such as f\colon A\to B f : A → B.

Note 2. Although the commands \cdots and \ldots are frequently used, we recommend the more seman-

tically oriented commands \dotsb \dotsc \dotsi \dotsm \dotso for most purposes (see 4.6).

3.13. Pairing delimiters (extensible) See Section 6 for more information.

\lgroup \rgroup

\lmoustache \rmoustache

[ ]

( )

hi

no

\lvert \rvert

\Vert

\vert

\lbrace \rbrace

\langle \rangle

\lVert \rVert

DE

lm

jk

/

\lceil \rceil

\backslash

\lfloor \rfloor

.

/

3.14. Nonpairing extensible symbols

\arrowvert

www \Arrowvert

\bracevert

Note 1. Using \vert, |, \Vert, or \| for paired delimiters is not recommended (see 6.2).

Synonyms: k \|

3.15. Extensible vertical arrows

x \uparrow

~ww \Uparrow

y \downarrow

ww \Downarrow

xy \updownarrow

~w \Updownarrow

3.16. Accents

´x \acute{x}

`x \grave{x}

¨x \ddot{x}

˜x \tilde{x}

¯x \bar{x}

˘x \breve{x}

ˇx \check{x}

ˆx \hat{x}

~x \vec{x}

˙x \dot{x}

¨x \ddot{x}

...

x \dddot{x}

gxxx \widetilde{xxx}

dxxx \widehat{xxx}

3.17. Named operators These operators are represented by a multiletter abbreviation.

arccos \arccos

arcsin \arcsin

arctan \arctan

arg \arg

cos \cos

cosh \cosh

cot \cot

coth \coth

csc \csc

deg \deg

det \det

dim \dim

exp \exp

gcd \gcd

hom \hom

inf \inf

inj lim \injlim

ker \ker

lg \lg

lim \lim

lim inf \liminf

lim sup \limsup

ln \ln

log \log

proj lim \projlim

max \max

min \min

Pr \Pr

sec \sec

sin \sin

sinh \sinh

sup \sup

tan \tan

tanh \tanh

lim−→ \varinjlim

lim←− \varprojlim

lim \varliminf

lim \varlimsup

To define additional named operators outside the above list, use the \DeclareMathOperator

command; for example, after

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc