CS 61B: Lecture 1

Wednesday, January 22, 2014

Prof. Jonathan Shewchuk, jrs@cory.eecs

Email to prof & all TAs at once (preferred): cs61b@cory.eecs

Today's reading: Sierra & Bates, pp. 1-9, 18-19, 84.

Handout: Course Overview (also available from CS 61B Web page)

Also, read the CS 61B Web page as soon as possible!

>>> http://www.cs.berkeley.edu/~jrs/61b <<<

YOU are responsible for keeping up with readings & assignments. Few reminders.

The Piazza board is required reading: piazza.com/berkeley/spring2014/cs61b

Labs

----

Labs (in 271, 273, 275, 330 Soda) start Thursday. Discussion sections start

Monday. You must attend your scheduled lab (as assigned by Telebears) to

1) get an account (needed for Lab 1 and Homework 1), and

2) login to turn on your ability to turn in homework (takes up to 24 hours).

You may only attend the lab in which you are officially enrolled. If you are

not enrolled in a lab (on the waiting list or in concurrent enrollment), you

must attend a lab that has space. (Show up and ask the TA if there's room for

you.)

You will not be enrolled in the course until you are enrolled in a lab. If

you're on the waiting list and the lab you want is full, you can change to one

that isn't, or you can stay on the waitlist and hope somebody drops.

If you're not yet enrolled in a lab, just keep going to them until you find one

that has room for you (that week). Once you get enrolled in a lab, though,

please always attend the one you're enrolled in.

Prerequisites

-------------

Ideally, you have taken CS 61A or E 7, or at least you're taking one of them

this semester. If not, you might get away with it, but if you have not

mastered recursion, expect to have a very hard time in this class. If you've

taken a data structures course before, you might be able to skip CS 61B. See

the Course Overview and Brian Harvey (781 Soda) for details.

Textbooks

---------

Kathy Sierra and Bert Bates, Head First Java, Second Edition, O'Reilly, 2005.

ISBN # 0-596-00920-8. (The first edition is just as good.)

Michael T. Goodrich and Roberto Tamassia, Data Structures and Algorithms in

Java, Fifth Edition, John Wiley & Sons, 2010. ISBN # 0-470-38326-7.

(The first/third/fourth/sixth edition is just as good, but not the second.)

We will use Sierra/Bates for the first month. Lay your hands on a copy as soon

as possible.

Buy the CS 61B class reader at Vick Copy, 1879 Euclid. The bulk of the reader

is old CS 61B exams, which will not be provided online. The front of the

reader is stuff you'll want to have handy when you're in lab, hacking.

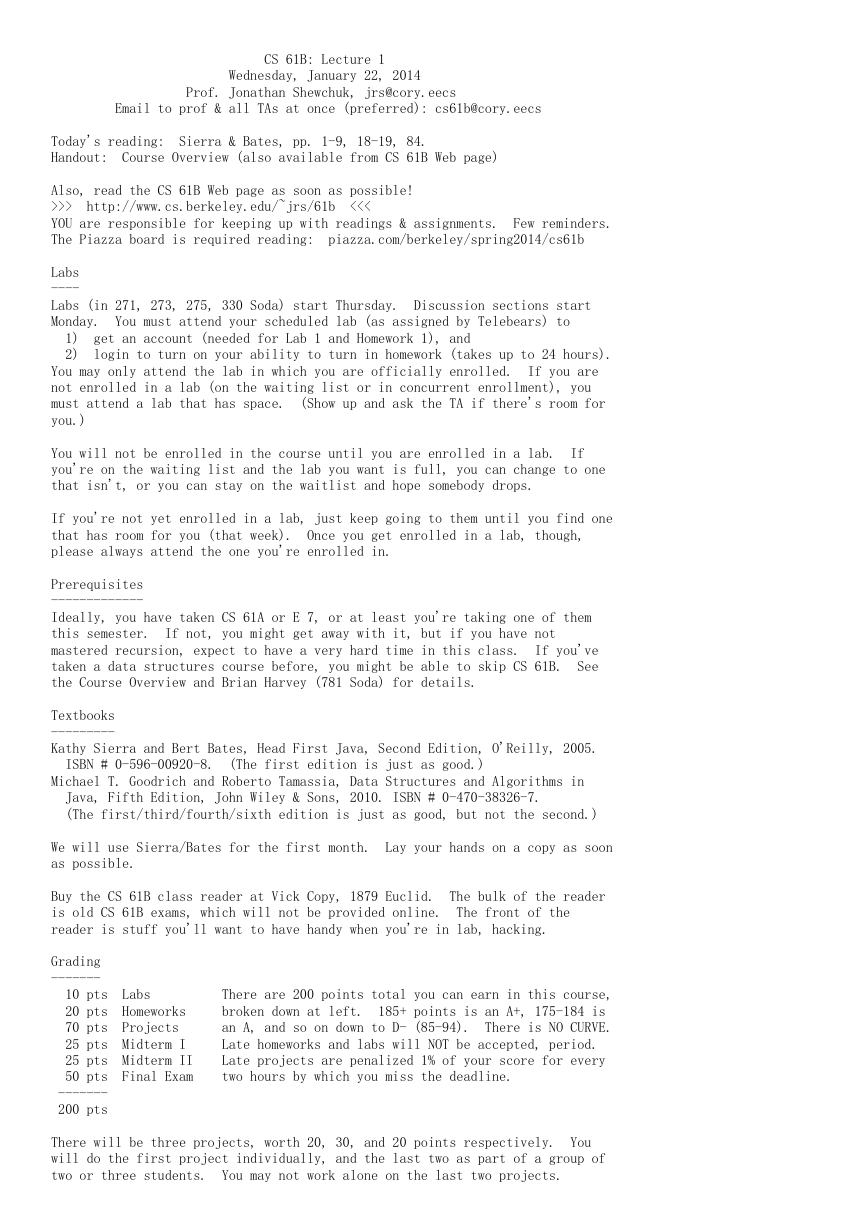

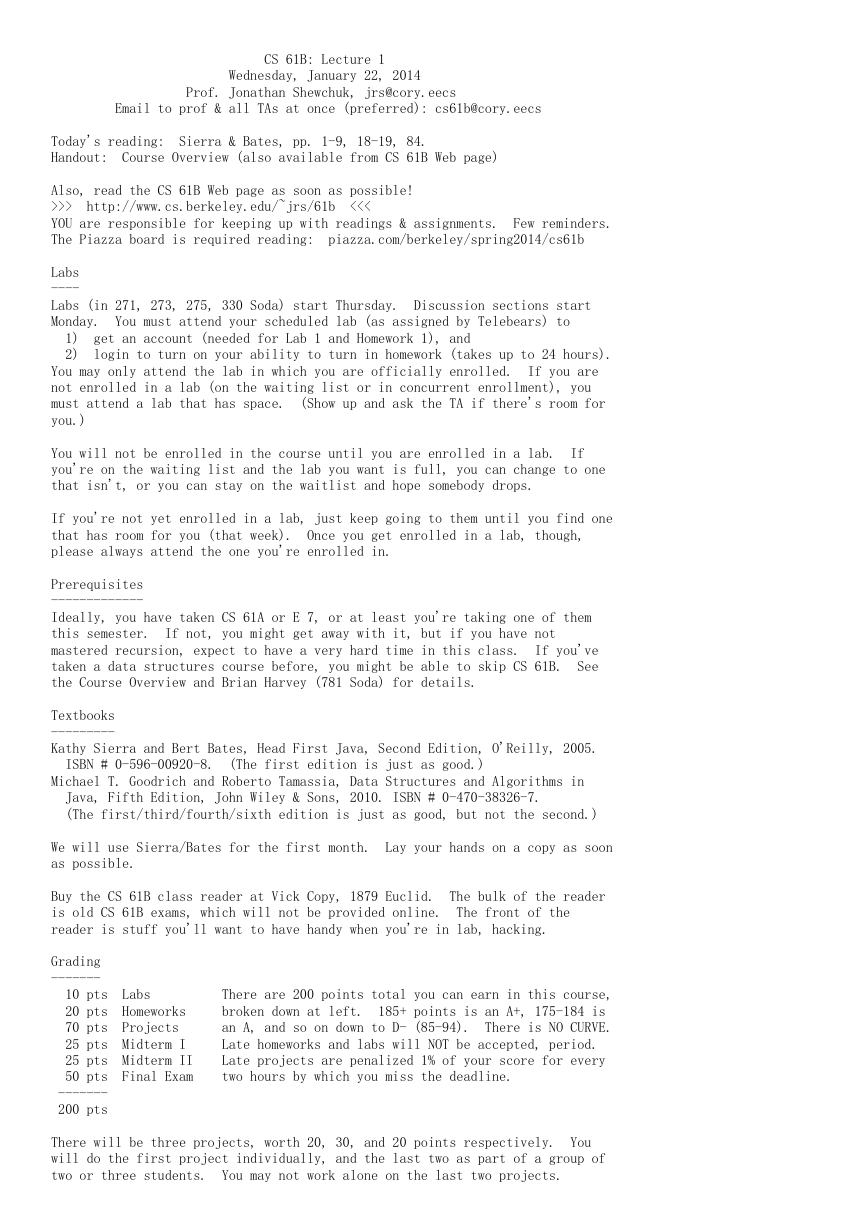

Grading

-------

10 pts Labs There are 200 points total you can earn in this course,

20 pts Homeworks broken down at left. 185+ points is an A+, 175-184 is

70 pts Projects an A, and so on down to D- (85-94). There is NO CURVE.

25 pts Midterm I Late homeworks and labs will NOT be accepted, period.

25 pts Midterm II Late projects are penalized 1% of your score for every

50 pts Final Exam two hours by which you miss the deadline.

-------

200 pts

There will be three projects, worth 20, 30, and 20 points respectively. You

will do the first project individually, and the last two as part of a group of

two or three students. You may not work alone on the last two projects.

�

All homeworks and projects will be turned in electronically.

Cheating

--------

...will be reported to the Office of Student Conduct.

1) "No Code Rule": Never have a copy of someone else's program in your

possession and never give your program to someone else.

2) Discussing an assignment without sharing any code is generally okay.

Helping someone to interpret a compiler error message is an example of

permissible collaboration. However, if you get a significant idea from

someone, acknowledge them in your assignment.

3) These rules apply to homeworks and projects. No discussion whatsoever in

exams, of course.

4) In group projects, you share code freely within your team, but not between

teams.

Goals of CS 61B

---------------

1) Learning efficient data structures and algorithms that use them.

2) Designing and writing large programs.

3) Understanding and designing data abstraction and interfaces.

4) Learning Java.

THE LANGUAGE OF OBJECT-ORIENTED PROGRAMMING

===========================================

Object: An object is a repository of data. For example, if MyList is a

ShoppingList object, MyList might record your shopping list.

Class: A class is a type of object. Many objects of the same class might

exist; for instance, MyList and YourList may both be ShoppingList objects.

Method: A procedure or function that operates on an object or a class.

A method is associated with a particular class. For instance, addItem might

be a method that adds an item to any ShoppingList object. Sometimes a method

is associated with a family of classes. For instance, addItem might operate

on any List, of which a ShoppingList is just one type.

Inheritance: A class may inherit properties from a more general class. For

example, the ShoppingList class inherits from the List class the property of

storing a sequence of items.

Polymorphism: The ability to have one method call work on several different

classes of objects, even if those classes need different implementations of

the method call. For example, one line of code might be able to call the

"addItem" method on _every_ kind of List, even though adding an item to a

ShoppingList is completely different from adding an item to a ShoppingCart.

Object-Oriented: Each object knows its own class and which methods manipulate

objects in that class. Each ShoppingList and each ShoppingCart knows which

implementation of addItem applies to it.

In this list, the one thing that truly distinguishes object-oriented languages

from procedural languages (C, Fortran, Basic, Pascal) is polymorphism.

Java

----

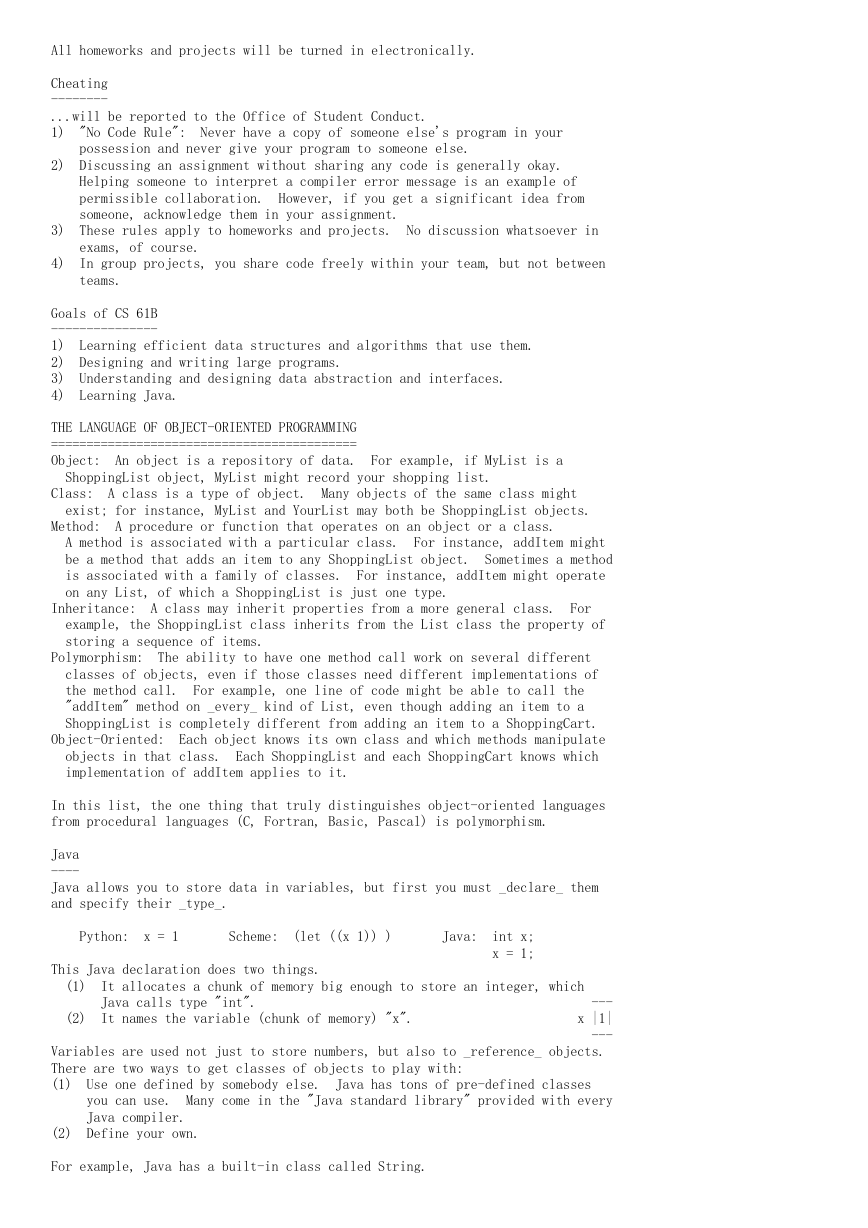

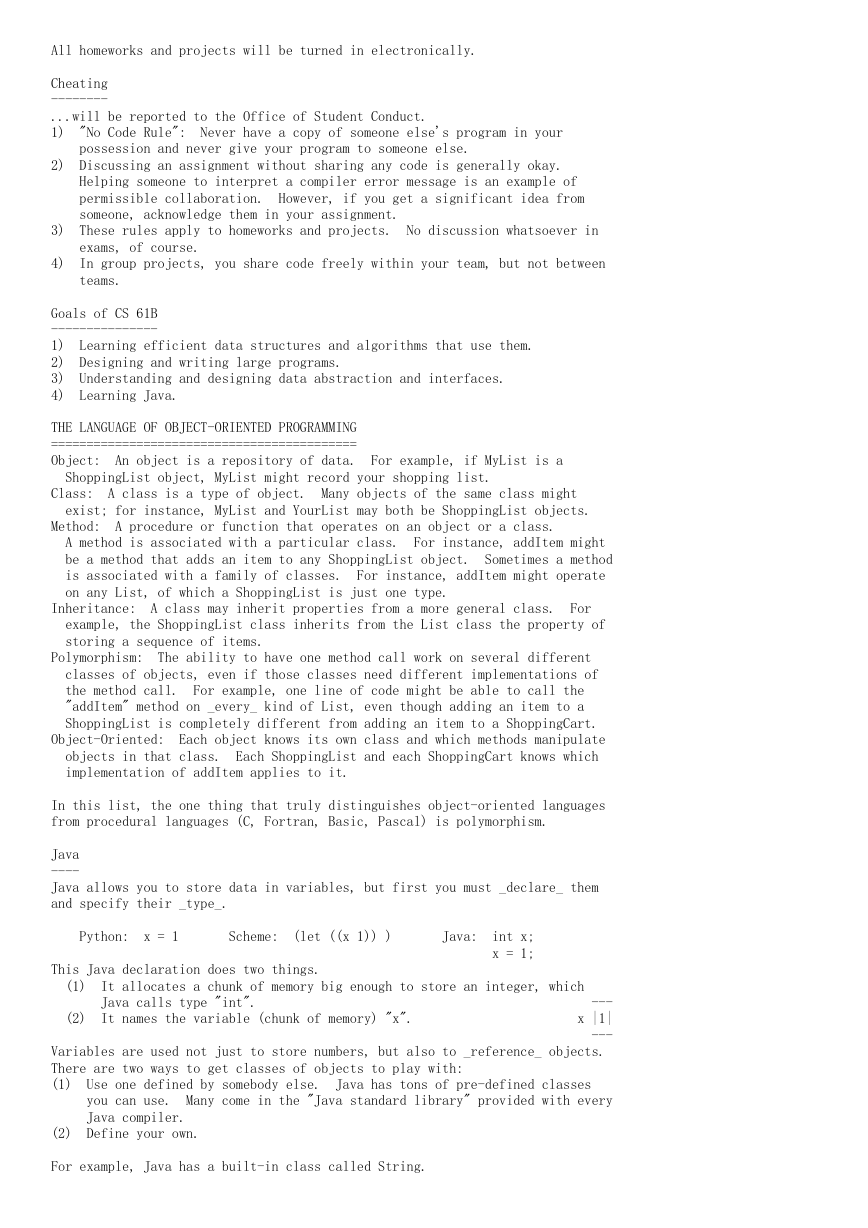

Java allows you to store data in variables, but first you must _declare_ them

and specify their _type_.

Python: x = 1 Scheme: (let ((x 1)) ) Java: int x;

x = 1;

This Java declaration does two things.

(1) It allocates a chunk of memory big enough to store an integer, which

Java calls type "int". ---

(2) It names the variable (chunk of memory) "x". x |1|

---

Variables are used not just to store numbers, but also to _reference_ objects.

There are two ways to get classes of objects to play with:

(1) Use one defined by somebody else. Java has tons of pre-defined classes

you can use. Many come in the "Java standard library" provided with every

Java compiler.

(2) Define your own.

For example, Java has a built-in class called String.

�

String myString;

This does _not_ create a String object. Instead, it declares a variable (chunk

of memory) that can store a _reference_ to a String object. I draw it as a

box.

---

myString | | <-- This box is a variable (not an object).

---

Initially, myString doesn't reference anything. You can make it reference a

String object by writing an assignment statement. But how do we get ahold of

an actual String object? You can create one.

myString = new String();

This line performs two distinct steps. First, the phrase "new String()" is

called a _constructor_. It constructs a brand new String object. Second, the

assignment "=" causes myString to _reference_ the object. You can think of

this as myString pointing to the object.

--- ------

myString |.+---->| | a String object

--- ------

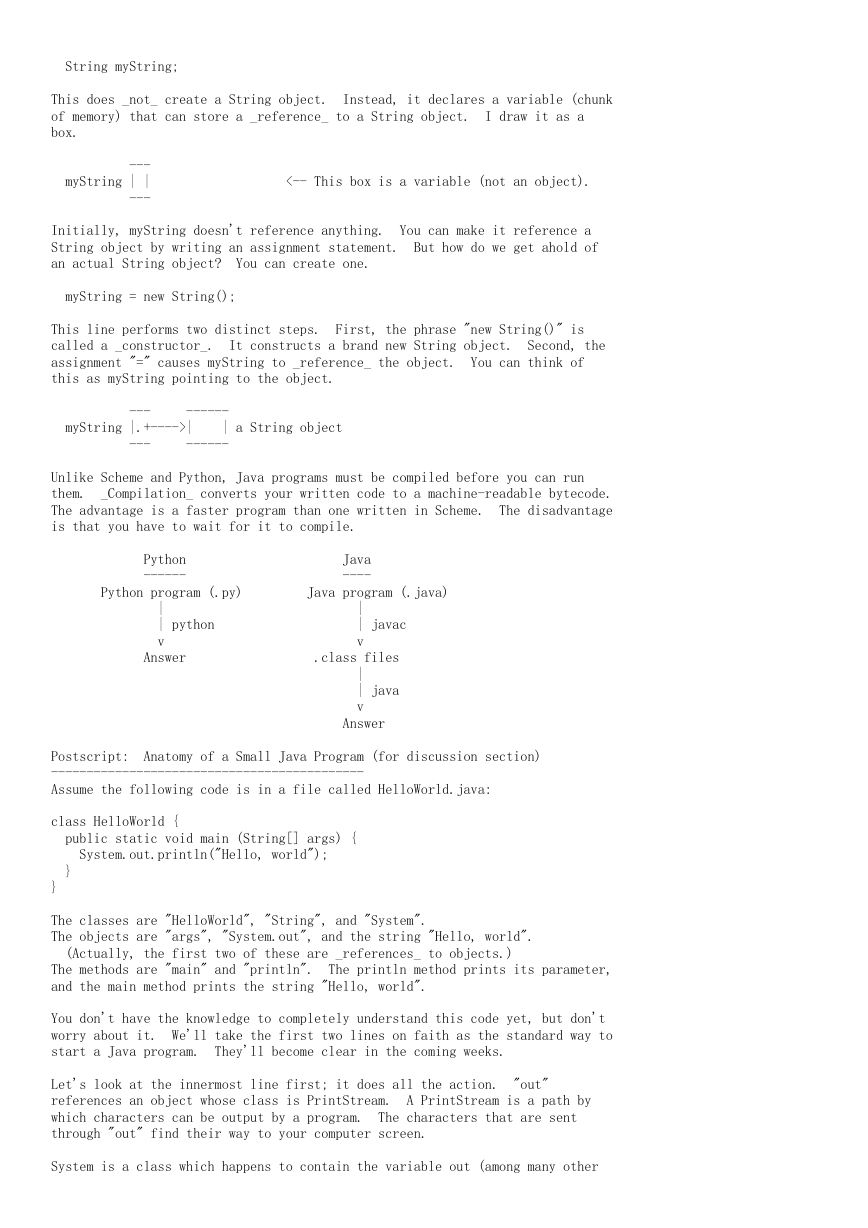

Unlike Scheme and Python, Java programs must be compiled before you can run

them. _Compilation_ converts your written code to a machine-readable bytecode.

The advantage is a faster program than one written in Scheme. The disadvantage

is that you have to wait for it to compile.

Python Java

------ ----

Python program (.py) Java program (.java)

| |

| python | javac

v v

Answer .class files

|

| java

v

Answer

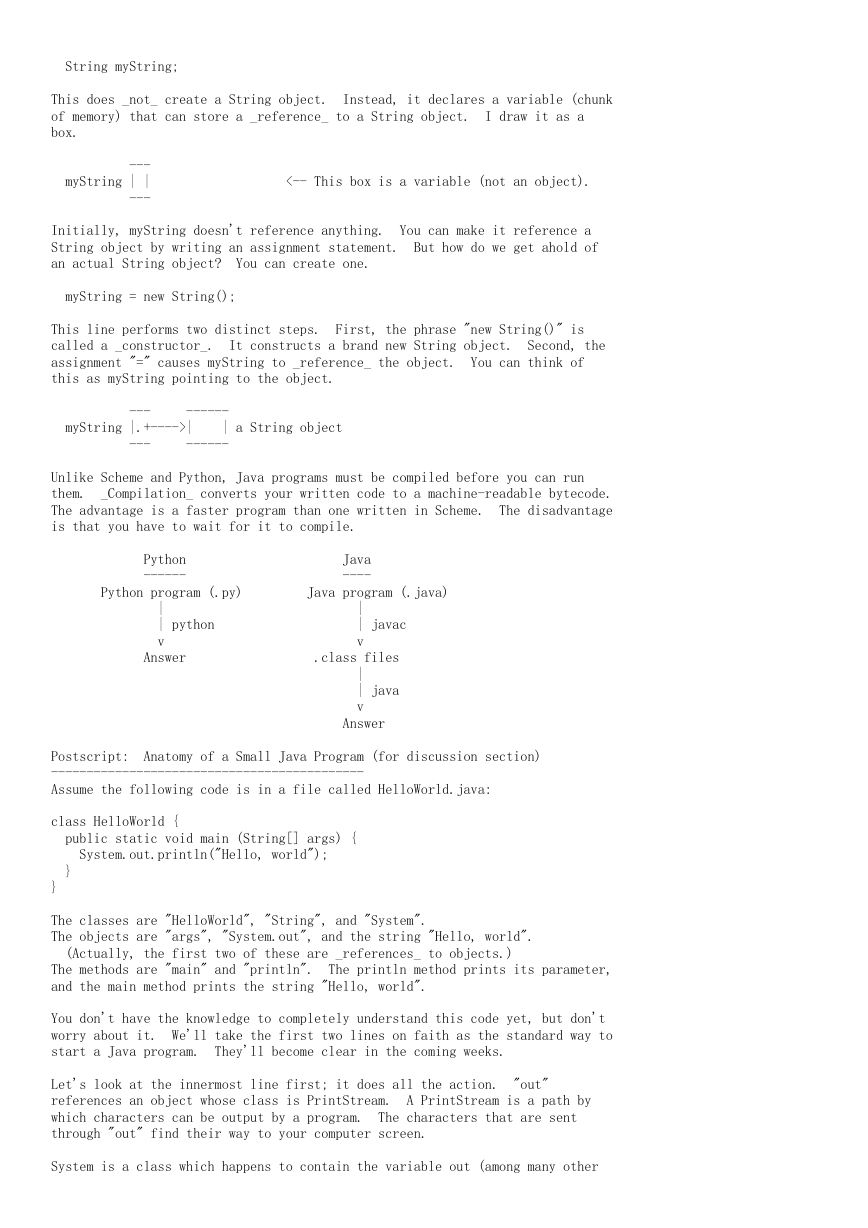

Postscript: Anatomy of a Small Java Program (for discussion section)

--------------------------------------------

Assume the following code is in a file called HelloWorld.java:

class HelloWorld {

public static void main (String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello, world");

}

}

The classes are "HelloWorld", "String", and "System".

The objects are "args", "System.out", and the string "Hello, world".

(Actually, the first two of these are _references_ to objects.)

The methods are "main" and "println". The println method prints its parameter,

and the main method prints the string "Hello, world".

You don't have the knowledge to completely understand this code yet, but don't

worry about it. We'll take the first two lines on faith as the standard way to

start a Java program. They'll become clear in the coming weeks.

Let's look at the innermost line first; it does all the action. "out"

references an object whose class is PrintStream. A PrintStream is a path by

which characters can be output by a program. The characters that are sent

through "out" find their way to your computer screen.

System is a class which happens to contain the variable out (among many other

�

variables). We have to write "System.out" to address the output stream,

because other classes might have variables called "out" too, with their own

meanings.

"println" is a method (procedure) of the class PrintStream. Hence, we can

invoke "println" from any PrintStream object, including System.out. "println"

takes one parameter, which can be a string.

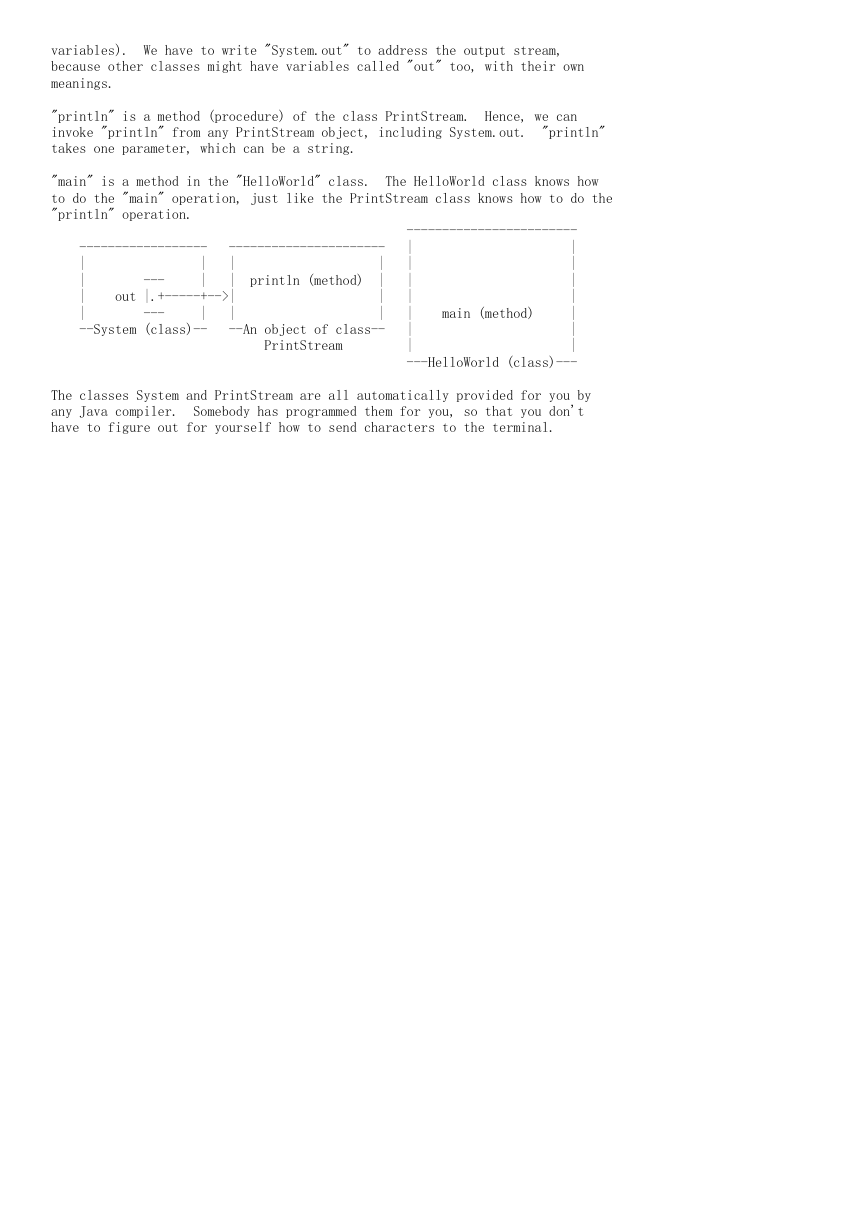

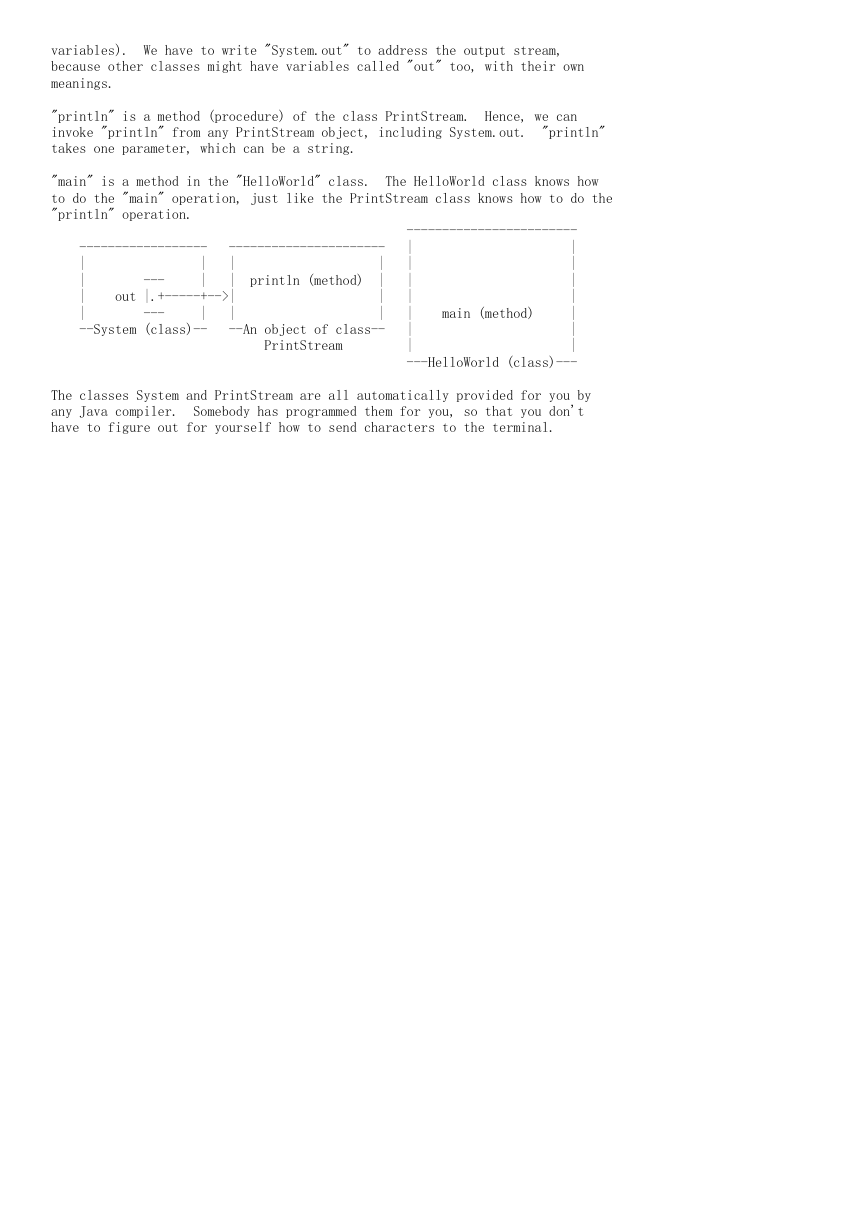

"main" is a method in the "HelloWorld" class. The HelloWorld class knows how

to do the "main" operation, just like the PrintStream class knows how to do the

"println" operation.

------------------------

------------------ ---------------------- | |

| | | | | |

| --- | | println (method) | | |

| out |.+-----+-->| | | |

| --- | | | | main (method) |

--System (class)-- --An object of class-- | |

PrintStream | |

---HelloWorld (class)---

The classes System and PrintStream are all automatically provided for you by

any Java compiler. Somebody has programmed them for you, so that you don't

have to figure out for yourself how to send characters to the terminal.

�

CS 61B: Lecture 2

Friday, January 24, 2014

Today's reading: Sierra & Bates, Chapter 2; pp. 54-58, 154-160, 661, 669.

OBJECTS AND CONSTRUCTORS

========================

String s; // Step 1: declare a String variable.

s = new String(); // Steps 2, 3: construct new empty String; assign it to s.

At this point, s is a variable that --- ------

references an "empty" String, i.e. s |.+---->| |

a String containing zero characters. --- ------

String s = new String(); // Steps 1, 2, 3 combined.

s = "Yow!"; // Construct a new String; make s a reference to it.

--- ----------

s |.+---->| Yow! |

--- ----------

String s2 = s; // Copy the reference stored in s into s2.

--- ---------- ---

s |.+---->| Yow! |<----+.| s2

--- ---------- ---

Now s and s2 reference the same object.

s2 = new String(s); // Construct a copy of object; store reference in s2.

--- ---------- --- ----------

s |.+---->| Yow! | s2 |.+---->| Yow! |

--- ---------- --- ----------

Now they refer to two different, but identical, objects.

Think about that. When Java executes that line, it does the following things,

in the following order.

- Java looks inside the variable s to see where it's pointing.

- Java follows the pointer to the String object.

- Java reads the characters stored in that String object.

- Java creates a new String object that stores a copy of those characters.

- Java stores a reference to the new String object in s2.

We've seen three String constructors:

(1) new String() constructs an _empty_string_--it's a string, but it

contains zero characters.

(2) "Yow!" constructs a string containing the characters Yow!.

(3) new String(s) takes a _parameter_ s. Then it makes a copy of the object

that s references.

Constructors _always_ have the same name as their class, except the special

constructor "stuffinquotes". That's the only exception.

Observe that "new String()" can take no parameters, or one parameter. These

are two different constructors--one that is called by "new String()", and one

that is called by "new String(s)". (Actually, there are many more than

two--check out the online Java API to see all the possibilities.)

METHODS

=======

Let's look at some methods that aren't constructors.

s2 = s.toUppercase(); // Create a string like s, but in all upper case.

--- ----------

s2 |.+---->| YOW! |

�

--- ----------

String s3 = s2.concat("!!"); // Also written: s3 = s2 + "!!";

--- ------------

s3 |.+---->| YOW!!! |

--- ------------

String s4 = "*".concat(s2).concat("*"); // Also written: s4 = "*" + s + "*";

--- ------------

s4 |.+---->| *YOW!* |

--- ------------

Now, here's an important fact: when Java executed the line

s2 = s.toUppercase();

the String object "Yow!" did _not_ change. Instead, s2 itself changed to

reference a new object. Java wrote a new "pointer" into the variable s2, so

now s2 points to a different object than it did before.

Unlike in C, in Java Strings are _immutable_--once they've been constructed,

their contents never change. If you want to change a String object, you've got

to create a brand new String object that reflects the changes you want. This

is not true of all objects; most Java objects let you change their contents.

You might find it confusing that methods like "toUppercase" and "concat" return

newly created String objects, though they are not constructors. The trick is

that those methods calls constructors internally, and return the newly

constructed Strings.

I/O Classes and Objects in Java

-------------------------------

Here are some objects in the System class for interacting with a user:

System.out is a PrintStream object that outputs to the screen.

System.in is an InputStream object that reads from the keyboard.

[Reminder: this is shorthand for "System.in is a variable that references

an InputStream object."]

But System.in doesn't have methods to read a line directly. There is a method

called readLine that does, but it is defined on BufferedReader objects.

- How do we construct a BufferedReader? One way is with an InputStreamReader.

- How do we construct an InputStreamReader? We need an InputStream.

- How do we construct an InputStream? System.in is one.

(You can figure all of this out by looking at the constructors in the online

Java libraries API--specifically, in the java.io library.)

Why all this fuss?

InputStream objects (like System.in) read raw data from some source (like the

keyboard), but don't format the data.

InputStreamReader objects compose the raw data into characters (which are

typically two bytes long in Java).

BufferedReader objects compose the characters into entire lines of text.

Why are these tasks divided among three different classes? So that any one

task can be reimplemented (say, for improved speed) without changing the other

two.

Here's a complete Java program that reads a line from the keyboard and prints

it on the screen.

import java.io.*;

�

class SimpleIO {

public static void main(String[] arg) throws Exception {

BufferedReader keybd =

new BufferedReader(new InputStreamReader(System.in));

System.out.println(keybd.readLine());

}

}

Don't worry if you don't understand the first three lines; we'll learn the

underlying ideas eventually. The first line is present because to use the Java

libraries, other than java.lang, you need to "import" them. java.io includes

the InputStreamReader and BufferedReader classes.

The second line just gives the program a name, "SimpleIO".

The third line is present because any Java program always begins execution at a

method named "main", which is usually defined more or less as above. When you

write a Java program, just copy the line of code, and plan to understand it a

few weeks from now.

Classes for Web Access

----------------------

Let's say we want to read a line of text from the White House Web page. (The

line will be HTML, which looks ugly. You don't need to understand HTML.)

How to read a line of text? With readLine on BufferedReader.

How to create a BufferedReader? With an InputStreamReader.

How to create a InputStreamReader? With an InputStream.

How to create an InputStream? With a URL.

import java.net.*;

import java.io.*;

class WHWWW {

public static void main(String[] arg) throws Exception {

URL u = new URL("http://www.whitehouse.gov/");

InputStream ins = u.openStream();

InputStreamReader isr = new InputStreamReader(ins);

BufferedReader whiteHouse = new BufferedReader(isr);

System.out.println(whiteHouse.readLine());

}

}

Postscript: Object-Oriented Terminology (not examinable)

----------------------------------------

In the words of Turing Award winner Nicklaus Wirth, "Object-oriented

programming (OOP) solidly rests on the principles and concepts of traditional

procedural programming. OOP has not added a single novel concept ... along

with the OOP paradigm came an entirely new terminology with the purpose of

mystifying the roots of OOP." Here's a translation guide.

Procedural Programming Object-Oriented Programming

---------------------- ---------------------------

record / structure object

record type class

extending a type declaring a subclass

procedure method

procedure call sending a message to the method [ack! phthhht!]

I won't ever talk about "sending a message" in this class. I think it's a

completely misleading metaphor. In computer science, message-passing normally

implies asynchrony: that is, the process that sends a message can continue

executing while the receiving process receives the message and acts on it.

But that's NOT what it means in object-oriented programming: when a Java

method "sends a message" to another method, the former method is frozen until

the latter methods completes execution, just like with procedure calls in most

languages. But you should probably know that this termology exists, much as it

sucks, because you'll probably run into it sooner or later.

�

CS 61B: Lecture 3

Monday, January 27, 2014

Today's reading: Sierra & Bates, pp. 71-74, 76, 85, 240-249, 273-281, 308-309.

DEFINING CLASSES

================

An object is a repository of data. _Fields_ are variables that hold the data

stored in objects. Fields in objects are also known as _instance_variables_.

In Java, fields are addressed much like methods are, but fields never have

parameters, and no parentheses appear after them. For example, suppose that

amanda is a Human object. Then amanda.introduce() is a method call, and

amanda.age is a field. Let's write a _class_definition_ for the Human class.

class Human {

public int age; // The Human's age (an integer).

public String name; // The Human's name.

public void introduce() { // This is a _method_definition_.

System.out.println("I'm " + name + " and I'm " + age + " years old.");

}

}

"age" and "name" are both fields of a Human object. Now that we've defined the

Human class, we can construct as many Human objects as we want. Each Human

object we create can have different values of age and name. We might create

amanda by executing the following code.

Human amanda = new Human(); // Create amanda.

amanda.age = 6; // Set amanda's fields.

amanda.name = "Amanda";

amanda.introduce(); // _Method_call_ has amanda introduce herself.

--------------

| ---- |

--- | age | 6| |

amanda |.+--->| ---- | ------------

--- | name | -+--+---->| "Amanda" |

| ---- | ------------

-------------- a String object

a Human object

The output is: I'm Amanda and I'm 6 years old.

Why is it that, inside the definition of introduce(), we don't have to write

"amanda.name" and "amanda.age"? When we invoke "amanda.introduce()", Java

remembers that we are calling introduce() _on_ the object that "amanda"

references. The methods defined inside the Human class remember that we're

referring to amanda's name and age. If we had written "rishi.introduce()", the

introduce method would print rishi's name and age instead. If we want to mix

two or more objects, we can.

class Human {

// Include all the stuff from the previous definition of Human here.

public void copy(Human original) {

age = original.age;

name = original.name;

}

}

Now, "amanda.copy(rishi)" copies rishi's fields to amanda.

Constructors

------------

Let's write a constructor, a method that constructs a Human. The constructor

won't actually contain code that does the creating; rather, Java provides a

brand new object for us right at the beginning of the constructor, and all you

have to write (if you want) in the constructor is code to initialize the new

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc