人人都撒谎(英文原版) - 副本

Title Page

Foreword

Dedication

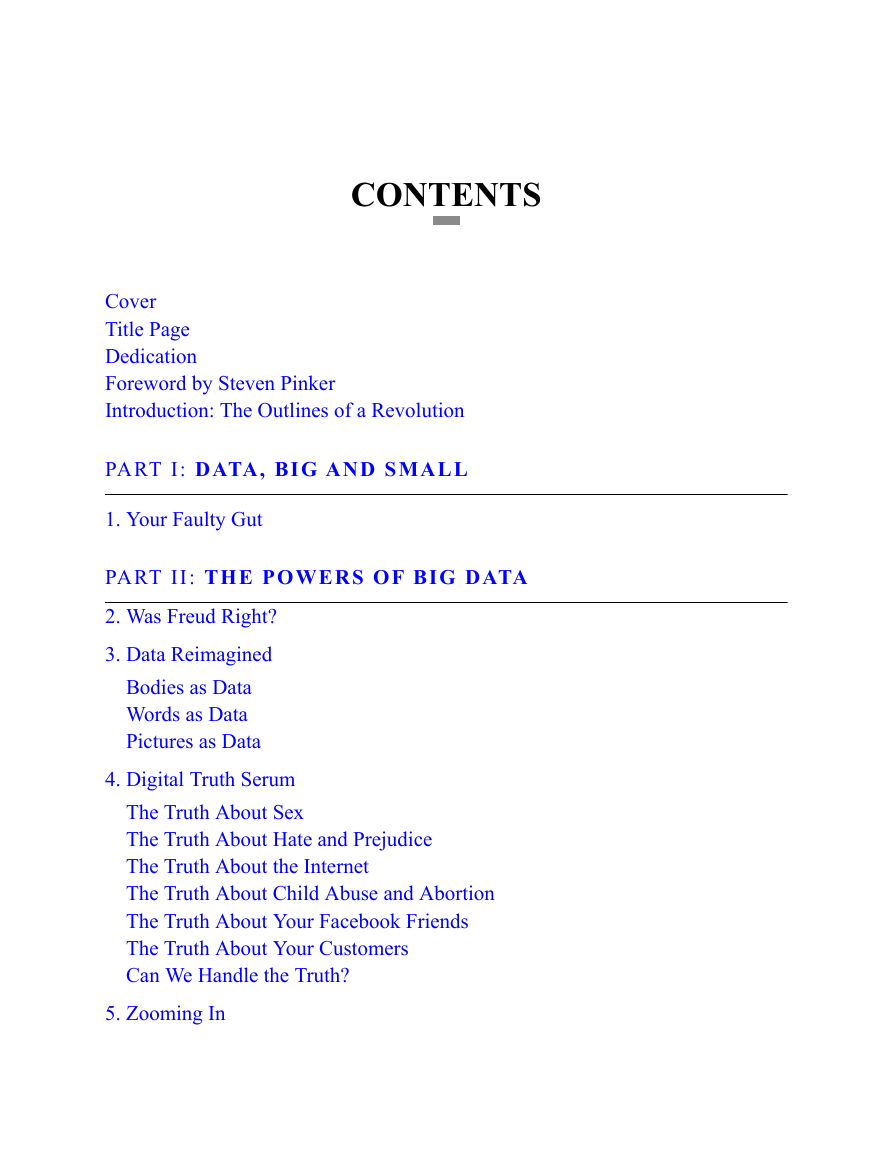

Contents

Introduction: The Outlines of a Revolution

PART I: DATA, BIG AND SMALL

1. Your Faulty Gut

PART II: THE POWERS OF BIG DATA

2. Was Freud Right?

3. Data Reimagined

Bodies as Data

Words as Data

Pictures as Data

4. Digital Truth Serum

The Truth About Sex

The Truth About Hate and Prejudice

The Truth About the Internet

The Truth About Child Abuse and Abortion

The Truth About Your Facebook Friends

The Truth About Your Customers

Can We Handle the Truth?

5. Zooming In

What’s Really Going On in Our Counties, Cities, and Towns?

How We Fill Our Minutes and Hours

Our Doppelgangers

Data Stories

6. All the World’s a Lab

The ABCs of A/B Testing

Nature’s Cruel—but Enlightening—Experiments

PART III: BIG DATA: HANDLE WITH CARE

7. Big Data, Big Schmata? What It Cannot Do

The Curse of Dimensionality

The Overemphasis on What Is Measurable

8. Mo Data, Mo Problems? What We Shouldn’t Do

The Danger of Empowered Corporations

The Danger of Empowered Governments

Conclusion: How Many People Finish Books?

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

人人都撒谎(英文原版)

Title Page

Foreword

Dedication

Contents

Introduction: The Outlines of a Revolution

PART I: DATA, BIG AND SMALL

1. Your Faulty Gut

PART II: THE POWERS OF BIG DATA

2. Was Freud Right?

3. Data Reimagined

Bodies as Data

Words as Data

Pictures as Data

4. Digital Truth Serum

The Truth About Sex

The Truth About Hate and Prejudice

The Truth About the Internet

The Truth About Child Abuse and Abortion

The Truth About Your Facebook Friends

The Truth About Your Customers

Can We Handle the Truth?

5. Zooming In

What’s Really Going On in Our Counties, Cities, and Towns?

How We Fill Our Minutes and Hours

Our Doppelgangers

Data Stories

6. All the World’s a Lab

The ABCs of A/B Testing

Nature’s Cruel—but Enlightening—Experiments

PART III: BIG DATA: HANDLE WITH CARE

7. Big Data, Big Schmata? What It Cannot Do

The Curse of Dimensionality

The Overemphasis on What Is Measurable

8. Mo Data, Mo Problems? What We Shouldn’t Do

The Danger of Empowered Corporations

The Danger of Empowered Governments

Conclusion: How Many People Finish Books?

Acknowledgments

Notes

Index

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc