5

1

0

2

r

p

A

0

1

]

V

C

.

s

c

[

6

v

6

5

5

1

.

9

0

4

1

:

v

i

X

r

a

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2015

VERY DEEP CONVOLUTIONAL NETWORKS

FOR LARGE-SCALE IMAGE RECOGNITION

Karen Simonyan∗ & Andrew Zisserman+

Visual Geometry Group, Department of Engineering Science, University of Oxford

{karen,az}@robots.ox.ac.uk

ABSTRACT

In this work we investigate the effect of the convolutional network depth on its

accuracy in the large-scale image recognition setting. Our main contribution is

a thorough evaluation of networks of increasing depth using an architecture with

very small (3 × 3) convolution filters, which shows that a significant improvement

on the prior-art configurations can be achieved by pushing the depth to 16–19

weight layers. These findings were the basis of our ImageNet Challenge 2014

submission, where our team secured the first and the second places in the localisa-

tion and classification tracks respectively. We also show that our representations

generalise well to other datasets, where they achieve state-of-the-art results. We

have made our two best-performing ConvNet models publicly available to facili-

tate further research on the use of deep visual representations in computer vision.

1

INTRODUCTION

Convolutional networks (ConvNets) have recently enjoyed a great success in large-scale im-

age and video recognition (Krizhevsky et al., 2012; Zeiler & Fergus, 2013; Sermanet et al., 2014;

Simonyan & Zisserman, 2014) which has become possible due to the large public image reposito-

ries, such as ImageNet (Deng et al., 2009), and high-performance computing systems, such as GPUs

or large-scale distributed clusters (Dean et al., 2012). In particular, an important role in the advance

of deep visual recognition architectures has been played by the ImageNet Large-Scale Visual Recog-

nition Challenge (ILSVRC) (Russakovsky et al., 2014), which has served as a testbed for a few

generations of large-scale image classification systems, from high-dimensional shallow feature en-

codings (Perronnin et al., 2010) (the winner of ILSVRC-2011) to deep ConvNets (Krizhevsky et al.,

2012) (the winner of ILSVRC-2012).

With ConvNets becoming more of a commodity in the computer vision field, a number of at-

tempts have been made to improve the original architecture of Krizhevsky et al. (2012) in a

bid to achieve better accuracy. For instance, the best-performing submissions to the ILSVRC-

2013 (Zeiler & Fergus, 2013; Sermanet et al., 2014) utilised smaller receptive window size and

smaller stride of the first convolutional layer. Another line of improvements dealt with training

and testing the networks densely over the whole image and over multiple scales (Sermanet et al.,

2014; Howard, 2014). In this paper, we address another important aspect of ConvNet architecture

design – its depth. To this end, we fix other parameters of the architecture, and steadily increase the

depth of the network by adding more convolutional layers, which is feasible due to the use of very

small (3 × 3) convolution filters in all layers.

As a result, we come up with significantly more accurate ConvNet architectures, which not only

achieve the state-of-the-art accuracy on ILSVRC classification and localisation tasks, but are also

applicable to other image recognition datasets, where they achieve excellent performance even when

used as a part of a relatively simple pipelines (e.g. deep features classified by a linear SVM without

fine-tuning). We have released our two best-performing models1 to facilitate further research.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. In Sect. 2, we describe our ConvNet configurations.

The details of the image classification training and evaluation are then presented in Sect. 3, and the

∗current affiliation: Google DeepMind +current affiliation: University of Oxford and Google DeepMind

1http://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/˜vgg/research/very_deep/

1

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2015

configurations are compared on the ILSVRC classification task in Sect. 4. Sect. 5 concludes the

paper. For completeness, we also describe and assess our ILSVRC-2014 object localisation system

in Appendix A, and discuss the generalisation of very deep features to other datasets in Appendix B.

Finally, Appendix C contains the list of major paper revisions.

2 CONVNET CONFIGURATIONS

To measure the improvement brought by the increased ConvNet depth in a fair setting, all our

ConvNet layer configurations are designed using the same principles, inspired by Ciresan et al.

(2011); Krizhevsky et al. (2012). In this section, we first describe a generic layout of our ConvNet

configurations (Sect. 2.1) and then detail the specific configurations used in the evaluation (Sect. 2.2).

Our design choices are then discussed and compared to the prior art in Sect. 2.3.

2.1 ARCHITECTURE

During training, the input to our ConvNets is a fixed-size 224 × 224 RGB image. The only pre-

processing we do is subtracting the mean RGB value, computed on the training set, from each pixel.

The image is passed through a stack of convolutional (conv.) layers, where we use filters with a very

small receptive field: 3 × 3 (which is the smallest size to capture the notion of left/right, up/down,

center). In one of the configurations we also utilise 1 × 1 convolution filters, which can be seen as

a linear transformation of the input channels (followed by non-linearity). The convolution stride is

fixed to 1 pixel; the spatial padding of conv. layer input is such that the spatial resolution is preserved

after convolution, i.e. the padding is 1 pixel for 3 × 3 conv. layers. Spatial pooling is carried out by

five max-pooling layers, which follow some of the conv. layers (not all the conv. layers are followed

by max-pooling). Max-pooling is performed over a 2 × 2 pixel window, with stride 2.

A stack of convolutional layers (which has a different depth in different architectures) is followed by

three Fully-Connected (FC) layers: the first two have 4096 channels each, the third performs 1000-

way ILSVRC classification and thus contains 1000 channels (one for each class). The final layer is

the soft-max layer. The configuration of the fully connected layers is the same in all networks.

All hidden layers are equipped with the rectification (ReLU (Krizhevsky et al., 2012)) non-linearity.

We note that none of our networks (except for one) contain Local Response Normalisation

(LRN) normalisation (Krizhevsky et al., 2012): as will be shown in Sect. 4, such normalisation

does not improve the performance on the ILSVRC dataset, but leads to increased memory con-

sumption and computation time. Where applicable, the parameters for the LRN layer are those

of (Krizhevsky et al., 2012).

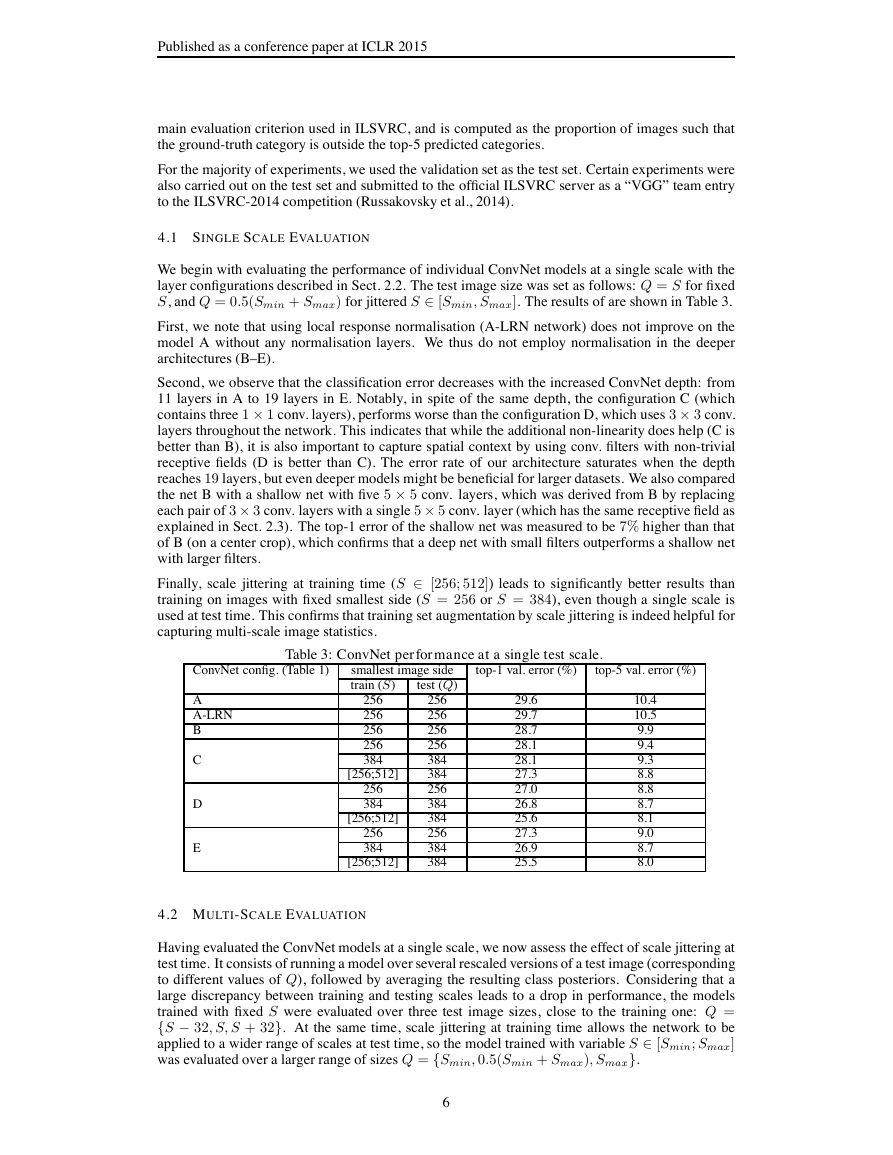

2.2 CONFIGURATIONS

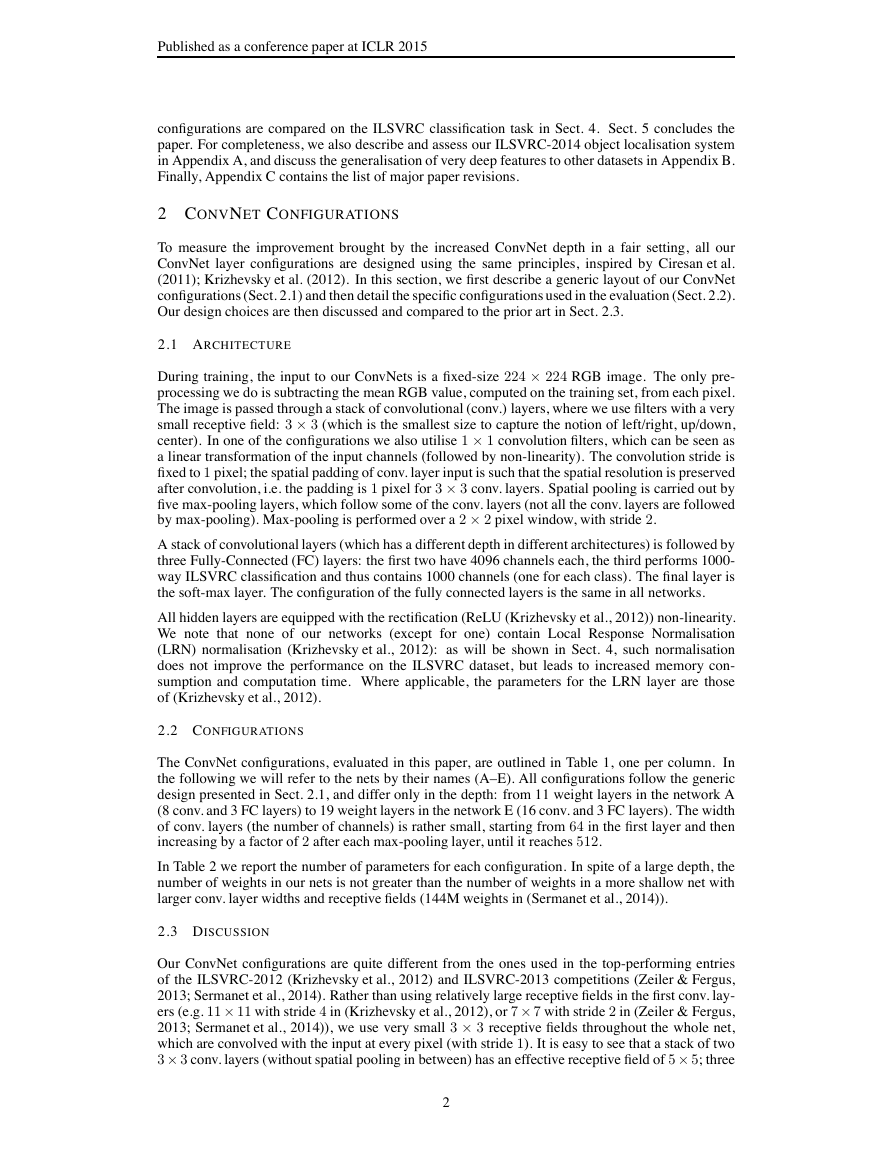

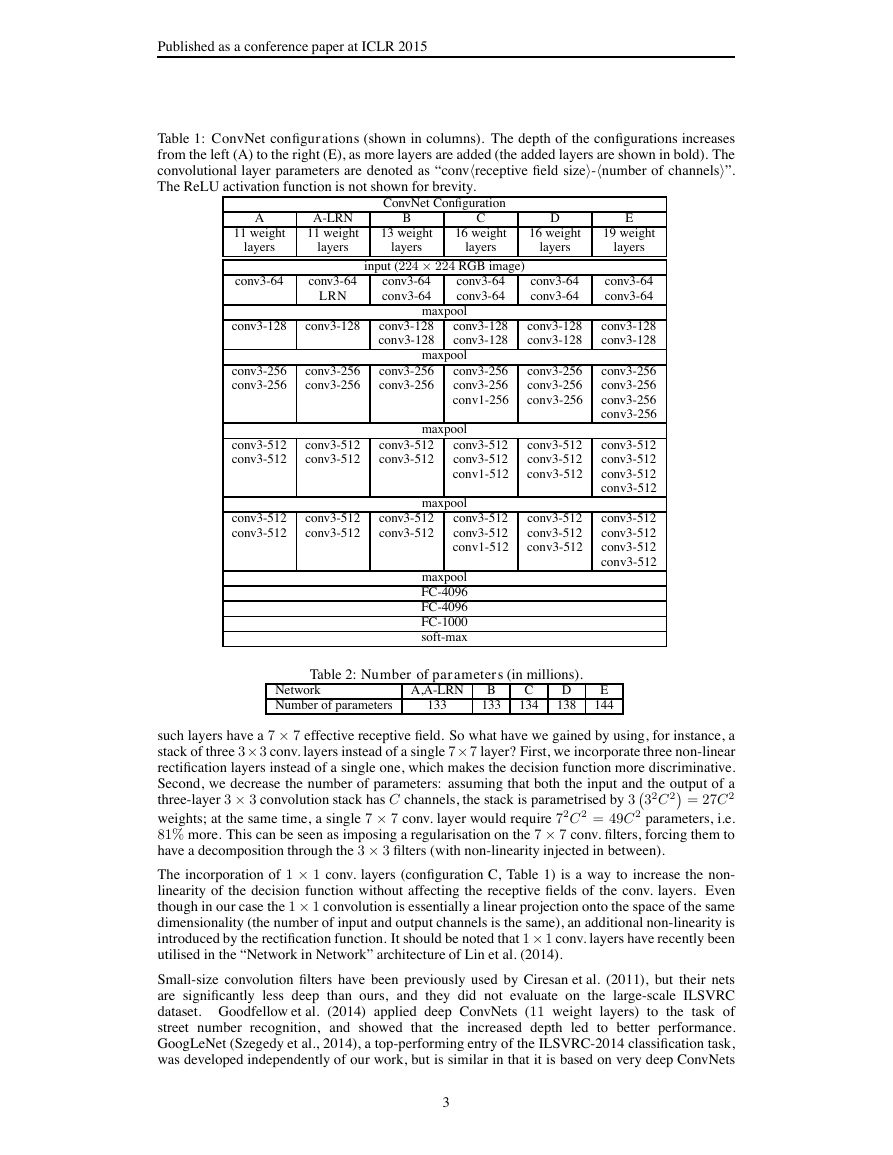

The ConvNet configurations, evaluated in this paper, are outlined in Table 1, one per column. In

the following we will refer to the nets by their names (A–E). All configurations follow the generic

design presented in Sect. 2.1, and differ only in the depth: from 11 weight layers in the network A

(8 conv. and 3 FC layers) to 19 weight layers in the network E (16 conv. and 3 FC layers). The width

of conv. layers (the number of channels) is rather small, starting from 64 in the first layer and then

increasing by a factor of 2 after each max-pooling layer, until it reaches 512.

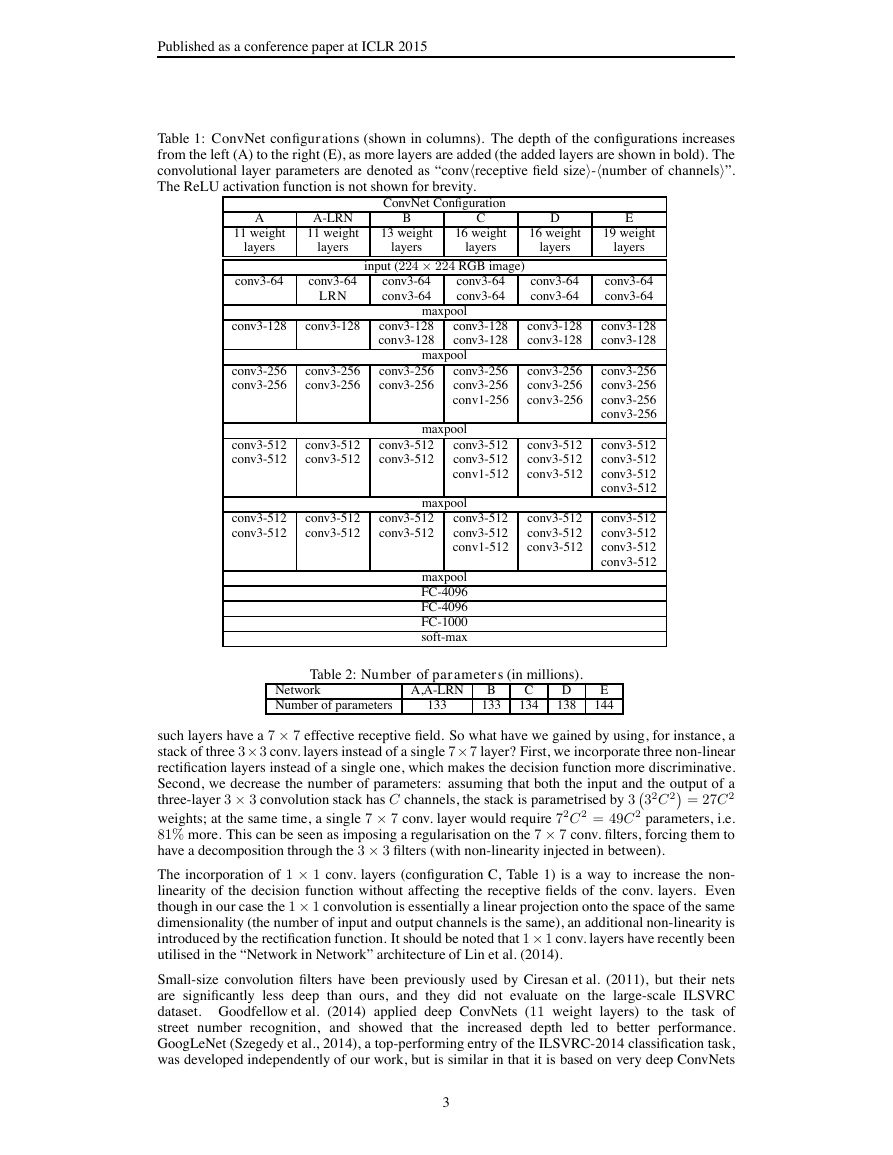

In Table 2 we report the number of parameters for each configuration. In spite of a large depth, the

number of weights in our nets is not greater than the number of weights in a more shallow net with

larger conv. layer widths and receptive fields (144M weights in (Sermanet et al., 2014)).

2.3 DISCUSSION

Our ConvNet configurations are quite different from the ones used in the top-performing entries

of the ILSVRC-2012 (Krizhevsky et al., 2012) and ILSVRC-2013 competitions (Zeiler & Fergus,

2013; Sermanet et al., 2014). Rather than using relatively large receptive fields in the first conv. lay-

ers (e.g. 11 × 11 with stride 4 in (Krizhevsky et al., 2012), or 7 × 7 with stride 2 in (Zeiler & Fergus,

2013; Sermanet et al., 2014)), we use very small 3 × 3 receptive fields throughout the whole net,

which are convolved with the input at every pixel (with stride 1). It is easy to see that a stack of two

3 × 3 conv. layers (without spatial pooling in between) has an effective receptive field of 5 × 5; three

2

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2015

Table 1: ConvNet configurations (shown in columns). The depth of the configurations increases

from the left (A) to the right (E), as more layers are added (the added layers are shown in bold). The

convolutional layer parameters are denoted as “convhreceptive field sizei-hnumber of channelsi”.

The ReLU activation function is not shown for brevity.

ConvNet Configuration

A

11 weight

layers

A-LRN

11 weight

layers

B

C

D

E

13 weight

layers

16 weight

layers

16 weight

layers

19 weight

layers

input (224 × 224 RGB image)

conv3-64

conv3-64

LRN

conv3-64

conv3-64

conv3-64

conv3-64

conv3-64

conv3-64

conv3-64

conv3-64

conv3-128

conv3-128

conv3-128

conv3-128

conv3-128

conv3-128

conv3-128

conv3-128

conv3-128

conv3-128

maxpool

conv3-256

conv3-256

conv3-256

conv3-256

conv3-256

conv3-256

conv3-256

conv3-256

conv1-256

conv3-256

conv3-256

conv3-256

maxpool

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv1-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

maxpool

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv1-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

maxpool

conv3-256

conv3-256

conv3-256

conv3-256

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

conv3-512

maxpool

FC-4096

FC-4096

FC-1000

soft-max

Table 2: Number of parameters (in millions).

Network

Number of parameters

A,A-LRN

133

B

133

C

134

D

138

E

144

such layers have a 7 × 7 effective receptive field. So what have we gained by using, for instance, a

stack of three 3 × 3 conv. layers instead of a single 7 × 7 layer? First, we incorporate three non-linear

rectification layers instead of a single one, which makes the decision function more discriminative.

Second, we decrease the number of parameters: assuming that both the input and the output of a

three-layer 3 × 3 convolution stack has C channels, the stack is parametrised by 3 32C 2 = 27C 2

weights; at the same time, a single 7 × 7 conv. layer would require 72C 2 = 49C 2 parameters, i.e.

81% more. This can be seen as imposing a regularisation on the 7 × 7 conv. filters, forcing them to

have a decomposition through the 3 × 3 filters (with non-linearity injected in between).

The incorporation of 1 × 1 conv. layers (configuration C, Table 1) is a way to increase the non-

linearity of the decision function without affecting the receptive fields of the conv. layers. Even

though in our case the 1 × 1 convolution is essentially a linear projection onto the space of the same

dimensionality (the number of input and output channels is the same), an additional non-linearity is

introduced by the rectification function. It should be noted that 1 × 1 conv. layers have recently been

utilised in the “Network in Network” architecture of Lin et al. (2014).

Small-size convolution filters have been previously used by Ciresan et al. (2011), but their nets

are significantly less deep than ours, and they did not evaluate on the large-scale ILSVRC

dataset. Goodfellow et al. (2014) applied deep ConvNets (11 weight layers) to the task of

street number recognition, and showed that

the increased depth led to better performance.

GoogLeNet (Szegedy et al., 2014), a top-performing entry of the ILSVRC-2014 classification task,

was developed independently of our work, but is similar in that it is based on very deep ConvNets

3

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2015

(22 weight layers) and small convolution filters (apart from 3 × 3, they also use 1 × 1 and 5 × 5

convolutions). Their network topology is, however, more complex than ours, and the spatial reso-

lution of the feature maps is reduced more aggressively in the first layers to decrease the amount

of computation. As will be shown in Sect. 4.5, our model is outperforming that of Szegedy et al.

(2014) in terms of the single-network classification accuracy.

3 CLASSIFICATION FRAMEWORK

In the previous section we presented the details of our network configurations. In this section, we

describe the details of classification ConvNet training and evaluation.

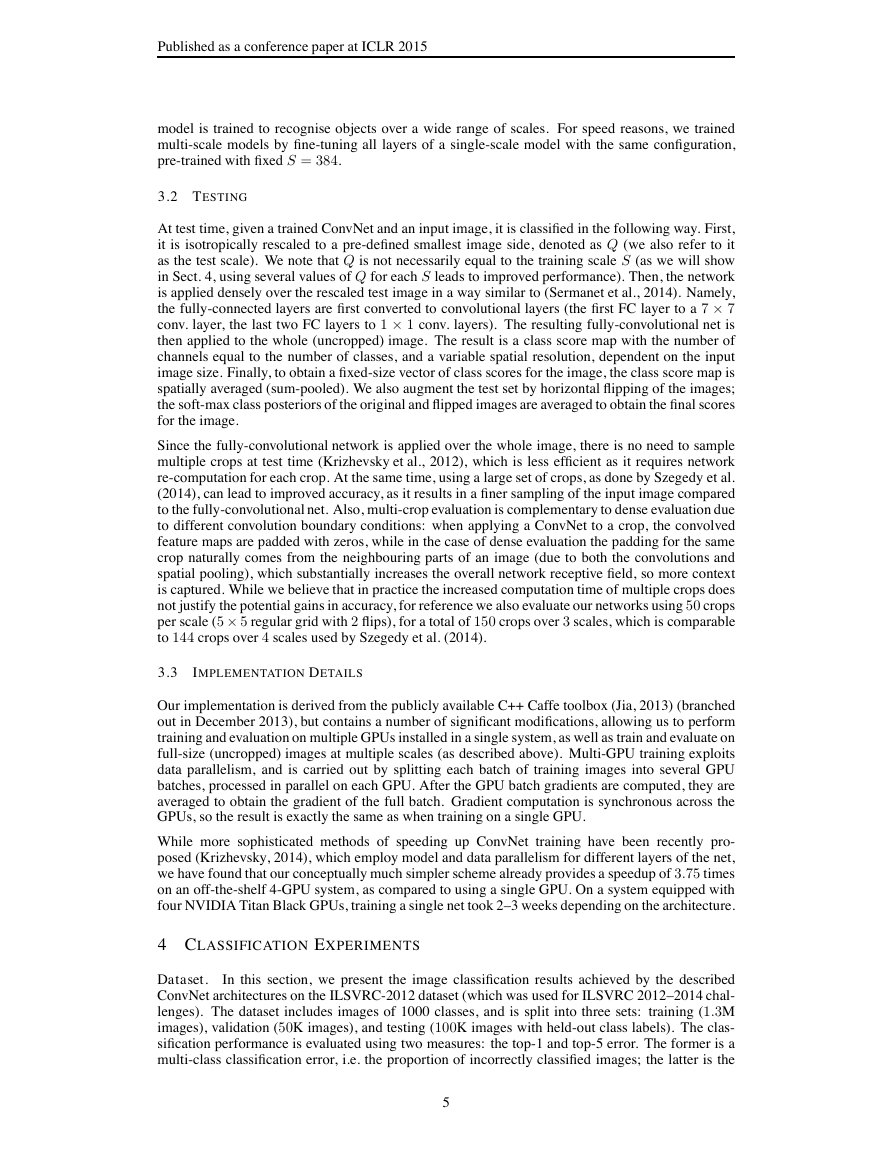

3.1 TRAINING

The ConvNet training procedure generally follows Krizhevsky et al. (2012) (except for sampling

the input crops from multi-scale training images, as explained later). Namely, the training is carried

out by optimising the multinomial logistic regression objective using mini-batch gradient descent

(based on back-propagation (LeCun et al., 1989)) with momentum. The batch size was set to 256,

momentum to 0.9. The training was regularised by weight decay (the L2 penalty multiplier set to

5 · 10−4) and dropout regularisation for the first two fully-connected layers (dropout ratio set to 0.5).

The learning rate was initially set to 10−2, and then decreased by a factor of 10 when the validation

set accuracy stopped improving. In total, the learning rate was decreased 3 times, and the learning

was stopped after 370K iterations (74 epochs). We conjecture that in spite of the larger number of

parameters and the greater depth of our nets compared to (Krizhevsky et al., 2012), the nets required

less epochs to converge due to (a) implicit regularisation imposed by greater depth and smaller conv.

filter sizes; (b) pre-initialisation of certain layers.

The initialisation of the network weights is important, since bad initialisation can stall learning due

to the instability of gradient in deep nets. To circumvent this problem, we began with training

the configuration A (Table 1), shallow enough to be trained with random initialisation. Then, when

training deeper architectures, we initialised the first four convolutional layers and the last three fully-

connected layers with the layers of net A (the intermediate layers were initialised randomly). We did

not decrease the learning rate for the pre-initialised layers, allowing them to change during learning.

For random initialisation (where applicable), we sampled the weights from a normal distribution

with the zero mean and 10−2 variance. The biases were initialised with zero. It is worth noting that

after the paper submission we found that it is possible to initialise the weights without pre-training

by using the random initialisation procedure of Glorot & Bengio (2010).

To obtain the fixed-size 224×224 ConvNet input images, they were randomly cropped from rescaled

training images (one crop per image per SGD iteration). To further augment the training set, the

crops underwent random horizontal flipping and random RGB colour shift (Krizhevsky et al., 2012).

Training image rescaling is explained below.

Training image size. Let S be the smallest side of an isotropically-rescaled training image, from

which the ConvNet input is cropped (we also refer to S as the training scale). While the crop size

is fixed to 224 × 224, in principle S can take on any value not less than 224: for S = 224 the crop

will capture whole-image statistics, completely spanning the smallest side of a training image; for

S ≫ 224 the crop will correspond to a small part of the image, containing a small object or an object

part.

We consider two approaches for setting the training scale S. The first is to fix S, which corresponds

to single-scale training (note that image content within the sampled crops can still represent multi-

scale image statistics). In our experiments, we evaluated models trained at two fixed scales: S =

256 (which has been widely used in the prior art (Krizhevsky et al., 2012; Zeiler & Fergus, 2013;

Sermanet et al., 2014)) and S = 384. Given a ConvNet configuration, we first trained the network

using S = 256. To speed-up training of the S = 384 network, it was initialised with the weights

pre-trained with S = 256, and we used a smaller initial learning rate of 10−3.

The second approach to setting S is multi-scale training, where each training image is individually

rescaled by randomly sampling S from a certain range [Smin, Smax] (we used Smin = 256 and

Smax = 512). Since objects in images can be of different size, it is beneficial to take this into account

during training. This can also be seen as training set augmentation by scale jittering, where a single

4

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2015

model is trained to recognise objects over a wide range of scales. For speed reasons, we trained

multi-scale models by fine-tuning all layers of a single-scale model with the same configuration,

pre-trained with fixed S = 384.

3.2 TESTING

At test time, given a trained ConvNet and an input image, it is classified in the following way. First,

it is isotropically rescaled to a pre-defined smallest image side, denoted as Q (we also refer to it

as the test scale). We note that Q is not necessarily equal to the training scale S (as we will show

in Sect. 4, using several values of Q for each S leads to improved performance). Then, the network

is applied densely over the rescaled test image in a way similar to (Sermanet et al., 2014). Namely,

the fully-connected layers are first converted to convolutional layers (the first FC layer to a 7 × 7

conv. layer, the last two FC layers to 1 × 1 conv. layers). The resulting fully-convolutional net is

then applied to the whole (uncropped) image. The result is a class score map with the number of

channels equal to the number of classes, and a variable spatial resolution, dependent on the input

image size. Finally, to obtain a fixed-size vector of class scores for the image, the class score map is

spatially averaged (sum-pooled). We also augment the test set by horizontal flipping of the images;

the soft-max class posteriors of the original and flipped images are averaged to obtain the final scores

for the image.

Since the fully-convolutional network is applied over the whole image, there is no need to sample

multiple crops at test time (Krizhevsky et al., 2012), which is less efficient as it requires network

re-computation for each crop. At the same time, using a large set of crops, as done by Szegedy et al.

(2014), can lead to improved accuracy, as it results in a finer sampling of the input image compared

to the fully-convolutional net. Also, multi-crop evaluation is complementary to dense evaluation due

to different convolution boundary conditions: when applying a ConvNet to a crop, the convolved

feature maps are padded with zeros, while in the case of dense evaluation the padding for the same

crop naturally comes from the neighbouring parts of an image (due to both the convolutions and

spatial pooling), which substantially increases the overall network receptive field, so more context

is captured. While we believe that in practice the increased computation time of multiple crops does

not justify the potential gains in accuracy, for reference we also evaluate our networks using 50 crops

per scale (5 × 5 regular grid with 2 flips), for a total of 150 crops over 3 scales, which is comparable

to 144 crops over 4 scales used by Szegedy et al. (2014).

3.3

IMPLEMENTATION DETAILS

Our implementation is derived from the publicly available C++ Caffe toolbox (Jia, 2013) (branched

out in December 2013), but contains a number of significant modifications, allowing us to perform

training and evaluation on multiple GPUs installed in a single system, as well as train and evaluate on

full-size (uncropped) images at multiple scales (as described above). Multi-GPU training exploits

data parallelism, and is carried out by splitting each batch of training images into several GPU

batches, processed in parallel on each GPU. After the GPU batch gradients are computed, they are

averaged to obtain the gradient of the full batch. Gradient computation is synchronous across the

GPUs, so the result is exactly the same as when training on a single GPU.

While more sophisticated methods of speeding up ConvNet training have been recently pro-

posed (Krizhevsky, 2014), which employ model and data parallelism for different layers of the net,

we have found that our conceptually much simpler scheme already provides a speedup of 3.75 times

on an off-the-shelf 4-GPU system, as compared to using a single GPU. On a system equipped with

four NVIDIA Titan Black GPUs, training a single net took 2–3 weeks depending on the architecture.

4 CLASSIFICATION EXPERIMENTS

Dataset.

In this section, we present the image classification results achieved by the described

ConvNet architectures on the ILSVRC-2012 dataset (which was used for ILSVRC 2012–2014 chal-

lenges). The dataset includes images of 1000 classes, and is split into three sets: training (1.3M

images), validation (50K images), and testing (100K images with held-out class labels). The clas-

sification performance is evaluated using two measures: the top-1 and top-5 error. The former is a

multi-class classification error, i.e. the proportion of incorrectly classified images; the latter is the

5

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2015

main evaluation criterion used in ILSVRC, and is computed as the proportion of images such that

the ground-truth category is outside the top-5 predicted categories.

For the majority of experiments, we used the validation set as the test set. Certain experiments were

also carried out on the test set and submitted to the official ILSVRC server as a “VGG” team entry

to the ILSVRC-2014 competition (Russakovsky et al., 2014).

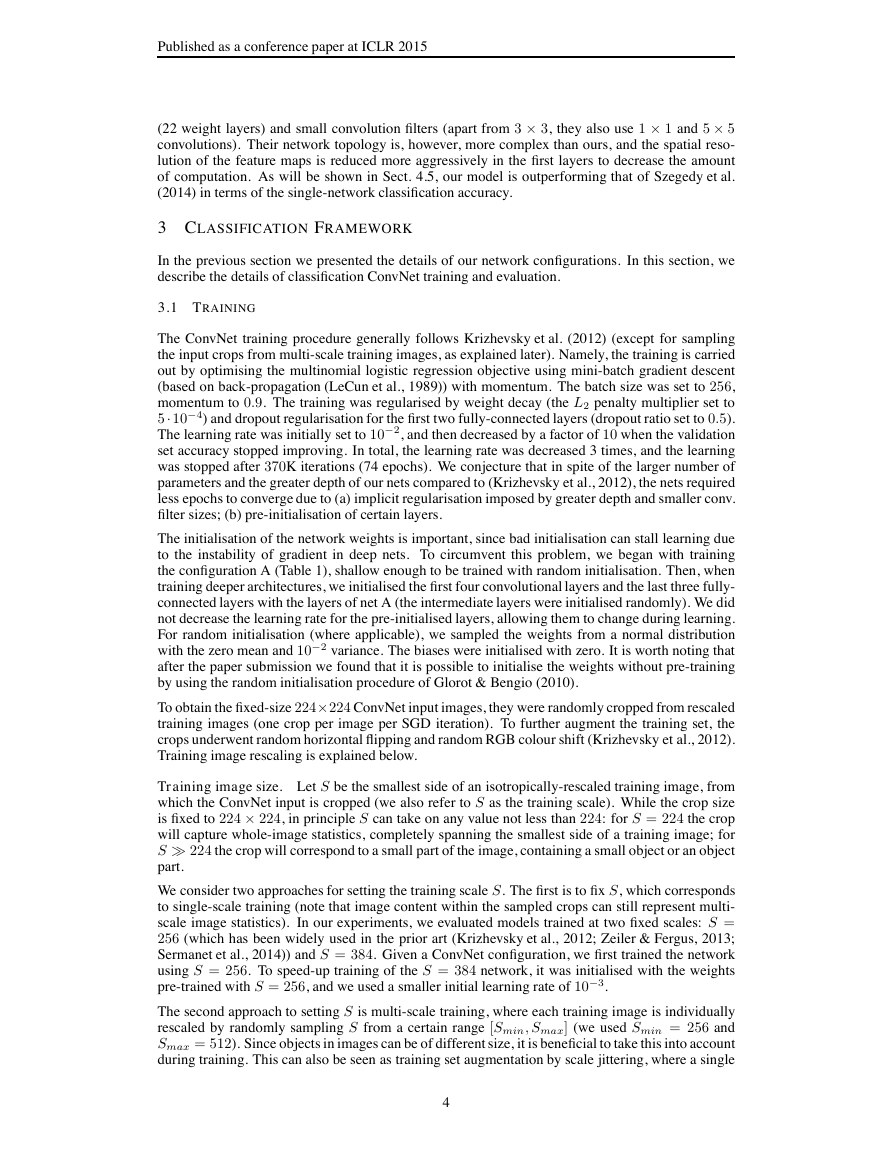

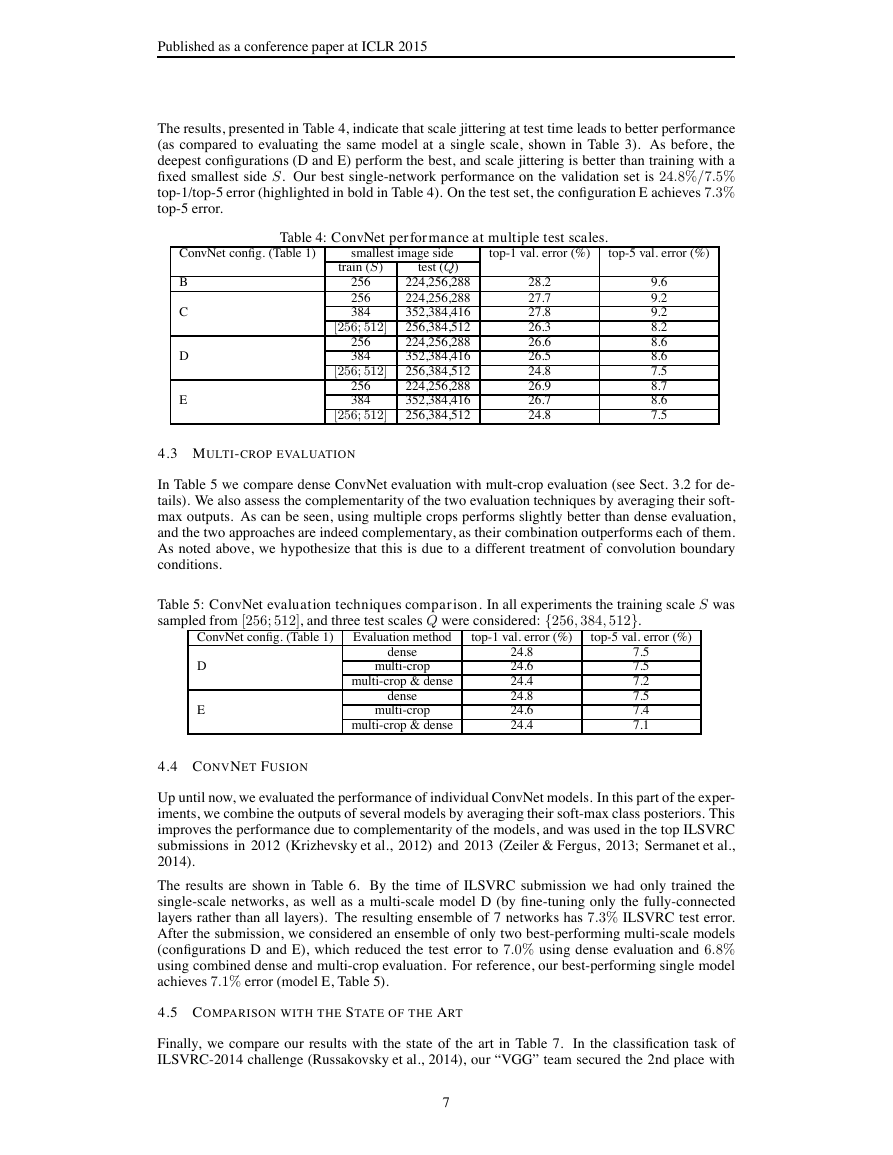

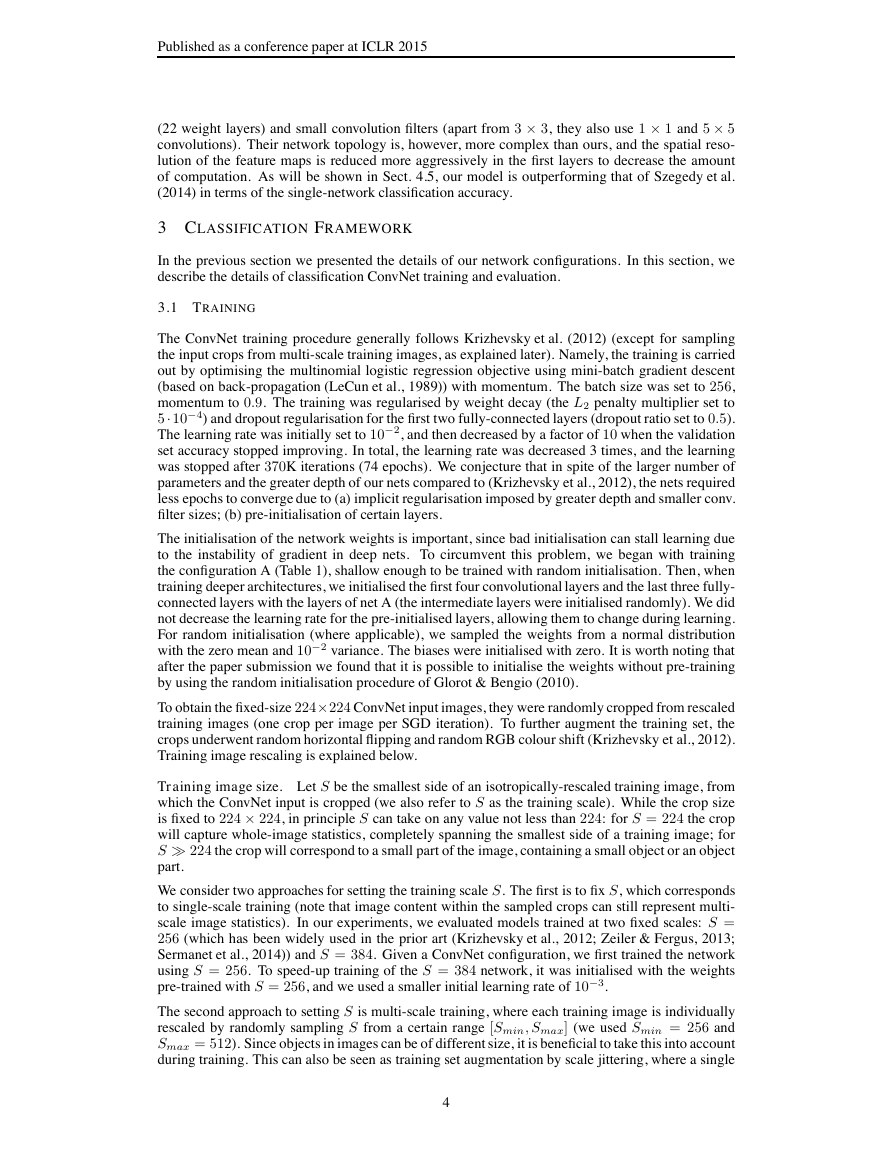

4.1 SINGLE SCALE EVALUATION

We begin with evaluating the performance of individual ConvNet models at a single scale with the

layer configurations described in Sect. 2.2. The test image size was set as follows: Q = S for fixed

S, and Q = 0.5(Smin + Smax) for jittered S ∈ [Smin, Smax]. The results of are shown in Table 3.

First, we note that using local response normalisation (A-LRN network) does not improve on the

model A without any normalisation layers. We thus do not employ normalisation in the deeper

architectures (B–E).

Second, we observe that the classification error decreases with the increased ConvNet depth: from

11 layers in A to 19 layers in E. Notably, in spite of the same depth, the configuration C (which

contains three 1 × 1 conv. layers), performs worse than the configuration D, which uses 3 × 3 conv.

layers throughout the network. This indicates that while the additional non-linearity does help (C is

better than B), it is also important to capture spatial context by using conv. filters with non-trivial

receptive fields (D is better than C). The error rate of our architecture saturates when the depth

reaches 19 layers, but even deeper models might be beneficial for larger datasets. We also compared

the net B with a shallow net with five 5 × 5 conv. layers, which was derived from B by replacing

each pair of 3 × 3 conv. layers with a single 5 × 5 conv. layer (which has the same receptive field as

explained in Sect. 2.3). The top-1 error of the shallow net was measured to be 7% higher than that

of B (on a center crop), which confirms that a deep net with small filters outperforms a shallow net

with larger filters.

Finally, scale jittering at training time (S ∈ [256; 512]) leads to significantly better results than

training on images with fixed smallest side (S = 256 or S = 384), even though a single scale is

used at test time. This confirms that training set augmentation by scale jittering is indeed helpful for

capturing multi-scale image statistics.

Table 3: ConvNet performance at a single test scale.

ConvNet config. (Table 1)

smallest image side

train (S)

test (Q)

top-1 val. error (%)

top-5 val. error (%)

A

A-LRN

B

C

D

E

256

256

256

256

384

[256;512]

256

384

[256;512]

256

384

[256;512]

256

256

256

256

384

384

256

384

384

256

384

384

29.6

29.7

28.7

28.1

28.1

27.3

27.0

26.8

25.6

27.3

26.9

25.5

10.4

10.5

9.9

9.4

9.3

8.8

8.8

8.7

8.1

9.0

8.7

8.0

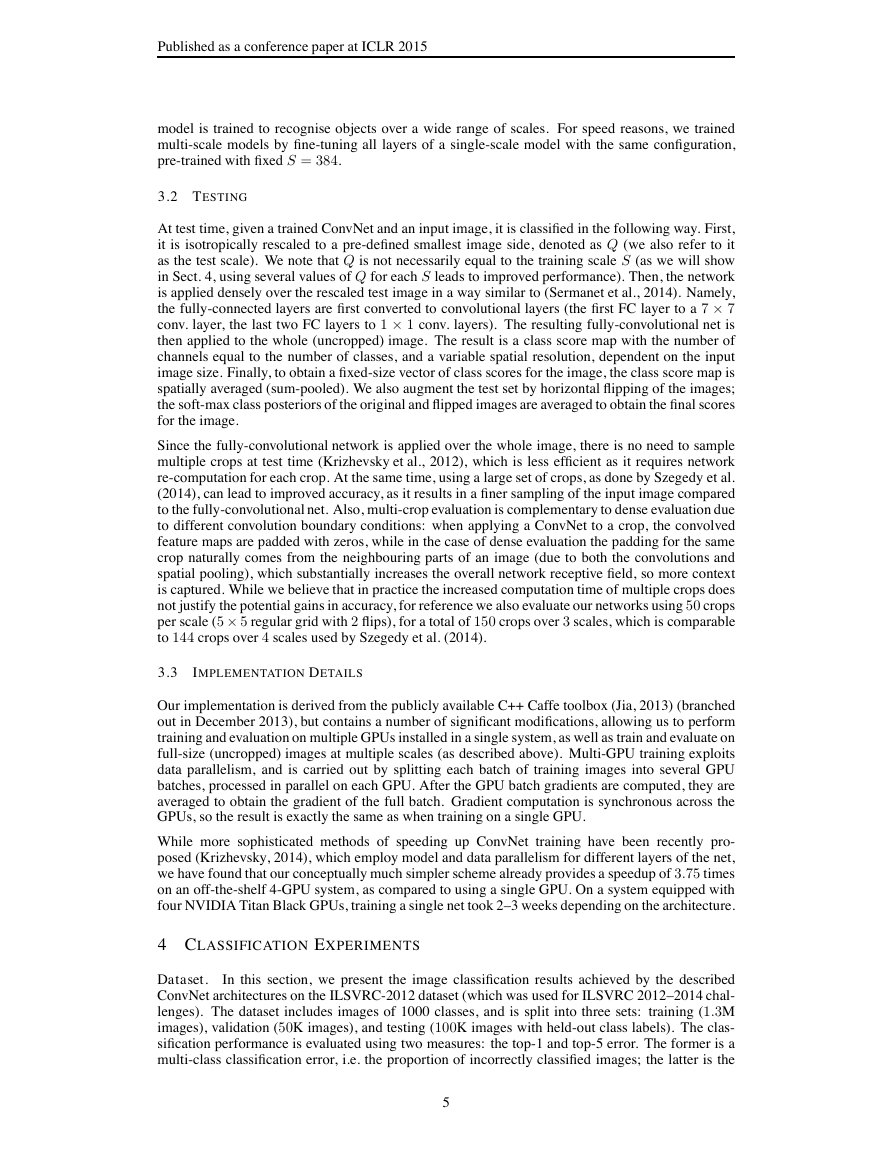

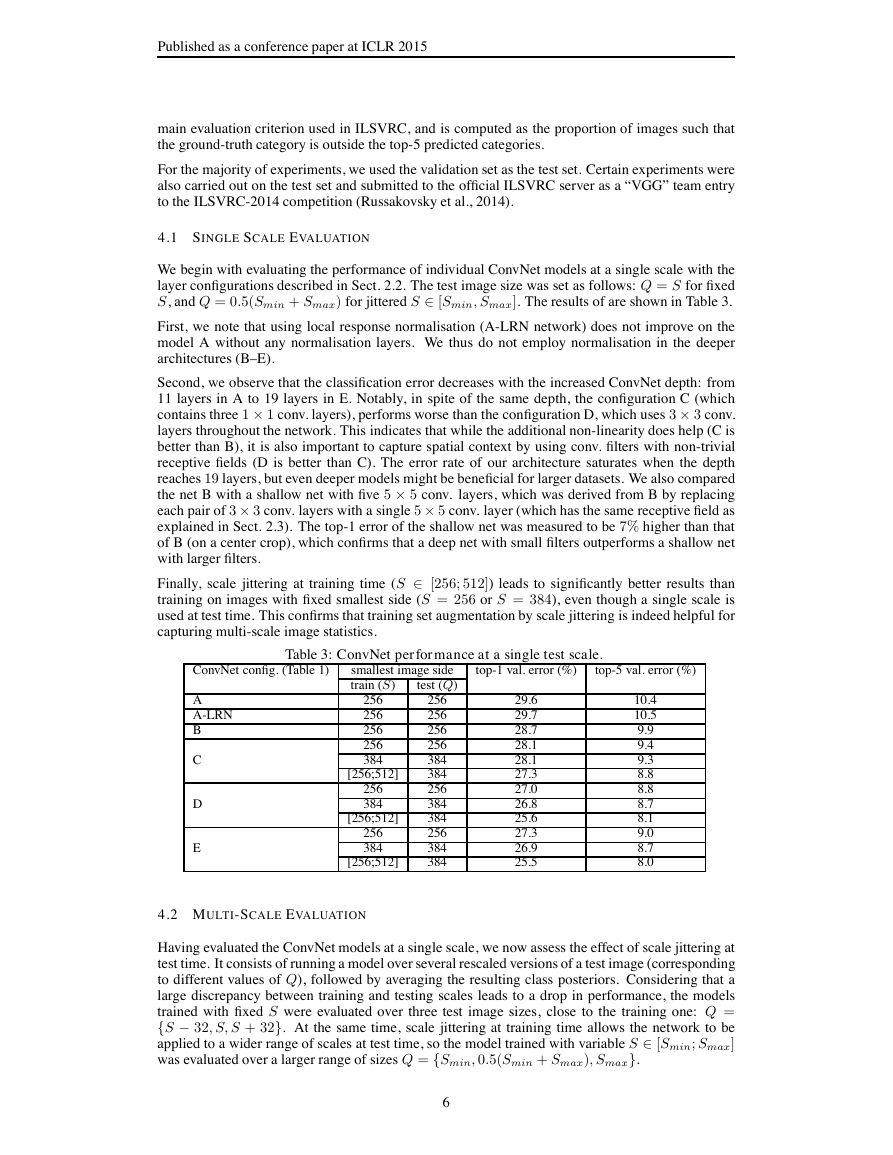

4.2 MULTI-SCALE EVALUATION

Having evaluated the ConvNet models at a single scale, we now assess the effect of scale jittering at

test time. It consists of running a model over several rescaled versions of a test image (corresponding

to different values of Q), followed by averaging the resulting class posteriors. Considering that a

large discrepancy between training and testing scales leads to a drop in performance, the models

trained with fixed S were evaluated over three test image sizes, close to the training one: Q =

{S − 32, S, S + 32}. At the same time, scale jittering at training time allows the network to be

applied to a wider range of scales at test time, so the model trained with variable S ∈ [Smin; Smax]

was evaluated over a larger range of sizes Q = {Smin, 0.5(Smin + Smax), Smax}.

6

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2015

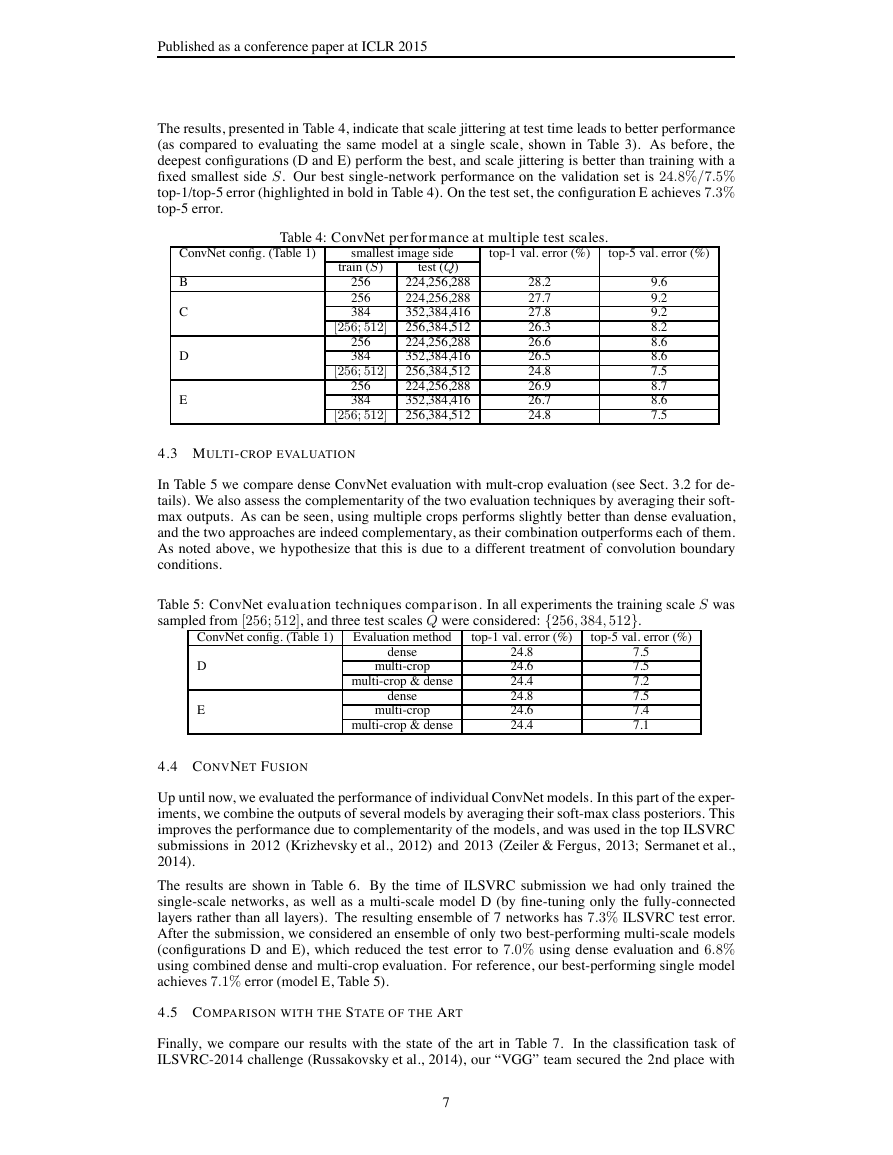

The results, presented in Table 4, indicate that scale jittering at test time leads to better performance

(as compared to evaluating the same model at a single scale, shown in Table 3). As before, the

deepest configurations (D and E) perform the best, and scale jittering is better than training with a

fixed smallest side S. Our best single-network performance on the validation set is 24.8%/7.5%

top-1/top-5 error (highlighted in bold in Table 4). On the test set, the configuration E achieves 7.3%

top-5 error.

Table 4: ConvNet performance at multiple test scales.

ConvNet config. (Table 1)

smallest image side

test (Q)

train (S)

top-1 val. error (%)

top-5 val. error (%)

B

C

D

E

256

256

384

[256; 512]

256

384

[256; 512]

256

384

[256; 512]

224,256,288

224,256,288

352,384,416

256,384,512

224,256,288

352,384,416

256,384,512

224,256,288

352,384,416

256,384,512

28.2

27.7

27.8

26.3

26.6

26.5

24.8

26.9

26.7

24.8

9.6

9.2

9.2

8.2

8.6

8.6

7.5

8.7

8.6

7.5

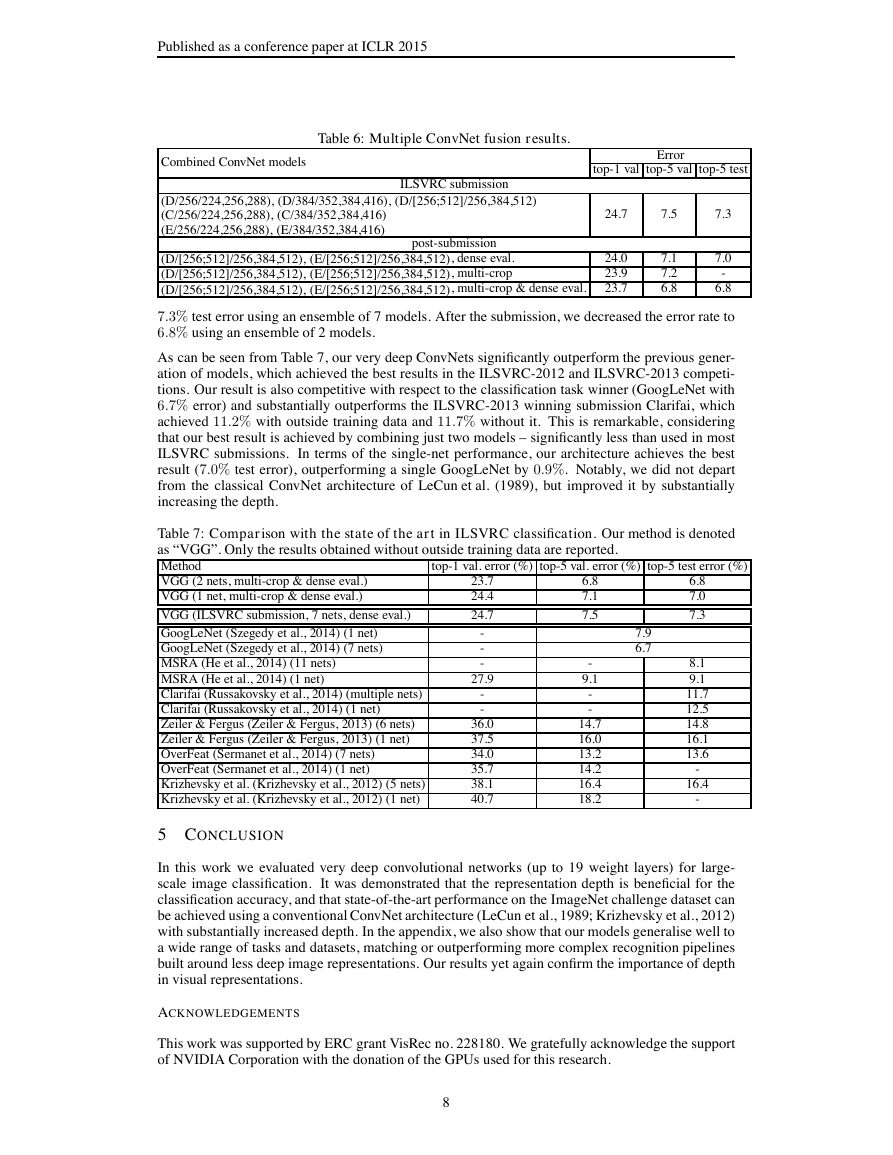

4.3 MULTI-CROP EVALUATION

In Table 5 we compare dense ConvNet evaluation with mult-crop evaluation (see Sect. 3.2 for de-

tails). We also assess the complementarity of the two evaluation techniques by averaging their soft-

max outputs. As can be seen, using multiple crops performs slightly better than dense evaluation,

and the two approaches are indeed complementary, as their combination outperforms each of them.

As noted above, we hypothesize that this is due to a different treatment of convolution boundary

conditions.

Table 5: ConvNet evaluation techniques comparison. In all experiments the training scale S was

sampled from [256; 512], and three test scales Q were considered: {256, 384, 512}.

ConvNet config. (Table 1)

Evaluation method

top-1 val. error (%)

top-5 val. error (%)

D

E

4.4 CONVNET FUSION

dense

multi-crop

multi-crop & dense

dense

multi-crop

multi-crop & dense

24.8

24.6

24.4

24.8

24.6

24.4

7.5

7.5

7.2

7.5

7.4

7.1

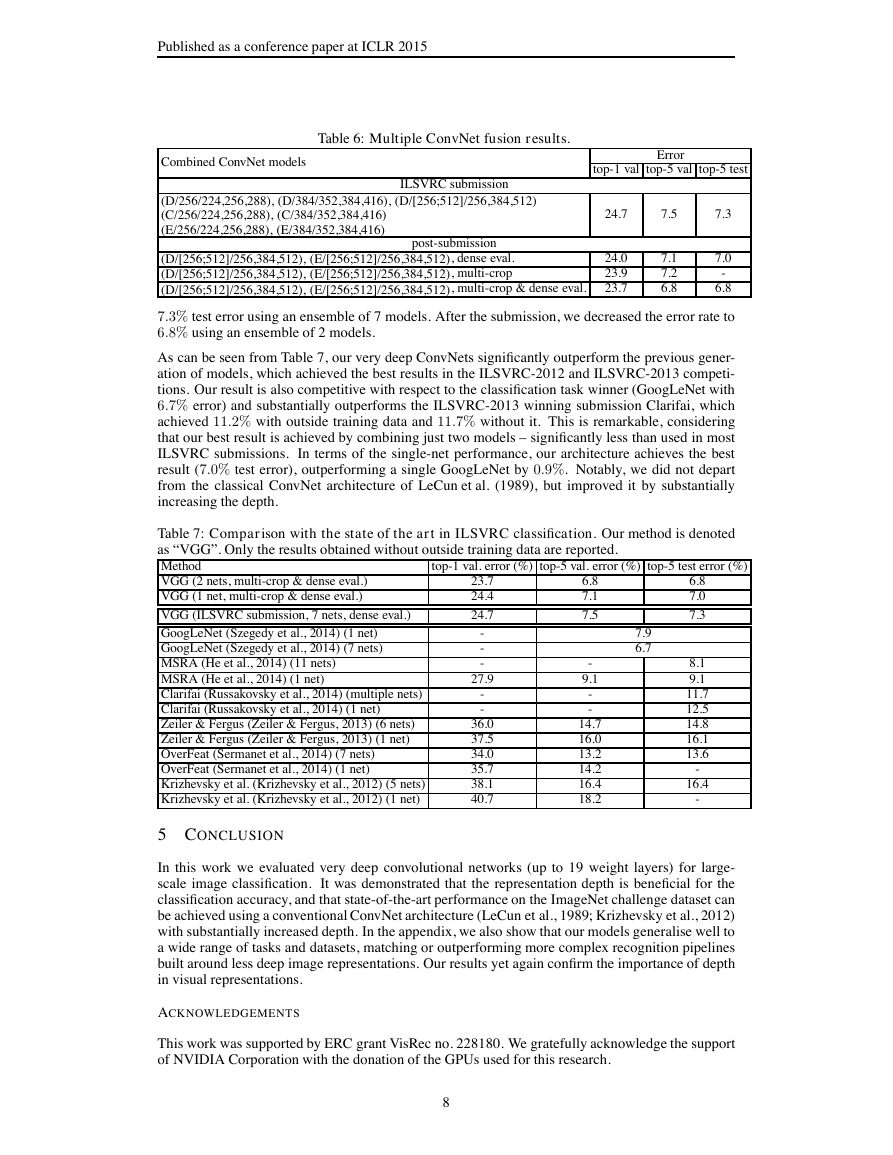

Up until now, we evaluated the performance of individual ConvNet models. In this part of the exper-

iments, we combine the outputs of several models by averaging their soft-max class posteriors. This

improves the performance due to complementarity of the models, and was used in the top ILSVRC

submissions in 2012 (Krizhevsky et al., 2012) and 2013 (Zeiler & Fergus, 2013; Sermanet et al.,

2014).

The results are shown in Table 6. By the time of ILSVRC submission we had only trained the

single-scale networks, as well as a multi-scale model D (by fine-tuning only the fully-connected

layers rather than all layers). The resulting ensemble of 7 networks has 7.3% ILSVRC test error.

After the submission, we considered an ensemble of only two best-performing multi-scale models

(configurations D and E), which reduced the test error to 7.0% using dense evaluation and 6.8%

using combined dense and multi-crop evaluation. For reference, our best-performing single model

achieves 7.1% error (model E, Table 5).

4.5 COMPARISON WITH THE STATE OF THE ART

Finally, we compare our results with the state of the art in Table 7. In the classification task of

ILSVRC-2014 challenge (Russakovsky et al., 2014), our “VGG” team secured the 2nd place with

7

�

Published as a conference paper at ICLR 2015

Combined ConvNet models

Table 6: Multiple ConvNet fusion results.

Error

top-1 val top-5 val top-5 test

ILSVRC submission

(D/256/224,256,288), (D/384/352,384,416), (D/[256;512]/256,384,512)

(C/256/224,256,288), (C/384/352,384,416)

(E/256/224,256,288), (E/384/352,384,416)

post-submission

(D/[256;512]/256,384,512), (E/[256;512]/256,384,512), dense eval.

(D/[256;512]/256,384,512), (E/[256;512]/256,384,512), multi-crop

(D/[256;512]/256,384,512), (E/[256;512]/256,384,512), multi-crop & dense eval.

24.7

24.0

23.9

23.7

7.5

7.1

7.2

6.8

7.3

7.0

-

6.8

7.3% test error using an ensemble of 7 models. After the submission, we decreased the error rate to

6.8% using an ensemble of 2 models.

As can be seen from Table 7, our very deep ConvNets significantly outperform the previous gener-

ation of models, which achieved the best results in the ILSVRC-2012 and ILSVRC-2013 competi-

tions. Our result is also competitive with respect to the classification task winner (GoogLeNet with

6.7% error) and substantially outperforms the ILSVRC-2013 winning submission Clarifai, which

achieved 11.2% with outside training data and 11.7% without it. This is remarkable, considering

that our best result is achieved by combining just two models – significantly less than used in most

ILSVRC submissions. In terms of the single-net performance, our architecture achieves the best

result (7.0% test error), outperforming a single GoogLeNet by 0.9%. Notably, we did not depart

from the classical ConvNet architecture of LeCun et al. (1989), but improved it by substantially

increasing the depth.

top-1 val. error (%) top-5 val. error (%) top-5 test error (%)

23.7

24.4

24.7

Table 7: Comparison with the state of the art in ILSVRC classification. Our method is denoted

as “VGG”. Only the results obtained without outside training data are reported.

Method

VGG (2 nets, multi-crop & dense eval.)

VGG (1 net, multi-crop & dense eval.)

VGG (ILSVRC submission, 7 nets, dense eval.)

GoogLeNet (Szegedy et al., 2014) (1 net)

GoogLeNet (Szegedy et al., 2014) (7 nets)

MSRA (He et al., 2014) (11 nets)

MSRA (He et al., 2014) (1 net)

Clarifai (Russakovsky et al., 2014) (multiple nets)

Clarifai (Russakovsky et al., 2014) (1 net)

Zeiler & Fergus (Zeiler & Fergus, 2013) (6 nets)

Zeiler & Fergus (Zeiler & Fergus, 2013) (1 net)

OverFeat (Sermanet et al., 2014) (7 nets)

OverFeat (Sermanet et al., 2014) (1 net)

Krizhevsky et al. (Krizhevsky et al., 2012) (5 nets)

Krizhevsky et al. (Krizhevsky et al., 2012) (1 net)

8.1

9.1

11.7

12.5

14.8

16.1

13.6

36.0

37.5

34.0

35.7

38.1

40.7

14.7

16.0

13.2

14.2

16.4

18.2

6.8

7.1

7.5

-

9.1

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

27.9

7.9

6.7

6.8

7.0

7.3

16.4

-

-

5 CONCLUSION

In this work we evaluated very deep convolutional networks (up to 19 weight layers) for large-

scale image classification. It was demonstrated that the representation depth is beneficial for the

classification accuracy, and that state-of-the-art performance on the ImageNet challenge dataset can

be achieved using a conventional ConvNet architecture (LeCun et al., 1989; Krizhevsky et al., 2012)

with substantially increased depth. In the appendix, we also show that our models generalise well to

a wide range of tasks and datasets, matching or outperforming more complex recognition pipelines

built around less deep image representations. Our results yet again confirm the importance of depth

in visual representations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by ERC grant VisRec no. 228180. We gratefully acknowledge the support

of NVIDIA Corporation with the donation of the GPUs used for this research.

8

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc