Justin Zobel

Writing for

Computer

Science

Third Edition

�

Writing for Computer Science

�

Justin Zobel

Writing for Computer

Science

Third Edition

123

�

Justin Zobel

Department of Computing

and Information Systems

The University of Melbourne

Parkville

Australia

ISBN 978-1-4471-6638-2

DOI 10.1007/978-1-4471-6639-9

ISBN 978-1-4471-6639-9

(eBook)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014956905

Springer London Heidelberg New York Dordrecht

© Springer-Verlag London 1997, 2004, 2014

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part

of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations,

recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission

or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or

dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this

publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt

from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this

book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the

authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained

herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made.

Printed on acid-free paper

Springer-Verlag London Ltd. is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com)

�

Preface

Writing for Computer Science is an introduction to doing and describing research.

For the most part the book is a discussion of good writing style and effective

research strategies, with a focus on the skills required of graduate research students.

Some of the material is accepted wisdom, some is controversial, and some are my

opinions. The book is intended to be comprehensive; it is broad rather than deep,

but, while some readers may be interested in exploring topics further, for most

readers this book should be sufficient.

The first edition of this book was almost entirely about writing. The second

edition, in response to reader feedback, and in response to issues that arose in my

own experiences as an advisor, researcher, and referee, was additionally about

research methods. Indeed, the two topics—writing about and doing research—are

not clearly separated: it is a small step from asking how do I write? to asking what

is it that I write about?

In this new edition, the third, I’ve further expanded the material on research

methods, as well as refining and extending the guidance on writing. There is a new

chapter, on professional communication beyond academia; the chapters on getting

started, reading, reviewing, hypotheses, experiments, and statistics have been

expanded and reorganized; and there is additional or new material on many topics,

including theses, posters, presentations, literature reviews, measurement and vari-

ability, evidence, data, and common failings in papers. Every chapter has had some

revision, and reader feedback has again been importance in shaping changes. The

references have been removed; with so many excellent, up-to-date reading lists

available at the click of a search button, a static list seemed anachronistic. The

example slides have been dropped too; there are limits to the advice that can be

given on dynamic visual presentations in a printed textbook.

As in the earlier editions, the guidance on writing focuses on research, but is

intended to be broadly applicable to general technical and professional communi-

cation. Likewise, the guidance on the practice of research has wider lessons; for

example, a practitioner trying a new algorithm or explaining to colleagues why one

solution is preferable to another should be confident that the arguments are built on

robust foundations. And, while this edition has a stronger emphasis on the doing of

v

�

vi

Preface

research than did the first two, no topic has been removed; there is additional

material on research, but the guidance on writing has not been taken away. I can no

longer describe the book as brief, however!

Since the first edition appeared, there have been many changes in the culture of

research, and these continue to develop. Physical paper is slowly vanishing as a

publication medium, and traditional publishers are being challenged by a range of

open-access models. Academic technical reports, already rare a decade ago, have

more or less vanished, while online preprint archives have become a key part of the

research ecosystem. It now seems to be rare that a spoken presentation is truly

unprofessional, whereas in the 1990s many talks were unendurably awful. The

growth in the use of good tools for presentations has been a key factor in this

change.

Some cultural changes are less positive. A decade ago, I reported that many talks

did not have a clear message and were merely a compilation of clever visuals, and

that a well-described algorithm had become a welcome, rare exception; both these

trends have persisted. Also, while the globalization of English has brought

unquestionable benefits to international communication and collaboration, it means

that today many papers are written, refereed, and published without passing through

the hands of someone who is skilled in the language, so that even experienced

researchers occasionally produce work that is far too hard to understand. The Web

provides easy access to literature, but perhaps the necessity of using a library

imposed a discipline that is now lacking, as past work appears to be increasingly

neglected. Some issues concern the integrity of the scientific enterprise itself, such

as the growing number of venues that publish work that doesn’t meet even the most

rudimentary standards.

The perspectives of all scientists are shaped by the research environments in

which they work. My research has involved some theoretical studies, but the bulk

of my work has been experimental. I appreciate theoretical work for its elegance,

yet find it sterile when it is too detached from practical value. While experimental

work can be ad hoc, it can also be deeply satisfying, with the rewards of probing the

space of possible algorithms and producing technology that can be applied to the

things we do in practice. My perspective on research comes from this background,

as does the use of experimental work as examples in this book (an approach that is

also justified by the fact that such work is generally easier to outline than is a

theoretical contribution). But that doesn’t mean that my opinions are simply private

biases. They are—I hope!—the considered views of a scientist with experience of

different kinds of research.

For this new edition, William Webber and Anthony Wirth redrafted some sec-

tions, wrote new text, and helped guide the revisions in areas where I am inexpert; I

am particularly grateful for their contributions to the chapters on mathematics,

algorithms, experiments, and statistics. These sections now represent a consolida-

tion of views, though I have retained the use of I and my rather than we and our.

Both William and Tony are long-term colleagues; I’ve appreciated testing my views

against theirs, and I think this book is stronger for it. Another new contributor is

�

Preface

vii

Richard Zanibbi, whose suggestions for additional exercises I have gratefully

incorporated.

Many other people helped with this book in one way or another. For the first

edition, special thanks are due to Alistair Moffat, who contributed to the chapters on

figures, algorithms, editing, writing up, and reviewing. Another notable collaborator

has been Paul Gruba, my co-author on our two texts on thesis writing skills, How

To Write A Better Thesis and its prequel, How To Write A Better Minor Thesis.

With feedback from friends, colleagues, and readers for over 20 years, the list of

people who have influenced this book is large; particular thanks are due to Philip

Dart, Gill Dobbie, Michael Fuller, Evan Harris, Ian Shelley, Milad Shokouhi, Saiad

Tagaghoghi, James Thom, Rodney Topor, and Hugh Williams. I also thank my

research students; the hundreds of students who have participated in my research

methods lectures; and the many readers who pointed out mistakes or made helpful

suggestions.

Many thanks are due to my editor for the second and third editions, Beverley

Ford, for her patience during the procrastination, prevarication, and prevalent

preponderance of passivity that led to the long delay between editions. Thanks also

to the Springer staff who worked on the final editing and production, in particular

James Robinson. And, finally, thanks to my partner, Carolyn, for well lots of stuff.

Melbourne, Australia, September 2014

Justin Zobel

�

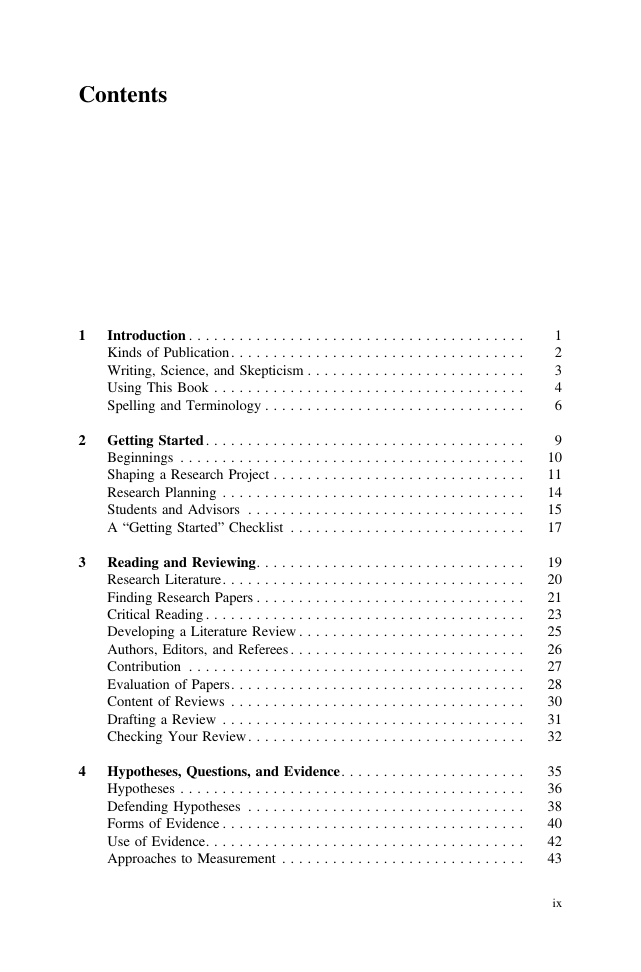

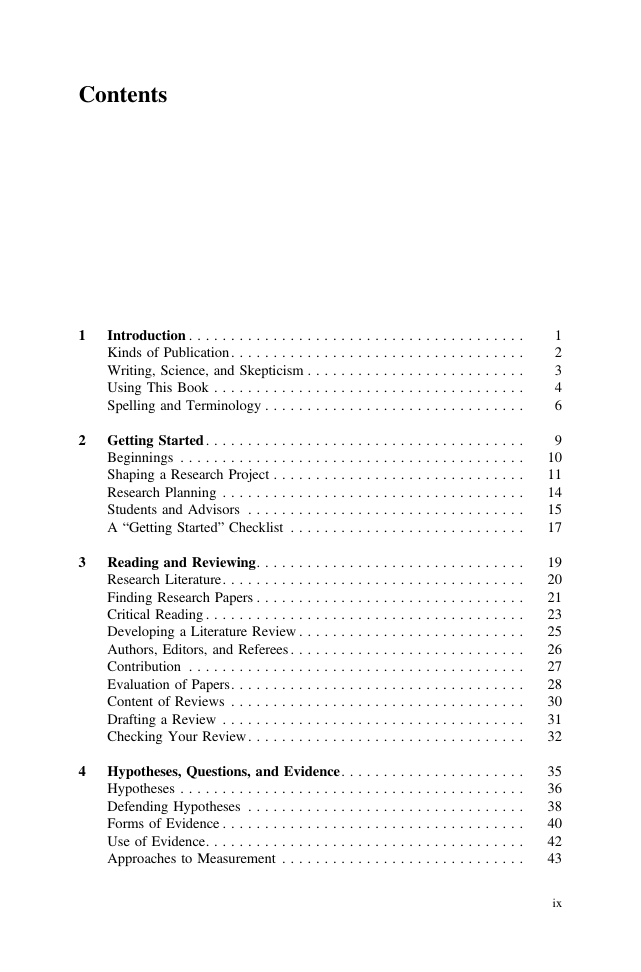

Contents

1

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Kinds of Publication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Writing, Science, and Skepticism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Using This Book . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Spelling and Terminology . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2 Getting Started . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Beginnings . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Shaping a Research Project . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Research Planning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Students and Advisors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

A “Getting Started” Checklist . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3

Reading and Reviewing. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Research Literature. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Finding Research Papers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Critical Reading . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Developing a Literature Review . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Authors, Editors, and Referees . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Contribution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Evaluation of Papers. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Content of Reviews . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Drafting a Review . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Checking Your Review . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4 Hypotheses, Questions, and Evidence. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Hypotheses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Defending Hypotheses . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Forms of Evidence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Use of Evidence. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Approaches to Measurement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

2

3

4

6

9

10

11

14

15

17

19

20

21

23

25

26

27

28

30

31

32

35

36

38

40

42

43

ix

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc