BP Statistical Review

of World Energy

2019 | 68th edition

�

Contents

Renewable energy

51 Renewables consumption

52 Generation by source

53 Biofuels production

For 66 years, the BP Statistical Review of World

Energy has provided high-quality objective and

globally consistent data on world energy markets.

The review is one of the most widely respected

and authoritative publications in the field of energy

Electricity

economics, used for reference by the media,

54 Generation

academia, world governments and energy

56 Generation by fuel

companies. A new edition is published every June.

CO2 Carbon

57 Carbon dioxide emissions

Natural gas

30 Reserves

32 Production

34 Consumption

37 Prices

38 Trade movements

Coal

42 Reserves

44 Production

45 Consumption

47 Prices and trade movements

Discover more online

Introduction

1 Group chief executive’s introduction

2 2018 at a glance

3 Group chief economist’s analysis

Primary energy

8 Consumption

9 Consumption by fuel

12 Consumption per capita

Oil

14 Reserves

16 Production

20 Consumption

24 Prices

26 Refining

28 Trade movements

All the tables and charts found in the latest printed

edition are available at bp.com/statisticalreview

plus a number of extras, including:

•

Nuclear energy

Hydroelectricity

48 Consumption

The energy charting tool – view

predetermined reports or chart specific data

according to energy type, region, country

and year.

Historical data from 1965 for many sections.

49 Consumption

Additional data for refined oil production

demand, natural gas, coal, hydroelectricity,

nuclear energy and renewables.

PDF versions and PowerPoint slide packs of

the charts, maps and graphs, plus an Excel

workbook of the data.

Regional and country factsheets.

Videos and speeches.

•

•

•

•

•

Key minerals

58 Production

59 Reserves

59 Prices

Appendices

60 Approximate conversion factors

60 Definitions

61 More information

Discover more online

All the tables and charts found in the printed edition are available

at bp.com/statisticalreview plus a number of extras, including:

Energy Outlook

Watch the BP Energy Outlook 2017 video,

containing our projections of long-term energy

trends to 2035. Download the booklet and

presentation materials at bp.com/energyoutlook

� The energy charting tool – view predetermined reports or chart

specific data according to energy type, region, country and year.

Join the conversation

#BPstats

Download the BP World Energy app

Explore the world of energy from your tablet or smartphone.

Customize charts and perform the calculations. Review

the data online and offline. Download the app for free from

the Apple App Store and Google play store.

� Historical data from 1965 for many sections. Additional

Download the BP World Energy app

country and regional coverage for all consumption tables.

� Additional data for refined oil production demand, natural gas, coal,

Explore the world of energy from your tablet or

smartphone. Customize charts and perform the

calculations. Review the data online and offline.

Download the app for free from the Apple

� PDF versions and PowerPoint slide packs of the charts, maps

App Store and Google play store.

hydroelectricity, nuclear energy and renewables.

and graphs, plus an Excel workbook and database format of the data.

� Regional and country factsheets.

� Videos and speeches.

Disclaimer

The data series for proved oil and gas reserves in BP Statistical Review of World Energy June 2017 does not necessarily

meet the definitions, guidelines and practices used for determining proved reserves at company level, for instance, as

published by the US Securities and Exchange Commission, nor does it necessarily represent BP’s view of proved

reserves by country. Rather, the data series has been compiled using a combination of primary official sources and

third-party data.

�

Group chief executive’s introduction

The developments documented in this year’s Statistical Review highlight a

critical challenge facing the global power sector. Power demand increased

even more strongly than overall energy demand in 2018, as the world

continued to electrify. But this shift towards greater electrification can play

an important part in the energy transition only if it is accompanied by a

decarbonization of the power sector.

Despite the continuing rapid growth in renewable energy last year, it

provided only a third of the required increase in power generation, with coal

providing a broadly similar contribution. Indeed, the increasing use of coal

within the power sector is estimated to have more than accounted for the

entire growth of global coal consumption last year.

Overall, the electric power sector is estimated to have absorbed around half

of the growth in primary energy in 2018 and accounted for around half of the

increase in carbon emissions.

Decarbonizing the power sector while also meeting the rapidly expanding

demand for power, particularly in the developing world, is perhaps the single

most important challenge facing the global energy system over the next

20 years. Renewable energy has a vital role to play in meeting that challenge.

But it is unlikely to be able to do so on its own. A variety of different

technologies and fuels are likely to be required, including extensive coal-to-

gas switching and the widespread deployment of carbon capture, use and

storage (CCUS). As I have said before, this is not a race to renewables, it is

a race to reduce carbon emissions across many fronts.

Our industry, and society more generally, face significant challenges as

we navigate the transition to a low carbon energy system. That will require

understanding and judgement, both of which rely on the kind of objective

data and analysis found in the Statistical Review. We are proud of the role

that the BP Statistical Review has played in informing public debate over

the past 68 years and I hope that you find it a useful resource for your

own discussions and deliberations.

Let me conclude by thanking BP’s economics team and all those who

have helped us prepare this Review – particularly those governments and

statistical agencies around the world who have contributed their official data

again this year. Thank you for your continuing co-operation and transparency.

Bob Dudley

Group chief executive

June 2019

1

Welcome to the BP Statistical Review of

World Energy, which records the events of

2018: a year in which there was a growing

divide between societal demands for an

accelerated transition to a low carbon energy

system and the actual pace of progress.

In particular, the data compiled in this year’s Review suggest that in 2018,

global energy demand and carbon emissions from energy use grew at their

fastest rate since 2010/11, moving even further away from the accelerated

transition envisaged by the Paris climate goals.

BP’s economics team estimate that much of the rise in energy growth

last year can be traced back to weather-related effects, as families and

businesses increased their demand for cooling and heating in response to

an unusually large number of hot and cold days. The acceleration in carbon

emissions was the direct result of this increased energy consumption.

Even if these weather effects are short-lived, such that the growth in energy

demand and carbon emissions slow over the next few years, there seems

little doubt that the current pace of progress is inconsistent with the Paris

climate goals. The world is on an unsustainable path: the longer carbon

emissions continue to rise, the harder and more costly will be the eventual

adjustment to net-zero carbon emissions. Yet another year of growing

carbon emissions underscores the urgency for the world to change.

The Statistical Review provides a timely and objective insight into those

developments and how that change can begin to be achieved.

The strength in energy consumption was reflected across all the fuels,

many of which grew more strongly than their recent historical averages.

This acceleration was particularly pronounced for natural gas, which grew

at one of its fastest rates for over 30 years, accounting for over 40% of the

growth in primary energy. On the supply side, the data for 2018 reinforced

the central importance of the US shale revolution. Remarkably, the US

recorded the largest ever annual increases by any country in both oil and

natural gas production last year, with the vast majority of both increases

coming from onshore shale plays. At the same time, renewable energy,

led by wind and solar power, continued to grow far more rapidly than any

other form of energy.

BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019�

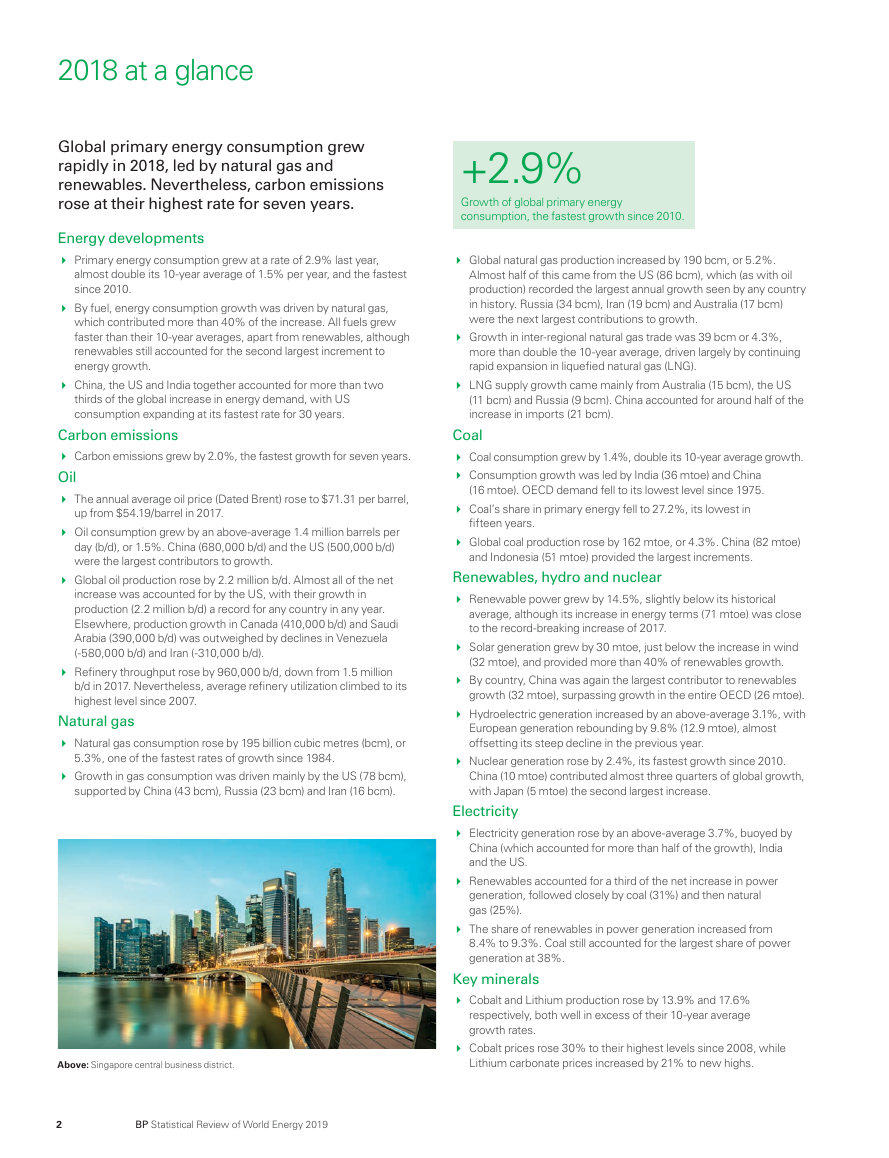

2018 at a glance

Global primary energy consumption grew

rapidly in 2018, led by natural gas and

renewables. Nevertheless, carbon emissions

rose at their highest rate for seven years.

Energy developments

� Primary energy consumption grew at a rate of 2.9% last year,

almost double its 10-year average of 1.5% per year, and the fastest

since 2010.

� By fuel, energy consumption growth was driven by natural gas,

which contributed more than 40% of the increase. All fuels grew

faster than their 10-year averages, apart from renewables, although

renewables still accounted for the second largest increment to

energy growth.

� China, the US and India together accounted for more than two

thirds of the global increase in energy demand, with US

consumption expanding at its fastest rate for 30 years.

Carbon emissions

� Carbon emissions grew by 2.0%, the fastest growth for seven years.

Oil

� The annual average oil price (Dated Brent) rose to $71.31 per barrel,

up from $54.19/barrel in 2017.

� Oil consumption grew by an above-average 1.4 million barrels per

day (b/d), or 1.5%. China (680,000 b/d) and the US (500,000 b/d)

were the largest contributors to growth.

� Global oil production rose by 2.2 million b/d. Almost all of the net

increase was accounted for by the US, with their growth in

production (2.2 million b/d) a record for any country in any year.

Elsewhere, production growth in Canada (410,000 b/d) and Saudi

Arabia (390,000 b/d) was outweighed by declines in Venezuela

(-580,000 b/d) and Iran (-310,000 b/d).

� Refinery throughput rose by 960,000 b/d, down from 1.5 million

b/d in 2017. Nevertheless, average refinery utilization climbed to its

highest level since 2007.

Natural gas

� Natural gas consumption rose by 195 billion cubic metres (bcm), or

5.3%, one of the fastest rates of growth since 1984.

� Growth in gas consumption was driven mainly by the US (78 bcm),

supported by China (43 bcm), Russia (23 bcm) and Iran (16 bcm).

Above: Singapore central business district.

2

+2.9%

Growth of global primary energy

consumption, the fastest growth since 2010.

� Global natural gas production increased by 190 bcm, or 5.2%.

Almost half of this came from the US (86 bcm), which (as with oil

production) recorded the largest annual growth seen by any country

in history. Russia (34 bcm), Iran (19 bcm) and Australia (17 bcm)

were the next largest contributions to growth.

� Growth in inter-regional natural gas trade was 39 bcm or 4.3%,

more than double the 10-year average, driven largely by continuing

rapid expansion in liquefied natural gas (LNG).

� LNG supply growth came mainly from Australia (15 bcm), the US

(11 bcm) and Russia (9 bcm). China accounted for around half of the

increase in imports (21 bcm).

Coal

� Coal consumption grew by 1.4%, double its 10-year average growth.

� Consumption growth was led by India (36 mtoe) and China

(16 mtoe). OECD demand fell to its lowest level since 1975.

� Coal’s share in primary energy fell to 27.2%, its lowest in

fifteen years.

� Global coal production rose by 162 mtoe, or 4.3%. China (82 mtoe)

and Indonesia (51 mtoe) provided the largest increments.

Renewables, hydro and nuclear

� Renewable power grew by 14.5%, slightly below its historical

average, although its increase in energy terms (71 mtoe) was close

to the record-breaking increase of 2017.

� Solar generation grew by 30 mtoe, just below the increase in wind

(32 mtoe), and provided more than 40% of renewables growth.

� By country, China was again the largest contributor to renewables

growth (32 mtoe), surpassing growth in the entire OECD (26 mtoe).

� Hydroelectric generation increased by an above-average 3.1%, with

European generation rebounding by 9.8% (12.9 mtoe), almost

offsetting its steep decline in the previous year.

� Nuclear generation rose by 2.4%, its fastest growth since 2010.

China (10 mtoe) contributed almost three quarters of global growth,

with Japan (5 mtoe) the second largest increase.

Electricity

� Electricity generation rose by an above-average 3.7%, buoyed by

China (which accounted for more than half of the growth), India

and the US.

� Renewables accounted for a third of the net increase in power

generation, followed closely by coal (31%) and then natural

gas (25%).

� The share of renewables in power generation increased from

8.4% to 9.3%. Coal still accounted for the largest share of power

generation at 38%.

Key minerals

� Cobalt and Lithium production rose by 13.9% and 17.6%

respectively, both well in excess of their 10-year average

growth rates.

� Cobalt prices rose 30% to their highest levels since 2008, while

Lithium carbonate prices increased by 21% to new highs.

BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019�

Group chief economist’s analysis

Primary energy

Contribution to primary energy growth in 2018

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

34%

20%

15%

10%

China

US

India

Other

Developing

Asia

Cumulative contribution (RHS)

100%

75%

50%

25%

0%

7%

5%

Russia Middle

East

3%

Africa

5%

Rest of

World

Contributions shown do not sum to 100% due to rounding

Energy in 2018: an unsustainable path

The Statistical Review of World Energy has been providing timely and

objective energy data for the past 68 years. In addition to the raw data, the

Statistical Review also provides a record of key energy developments and

events through time.

energy consumption. Coal demand (1.4%) also increased for the second

consecutive year, following three years of declines. Growth in renewable

energy (14.5%) eased back slightly relative to past trends although remained

by far the world’s fastest growing energy source.

My guess is that when our successors look back at Statistical Reviews

from around this period, they will observe a world in which there was

growing societal awareness and demands for urgent action on climate

change, but where the actual energy data continued to move stubbornly

in the wrong direction.

A growing mismatch between hopes and reality. In that context, I fear

– or perhaps hope – that 2018 will represent the year in which this

mismatch peaked.

Key features of 2018

The headline numbers are the rapid growth in energy demand and carbon

emissions. Global primary energy grew by 2.9% in 2018 – the fastest growth

seen since 2010. This occurred despite a backdrop of modest GDP growth

and strengthening energy prices.

At the same time, carbon emissions from energy use grew by 2.0%,

again the fastest expansion for many years, with emissions increasing by

around 0.6 gigatonnes. That’s roughly equivalent to the carbon emissions

associated with increasing the number of passenger cars on the planet

by a third.

What drove these increases in 2018? And how worried should we be?

Starting first with energy consumption. As I said, energy demand grew

by 2.9% last year. This growth was largely driven by China, US and India

which together accounted for around two thirds of the growth. Relative to

recent historical averages, the most striking growth was in the US, where

energy consumption increased by a whopping 3.5%, the fastest growth

seen for 30 years and in sharp contrast to the trend decline seen over the

previous 10 years.

The strength in energy consumption was pretty much reflected across

all the fuels, most of which grew more strongly than their historical

averages. This acceleration was particularly pronounced in natural gas

demand, which increased 5.3%, one of its strongest growth rates for

over 30 years, accounting for almost 45% of the entire growth in global

2.0%

Growth of carbon emissions from

energy use, the fastest for seven years.

In terms of why the growth in energy demand was so strong: a simple model

provides a way of gauging the extent of the surprise in this year’s energy

data. The model uses GDP growth and oil prices (as a proxy for energy prices)

to predict primary energy growth at a country level and then aggregates to

global energy. Although very simple, the framework is able to explain much

of the broad contours in energy demand over the past 20 years or so.

This framework predicts that the growth in energy demand should have

slowed a little last year, reflecting the slightly weaker economic backdrop

and the strengthening in energy prices. Instead, energy demand picked up

quite markedly.

Digging into the data further, it seems that much of the surprising strength in

energy consumption in 2018 may be related to weather effects. In particular,

there was an unusually large number of hot and cold days across many of

the world’s major demand centres last year, particularly in the US, China

and Russia, with the increased demand for cooling and heating services

helping to explain the strong growth in energy consumption in each of

these countries.

In the US, unusually, there was an increase in both heating and cooling

days (as defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration);

in past years, high numbers of heating days have tended to coincide with

low numbers of cooling days or vice versa. As a result, the increase in the

combined number of US heating and cooling days last year was its highest

since the 1950s, boosting US energy demand.

Global energy consumption growth

Annual change, %

6

4

2

0

-2

2000

2003

2006

2009

2012

2015

2018

Primary energy consumption

Predicted energy (with weather effects)*

Predicted energy (without weather effects)*

*These econometric models do not include Chinese energy intensive industries

3

BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019�

Energy demand and carbon emissions

Global energy consumption growth

Energy demand and

carbon emissions

Annual change, %

3%

Annual change, %

6%

4%

2%

0%

-2%

2%

1%

0%

-1%

2000 03

06

09

12

15

18

2012-2017

2018

Primary energy consumption

Predicted energy (with weather and

Chinese industry effects)

Primary energy

Carbon intensity

CO2 emissions

If we augment our framework to include a measure of heating and cooling

days for those countries for which data are available, this greatly reduces

the extent of the surprise in last year’s energy growth. Once these weather

effects are included, the growth in energy demand in 2018 still looks a

little stronger than expected, but more striking is the surprising weakness

of demand growth in the period 2014-16, which is far lower than the

framework predicts.

As discussed in previous Statistical Reviews, much of this weakness

appears to stem from the pattern of Chinese economic growth during this

period, in particular the pronounced weakness of some of China’s most

energy-intensive sectors – iron, steel and cement – which account for around

a quarter of China’s energy consumption and greatly dampened overall

energy growth. At the time, I speculated that some of the slowing in these

sectors reflected the structural rebalancing of the Chinese economy towards

more consumer and service-facing sectors and so was likely to persist. But

I also noted that the scale of the slowdown suggested that some of it was

likely to be cyclical and would reverse over time. And indeed, that is what

began to happen in iron and steel in 2017 and gathered pace last year.

If we adjust the framework to also take account of movements in these key

Chinese industrial sectors, the over-prediction of energy growth in 2014-16

is greatly reduced, as is the remaining ‘unexplained’ strength of energy

demand in 2018. So, in answer to the question of why energy demand was

so strong in 2018: it appears that the strength was largely due to weather-

related effects – especially in the US, China and Russia – together with

a further unwinding of cyclical factors in China.

How does this growth in energy demand relate to the worrying acceleration

in carbon emissions?

Above: Thunder Horse South Expansion project in the US Gulf of Mexico.

4

To a very large extent, the growth in carbon emissions is simply a direct

consequence of the increase in energy growth. Relative to the average of

the previous five years, growth in energy demand was 1.5 percentage points

higher in 2018 and the growth in carbon emissions was 1.4 percentage

points higher. One led to the other as the improvement in the carbon

intensity of the fuel mix was similar to its recent average.

Finally, in terms of the headline data, what signal might the 2018 data contain

for the future?

I think this depends in large part on how you interpret the increasing number

of heating and cooling days last year. If this was just random variation, we

might expect weather effects in the future to revert to more normal levels,

allowing the growth in energy demand and carbon emissions to fall back.

On the other hand, if there is a link between the growing levels of carbon in

the atmosphere and the types of weather patterns observed in 2018 this

would raise the possibility of a worrying vicious cycle: increasing levels of

carbon leading to more extreme weather patterns, which in turn trigger

stronger growth in energy (and carbon emissions) as households and

businesses seek to offset their effects.

There are many people better qualified than I to make judgements on this.

But even if these weather effects are short lived, such that the growth

in energy demand and carbon emissions slow over the next few years,

the recent trends still feel very distant from the types of transition paths

consistent with meeting the Paris climate goals.

Hopes and reality.

So, in that sense, there are grounds for us to be worried.

Oil

2018 was another rollercoaster year for oil markets, with prices starting

the year on a steady upward trend, reaching the dizzying heights of

$85/bbl in October, before plunging in the final quarter to end the year

at close to $50/bbl.

Oil demand provided a relatively stable backdrop, continuing to grow robustly,

increasing 1.4 Mb/d last year. In an absolute sense, the growth in demand

was dominated by the developing world, with China (0.7 Mb/d]) and India

(0.3 Mb/d) accounting for almost two thirds of the global increase. But relative

to the past 10 years or so, the big outlier was the US, where oil demand grew

by 0.5 Mb/d in 2018, its largest increase for well over 10 years, boosted by

increased demand for ethane as new production capacity came on stream.

The increased importance of petrochemicals in driving oil demand growth

was also evident in the global product breakdown, with products most

closely related to petrochemicals (ethane, LPG and naphtha) accounting

for around half of the overall growth in demand last year.

Against this backdrop of steady demand growth, all the excitement

came from the supply side, where global production grew by a whopping

2.2 Mb/d, more than double its historical average. The vast majority of this

growth was driven by US production, which grew by 2.2 Mb/d – the largest

ever annual increase by a single country. Since 2012 and the onset of the tight

oil revolution, US production (including NGLs) has increased by over 7 Mb/d

– broadly equivalent to Saudi Arabia’s crude oil exports – an astonishing

increase which has transformed both the structure of the US economy and

global oil market dynamics. Largely as a consequence, US net oil imports

shrunk to less than 3 Mb/d last year, compared with over 12 Mb/d in 2005.

2.2 Mb/d

Growth of US oil production, the largest

ever annual increase by a single country.

BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019�

Oil production

Global oil production

Annual change, Mb/d

3.0

Largest annual increases

in oil production

Mb/d

2.5

2.0

1.0

0.0

-1.0

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0

2016

2017

2018

OPEC

Other World

Average

2005-15

US

US

2018

Saudi

Arabia

1991

US

2014

Saudi

Arabia

1973

Saudi

Arabia

1986

OPEC production fell by 0.3 Mb/d in 2018, with a marked increase in Saudi

Arabian production (0.4 Mb/d) offset by falls in Venezuela (-0.6 Mb/d) and

Iran (-0.3 Mb/d). But this year-on-year comparison doesn’t do justice to the

intra-year twists and turns in OPEC production.

The ride began in the first half of 2018 with the continuation of the OPEC+

agreement from December 2016. The OPEC+ group consistently overshot

their agreed production cuts during 2017 and this overshooting increased

further during the first half of 2018, largely reflecting continuing falls in

Venezuelan output. These production cuts helped push OECD inventories

below their five year moving average for the first time since the collapse in

oil prices in 2014.

The first major twist came in the middle of 2018: in response to falling

Venezuelan production and the US announcing in May its intention to

impose sanctions on all Iranian oil exports, the OPEC+ group in June

committed to achieving 100% compliance of their production cuts for

the group as a whole.

This commitment contained two important signals. First, given the extent to

which production was below the target level, it signalled the prospect of an

immediate increase in production. Second, it helped reduce the uncertainty

associated with the possibility of future disruptions to either Iranian

and Venezuelan production since the commitment to maintain “100%

compliance” in essence signalled the willingness of other members of the

OPEC+ group to offset any lost production.

As a result, between May and November of last year, net production by

the OPEC+ group increased by 900 Kb/d, despite Iranian and Venezuelan

production falling by a further 1 Mb/d. Job done. Or was it?

The problem with trying to stabilize oil markets is that there is always some

other pesky development that you hadn’t expected. Oil production by

Libya and Nigeria – neither of which were part of the OPEC+ agreement –

increased by more than 500 Kb/d between June and November of last year.

As a result, OECD inventories started to grow again. The growing sense of

excess supply was compounded by the US announcing in November that it

would grant temporary waivers for some imports of Iranian oil.

This triggered another twist: a new OPEC+ group was formed in December

of last year – this time excluding Iran and Venezuela, as well as Libya, but

78 bcm

Growth of US gas consumption,

a record high for any country.

including Nigeria – with a commitment to reduce production by 1.2 Mb/d

relative to October 2018 levels. After a slow start, by the spring of this year,

inventories have fallen back to around their five year average once again.

It’s tempting to interpret these twists and turns as indicative of OPEC’s

waning powers. But I’m not sure that’s the correct interpretation. The role

that OPEC+ played in more than offsetting the falls in Iranian and Venezuelan

output last year was very significant. For me, the twists and turns simply

reflect the difficulty of market management, especially in a world of record

supply growth in one part of the world and heightened geopolitical tensions

in others. It feels like the rollercoaster will run for some time to come.

Natural gas

2018 was a bonanza year for natural gas, with both global consumption and

production increasing by over 5%, one of the strongest growth rates in either

gas demand or output for over 30 years. The main actor here was the US,

accounting for almost 40% of global demand growth and over 45% of the

increase in production.

US gas production increased by 86 bcm, an increase of almost 12%, driven

by shale gas plays in Marcellus, Haynesville and Permian. Indeed, the US

achieved a unique double first last year, recording the single largest-ever

annual increases by any country in both oil and gas production – in case there

was any doubt: the US shale revolution is alive and kicking. The gains in

global gas production were supported by Russia (34 bcm), Iran (19 bcm) and

Australia (17 bcm).

Although some of the increase in US gas supplies was used to feed the

three new US LNG trains which came on stream last year, the majority

was used to quench the thirst of domestic demand. US gas consumption

increased by 78 bcm last year – roughly the same growth as the country

achieved over the previous six years. This exceptional strength appears to be

largely driven by the same weather-related effects, with rising demand for

space heating and cooling fuelling increased gas consumption, both directly,

and, more importantly, indirectly via growing power demand. The expansion

of gas consumption within the US power sector was further boosted by

almost 15 gigawatts of coal-fired generation capacity being retired last year.

Outside of the US, the growth in global gas demand was relatively

concentrated across three other countries: China (43 bcm), Russia (23 bcm)

and Iran (16 bcm), which together with the US, accounted for 80% of

global growth.

China gas consumption grew by an astonishing 18% last year. This strength

stemmed largely from a continuation of environmental policies encouraging

coal-to-gas switching in industry and buildings in order to improve local air

quality, together with robust growth in industrial activity during the first half

of the year.

Above: Birds eye view of the Shah Deniz Alpha platform in the Caspian Sea,

off the coast of Azerbaijan.

5

BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019�

Natural gas

Consumption and

production growth

Annual change,

bcm

200

Consumption

Production

150

100

50

0

Largest annual increases

in gas production

bcm

100

80

60

40

20

0

Average

2007-17

US

2018 Average

2007-17

2018

US

2018

Russia

2010

US

2014

USSR

1984

Russia

2017

China

Russia

Iran

Other

Global LNG supplies continued their rapid expansion last year, increasing by

almost 10% (37 bcm) as a number of new liquefaction plants in Australia,

US and Russia were either started or ramped up. For much of the year, the

strength of Asian gas demand, led by China, was sufficient to absorb these

increasing supplies. But a waning in the strength of Asian demand towards

the end of the year, combined with a mini-surge in LNG exports, caused

prices to fall back and the differential between Asian and European spot

prices to narrow significantly.

Asian prices have fallen further in the first part of this year, towards the

bottom of the price band defined by US exporters’ full-cycle and operating

costs. The prospect of further rapid increases in LNG supplies this year

means there is a possibility of a first meaningful curtailment of some LNG

supply capacity. The extent of any eventual shut-in will depend importantly

on the European market, which acts as the de facto ‘market of last resort’ for

LNG supplies.

Europe’s gas demand contracted by a little over 2% (11 bcm) last year, but

this fall in demand was more than matched (-13 bcm) by continuing declines

in Europe’s ageing gas fields. The small increase in European gas imports

was largely met by LNG cargos diverted from Asia towards the end of the

year as the Asian premium over European prices almost disappeared.

Russian pipeline exports to Europe were largely unchanged on the year,

maintaining the record levels built up in recent years, although with a slight

decline in their share of Europe’s gas imports. A key factor determining the

role that Europe will play in balancing the global LNG market over coming

years will be the extent to which Russia seeks to maintain its market share.

Coal

2018 saw a further bounce back in coal – building on the slight pickup

seen in the previous year – with both consumption (1.4%) and production

(4.3%) increasing at their fastest rates for five years. This strength was

concentrated in Asia, with India and China together accounting for the vast

majority of the gains in both consumption and production.

The growth in coal demand was the second consecutive year of increases,

following three years of falling consumption. As a result, the peak in global

45%

China’s contribution to global

renewables growth, more than the

entire OECD combined.

6

coal consumption which many had thought had occurred in 2013 now looks

less certain: another couple of years of increases close to that seen last year

would take global consumption comfortably above 2013 levels.

The growth in coal consumption was more than accounted for by increasing

use in the power sector. This is despite continuing strong growth in

renewables: renewable energy increased by over 25% in both India and

China last year, which together accounted for around half of the global

growth in renewable energy. But even this was not sufficient to keep pace

with the strong gains in power demand, with coal being sucked into the

power sector as the balancing fuel.

This highlights an obvious but important point: even if renewables are

growing at truly exceptional rates, the pace of growth of power demand,

particularly in developing Asia, limits the pace at which the power sector

can decarbonize.

Power sector and renewable energy

The power sector needs to play a central role in any transition to a low

carbon energy system: it is the single largest source of carbon emissions

within the energy system; and it is where much of the lowest-hanging fruit

lie for reducing carbon emissions over the next 20 years. So, what happened

last year?

Global power demand grew by 3.7%, which is one of the strongest growth

rates seen for 20 years, absorbing around half of the growth in primary

energy. The developing world continued to drive the vast majority (81%)

of this growth, led by China and India who together accounted for around

two thirds of the increase in power demand. But the particularly strong

growth of power demand in 2018 owed much to the US, where power

demand grew by a bumper 3.7%, boosted by those weather effects.

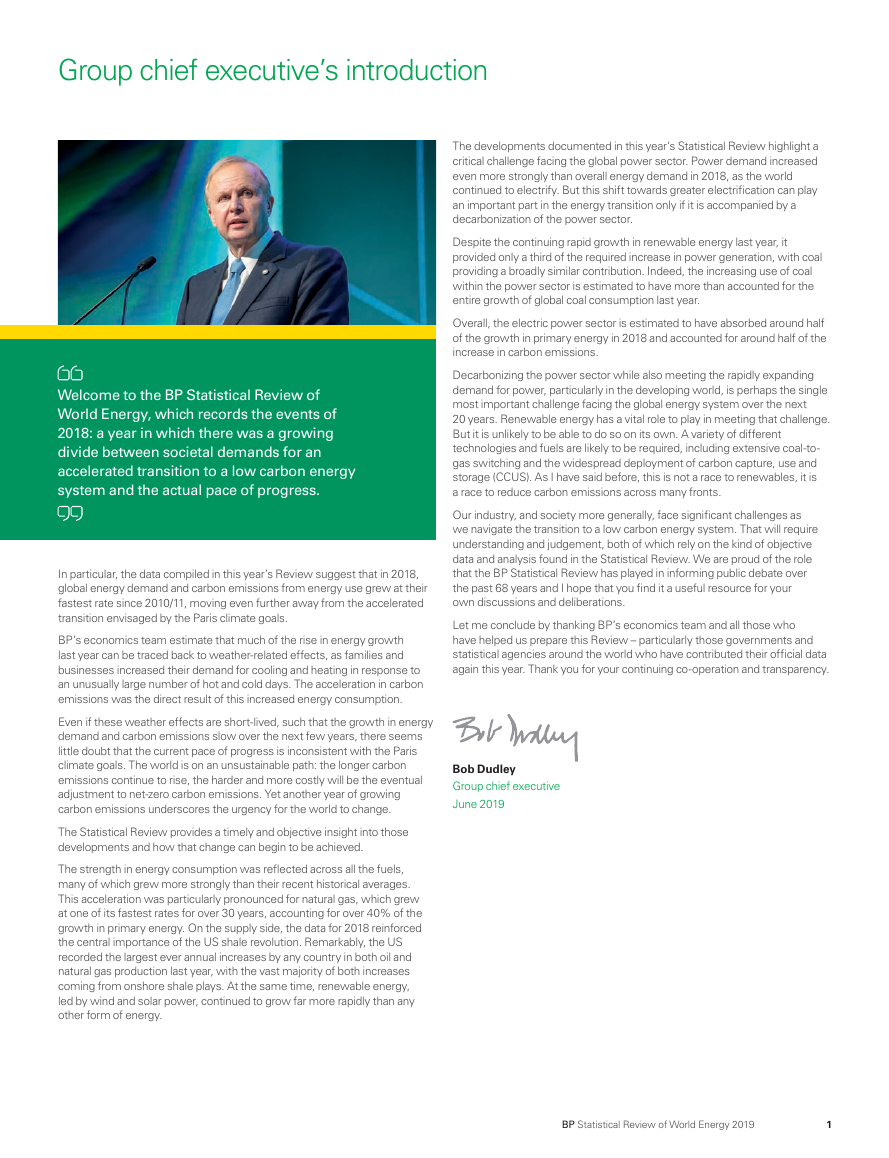

On the supply side, the growth in power generation was led by renewable

energy, which grew by 14.5%, contributing around a third of the growth;

followed by coal (3.0%) and natural gas (3.9%). China continued to lead

the way in renewables growth, accounting for 45% of the global growth in

renewable power generation, more than the entire OECD combined.

Renewable energy appears to be coming of age, but to repeat a point I made

last year, despite the increasing penetration of renewable power, the fuel

mix in the global power system remains depressingly flat, with the shares

of both non-fossil fuels (36%) and coal (38%) in 2018 unchanged from their

levels 20 years ago.

This persistence in the fuel mix highlights a point that the International

Energy Agency (IEA) and others have stressed recently; namely that a shift

towards greater electrification helps as a pathway to a lower carbon energy

system only if it goes hand-in-hand with a decarbonization of the power

sector. Electrification without decarbonizing power is of little use.

Above: Turbines at Goshen wind farm in Idaho Falls, US.

BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc