1

0

2

0

2

r

a

M

9

2

]

G

L

.

s

c

[

3

v

6

4

0

5

0

.

4

0

9

1

:

v

i

X

r

a

Generalizing from a Few Examples: A Survey on Few-Shot

Learning

YAQING WANG, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology and Baidu Research

QUANMING YAO∗, 4Paradigm Inc.

JAMES T. KWOK, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

LIONEL M. NI, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

Machine learning has been highly successful in data-intensive applications, but is often hampered when the

data set is small. Recently, Few-Shot Learning (FSL) is proposed to tackle this problem. Using prior knowledge,

FSL can rapidly generalize to new tasks containing only a few samples with supervised information. In this

paper, we conduct a thorough survey to fully understand FSL. Starting from a formal definition of FSL, we

distinguish FSL from several relevant machine learning problems. We then point out that the core issue in

FSL is that the empirical risk minimizer is unreliable. Based on how prior knowledge can be used to handle

this core issue, we categorize FSL methods from three perspectives: (i) data, which uses prior knowledge to

augment the supervised experience; (ii) model, which uses prior knowledge to reduce the size of the hypothesis

space; and (iii) algorithm, which uses prior knowledge to alter the search for the best hypothesis in the given

hypothesis space. With this taxonomy, we review and discuss the pros and cons of each category. Promising

directions, in the aspects of the FSL problem setups, techniques, applications and theories, are also proposed

to provide insights for future research.1

CCS Concepts: • Computing methodologies → Artificial intelligence; Machine learning; Learning

paradigms.

Additional Key Words and Phrases: Few-Shot Learning, One-Shot Learning, Low-Shot Learning, Small Sample

Learning, Meta-Learning, Prior Knowledge

ACM Reference Format:

Yaqing Wang, Quanming Yao, James T. Kwok, and Lionel M. Ni. 2020. Generalizing from a Few Examples: A

Survey on Few-Shot Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 1, 1, Article 1 (March 2020), 34 pages. https://doi.org/10.

1145/3386252

1 INTRODUCTION

“Can machines think?” This is the question raised in Alan Turing’s seminal paper entitled “Comput-

ing Machinery and Intelligence” [134] in 1950. He made the statement that “The idea behind digital

∗Corresponding Author

1A list of references, which will be updated periodically, can be found at https://github.com/tata1661/FewShotPapers.git.

Authors’ addresses: Yaqing Wang, ywangcy@connect.ust.hk, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Hong

Kong University of Science and Technology, Business Intelligence Lab and National Engineering Laboratory of Deep

Learning Technology and Application, Baidu Research; Quanming Yao, yaoquanming@4paradigm.com, 4Paradigm Inc.;

James T. Kwok, jamesk@cse.ust.hk, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Hong Kong University of Science

and Technology; Lionel M. Ni, ni@ust.hk, Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Hong Kong University of

Science and Technology.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee

provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and

the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than ACM must be honored.

Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires

prior specific permission and/or a fee. Request permissions from permissions@acm.org.

© 2020 Association for Computing Machinery.

0360-0300/2020/3-ART1 $15.00

https://doi.org/10.1145/3386252

ACM Comput. Surv., Vol. 1, No. 1, Article 1. Publication date: March 2020.

�

1:2

Yaqing Wang, Quanming Yao, James T. Kwok, and Lionel M. Ni

computers may be explained by saying that these machines are intended to carry out any opera-

tions which could be done by a human computer”. In other words, the ultimate goal of machines

is to be as intelligent as humans. In recent years, due to the emergence of powerful computing

devices (e.g., GPU and distributed platforms), large data sets (e.g., ImageNet data with 1000 classes

[30]), advanced models and algorithms (e.g., convolutional neural networks (CNN) [73] and long

short-term memory (LSTM) [58]), AI speeds up its pace to be like humans and defeats humans

in many fields. To name a few, AlphaGo [120] defeats human champions in the ancient game of

Go; and residual network (ResNet) [55] obtains better classification performance than humans on

ImageNet. AI also supports the development of intelligent tools in many aspects of daily life, such

as voice assistants, search engines, autonomous driving cars, and industrial robots.

Albeit its prosperity, current AI techniques cannot rapidly generalize from a few examples.

The aforementioned successful AI applications rely on learning from large-scale data. In contrast,

humans are capable of learning new tasks rapidly by utilizing what they learned in the past. For

example, a child who learned how to add can rapidly transfer his knowledge to learn multiplication

given a few examples (e.g., 2 × 3 = 2 + 2 + 2 and 1 × 3 = 1 + 1 + 1). Another example is that given a

few photos of a stranger, a child can easily identify the same person from a large number of photos.

Bridging this gap between AI and humans is an important direction. It can be tackled by machine

learning, which is concerned with the question of how to construct computer programs that

automatically improve with experience [92, 94]. In order to learn from a limited number of examples

with supervised information, a new machine learning paradigm called Few-Shot Learning (FSL)

[35, 36] is proposed. A typical example is character generation [76], in which computer programs

are asked to parse and generate new handwritten characters given a few examples. To handle this

task, one can decompose the characters into smaller parts transferable across characters, and then

aggregate these smaller components into new characters. This is a way of learning like human [77].

Naturally, FSL can also advance robotics [26], which develops machines that can replicate human

actions. Examples include one-shot imitation [147], multi-armed bandits [33], visual navigation

[37], and continuous control [156].

Another classic FSL scenario is where examples with supervised information are hard or im-

possible to acquire due to privacy, safety or ethic issues. A typical example is drug discovery,

which tries to discover properties of new molecules so as to identify useful ones as new drugs [4].

Due to possible toxicity, low activity, and low solubility, new molecules do not have many real

biological records on clinical candidates. Hence, it is important to learn effectively from a small

number of samples. Similar examples where the target tasks do not have many examples include

FSL translation [65], and cold-start item recommendation [137]. Through FSL, learning suitable

models for these rare cases can become possible.

FSL can also help relieve the burden of collecting large-scale supervised data. For example,

although ResNet [55] outperforms humans on ImageNet, each class needs to have sufficient labeled

images which can be laborious to collect. FSL can reduce the data gathering effort for data-intensive

applications. Examples include image classification [138], image retrieval [130], object tracking [14],

gesture recognition [102], image captioning, visual question answering [31], video event detection

[151], language modeling [138], and neural architecture search [19].

Driven by the academic goal for AI to approach humans and the industrial demand for inexpensive

learning, FSL has drawn much recent attention and is now a hot topic. Many related machine

learning approaches have been proposed, such as meta-learning [37, 106, 114], embedding learning

[14, 126, 138] and generative modeling [34, 35, 113]. However, currently, there is no work that

provides an organized taxonomy to connect these FSL methods, explains why some methods work

while others fail, nor discusses the pros and cons of different approaches. Therefore, in this paper,

ACM Comput. Surv., Vol. 1, No. 1, Article 1. Publication date: March 2020.

�

Generalizing from a Few Examples: A Survey on Few-Shot Learning

1:3

we conduct a survey on the FSL problem. In contrast, the survey in [118] only focuses on concept

learning and experience learning for small samples.

Contributions of this survey can be summarized as follows:

• We give a formal definition on FSL, which naturally connects to the classic machine learning

definition in [92, 94]. The definition is not only general enough to include existing FSL works,

but also specific enough to clarify what the goal of FSL is and how we can solve it. This

definition is helpful for setting future research targets in the FSL area.

• We list the relevant learning problems for FSL with concrete examples, clarifying their

relatedness and differences with respect to FSL. These discussions can help better discriminate

and position FSL among various learning problems.

• We point out that the core issue of FSL supervised learning problem is the unreliable empirical

risk minimizer, which is analyzed based on error decomposition [17] in machine learning.

This provides insights to improve FSL methods in a more organized and systematic way.

• We perform an extensive literature review, and organize them in an unified taxonomy

from the perspectives of data, model and algorithm. We also present a summary of insights

and a discussion on the pros and cons of each category. These can help establish a better

understanding of FSL methods.

• We propose promising future directions for FSL in the aspects of problem setup, techniques,

applications and theories. These insights are based on the weaknesses of the current develop-

ment of FSL, with possible improvements to make in the future.

1.1 Organization of the Survey

The remainder of this survey is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an overview for FSL,

including its formal definition, relevant learning problems, core issue, and a taxonomy of existing

works in terms of data, model and algorithm. Section 3 is for methods that augment data to solve

FSL problem. Section 4 is for methods that reduce the size of hypothesis space so as to make FSL

feasible. Section 5 is for methods that alter the search strategy of algorithm to deal with the FSL

problem. In Section 6, we propose future directions for FSL in terms of problem setup, techniques,

applications and theories. Finally, the survey closes with conclusion in Section 7.

i =1 where I is small, and a testing set Dtest = {x

1.2 Notation and Terminology

Consider a learning task T , FSL deals with a data set D = {Dtrain, Dtest} consisting of a training set

Dtrain = {(xi , yi)}I

test}. Let p(x, y) be the ground-truth

joint probability distribution of input x and output y, and ˆh be the optimal hypothesis from x to

y. FSL learns to discover ˆh by fitting Dtrain and testing on Dtest. To approximate ˆh, the FSL model

determines a hypothesis space H of hypotheses h(·; θ)’s, where θ denotes all the parameters used

by h. Here, a parametric h is used, as a nonparametric model often requires large data sets, and

thus not suitable for FSL. A FSL algorithm is an optimization strategy that searches H in order to

find the θ that parameterizes the best h∗ ∈ H. The FSL performance is measured by a loss function

ℓ( ˆy, y) defined over the prediction ˆy = h(x; θ) and the observed output y.

2 OVERVIEW

In this section, we first provide a formal definition of the FSL problem in Section 2.1 with concrete

examples. To differentiate the FSL problem from relevant machine learning problems, we discuss

their relatedness and differences in Section 2.2. In Section 2.3, we discuss the core issue that makes

FSL difficult. Section 2.4 then presents a unified taxonomy according to how existing works handle

the core issue.

ACM Comput. Surv., Vol. 1, No. 1, Article 1. Publication date: March 2020.

�

1:4

Yaqing Wang, Quanming Yao, James T. Kwok, and Lionel M. Ni

2.1 Problem Definition

As FSL is a sub-area in machine learning, before giving the definition of FSL, let us recall how

machine learning is defined in the literature.

Definition 2.1 (Machine Learning [92, 94]). A computer program is said to learn from experience

E with respect to some classes of task T and performance measure P if its performance can improve

with E on T measured by P.

For example, consider an image classification task (T ), a machine learning program can improve

its classification accuracy (P) through E obtained by training on a large number of labeled images

(e.g., the ImageNet data set [73]). Another example is the recent computer program AlphaGo [120],

which has defeated the human champion in playing the ancient game of Go (T ). It improves its

winning rate (P) against opponents by training on a database (E) of around 30 million recorded

moves of human experts as well as playing against itself repeatedly. These are summarized in

Table 1.

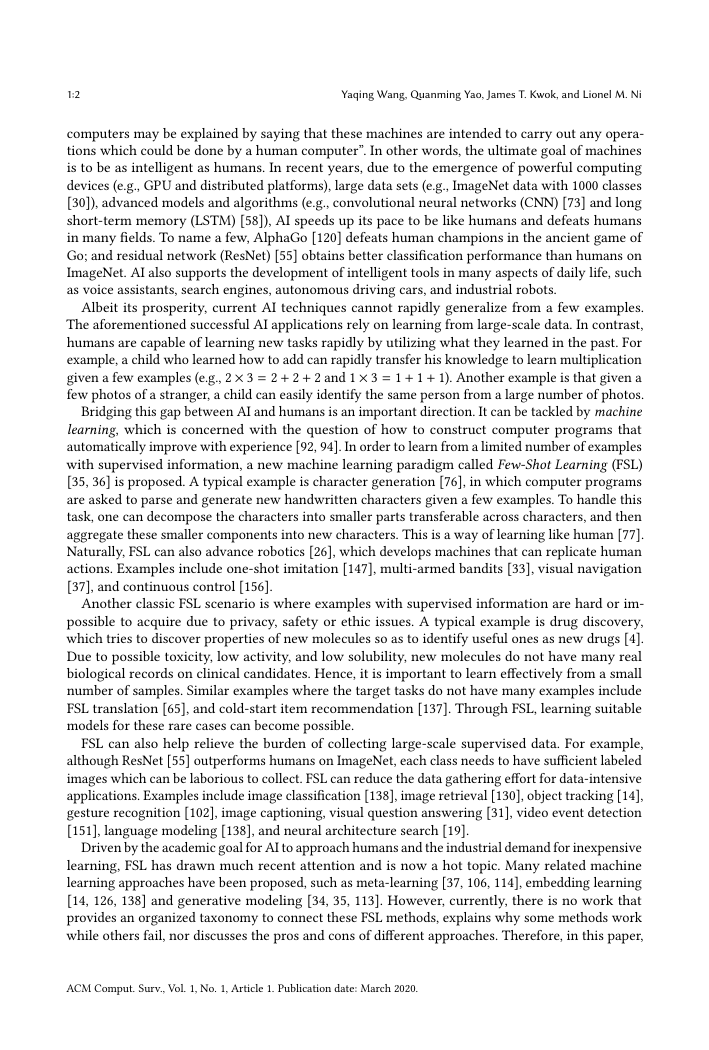

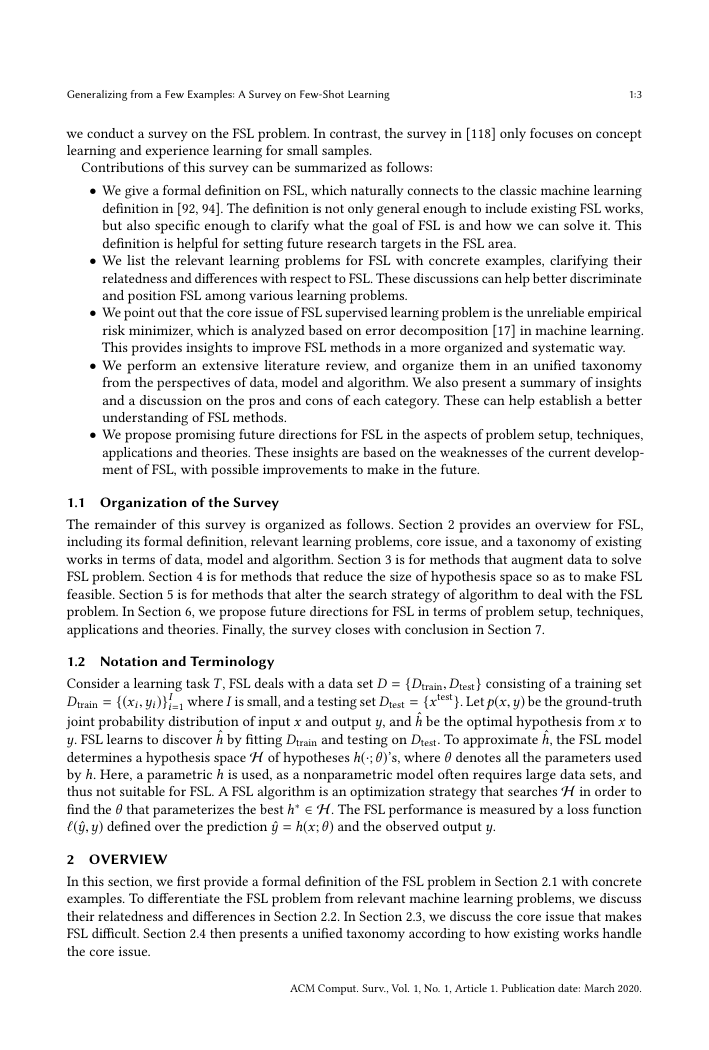

Table 1. Examples of machine learning problems based on Definition 2.1.

task T

experience E

image classification [73]

large-scale labeled images for each class

the ancient game of Go [120]

a database containing around 30 million recorded moves

of human experts and self-play records

performance P

classification

accuracy

winning rate

Typical machine learning applications, as in the examples mentioned above, require a lot of

examples with supervised information. However, as mentioned in the introduction, this may be

difficult or even not possible. FSL is a special case of machine learning, which targets at obtaining

good learning performance given limited supervised information provided in the training set Dtrain,

which consists of examples of inputs xi’s along with their corresponding output yi’s [15]. Formally,

we define FSL in Definition 2.2.

Definition 2.2. Few-Shot Learning (FSL) is a type of machine learning problems (specified by E,

T and P), where E contains only a limited number of examples with supervised information for the

target T .

Existing FSL problems are mainly supervised learning problems. Concretely, few-shot classification

learns classifiers given only a few labeled examples of each class. Example applications include

image classification [138], sentiment classification from short text [157] and object recognition

[35]. Formally, using notations from Section 1.2, few-shot classification learns a classifier h which

predicts label yi for each input xi. Usually, one considers the N -way-K-shot classification [37, 138],

in which Dtrain contains I = KN examples from N classes each with K examples. Few-shot regression

[37, 156] estimates a regression function h given only a few input-output example pairs sampled

from that function, where output yi is the observed value of the dependent variable y, and xi is

the input which records the observed value of the independent variable x. Apart from few-shot

supervised learning, another instantiation of FSL is few-shot reinforcement learning [3, 33], which

targets at finding a policy given only a few trajectories consisting of state-action pairs.

We now show three typical scenarios of FSL (Table 2):

• Acting as a test bed for learning like human. To move towards human intelligence, it is vital

that computer programs can solve the FSL problem. A popular task (T ) is to generate samples

of a new character given only a few examples [76]. Inspired by how humans learn, the

ACM Comput. Surv., Vol. 1, No. 1, Article 1. Publication date: March 2020.

�

Generalizing from a Few Examples: A Survey on Few-Shot Learning

1:5

computer programs learn with the E consisting of both the given examples with supervised

information and pre-trained concepts such as parts and relations as prior knowledge. The

generated characters are evaluated through the pass rate of visual Turing test (P), which

discriminates whether the images are generated by humans or machines. With this prior

knowledge, computer programs can also learn to classify, parse and generate new handwritten

characters with a few examples like humans.

• Learning for rare cases. When obtaining sufficient examples with supervised information

is hard or impossible, FSL can learn models for the rare cases. For example, consider a

drug discovery task (T ) which tries to predict whether a new molecule has toxic effects [4].

The percentage of molecules correctly assigned as toxic or non-toxic (P) improves with E

obtained by both the new molecule’s limited assay, and many similar molecules’ assays as

prior knowledge.

• Reducing data gathering effort and computational cost. FSL can help relieve the burden of

collecting large number of examples with supervised information. Consider few-shot image

classification task (T ) [35]. The image classification accuracy (P) improves with the E obtained

by a few labeled images for each class of the target T , and prior knowledge extracted from

the other classes (such as raw images to co-training). Methods succeed in this task usually

have higher generality. Therefore, they can be easily applied for tasks of many samples.

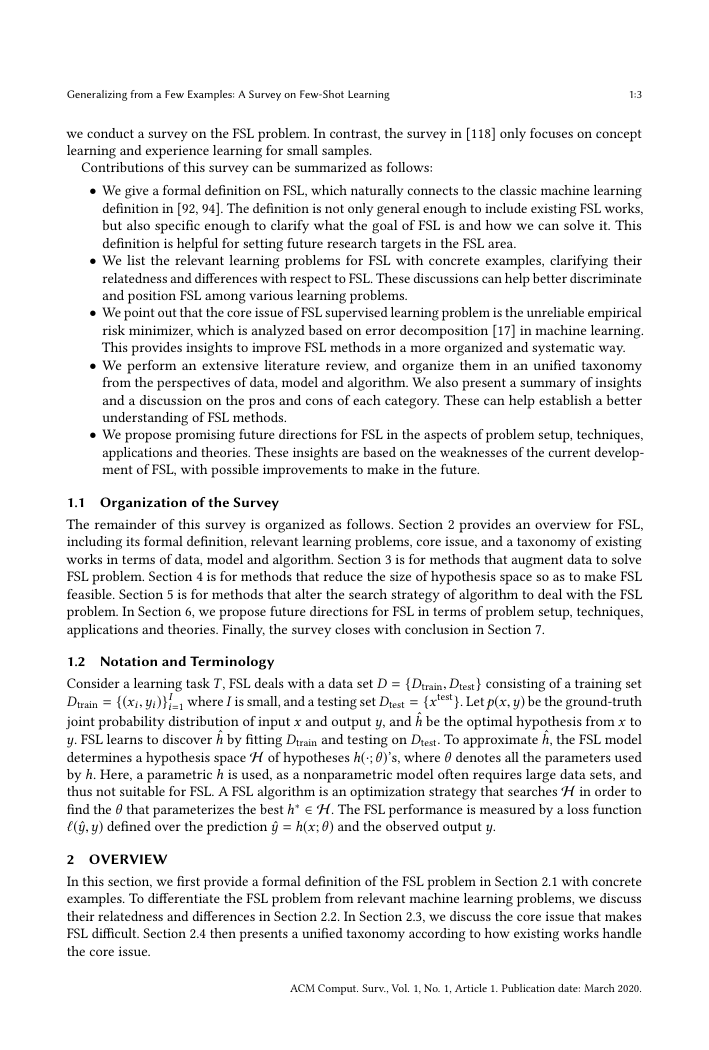

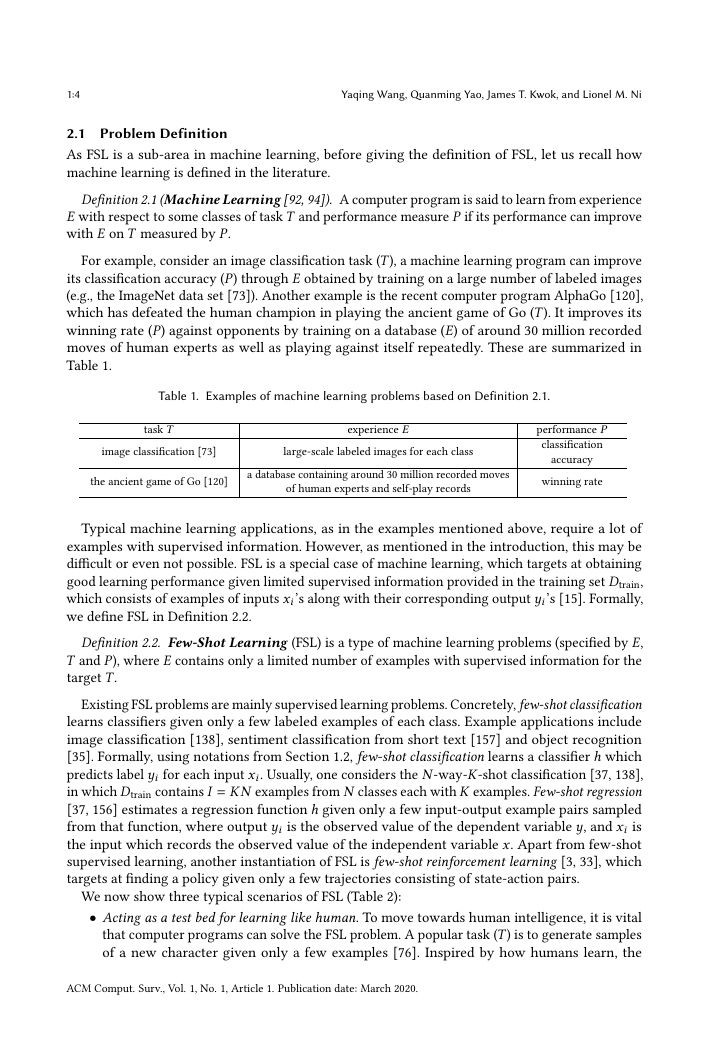

Table 2. Three FSL examples based on Definition 2.2.

task T

character generation [76]

drug toxicity discovery [4]

image classification [70]

supervised information

a few examples of new

character

new molecule’s limited

assay

a few labeled images for

each class of the target T

experience E

prior knowledge

pre-learned knowledge of

parts and relations

similar molecules’ assays

raw images of other classes,

or pre-trained models

performance P

pass rate of visual

Turing test

classification

accuracy

classification

accuracy

In comparison to Table 1, Table 2 has one extra column under “experience E" which is marked

as “prior knowledge". As E only contains a few examples with supervised information directly

related to T , it is natural that common supervised learning approaches often fail on FSL problems.

Therefore, FSL methods make the learning of target T feasible by combining the available supervised

information in E with some prior knowledge, which is “any information the learner has about the

unknown function before seeing the examples" [86]. One typical type of FSL methods is Bayesian

learning [35, 76]. It combines the provided training set Dtrain with some prior probability distribution

which is available before Dtrain is given [15].

Remark 1. When there is only one example with supervised information in E, FSL is called one-shot

learning [14, 35, 138]. When E does not contain any example with supervised information for the

target T , FSL becomes a zero-shot learning problem (ZSL) [78]. As the target class does not contain

examples with supervised information, ZSL requires E to contain information from other modalities

(such as attributes, WordNet, and word embeddings used in rare object recognition tasks), so as to

transfer some supervised information and make learning possible.

2.2 Relevant Learning Problems

In this section, we discuss some relevant machine learning problems. The relatedness and difference

with respect to FSL are clarified.

ACM Comput. Surv., Vol. 1, No. 1, Article 1. Publication date: March 2020.

�

1:6

Yaqing Wang, Quanming Yao, James T. Kwok, and Lionel M. Ni

• Weakly supervised learning [163] learns from experience E containing only weak supervision

(such as incomplete, inexact, inaccurate or noisy supervised information). The most relevant

problem to FSL is weakly supervised learning with incomplete supervision where only a small

amount of samples have supervised information. According to whether the oracle or human

intervention is leveraged, this can be further classified into the following:

– Semi-supervised learning [165], which learns from a small number of labeled samples and

(usually a large number of) unlabeled samples in E. Example applications are text and

webpage classification. Positive-unlabeled learning [81] is a special case of semi-supervised

learning, in which only positive and unlabeled samples are given. For example, to recom-

mend friends in social networks, we only know the users’ current friends according to the

friend list, while their relationships to other people are unknown.

– Active learning [117], which selects informative unlabeled data to query an oracle for

output y. This is usually used for applications where annotation labels are costly, such as

pedestrian detection.

By definition, weakly supervised learning with incomplete supervision includes only classifi-

cation and regression, while FSL also includes reinforcement learning problems. Moreover,

weakly supervised learning with incomplete supervision mainly uses unlabeled data as ad-

ditional information in E, while FSL leverages various kinds of prior knowledge such as

pre-trained models, supervised data from other domains or modalities and does not restrict

to using unlabeled data. Therefore, FSL becomes weakly supervised learning problem only

when prior knowledge is unlabeled data and the task is classification or regression.

• Imbalanced learning [54] learns from experience E with a skewed distribution for y. This

happens when some values of y are rarely taken, as in fraud detection and catastrophe

anticipation applications. It trains and tests to choose among all possible y’s. In contrast,

FSL trains and tests for y with a few examples, while possibly taking the other y’s as prior

knowledge for learning.

• Transfer learning [101] transfers knowledge from the source domain/task, where training

data is abundant, to the target domain/task, where training data is scarce. It can be used in

applications such as cross-domain recommendation, WiFi localization across time periods,

space and mobile devices. Domain adaptation [11] is a type of transfer learning in which the

source/target tasks are the same but the source/target domains are different. For example, in

sentiment analysis, the source domain data contains customer comments on movies, while the

target domain data contains customer comments on daily goods. Transfer learning methods

are popularly used in FSL [7, 82, 85], where the prior knowledge is transferred from the

source task to the few-shot task.

• Meta-learning [59] improves P of the new task T by the provided data set and the meta-

knowledge extracted across tasks by a meta-learner. Specifically, the meta-learner gradually

learns generic information (meta-knowledge) across tasks, and the learner generalizes the

meta-learner for a new task T using task-specific information. It has been successfully

applied in problems such as learning optimizers [5, 80], dealing with the cold-start problem

in collaborative filtering [137], and guiding policies by natural language [25]. Meta-learning

methods can be used to deal with the FSL problem. As will be shown in Sections 4 and 5, the

meta-learner is taken as prior knowledge to guide each specific FSL task. A formal definition

of meta-learning and how it is used for the FSL problem are provided in Appendix A.

2.3 Core Issue

In any machine learning problem, usually there are prediction errors and one cannot obtain perfect

predictions. In this section, we illustrate the core issue of FSL based on error decomposition in

ACM Comput. Surv., Vol. 1, No. 1, Article 1. Publication date: March 2020.

�

Generalizing from a Few Examples: A Survey on Few-Shot Learning

1:7

supervised machine learning [17, 18]. This analysis applies to FSL supervised learning including

classification and regression, and can also provide insights for understanding FSL reinforcement

learning.

2.3.1 Empirical Risk Minimization. Given a hypothesis h, we want to minimize its expected risk R,

which is the loss measured with respect to p(x, y). Specifically,

∫

R(h) =

ℓ(h(x), y) dp(x, y) = E[ℓ(h(x), y)].

As p(x, y) is unknown, the empirical risk (which is the average of sample losses over the training

set Dtrain of I samples)

I�

i =1

RI(h) =

1

I

ℓ(h(xi), yi),

is usually used as a proxy for R(h), leading to empirical risk minimization [94, 136] (with possibly

some regularizers). For illustration, let

• ˆh = arg minh R(h) be the function that minimizes the expected risk;

• h∗ = arg minh∈H R(h) be the function in H that minimizes the expected risk;

• hI = arg minh∈H RI(h) be the function in H that minimizes the empirical risk.

As ˆh is unknown, one has to approximate it by some h ∈ H. h∗ is the best approximation for ˆh in

H, while hI is the best hypothesis in H obtained by empirical risk minimization. For simplicity,

we assume that ˆh, h∗ and hI are unique. The total error can be decomposed as [17, 18]:

E[R(hI) − R( ˆh)] = E[R(h

∗) − R( ˆh)]

Eapp(H)

+ E[R(hI) − R(h

Eest(H , I)

∗)]

,

(1)

where the expectation is with respect to the random choice of Dtrain. The approximation error

Eapp(H) measures how close the functions in H can approximate the optimal hypothesis ˆh, and

the estimation error Eest(H , I) measures the effect of minimizing the empirical risk RI(h) instead of

the expected risk R(h) within H.

As shown, the total error is affected by H (hypothesis space) and I (number of examples in

Dtrain). In other words, learning to reduce the total error can be attempted from the perspectives of

(i) data, which provides Dtrain; (ii) model, which determines H; and (iii) algorithm, which searches

for the optimal hI ∈ H that fits Dtrain.

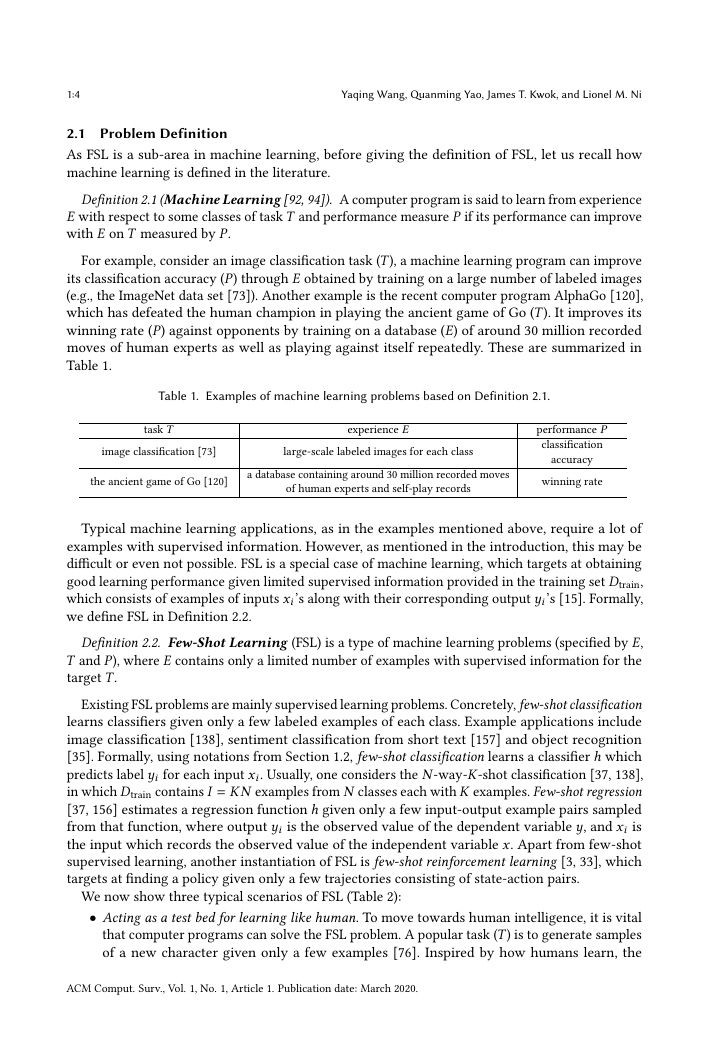

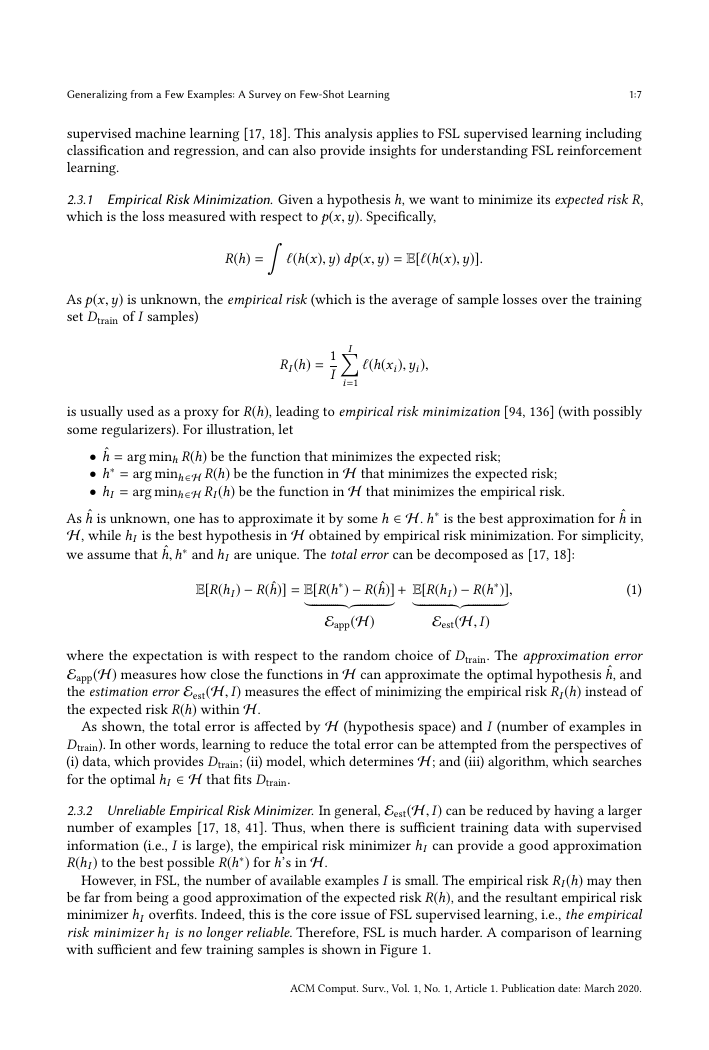

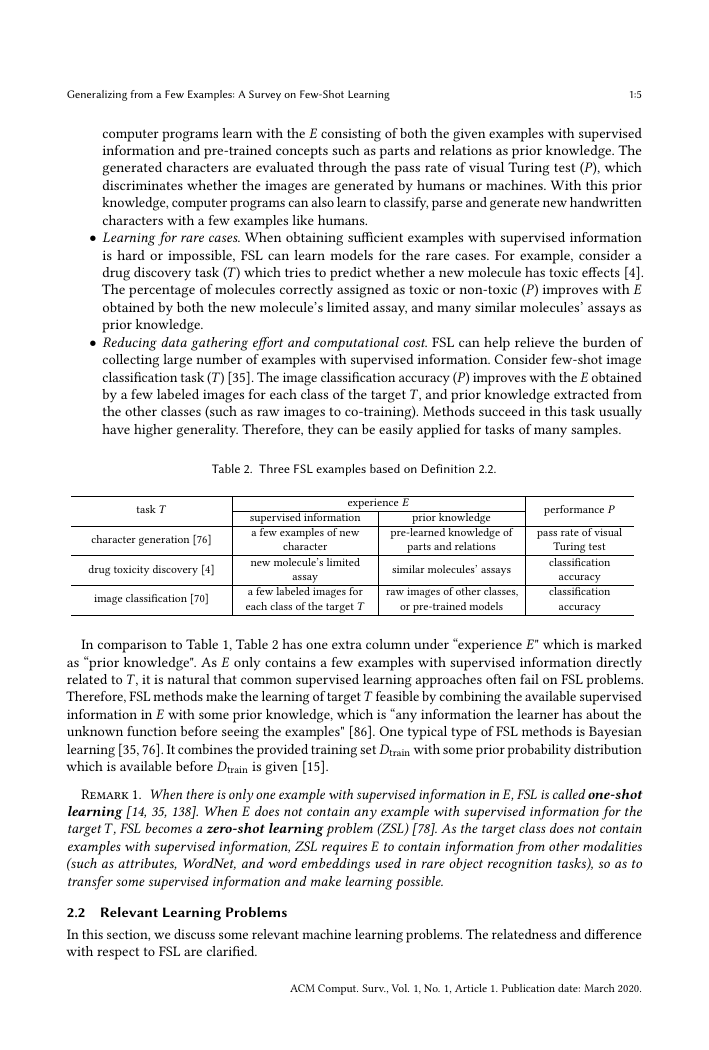

2.3.2 Unreliable Empirical Risk Minimizer. In general, Eest(H , I) can be reduced by having a larger

number of examples [17, 18, 41]. Thus, when there is sufficient training data with supervised

information (i.e., I is large), the empirical risk minimizer hI can provide a good approximation

R(hI) to the best possible R(h∗) for h’s in H.

However, in FSL, the number of available examples I is small. The empirical risk RI(h) may then

be far from being a good approximation of the expected risk R(h), and the resultant empirical risk

minimizer hI overfits. Indeed, this is the core issue of FSL supervised learning, i.e., the empirical

risk minimizer hI is no longer reliable. Therefore, FSL is much harder. A comparison of learning

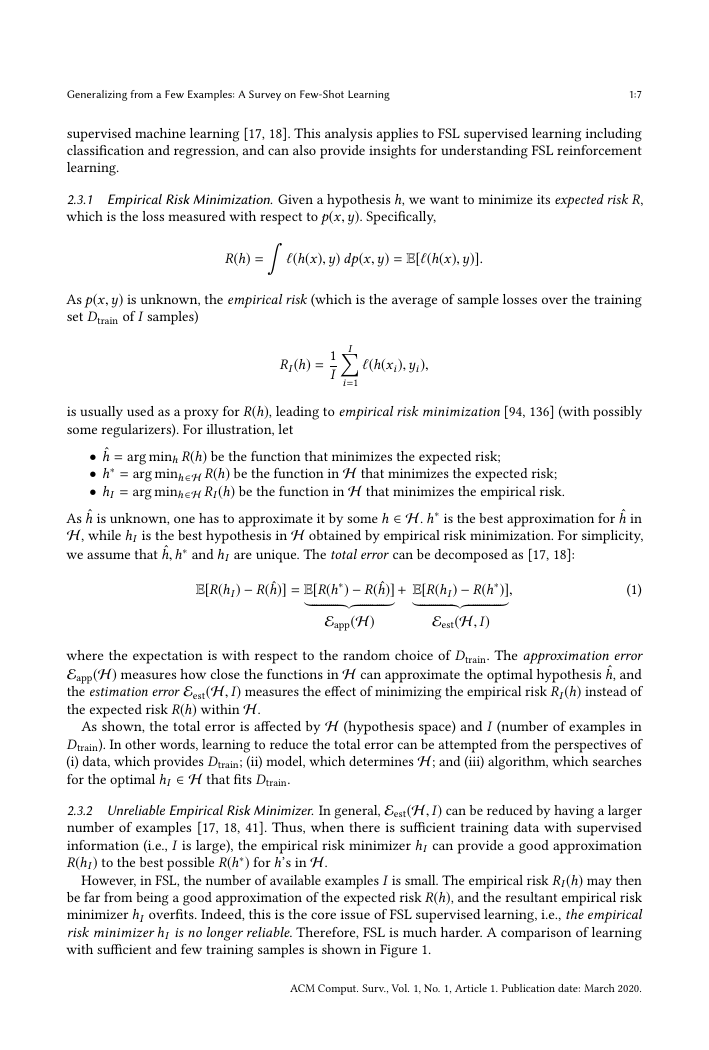

with sufficient and few training samples is shown in Figure 1.

ACM Comput. Surv., Vol. 1, No. 1, Article 1. Publication date: March 2020.

�

1:8

Yaqing Wang, Quanming Yao, James T. Kwok, and Lionel M. Ni

(a) Large I.

(b) Small I.

Fig. 1. Comparison of learning with sufficient and few training samples.

2.4 Taxonomy

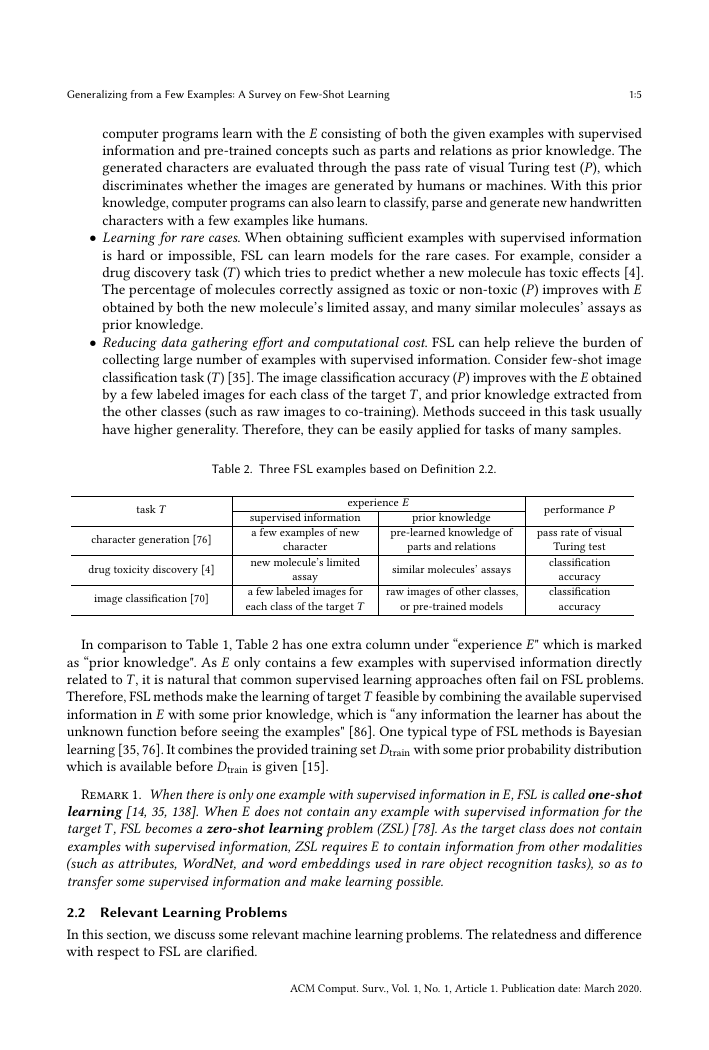

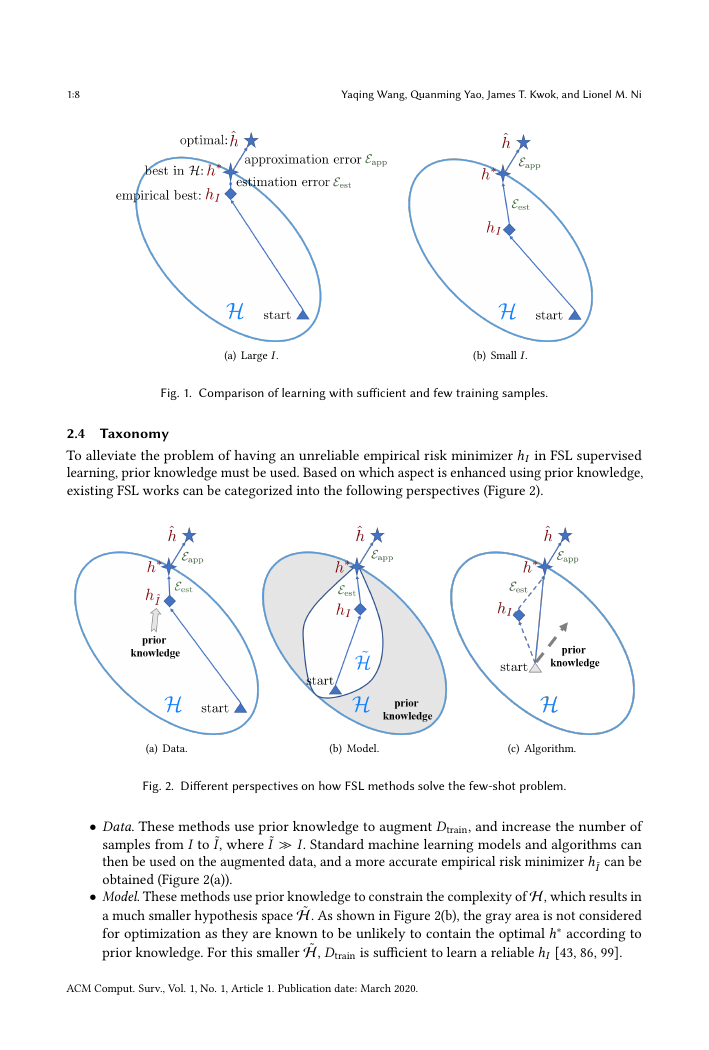

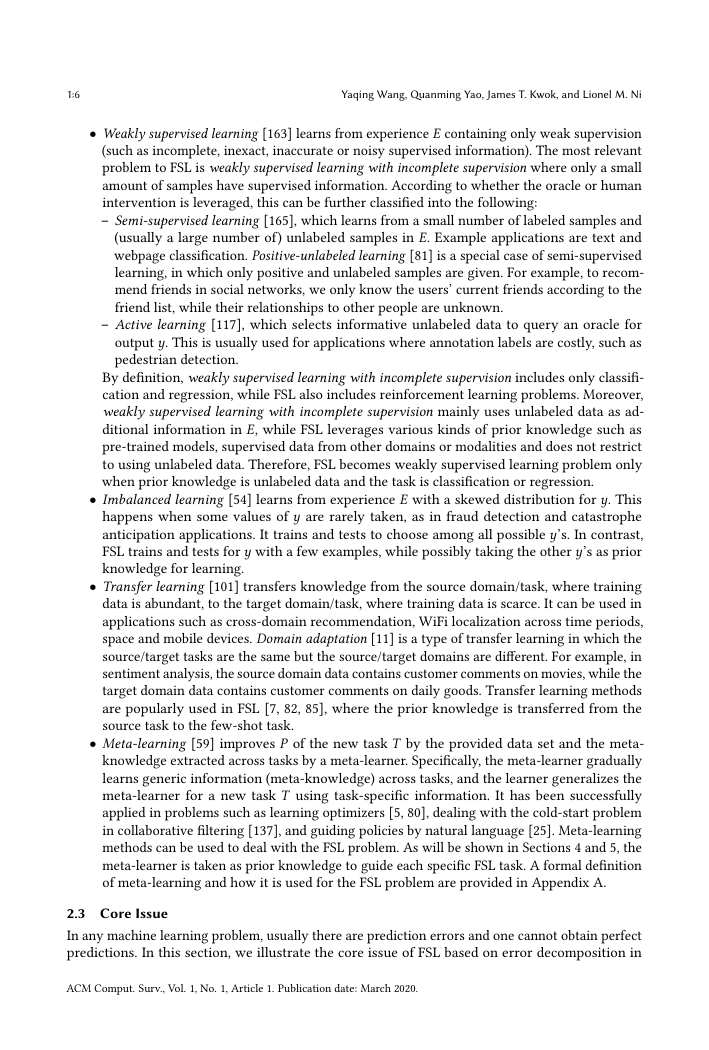

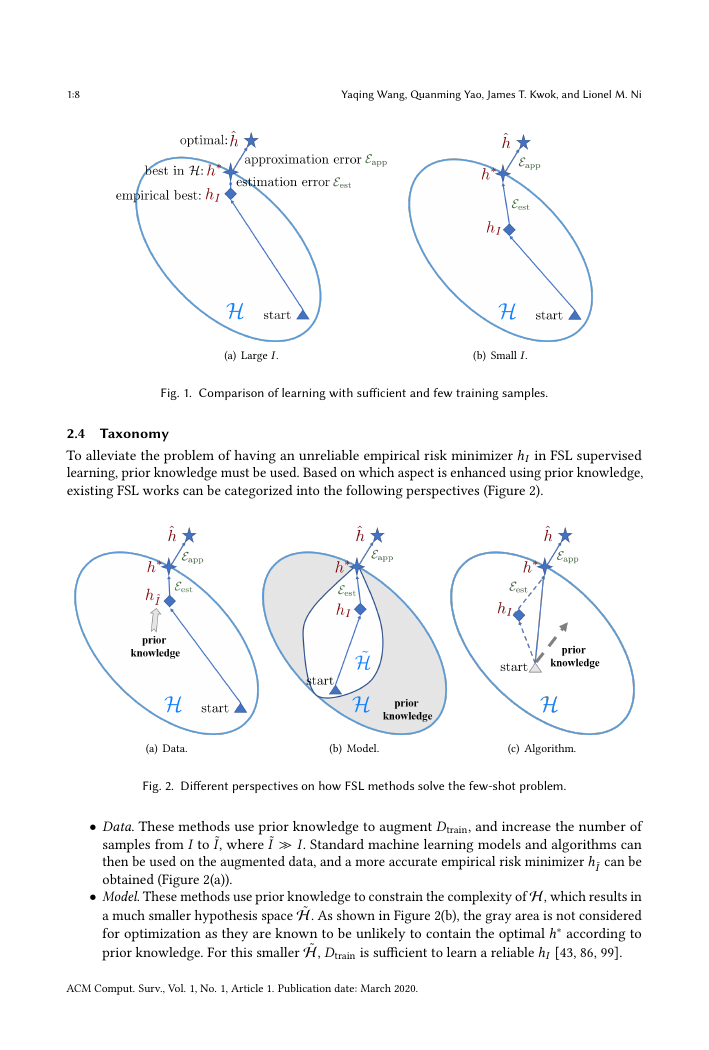

To alleviate the problem of having an unreliable empirical risk minimizer hI in FSL supervised

learning, prior knowledge must be used. Based on which aspect is enhanced using prior knowledge,

existing FSL works can be categorized into the following perspectives (Figure 2).

(a) Data.

(b) Model.

(c) Algorithm.

Fig. 2. Different perspectives on how FSL methods solve the few-shot problem.

• Data. These methods use prior knowledge to augment Dtrain, and increase the number of

samples from I to ˜I, where ˜I ≫ I. Standard machine learning models and algorithms can

then be used on the augmented data, and a more accurate empirical risk minimizer h ˜I

can be

obtained (Figure 2(a)).

• Model. These methods use prior knowledge to constrain the complexity of H, which results in

a much smaller hypothesis space ˜H. As shown in Figure 2(b), the gray area is not considered

for optimization as they are known to be unlikely to contain the optimal h∗ according to

prior knowledge. For this smaller ˜H, Dtrain is sufficient to learn a reliable hI [43, 86, 99].

ACM Comput. Surv., Vol. 1, No. 1, Article 1. Publication date: March 2020.

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc