�

Exploratory Programming for the Arts and

Humanities

Nick Montfort

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

© 2016 Nick Montfort

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means

(including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the

publisher.

This book was set in Stone Sans and Stone Serif by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the

United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Montfort, Nick, author.

Exploratory programming for the arts and humanities / Montfort, Nick.

Cambridge, MA : The MIT Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

LCCN 2015038397 | ISBN 9780262034203 (hardcover : alk. paper)

eISBN 9780262331968

LCSH: Computer programming. | Humanities—Data processing.

LCC QA76.6 .M664 2016 | DDC 005.1—dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015038397

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Although this book does not cover 3D graphics, the cover image both evokes exploration and resulted from

programming in an exploratory, artist-driven mode. The image, used with permission, is a screenshot from Stavros

Papadopoulos’s demo for Project Windstorm, which he developed as he started learning JavaScript and WebGL and

which is available at http://zephyrosanemos.com/.

�

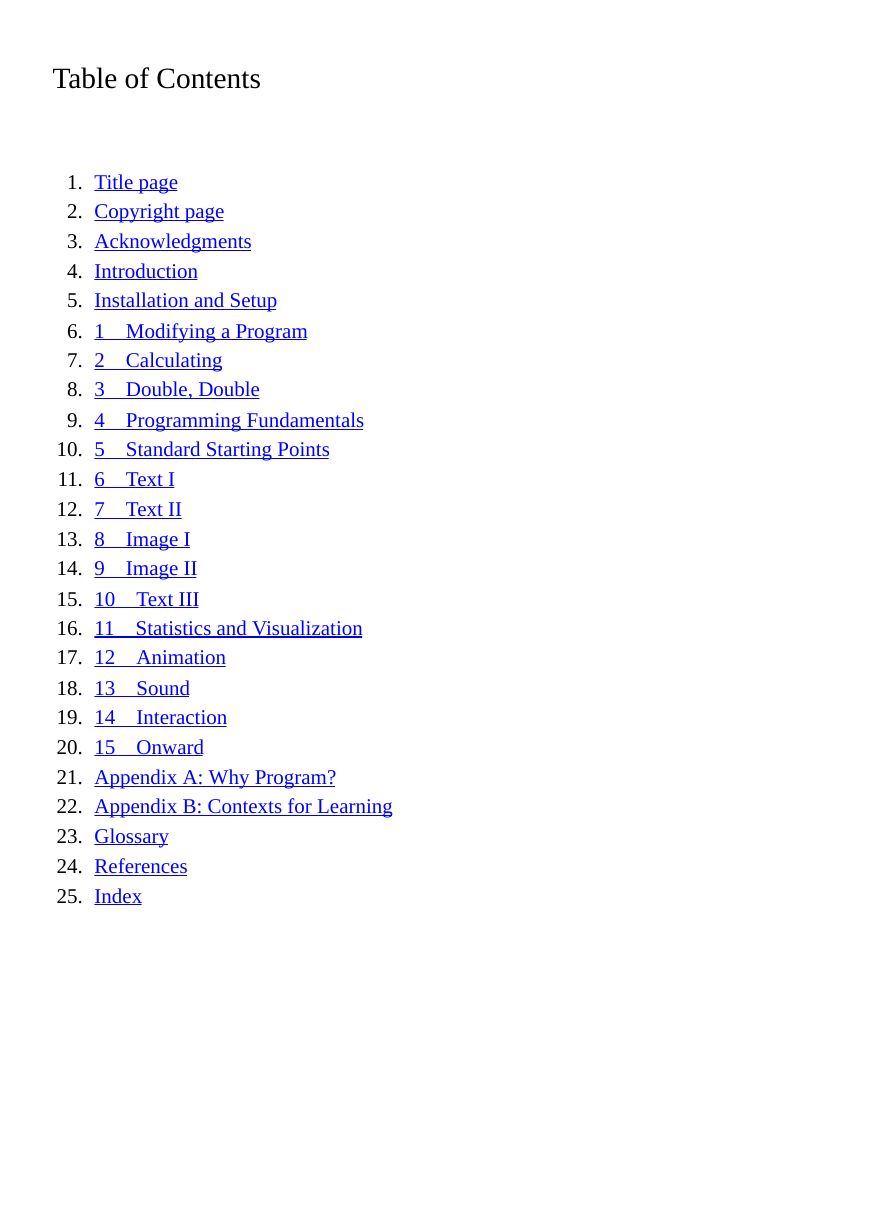

Table of Contents

1. Title page

2. Copyright page

3. Acknowledgments

4. Introduction

5. Installation and Setup

6. 1 Modifying a Program

7. 2 Calculating

8. 3 Double, Double

9. 4 Programming Fundamentals

10. 5 Standard Starting Points

11. 6 Text I

12. 7 Text II

13. 8 Image I

14. 9 Image II

15. 10 Text III

16. 11 Statistics and Visualization

17. 12 Animation

18. 13 Sound

19. 14 Interaction

20. 15 Onward

21. Appendix A: Why Program?

22. Appendix B: Contexts for Learning

23. Glossary

24. References

25. Index

�

Acknowledgments

First, my thanks go to everyone who has taught and encouraged exploratory programming,

from at least the 1960s through today.

Many people discussed the concept of this book with me at different stages of the

project. Some of these informal conversations were quite important to the final direction I

took with the text, for instance, because I learned than many senior artists and researchers

were interested in learning programming using a book of this sort. In response, I

developed a book that could be used in a class or by independent learners.

the opportunity

to

in

the Boston area (at MIT). I also had

I greatly appreciate the opportunity to do daylong and multiday workshops on

exploratory programming in New York (at NYU), in Mexico City (at UAM-Cuajimalpa),

and

teach an

undergraduate/graduate course based directly on a late draft of the book in New York, at

the New School, thanks to Anne Balsamo. My New School students were a great help to

me as I worked to complete this book. I’ve benefited from many experiences teaching

programming, and I also wish to thank my students in semester-long courses at MIT, the

University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Baltimore. At the University of

Pennsylvania, I’m grateful that I learned at least the basics about statistical research in

computer science from Michael Kearns and also learned about natural language

processing from Mitch Marcus and the researchers at the Institute for Research in

Cognitive Science.

My thanks go to several who reviewed the full text of this book. Erik Stayton went

through the full manuscript, commenting on it and correcting it, and also completed all the

exercises. Patsy Baudoin provided detailed comments on a full draft of the manuscript.

My inestimable spouse, Flourish Klink, also did, and supported me in many other ways as

I worked on this project.

My thanks also go to those at the New York gallery Babycastles, where a good bit of

work on this book was done, and particularly to those who helped out there by reading and

commenting on parts of the manuscript as I completed it: Del, Emi, Frank, Justin, Lauren,

Lee, Nitzan, Patrick, Stephanie, and Todd. As I was in the last stages of work on this book,

I got to teach a two-day course based on some of it for the School for Poetic Computation

in New York City, and I thank my students and those who ran the school’s summer session

for this opportunity. I owe some important specifics in this book to conversations with

Benjamin Mako Hill, Warren Sack, and Allison Parrish.

The MIT Press of course arranged for anonymous reviewers to consider both the

proposal and the manuscript closely; I am grateful to these reviewers for their support of

the project and for their valuable comments and suggestions. At the Press, I also

particularly would like to thank Doug Sery, who has discussed, worked on, and supported

my book projects for about a decade and a half now. I can’t imagine having explored as

many issues in digital media and creative computing, in the same breath and depth,

without his backing over the years. I also appreciate the work MIT Press editor Kathy

Caruso (who has worked on three previous books of mine) did to improve the manuscript

and ready the book for publication. Any errors in the published text, after all of these

contributions and work from others, are of course my responsibility.

欢迎加入非盈利Python编程学习交流QQ群783462347,群里免费提供500+本Python书籍!�

The text of appendix A, along with a few paragraphs from the introduction, is also

being published in only slightly different form in A New Companion to Digital

Humanities, edited by Susan Schreibman, Ray Siemens, and John Unsworth (Hoboken,

NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2016), as “Exploratory Programming in Digital Humanities

Pedagogy and Research.”

欢迎加入非盈利Python编程学习交流QQ群783462347,群里免费提供500+本Python书籍!�

Introduction

This is a book about how to think with computation and how to understand computation as

part of culture. Programming is introduced as a way to iteratively design both artworks

and humanities projects, in a process that enables the programmer to discover, in the

process of programming, the ultimate direction that the project will take. My aim is to

explain enough about programming to allow a new programmer to explore and inquire

with computation, and to help such a person go on to learn more about programming

while pursuing projects in the arts and humanities.

I developed this book, in part, for use in college and university courses, as a textbook. I

was glad to have the opportunity to use a draft version of it in an graduate/undergraduate

course in New York City at the New School. I also worked to develop a book that will be

useful to learners, working either individually or alone, who are not taking formal courses.

I provide suggestions for teaching this book, and for learning from it in a class, in

“Appendix B: Contexts for Learning,” which also includes some suggestions for those

pursuing programming less formally.

To some, programming is associated with expertise, professional status, and esoteric

technical difficulty. I don’t think programming needs to be intimidating, any more than the

terms writing or sketching do. These are simply the conventional words for different

activities—creative activities that are also methods for inquiry.

You don’t need any background in programming to learn from this book, and courses

based on this book do not need to require any background. If you are already comfortable

programming, you may still benefit from reading Exploratory Programming for the Arts

and Humanities, particularly if your work as a programmer has been instrumental and you

have mainly worked to implement specifications and solve specific problems. I assume,

though, that a reader has no previous programming experience.

In my approach to programming, I seek to show its exploratory potential—its facility

for sketching, brainstorming, and inquiring about important topics. My discussions,

exercises, and explanations of how programming works also include some significant

consideration of how computation and programming are culturally situated. This means

how programming relates to the manipulation of media of different sorts and, more

broadly, to the methods and questions of the arts and humanities.

This book was written and designed to be read alongside a computer, allowing the

reader to program while progressing through the book. The book is really meant to be part

of a human-book-computer system, one that is set up to help the human learn. After

reading this introductory material, I consider it essential to use this book while

programming.

I ask at times that readers follow along and simply type code in directly from the book,

in part to gain familiarity and comfort with practical aspects of inputting and running

programs. At other times, readers are asked to try out some modifications (some of them

small-scale, some more significant) of existing programs. Some carefully chosen

exercises, initially on a small scale and then more substantial, are provided. In some of

these cases, a specification is given for a program, describing how it is to work in a

欢迎加入非盈利Python编程学习交流QQ群783462347,群里免费提供500+本Python书籍!�

particular way. Although doing such exercises is not an exploratory way to program, they

are included to provide a wider range of programming experiences and foster familiarity

with code and computing. Particularly when learning the fundamentals of programming,

such exercises are important. For these reasons, these exercises are concentrated in the

middle of the book, in chapters 5 and 6.

Finally, throughout the book “free projects” are described. These are intentionally

underspecified exercises, leaving room for readers to determine their own directions and

to write different sorts of programs. In these projects, the final program is to be arrived at

not simply by implementing a fixed specification, but by undertaking some amount of

exploration through programming.

In some books and courses on programming, readers learn about different sorting

algorithms and about how these algorithms have different complexities in space and in

time. These are fine topics, and necessary when building a deep foundation for those who

will go on to understand the science of computation very thoroughly. If you know already

that you are seeking understanding and skills equivalent to a bachelor’s degree in

computer science, or that you actually wish to pursue such a degree, you should probably

find a more appropriate book or take a course that covers that material. Furthermore, if

your interest is only in learning how to program, and not in the use of programming for

exploration or in making a connection between computation and culture, there are good

shorter books worth considering, such as Chris Pine’s Learn to Program, second edition,

which uses Ruby to teach general programming principles. Similarly, if you really don’t

wish to learn to program, but you are interested in how computation relates to issues in the

arts and humanities, there are plenty of books and articles focused on these relationships.

One of them is a book I wrote with nine coauthors, 10 PRINT CHR$(205.5+RND(1)); :

GOTO 10, which studies a one-line BASIC program in great depth, considering many of

its cultural contexts.

It’s fair at this point to be clear about what Exploratory Programming for the Arts and

Humanities is not: It is not an attempt to have readers completely understand any one

particular programming language. It is not meant to show people how to professionally

produce products or complete the typical “deliverables” of software engineering. It is, as

stated earlier, not meant to provide a complete first course for those who will continue to

do significant study of computation itself. This book is certainly compatible with

computer science education, but it is an attempt to lay a different foundation, one for

artistic and humanistic inquiry with computing.

This is a book about how to think with computation—specifically, how to think about

questions in the arts and humanities, and how to do so by means of programming. I

believe this book will supply a solid enough foundation for new programmers that those

who read it, and who follow along and do the exercises, will be able to pursue a greater

ability in specific programming languages, learn about essential matters of collaborating

on software projects, and understand that computation significantly engages with culture

and with intellectual concerns in the arts and humanities. I also hope that working through

this book will reveal the potential of programming as a means of inquiry and art-making—

at least, that it will reveal enough of that potential. As long as it does, readers will likely

be eager to continue their programming, and their inquiry, after they are done with the

欢迎加入非盈利Python编程学习交流QQ群783462347,群里免费提供500+本Python书籍!�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc