An Introduction to Cryptography

Mohamed Barakat, Christian Eder, Timo Hanke

September 20, 2018

�

�

Preface

Second Edition

Lecture notes of a class given during the summer term 2017 at the University of Kaiserslautern. The

notes are based on lecture notes by Mohamed Barakat and Timo Hanke [BH12] (see also below).

Other good sources and books are, for example, [Buc04, Sch95, MVO96].

Many thanks to Raul Epure for proofreading and suggestions to improve the lecture notes.

First Edition

These lecture notes are based on the course “Kryptographie” given by Timo Hanke at RWTH Aachen

University in the summer semester of 2010. They were amended and extended by several topics,

as well as translated into English, by Mohamed Barakat for his course “Cryptography” at TU Kaiser-

slautern in the winter semester of 2010/11. Besides the literature given in the bibliography section,

our sources include lectures notes of courses held by Michael Cuntz, Florian Heß, Gerhard Hiß and

Jürgen Müller. We would like to thank them all.

Mohamed Barakat would also like to thank the audience of the course for their helpful remarks

and questions. Special thanks to Henning Kopp for his numerous improvements suggestions. Also

thanks to Jochen Kall who helped locating further errors and typos. Daniel Berger helped me with

subtle formatting issues. Many thanks Daniel.

i

�

Contents

Second Edition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

First Edition . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Contents

1 Introduction

2 Basic Concepts

2.1 Quick & Dirty Introduction to Complexity Theory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.2 Underlying Structures . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.3 Investigating Security Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3 Modes of Ciphers

3.1 Block Ciphers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.2 Modes of Block Ciphers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.3 Stream Ciphers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.4 A Short Review of Historical Ciphers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4 Information Theory

4.1 A Short Introduction to Probability Theory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.2 Perfect Secrecy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

4.3 Entropy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5 Pseudorandom Sequences

5.1 Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5.2 Linear recurrence equations and pseudorandom bit generators . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5.3 Finite fields . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

5.4 Statistical tests

5.5 Cryptographically secure pseudorandom bit generators

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6 Modern Symmetric Block Ciphers

6.1 Feistel cipher . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.2 Data Encryption Standard (DES) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

6.3 Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7 Candidates of One-Way Functions

7.1 Complexity classes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7.2 Squaring modulo n . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

ii

i

i

ii

1

5

5

7

11

13

13

14

23

25

27

27

31

35

47

47

48

53

62

66

70

70

71

74

77

77

78

�

CONTENTS

7.3 Quadratic residues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7.4 Square roots . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7.5 One-way functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7.6 Trapdoors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7.7 The Blum-Goldwasser construction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8 Public Key Cryptosystems

8.1 RSA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8.2 ElGamal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8.3 The Rabin cryptosystem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8.4 Security models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

iii

79

81

83

84

85

86

86

90

91

93

9 Primality tests

95

9.1 Probabilistic primality tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

95

9.2 Deterministic primality tests . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100

10 Integer Factorization

10.1 Pollard’s p 1 method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 103

10.2 Pollard’s method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104

10.3 Fermat’s method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

10.4 Dixon’s method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 105

10.5 The quadratic sieve . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 107

103

11 Elliptic curves

109

11.1 The projective space . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 109

11.2 The group structure (E, +) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114

11.3 Elliptic curves over finite fields . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 120

11.4 Lenstra’s factorization method . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124

11.5 Elliptic curves cryptography (ECC) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126

12 Attacks on the discrete logarithm problem

128

12.1 Specific attacks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 128

12.2 General attacks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 130

13 Digital signatures

132

13.1 Basic Definitions & Notations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 132

13.2 Signatures using OWF with trapdoors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 133

13.3 Hash functions

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 134

13.4 Signatures using OWF without trapdoors . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 135

A Some analysis

137

A.1 Real functions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137

Bibliography

138

�

�

Chapter 1

Introduction

Cryptology consists of two branches:

Cryptography is the area of constructing cryptographic systems.

Cryptanalysis is the area of breaking cryptographic systems.

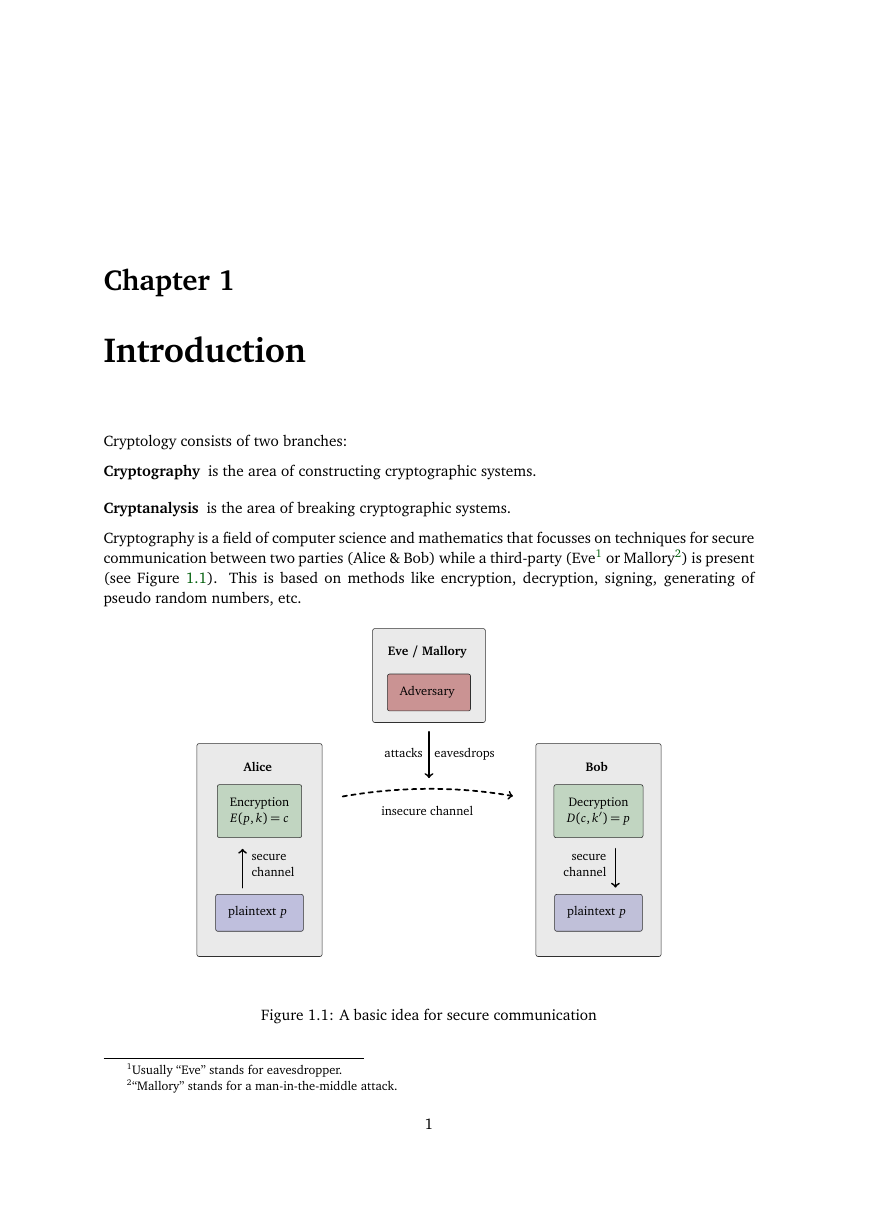

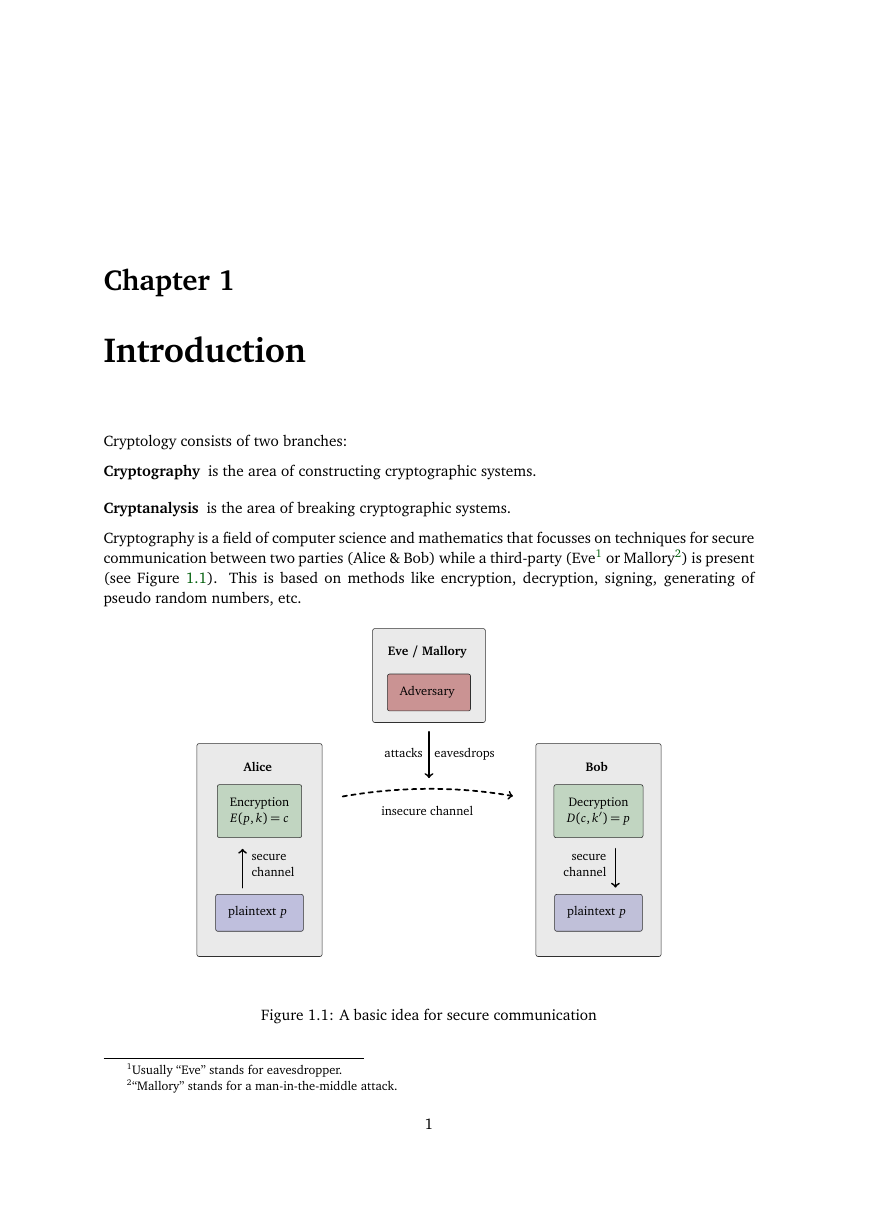

Cryptography is a field of computer science and mathematics that focusses on techniques for secure

communication between two parties (Alice & Bob) while a third-party (Eve1 or Mallory2) is present

(see Figure 1.1). This is based on methods like encryption, decryption, signing, generating of

pseudo random numbers, etc.

Eve / Mallory

Adversary

attacks eavesdrops

insecure channel

Bob

Decryption

′) = p

D(c, k

secure

channel

plaintext p

Alice

Encryption

E(p, k) = c

secure

channel

plaintext p

Figure 1.1: A basic idea for secure communication

1Usually “Eve” stands for eavesdropper.

2“Mallory” stands for a man-in-the-middle attack.

1

�

2

CHAPTER1. INTRODUCTION

The four ground principles of cryptography are

Confidentiality Defines a set of rules that limits access or adds restriction on certain information.

Data Integrity Takes care of the consistency and accuracy of data during its entire life-cycle.

Authentication Confirms the truth of an attribute of a datum that is claimed to be true by some

entity.

Non-Repudiation Ensures the inability of an author of a statement resp. a piece of information to

deny it.

Nowadays there are in general two different schemes: On the one hand, there are symmetric

schemes, where both, Alice and Bob, need to have the same key in order to encrypt their com-

munication. For this, they have to securely exchange the key initially. On the other hand, since

Diffie and Hellman’s key exchange idea from 1976 (see also Example 1.1 (3) and Chapter 8) there

also exists the concept of asymmetric schemes where Alice and Bob both have a private and a public

key. The public key can be shared with anyone, so Bob can use it to encrypt a message for Alice.

But only Alice, with the corresponding private key, can decrypt the encrypted message from Bob.

In this lecture we will discover several well-known cryptographic structures like RSA (Rivest-

Shamir-Adleman cryptosystem), DES (Data Encryption Standard), AES (Advanced Encryption

Standard), ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography), and many more. All these structures have two

main aspects:

1. There is the security of the structure itself, based on mathematics. There is a standardiza-

tion process for cryptosystems based on theoretical research in mathematics and complexity

theory. Here our focus will lay in this lecture.

2. Then we have the implementation of the structures in devices, e.g. SSL, TLS in your web

browser or GPG for signed resp. encrypted emails. These implementations should not di-

verge from the theoretical standards, but must still be very fast and convenient for the user.

It is often this mismatch between these requirements that leads to practical attacks of theoretically

secure systems, e.g. [Wik16b, Wik16c, Wik16e].

Before we start defining the basic notation let us motivate the following with some historically

known cryptosystems:

Example 1.1.

1. One of the most famous cryptosystems goes back to Julius Ceasar: Caesar’s cipher does the

following: Take the latin alphabet and apply a mapping A7! 0, B 7! 1, . . . , Z 7! 25. Now we

apply a shifting map

x 7! (x + k) mod 26

for some secret k 2 Z. For example, ATTACK maps to CVVCEM for k = 2. This describes the

encryption process. The decryption is applied via the map

y 7! ( y k) mod 26

with the same k. Clearly, both parties need to know k in advance. Problems with this cipher:

Same letters are mapped to the same shifted letters, each language has its typical distribu-

tion of letters, e.g. E is used much more frequently in the English language than K. Besides

investigating only single letters one can also check for letter combinations of length 2-3, etc.

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc