To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

Our gain in net worth during 1994 was $1.45 billion or 13.9%.

Over the last 30 years (that is, since present management took

over) our per-share book value has grown from $19 to $10,083, or

at a rate of 23% compounded annually.

Charlie Munger, Berkshire's Vice Chairman and my partner,

and I make few predictions. One we will confidently offer,

however, is that the future performance of Berkshire won't come

close to matching the performance of the past.

The problem is not that what has worked in the past will

cease to work in the future. To the contrary, we believe that

our formula - the purchase at sensible prices of businesses that

have good underlying economics and are run by honest and able

people - is certain to produce reasonable success. We expect,

therefore, to keep on doing well.

A fat wallet, however, is the enemy of superior investment

results. And Berkshire now has a net worth of $11.9 billion

compared to about $22 million when Charlie and I began to manage

the company. Though there are as many good businesses as ever,

it is useless for us to make purchases that are inconsequential

in relation to Berkshire's capital. (As Charlie regularly

reminds me, "If something is not worth doing at all, it's not

worth doing well.") We now consider a security for purchase only

if we believe we can deploy at least $100 million in it. Given

that minimum, Berkshire's investment universe has shrunk

dramatically.

Nevertheless, we will stick with the approach that got us

here and try not to relax our standards. Ted Williams, in

The Story of My Life, explains why: "My argument is, to be

a good hitter, you've got to get a good ball to hit. It's the

first rule in the book. If I have to bite at stuff that is out

of my happy zone, I'm not a .344 hitter. I might only be a .250

hitter." Charlie and I agree and will try to wait for

opportunities that are well within our own "happy zone."

We will continue to ignore political and economic forecasts,

which are an expensive distraction for many investors and

businessmen. Thirty years ago, no one could have foreseen the

huge expansion of the Vietnam War, wage and price controls, two

oil shocks, the resignation of a president, the dissolution of

the Soviet Union, a one-day drop in the Dow of 508 points, or

treasury bill yields fluctuating between 2.8% and 17.4%.

But, surprise - none of these blockbuster events made the

slightest dent in Ben Graham's investment principles. Nor did

they render unsound the negotiated purchases of fine businesses

at sensible prices. Imagine the cost to us, then, if we had let

a fear of unknowns cause us to defer or alter the deployment of

capital. Indeed, we have usually made our best purchases when

apprehensions about some macro event were at a peak. Fear is the

foe of the faddist, but the friend of the fundamentalist.

A different set of major shocks is sure to occur in the next

30 years. We will neither try to predict these nor to profit

from them. If we can identify businesses similar to those we

have purchased in the past, external surprises will have little

effect on our long-term results.

B

E

R

K

S

H

I

R

E

H

A

T

H

A

W

A

Y

I

N

C

.

�

What we promise you - along with more modest gains - is that

during your ownership of Berkshire, you will fare just as Charlie

and I do. If you suffer, we will suffer; if we prosper, so will

you. And we will not break this bond by introducing compensation

arrangements that give us a greater participation in the upside

than the downside.

We further promise you that our personal fortunes will

remain overwhelmingly concentrated in Berkshire shares: We will

not ask you to invest with us and then put our own money

elsewhere. In addition, Berkshire dominates both the investment

portfolios of most members of our families and of a great many

friends who belonged to partnerships that Charlie and I ran in

the 1960's. We could not be more motivated to do our best.

Luckily, we have a good base from which to work. Ten years

ago, in 1984, Berkshire's insurance companies held securities

having a value of $1.7 billion, or about $1,500 per Berkshire

share. Leaving aside all income and capital gains from those

securities, Berkshire's pre-tax earnings that year were only

about $6 million. We had earnings, yes, from our various

manufacturing, retailing and service businesses, but they were

almost entirely offset by the combination of underwriting losses

in our insurance business, corporate overhead and interest

expense.

Now we hold securities worth $18 billion, or over $15,000

per Berkshire share. If you again exclude all income from these

securities, our pre-tax earnings in 1994 were about $384 million.

During the decade, employment has grown from 5,000 to 22,000

(including eleven people at World Headquarters).

We achieved our gains through the efforts of a superb corps

of operating managers who get extraordinary results from some

ordinary-appearing businesses. Casey Stengel described managing

a baseball team as "getting paid for home runs other fellows

hit." That's my formula at Berkshire, also.

The businesses in which we have partial interests are

equally important to Berkshire's success. A few statistics will

illustrate their significance: In 1994, Coca-Cola sold about 280

billion 8-ounce servings and earned a little less than a penny on

each. But pennies add up. Through Berkshire's 7.8% ownership of

Coke, we have an economic interest in 21 billion of its servings,

which produce "soft-drink earnings" for us of nearly $200

million. Similarly, by way of its Gillette stock, Berkshire has

a 7% share of the world's razor and blade market (measured by

revenues, not by units), a proportion according us about $250

million of sales in 1994. And, at Wells Fargo, a $53 billion

bank, our 13% ownership translates into a $7 billion "Berkshire

Bank" that earned about $100 million during 1994.

It's far better to own a significant portion of the Hope

diamond than 100% of a rhinestone, and the companies just

mentioned easily qualify as rare gems. Best of all, we aren't

limited to simply a few of this breed, but instead possess a

growing collection.

Stock prices will continue to fluctuate - sometimes sharply

- and the economy will have its ups and down. Over time,

however, we believe it highly probable that the sort of

businesses we own will continue to increase in value at a

satisfactory rate.

Book Value and Intrinsic Value

We regularly report our per-share book value, an easily

calculable number, though one of limited use. Just as regularly,

�

we tell you that what counts is intrinsic value, a number that is

impossible to pinpoint but essential to estimate.

For example, in 1964, we could state with certitude that

Berkshire's per-share book value was $19.46. However, that

figure considerably overstated the stock's intrinsic value since

all of the company's resources were tied up in a sub-profitable

textile business. Our textile assets had neither going-concern

nor liquidation values equal to their carrying values. In 1964,

then, anyone inquiring into the soundness of Berkshire's balance

sheet might well have deserved the answer once offered up by a

Hollywood mogul of dubious reputation: "Don't worry, the

liabilities are solid."

Today, Berkshire's situation has reversed: Many of the

businesses we control are worth far more than their carrying

value. (Those we don't control, such as Coca-Cola or Gillette,

are carried at current market values.) We continue to give you

book value figures, however, because they serve as a rough,

albeit significantly understated, tracking measure for Berkshire's

intrinsic value. Last year, in fact, the two measures moved in

concert: Book value gained 13.9%, and that was the approximate

gain in intrinsic value also.

We define intrinsic value as the discounted value of the

cash that can be taken out of a business during its remaining

life. Anyone calculating intrinsic value necessarily comes up

with a highly subjective figure that will change both as

estimates of future cash flows are revised and as interest rates

move. Despite its fuzziness, however, intrinsic value is all-

important and is the only logical way to evaluate the relative

attractiveness of investments and businesses.

To see how historical input (book value) and future output

(intrinsic value) can diverge, let's look at another form of

investment, a college education. Think of the education's cost

as its "book value." If it is to be accurate, the cost should

include the earnings that were foregone by the student because he

chose college rather than a job.

For this exercise, we will ignore the important non-economic

benefits of an education and focus strictly on its economic

value. First, we must estimate the earnings that the graduate

will receive over his lifetime and subtract from that figure an

estimate of what he would have earned had he lacked his

education. That gives us an excess earnings figure, which must

then be discounted, at an appropriate interest rate, back to

graduation day. The dollar result equals the intrinsic economic

value of the education.

Some graduates will find that the book value of their

education exceeds its intrinsic value, which means that whoever

paid for the education didn't get his money's worth. In other

cases, the intrinsic value of an education will far exceed its

book value, a result that proves capital was wisely deployed. In

all cases, what is clear is that book value is meaningless as an

indicator of intrinsic value.

Now let's get less academic and look at Scott Fetzer, an

example from Berkshire's own experience. This account will not

only illustrate how the relationship of book value and intrinsic

value can change but also will provide an accounting lesson that

I know you have been breathlessly awaiting. Naturally, I've

chosen here to talk about an acquisition that has turned out to

be a huge winner.

Berkshire purchased Scott Fetzer at the beginning of 1986.

At the time, the company was a collection of 22 businesses, and

today we have exactly the same line-up - no additions and no

�

disposals. Scott Fetzer's main operations are World Book, Kirby,

and Campbell Hausfeld, but many other units are important

contributors to earnings as well.

We paid $315.2 million for Scott Fetzer, which at the time

had $172.6 million of book value. The $142.6 million premium we

handed over indicated our belief that the company's intrinsic

value was close to double its book value.

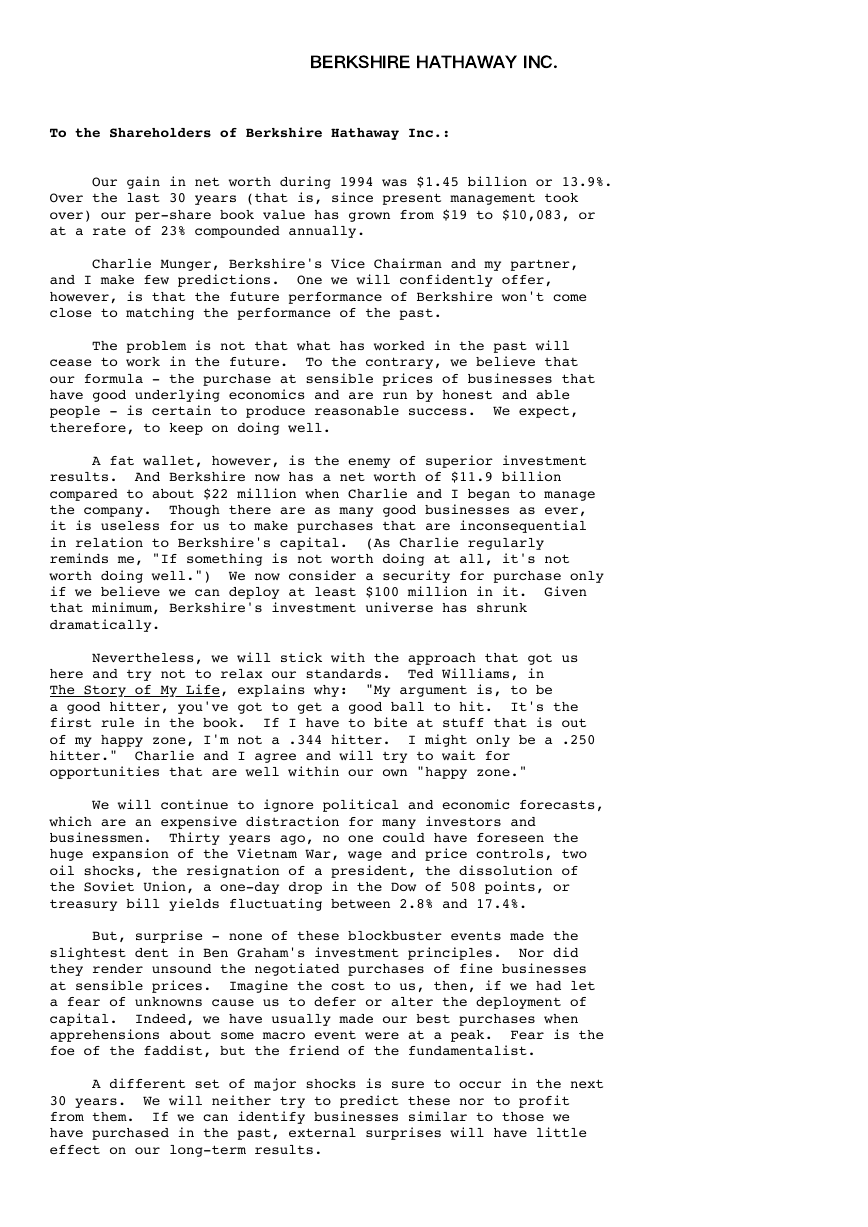

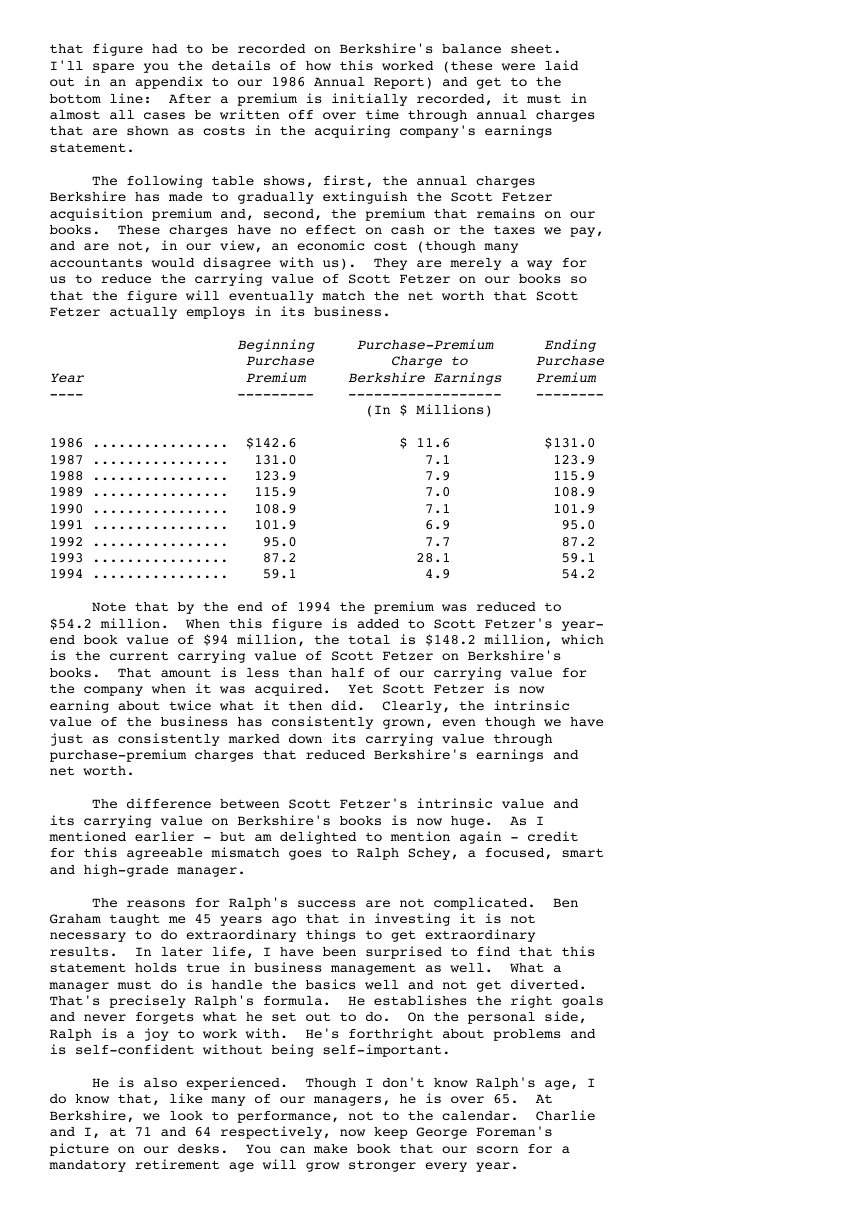

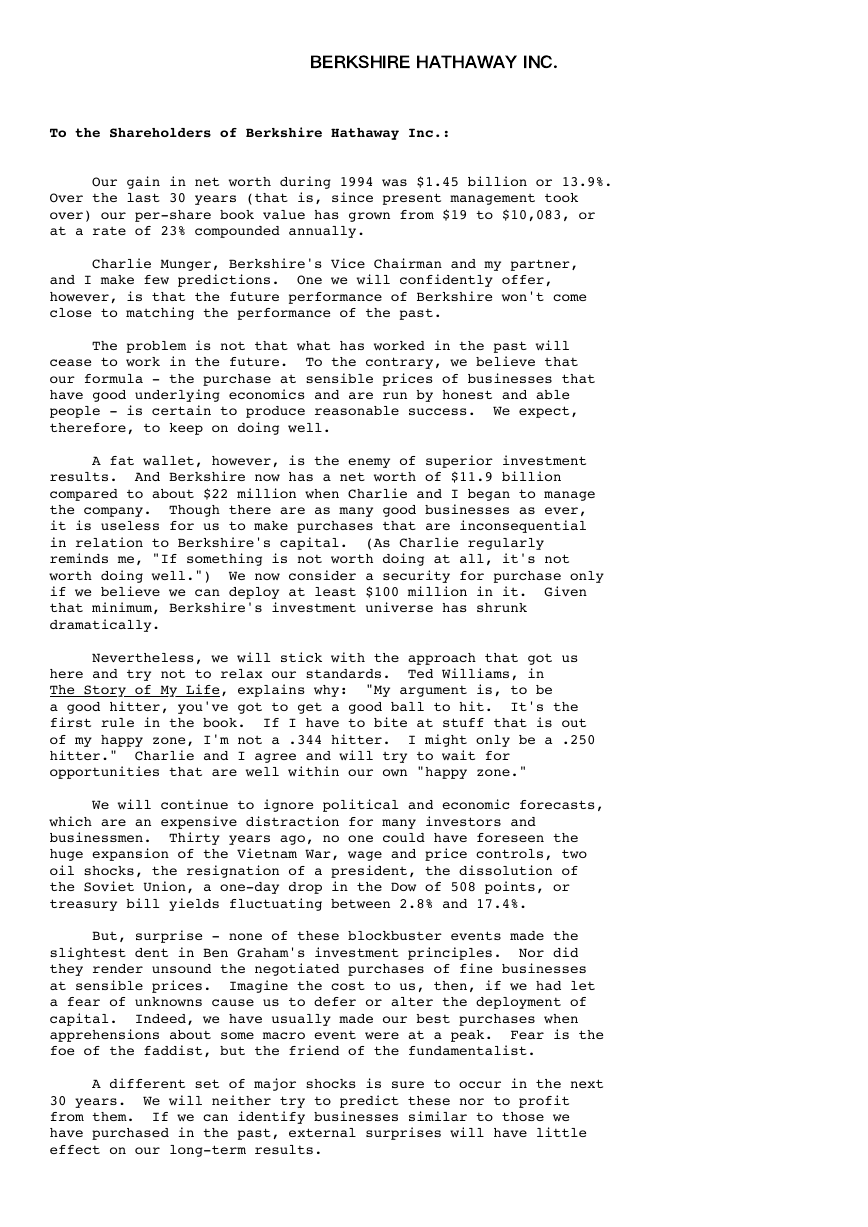

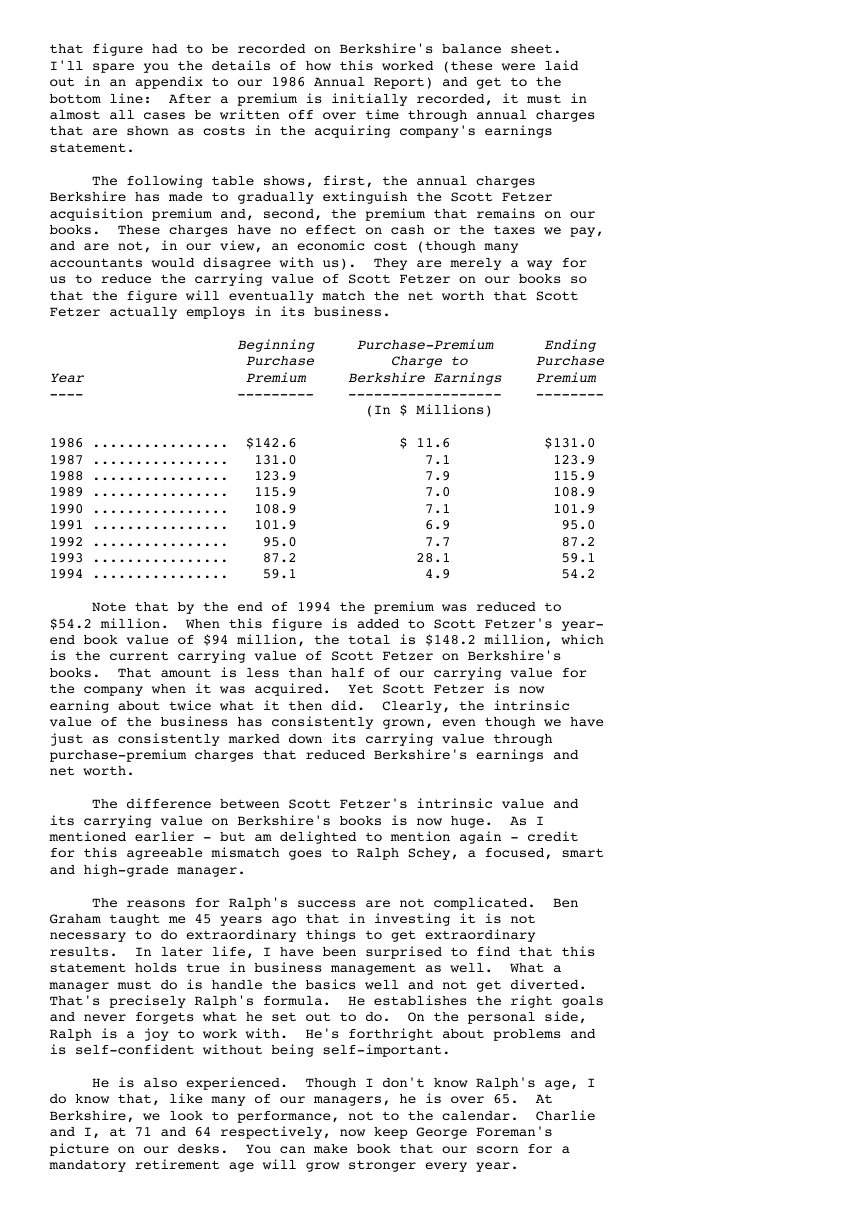

In the table below we trace the book value of Scott Fetzer,

as well as its earnings and dividends, since our purchase.

(1) (4)

Beginning (2) (3) Ending

Year Book Value Earnings Dividends Book Value

---- ---------- -------- --------- ----------

(In $ Millions) (1)+(2)-(3)

1986 ............... $172.6 $ 40.3 $125.0 $ 87.9

1987 ............... 87.9 48.6 41.0 95.5

1988 ............... 95.5 58.0 35.0 118.6

1989 ............... 118.6 58.5 71.5 105.5

1990 ............... 105.5 61.3 33.5 133.3

1991 ............... 133.3 61.4 74.0 120.7

1992 ............... 120.7 70.5 80.0 111.2

1993 ............... 111.2 77.5 98.0 90.7

1994 ............... 90.7 79.3 76.0 94.0

Because it had excess cash when our deal was made, Scott

Fetzer was able to pay Berkshire dividends of $125 million in

1986, though it earned only $40.3 million. I should mention that

we have not introduced leverage into Scott Fetzer's balance

sheet. In fact, the company has gone from very modest debt when

we purchased it to virtually no debt at all (except for debt used

by its finance subsidiary). Similarly, we have not sold plants

and leased them back, nor sold receivables, nor the like.

Throughout our years of ownership, Scott Fetzer has operated as a

conservatively-financed and liquid enterprise.

As you can see, Scott Fetzer's earnings have increased

steadily since we bought it, but book value has not grown

commensurately. Consequently, return on equity, which was

exceptional at the time of our purchase, has now become truly

extraordinary. Just how extraordinary is illustrated by

comparing Scott Fetzer's performance to that of the Fortune 500,

a group it would qualify for if it were a stand-alone company.

Had Scott Fetzer been on the 1993 500 list - the latest

available for inspection - the company's return on equity would

have ranked 4th. But that is far from the whole story. The top

three companies in return on equity were Insilco, LTV and Gaylord

Container, each of which emerged from bankruptcy in 1993 and none

of which achieved meaningful earnings that year except for those

they realized when they were accorded debt forgiveness in

bankruptcy proceedings. Leaving aside such non-operating

windfalls, Scott Fetzer's return on equity would have ranked it

first on the Fortune 500, well ahead of number two. Indeed,

Scott Fetzer's return on equity was double that of the company

ranking tenth.

You might expect that Scott Fetzer's success could only be

explained by a cyclical peak in earnings, a monopolistic

position, or leverage. But no such circumstances apply. Rather,

the company's success comes from the managerial expertise of CEO

Ralph Schey, of whom I'll tell you more later.

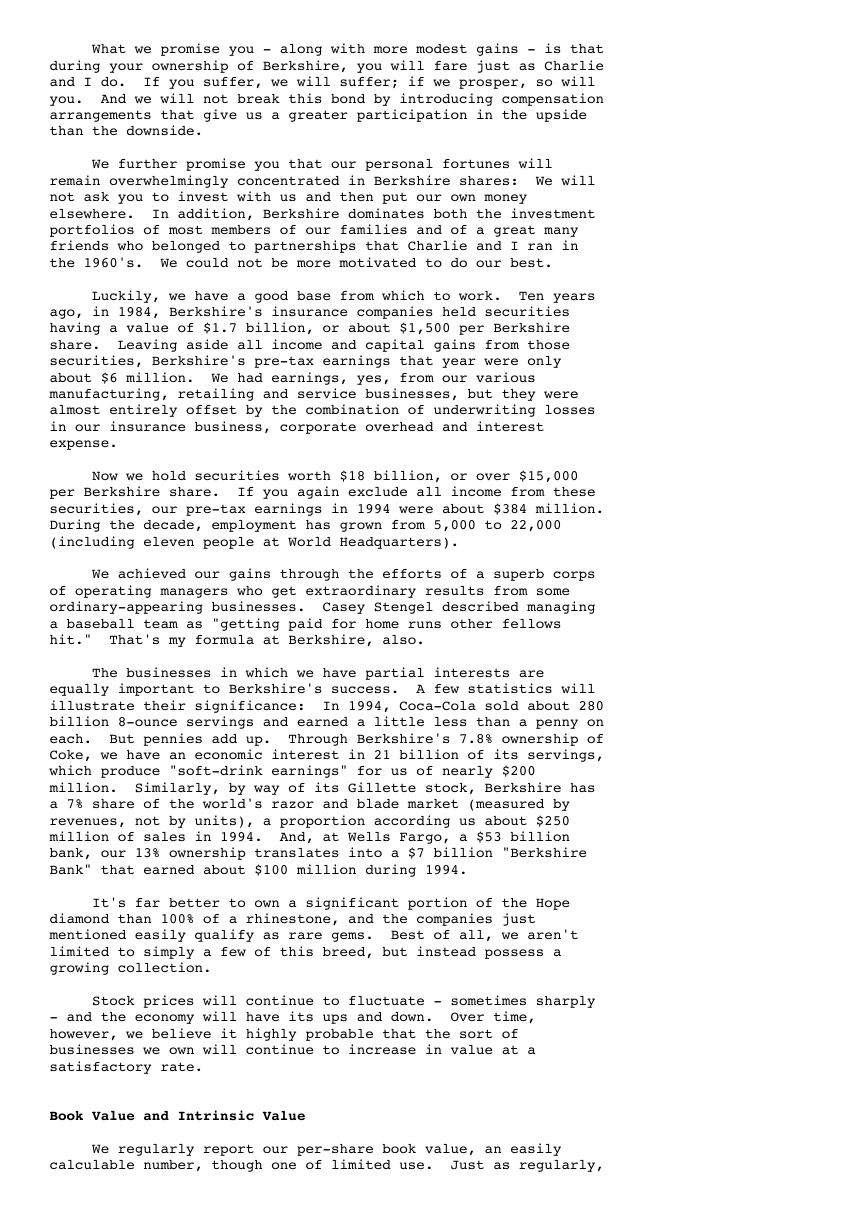

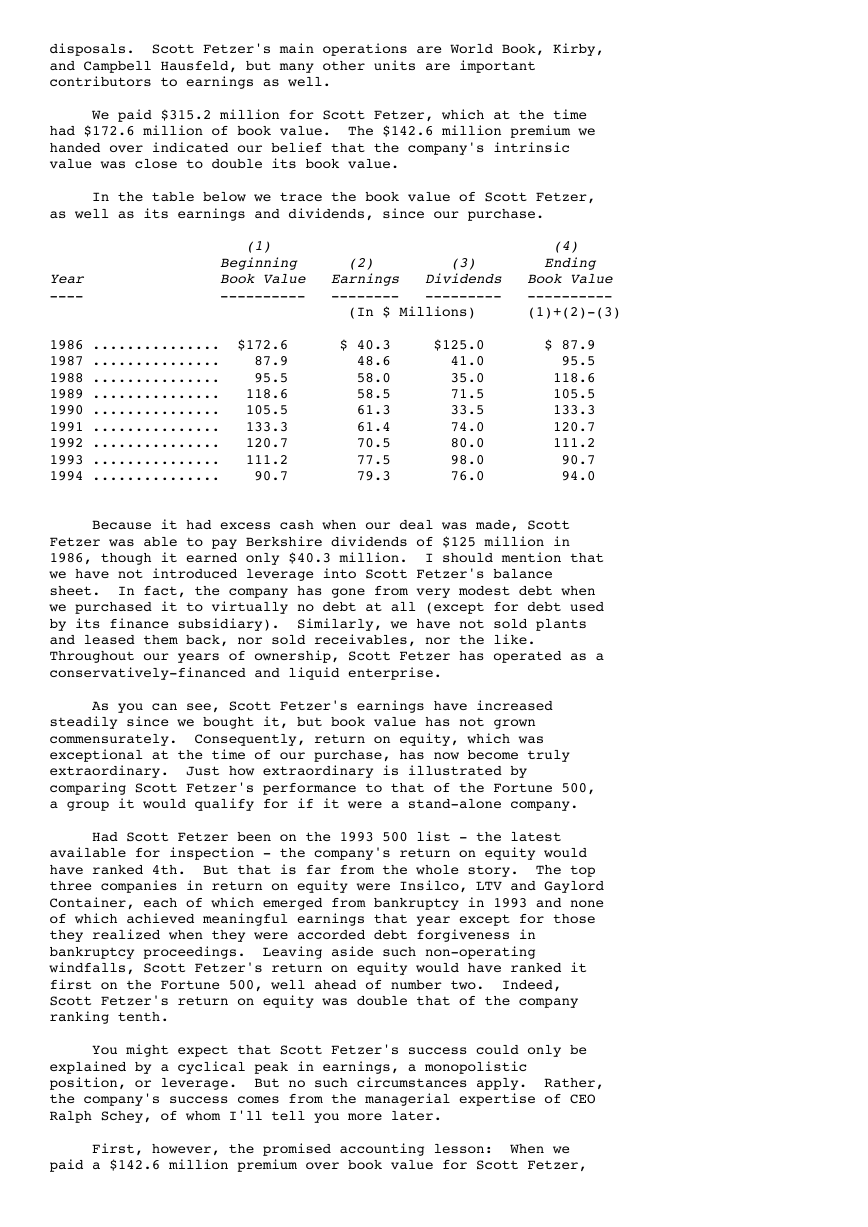

First, however, the promised accounting lesson: When we

paid a $142.6 million premium over book value for Scott Fetzer,

�

that figure had to be recorded on Berkshire's balance sheet.

I'll spare you the details of how this worked (these were laid

out in an appendix to our 1986 Annual Report) and get to the

bottom line: After a premium is initially recorded, it must in

almost all cases be written off over time through annual charges

that are shown as costs in the acquiring company's earnings

statement.

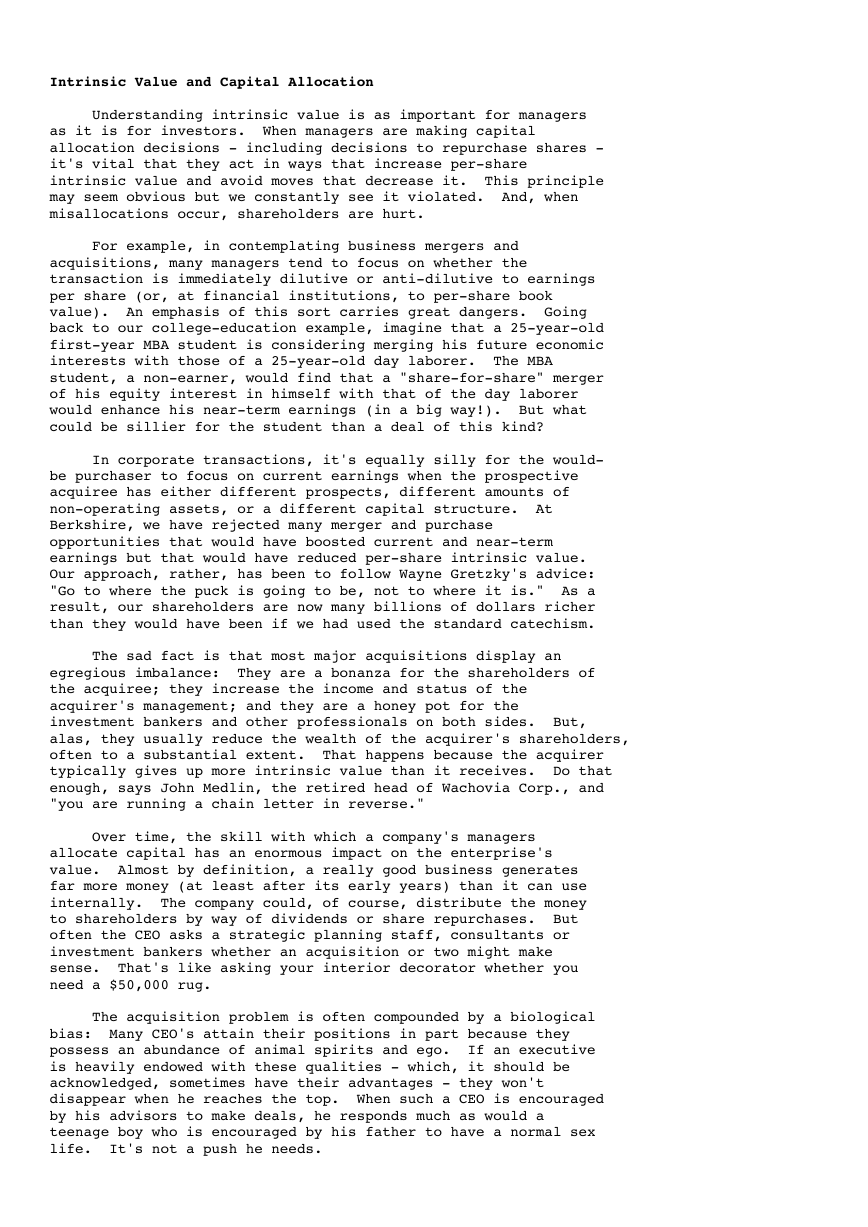

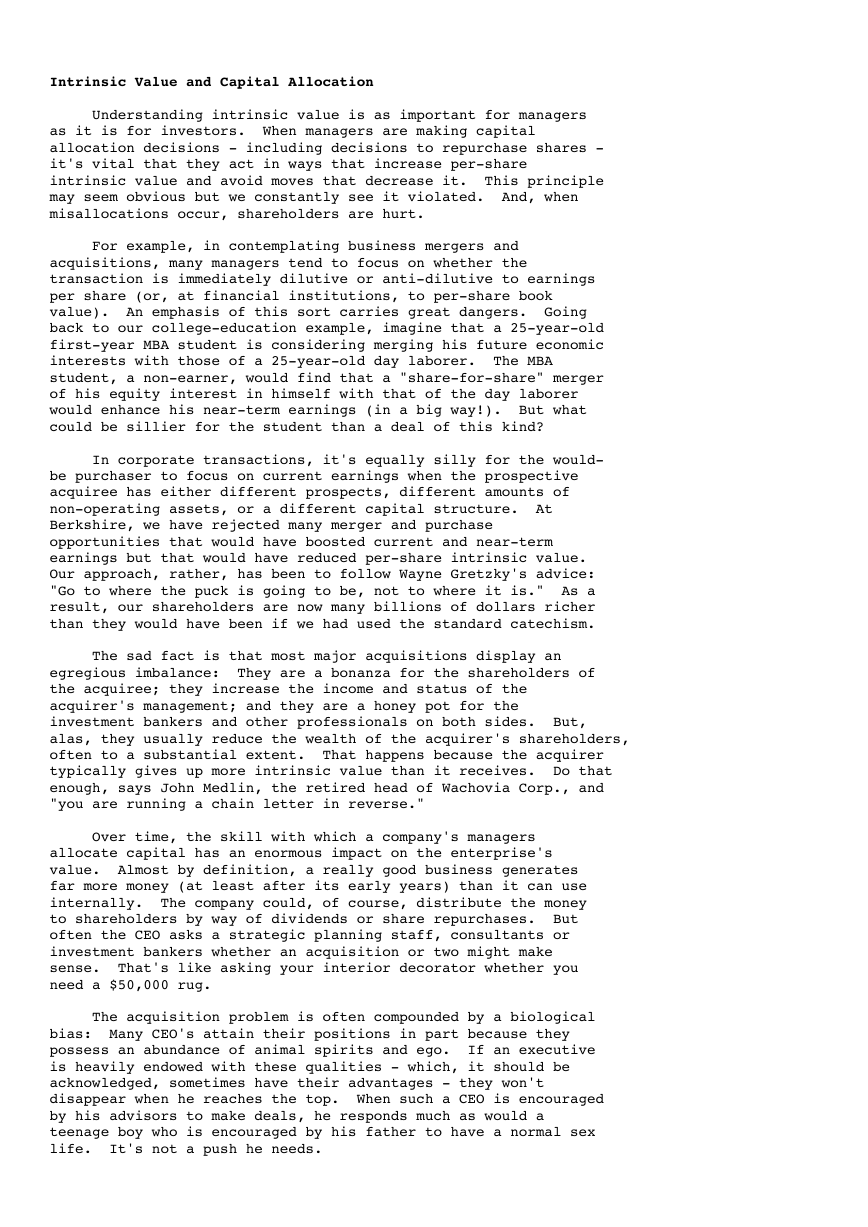

The following table shows, first, the annual charges

Berkshire has made to gradually extinguish the Scott Fetzer

acquisition premium and, second, the premium that remains on our

books. These charges have no effect on cash or the taxes we pay,

and are not, in our view, an economic cost (though many

accountants would disagree with us). They are merely a way for

us to reduce the carrying value of Scott Fetzer on our books so

that the figure will eventually match the net worth that Scott

Fetzer actually employs in its business.

Beginning Purchase-Premium Ending

Purchase Charge to Purchase

Year Premium Berkshire Earnings Premium

---- --------- ------------------ --------

(In $ Millions)

1986 ................ $142.6 $ 11.6 $131.0

1987 ................ 131.0 7.1 123.9

1988 ................ 123.9 7.9 115.9

1989 ................ 115.9 7.0 108.9

1990 ................ 108.9 7.1 101.9

1991 ................ 101.9 6.9 95.0

1992 ................ 95.0 7.7 87.2

1993 ................ 87.2 28.1 59.1

1994 ................ 59.1 4.9 54.2

Note that by the end of 1994 the premium was reduced to

$54.2 million. When this figure is added to Scott Fetzer's year-

end book value of $94 million, the total is $148.2 million, which

is the current carrying value of Scott Fetzer on Berkshire's

books. That amount is less than half of our carrying value for

the company when it was acquired. Yet Scott Fetzer is now

earning about twice what it then did. Clearly, the intrinsic

value of the business has consistently grown, even though we have

just as consistently marked down its carrying value through

purchase-premium charges that reduced Berkshire's earnings and

net worth.

The difference between Scott Fetzer's intrinsic value and

its carrying value on Berkshire's books is now huge. As I

mentioned earlier - but am delighted to mention again - credit

for this agreeable mismatch goes to Ralph Schey, a focused, smart

and high-grade manager.

The reasons for Ralph's success are not complicated. Ben

Graham taught me 45 years ago that in investing it is not

necessary to do extraordinary things to get extraordinary

results. In later life, I have been surprised to find that this

statement holds true in business management as well. What a

manager must do is handle the basics well and not get diverted.

That's precisely Ralph's formula. He establishes the right goals

and never forgets what he set out to do. On the personal side,

Ralph is a joy to work with. He's forthright about problems and

is self-confident without being self-important.

He is also experienced. Though I don't know Ralph's age, I

do know that, like many of our managers, he is over 65. At

Berkshire, we look to performance, not to the calendar. Charlie

and I, at 71 and 64 respectively, now keep George Foreman's

picture on our desks. You can make book that our scorn for a

mandatory retirement age will grow stronger every year.

�

Intrinsic Value and Capital Allocation

Understanding intrinsic value is as important for managers

as it is for investors. When managers are making capital

allocation decisions - including decisions to repurchase shares -

it's vital that they act in ways that increase per-share

intrinsic value and avoid moves that decrease it. This principle

may seem obvious but we constantly see it violated. And, when

misallocations occur, shareholders are hurt.

For example, in contemplating business mergers and

acquisitions, many managers tend to focus on whether the

transaction is immediately dilutive or anti-dilutive to earnings

per share (or, at financial institutions, to per-share book

value). An emphasis of this sort carries great dangers. Going

back to our college-education example, imagine that a 25-year-old

first-year MBA student is considering merging his future economic

interests with those of a 25-year-old day laborer. The MBA

student, a non-earner, would find that a "share-for-share" merger

of his equity interest in himself with that of the day laborer

would enhance his near-term earnings (in a big way!). But what

could be sillier for the student than a deal of this kind?

In corporate transactions, it's equally silly for the would-

be purchaser to focus on current earnings when the prospective

acquiree has either different prospects, different amounts of

non-operating assets, or a different capital structure. At

Berkshire, we have rejected many merger and purchase

opportunities that would have boosted current and near-term

earnings but that would have reduced per-share intrinsic value.

Our approach, rather, has been to follow Wayne Gretzky's advice:

"Go to where the puck is going to be, not to where it is." As a

result, our shareholders are now many billions of dollars richer

than they would have been if we had used the standard catechism.

The sad fact is that most major acquisitions display an

egregious imbalance: They are a bonanza for the shareholders of

the acquiree; they increase the income and status of the

acquirer's management; and they are a honey pot for the

investment bankers and other professionals on both sides. But,

alas, they usually reduce the wealth of the acquirer's shareholders,

often to a substantial extent. That happens because the acquirer

typically gives up more intrinsic value than it receives. Do that

enough, says John Medlin, the retired head of Wachovia Corp., and

"you are running a chain letter in reverse."

Over time, the skill with which a company's managers

allocate capital has an enormous impact on the enterprise's

value. Almost by definition, a really good business generates

far more money (at least after its early years) than it can use

internally. The company could, of course, distribute the money

to shareholders by way of dividends or share repurchases. But

often the CEO asks a strategic planning staff, consultants or

investment bankers whether an acquisition or two might make

sense. That's like asking your interior decorator whether you

need a $50,000 rug.

The acquisition problem is often compounded by a biological

bias: Many CEO's attain their positions in part because they

possess an abundance of animal spirits and ego. If an executive

is heavily endowed with these qualities - which, it should be

acknowledged, sometimes have their advantages - they won't

disappear when he reaches the top. When such a CEO is encouraged

by his advisors to make deals, he responds much as would a

teenage boy who is encouraged by his father to have a normal sex

life. It's not a push he needs.

�

Some years back, a CEO friend of mine - in jest, it must be

said - unintentionally described the pathology of many big deals.

This friend, who ran a property-casualty insurer, was explaining

to his directors why he wanted to acquire a certain life

insurance company. After droning rather unpersuasively through

the economics and strategic rationale for the acquisition, he

abruptly abandoned the script. With an impish look, he simply

said: "Aw, fellas, all the other kids have one."

At Berkshire, our managers will continue to earn

extraordinary returns from what appear to be ordinary businesses.

As a first step, these managers will look for ways to deploy

their earnings advantageously in their businesses. What's left,

they will send to Charlie and me. We then will try to use those

funds in ways that build per-share intrinsic value. Our goal

will be to acquire either part or all of businesses that we

believe we understand, that have good, sustainable underlying

economics, and that are run by managers whom we like, admire and

trust.

Compensation

At Berkshire, we try to be as logical about compensation as

about capital allocation. For example, we compensate Ralph Schey

based upon the results of Scott Fetzer rather than those of

Berkshire. What could make more sense, since he's responsible

for one operation but not the other? A cash bonus or a stock

option tied to the fortunes of Berkshire would provide totally

capricious rewards to Ralph. He could, for example, be hitting

home runs at Scott Fetzer while Charlie and I rang up mistakes at

Berkshire, thereby negating his efforts many times over.

Conversely, why should option profits or bonuses be heaped upon

Ralph if good things are occurring in other parts of Berkshire

but Scott Fetzer is lagging?

In setting compensation, we like to hold out the promise of

large carrots, but make sure their delivery is tied directly to

results in the area that a manager controls. When capital

invested in an operation is significant, we also both charge

managers a high rate for incremental capital they employ and

credit them at an equally high rate for capital they release.

The product of this money's-not-free approach is definitely

visible at Scott Fetzer. If Ralph can employ incremental funds

at good returns, it pays him to do so: His bonus increases when

earnings on additional capital exceed a meaningful hurdle charge.

But our bonus calculation is symmetrical: If incremental

investment yields sub-standard returns, the shortfall is costly

to Ralph as well as to Berkshire. The consequence of this two-

way arrangement is that it pays Ralph - and pays him well - to

send to Omaha any cash he can't advantageously use in his

business.

It has become fashionable at public companies to describe

almost every compensation plan as aligning the interests of

management with those of shareholders. In our book, alignment

means being a partner in both directions, not just on the upside.

Many "alignment" plans flunk this basic test, being artful forms

of "heads I win, tails you lose."

A common form of misalignment occurs in the typical stock

option arrangement, which does not periodically increase the

option price to compensate for the fact that retained earnings

are building up the wealth of the company. Indeed, the

combination of a ten-year option, a low dividend payout, and

compound interest can provide lush gains to a manager who has

done no more than tread water in his job. A cynic might even

note that when payments to owners are held down, the profit to

�

the option-holding manager increases. I have yet to see this

vital point spelled out in a proxy statement asking shareholders

to approve an option plan.

I can't resist mentioning that our compensation arrangement

with Ralph Schey was worked out in about five minutes,

immediately upon our purchase of Scott Fetzer and without the

"help" of lawyers or compensation consultants. This arrangement

embodies a few very simple ideas - not the kind of terms favored

by consultants who cannot easily send a large bill unless they

have established that you have a large problem (and one, of

course, that requires an annual review). Our agreement with

Ralph has never been changed. It made sense to him and to me in

1986, and it makes sense now. Our compensation arrangements with

the managers of all our other units are similarly simple, though

the terms of each agreement vary to fit the economic

characteristics of the business at issue, the existence in some

cases of partial ownership of the unit by managers, etc.

In all instances, we pursue rationality. Arrangements that

pay off in capricious ways, unrelated to a manager's personal

accomplishments, may well be welcomed by certain managers. Who,

after all, refuses a free lottery ticket? But such arrangements

are wasteful to the company and cause the manager to lose focus

on what should be his real areas of concern. Additionally,

irrational behavior at the parent may well encourage imitative

behavior at subsidiaries.

At Berkshire, only Charlie and I have the managerial

responsibility for the entire business. Therefore, we are the

only parties who should logically be compensated on the basis of

what the enterprise does as a whole. Even so, that is not a

compensation arrangement we desire. We have carefully designed

both the company and our jobs so that we do things we enjoy with

people we like. Equally important, we are forced to do very few

boring or unpleasant tasks. We are the beneficiaries as well of

the abundant array of material and psychic perks that flow to the

heads of corporations. Under such idyllic conditions, we don't

expect shareholders to ante up loads of compensation for which we

have no possible need.

Indeed, if we were not paid at all, Charlie and I would be

delighted with the cushy jobs we hold. At bottom, we subscribe

to Ronald Reagan's creed: "It's probably true that hard work

never killed anyone, but I figure why take the chance."

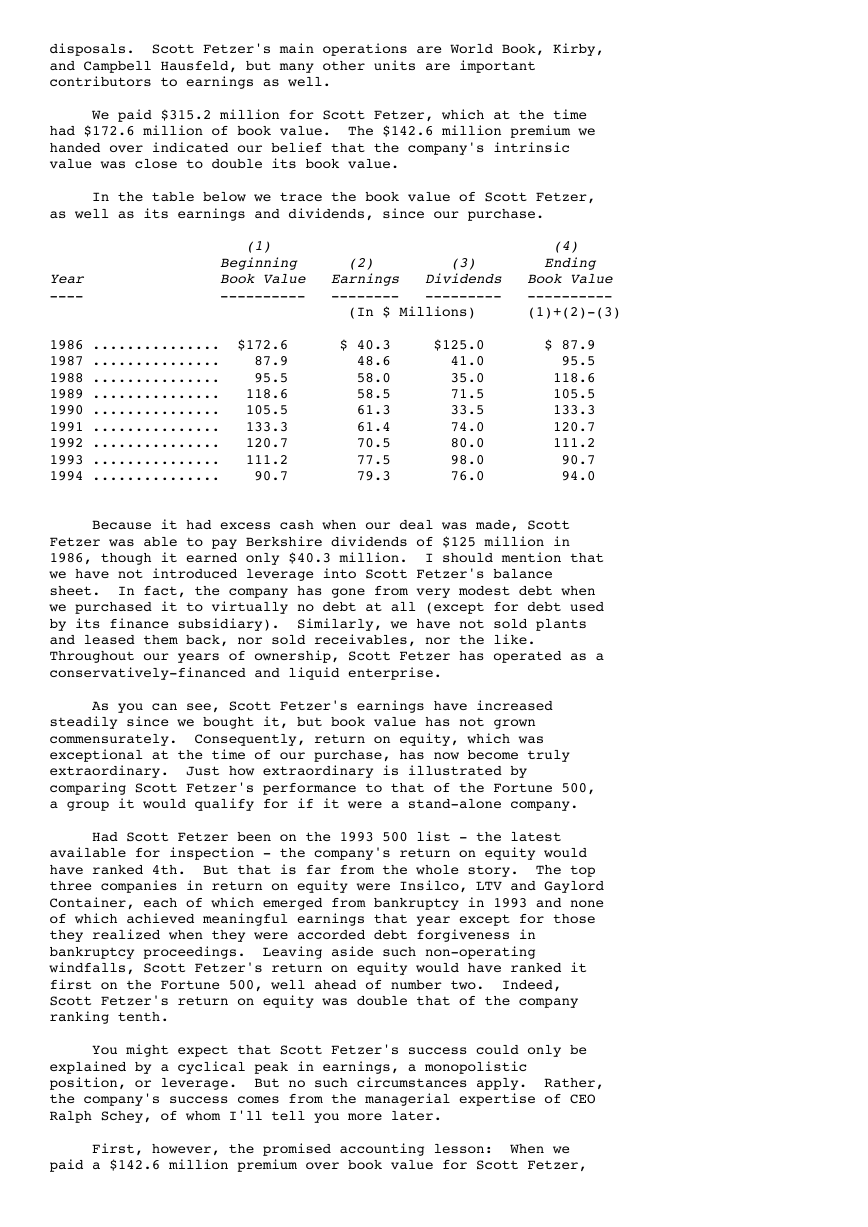

Sources of Reported Earnings

The table on the next page shows the main sources of

Berkshire's reported earnings. In this presentation, purchase-

premium charges of the type we discussed in our earlier analysis

of Scott Fetzer are not assigned to the specific businesses to

which they apply, but are instead aggregated and shown

separately. This procedure lets you view the earnings of our

businesses as they would have been reported had we not purchased

them. This form of presentation seems to us to be more useful to

investors and managers than one utilizing GAAP, which requires

purchase premiums to be charged off, business-by-business. The

total earnings we show in the table are, of course, identical to

the GAAP total in our audited financial statements.

Berkshire's Share

of Net Earnings

(after taxes and

Pre-Tax Earnings minority interests)

------------------- -------------------

�