7

1

0

2

n

u

J

9

1

]

L

C

.

s

c

[

2

v

2

6

7

3

0

.

6

0

7

1

:

v

i

X

r

a

Attention Is All You Need

Ashish Vaswani∗

Google Brain

avaswani@google.com

Noam Shazeer∗

Google Brain

noam@google.com

Niki Parmar∗

Google Research

nikip@google.com

Jakob Uszkoreit∗

Google Research

usz@google.com

Llion Jones∗

Google Research

llion@google.com

Aidan N. Gomez∗†

University of Toronto

aidan@cs.toronto.edu

Łukasz Kaiser∗

Google Brain

lukaszkaiser@google.com

Illia Polosukhin∗‡

illia.polosukhin@gmail.com

Abstract

The dominant sequence transduction models are based on complex recurrent or

convolutional neural networks that include an encoder and a decoder. The best

performing models also connect the encoder and decoder through an attention

mechanism. We propose a new simple network architecture, the Transformer,

based solely on attention mechanisms, dispensing with recurrence and convolutions

entirely. Experiments on two machine translation tasks show these models to

be superior in quality while being more parallelizable and requiring significantly

less time to train. Our model achieves 28.4 BLEU on the WMT 2014 English-

to-German translation task, improving over the existing best results, including

ensembles, by over 2 BLEU. On the WMT 2014 English-to-French translation task,

our model establishes a new single-model state-of-the-art BLEU score of 41.2 after

training for 4.5 days on eight GPUs, a small fraction of the training costs of the

best models from the literature. We show that the Transformer generalizes well to

other tasks by applying it successfully to English constituency parsing both with

large and limited training data.

1

Introduction

Recurrent neural networks, long short-term memory [13] and gated recurrent [7] neural networks

in particular, have been firmly established as state of the art approaches in sequence modeling and

transduction problems such as language modeling and machine translation [33, 2, 5]. Numerous

efforts have since continued to push the boundaries of recurrent language models and encoder-decoder

architectures [36, 23, 15].

Recurrent models typically factor computation along the symbol positions of the input and output

sequences. Aligning the positions to steps in computation time, they generate a sequence of hidden

states ht, as a function of the previous hidden state ht−1 and the input for position t. This inherently

sequential nature precludes parallelization within training examples, which becomes critical at longer

∗Equal contribution. Listing order is random.

†Work performed while at Google Brain.

‡Work performed while at Google Research.

Code available at https://github.com/tensorflow/tensor2tensor

�

sequence lengths, as memory constraints limit batching across examples. Recent work has achieved

significant improvements in computational efficiency through factorization tricks [20] and conditional

computation [31], while also improving model performance in case of the latter. The fundamental

constraint of sequential computation, however, remains.

Attention mechanisms have become an integral part of compelling sequence modeling and transduc-

tion models in various tasks, allowing modeling of dependencies without regard to their distance in

the input or output sequences [2, 18]. In all but a few cases [26], however, such attention mechanisms

are used in conjunction with a recurrent network.

In this work we propose the Transformer, a model architecture eschewing recurrence and instead

relying entirely on an attention mechanism to draw global dependencies between input and output.

The Transformer allows for significantly more parallelization and can reach a new state of the art in

translation quality after being trained for as little as twelve hours on eight P100 GPUs.

2 Background

The goal of reducing sequential computation also forms the foundation of the Extended Neural GPU

[22], ByteNet [17] and ConvS2S [9], all of which use convolutional neural networks as basic building

block, computing hidden representations in parallel for all input and output positions. In these models,

the number of operations required to relate signals from two arbitrary input or output positions grows

in the distance between positions, linearly for ConvS2S and logarithmically for ByteNet. This makes

it more difficult to learn dependencies between distant positions [12]. In the Transformer this is

reduced to a constant number of operations, albeit at the cost of reduced effective resolution due

to averaging attention-weighted positions, an effect we counteract with Multi-Head Attention as

described in section 3.2.

Self-attention, sometimes called intra-attention is an attention mechanism relating different positions

of a single sequence in order to compute a representation of the sequence. Self-attention has been

used successfully in a variety of tasks including reading comprehension, abstractive summarization,

textual entailment and learning task-independent sentence representations [4, 26, 27, 21].

To the best of our knowledge, however, the Transformer is the first transduction model relying

entirely on self-attention to compute representations of its input and output without using RNNs or

convolution. In the following sections, we will describe the Transformer, motivate self-attention and

discuss its advantages over models such as [16, 17] and [9].

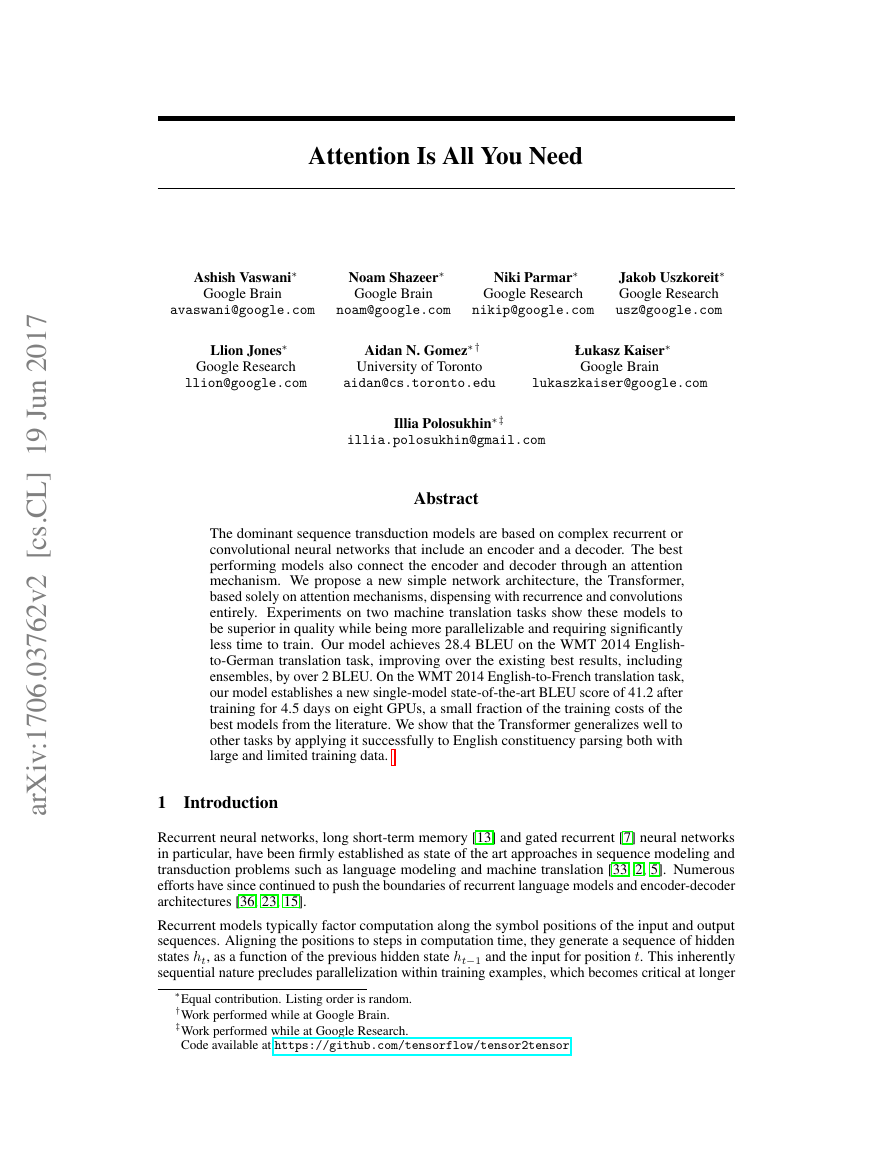

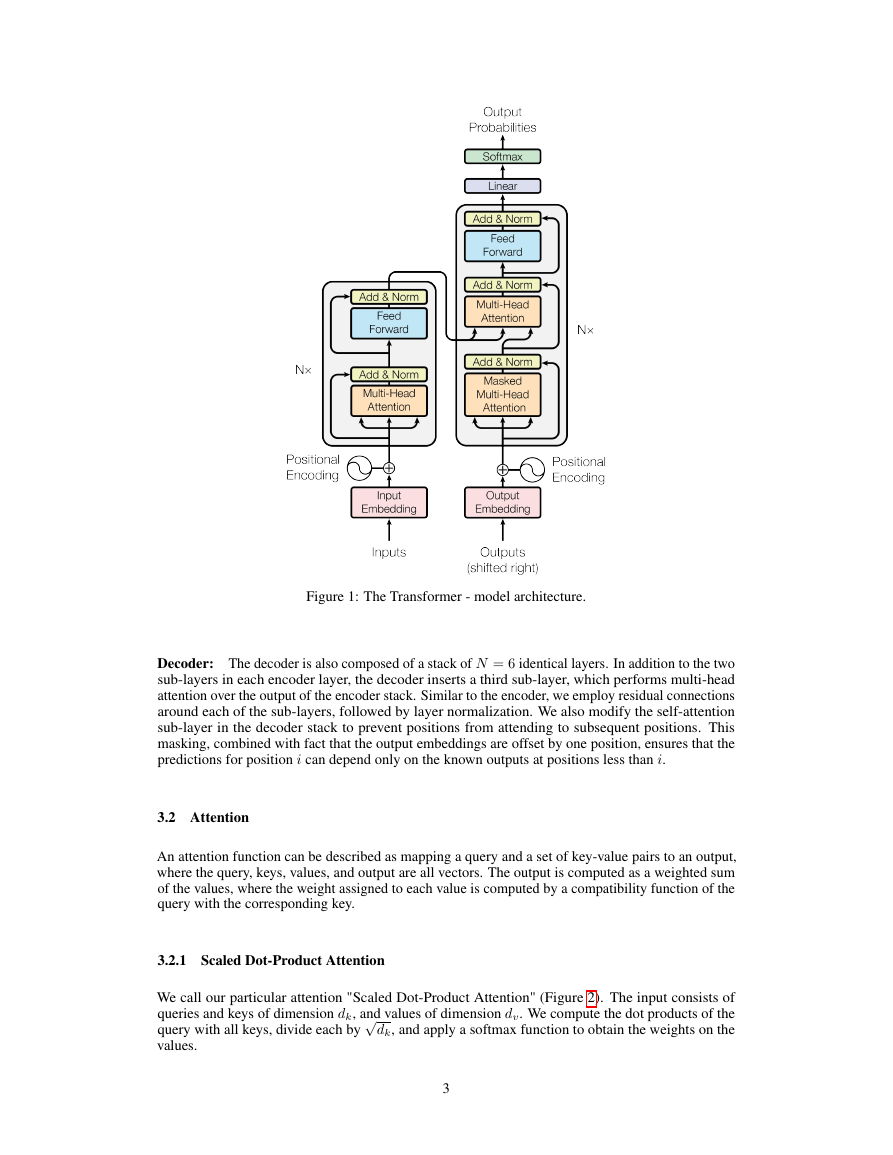

3 Model Architecture

Most competitive neural sequence transduction models have an encoder-decoder structure [5, 2, 33].

Here, the encoder maps an input sequence of symbol representations (x1, ..., xn) to a sequence

of continuous representations z = (z1, ..., zn). Given z, the decoder then generates an output

sequence (y1, ..., ym) of symbols one element at a time. At each step the model is auto-regressive

[10], consuming the previously generated symbols as additional input when generating the next.

The Transformer follows this overall architecture using stacked self-attention and point-wise, fully

connected layers for both the encoder and decoder, shown in the left and right halves of Figure 1,

respectively.

3.1 Encoder and Decoder Stacks

Encoder: The encoder is composed of a stack of N = 6 identical layers. Each layer has two

sub-layers. The first is a multi-head self-attention mechanism, and the second is a simple, position-

wise fully connected feed-forward network. We employ a residual connection [11] around each of

the two sub-layers, followed by layer normalization [1]. That is, the output of each sub-layer is

LayerNorm(x + Sublayer(x)), where Sublayer(x) is the function implemented by the sub-layer

itself. To facilitate these residual connections, all sub-layers in the model, as well as the embedding

layers, produce outputs of dimension dmodel = 512.

2

�

Figure 1: The Transformer - model architecture.

Decoder: The decoder is also composed of a stack of N = 6 identical layers. In addition to the two

sub-layers in each encoder layer, the decoder inserts a third sub-layer, which performs multi-head

attention over the output of the encoder stack. Similar to the encoder, we employ residual connections

around each of the sub-layers, followed by layer normalization. We also modify the self-attention

sub-layer in the decoder stack to prevent positions from attending to subsequent positions. This

masking, combined with fact that the output embeddings are offset by one position, ensures that the

predictions for position i can depend only on the known outputs at positions less than i.

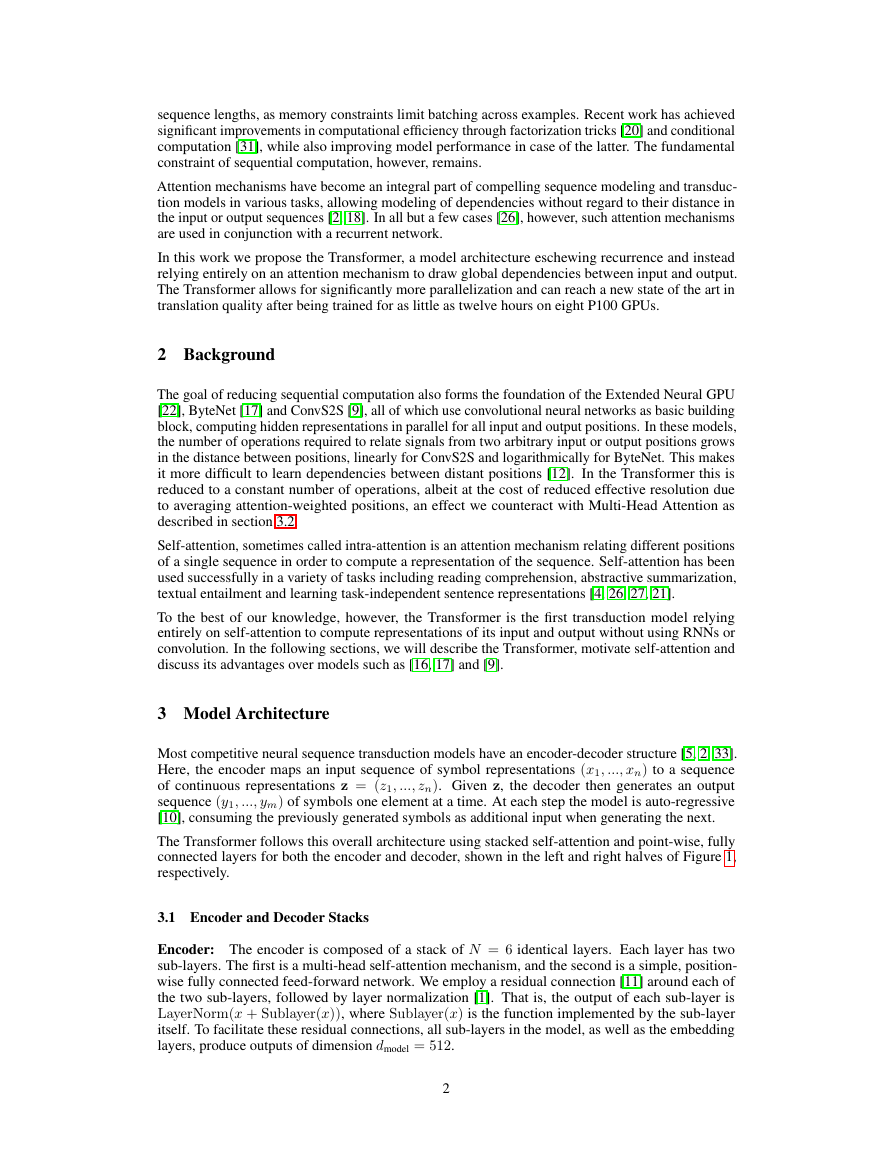

3.2 Attention

An attention function can be described as mapping a query and a set of key-value pairs to an output,

where the query, keys, values, and output are all vectors. The output is computed as a weighted sum

of the values, where the weight assigned to each value is computed by a compatibility function of the

query with the corresponding key.

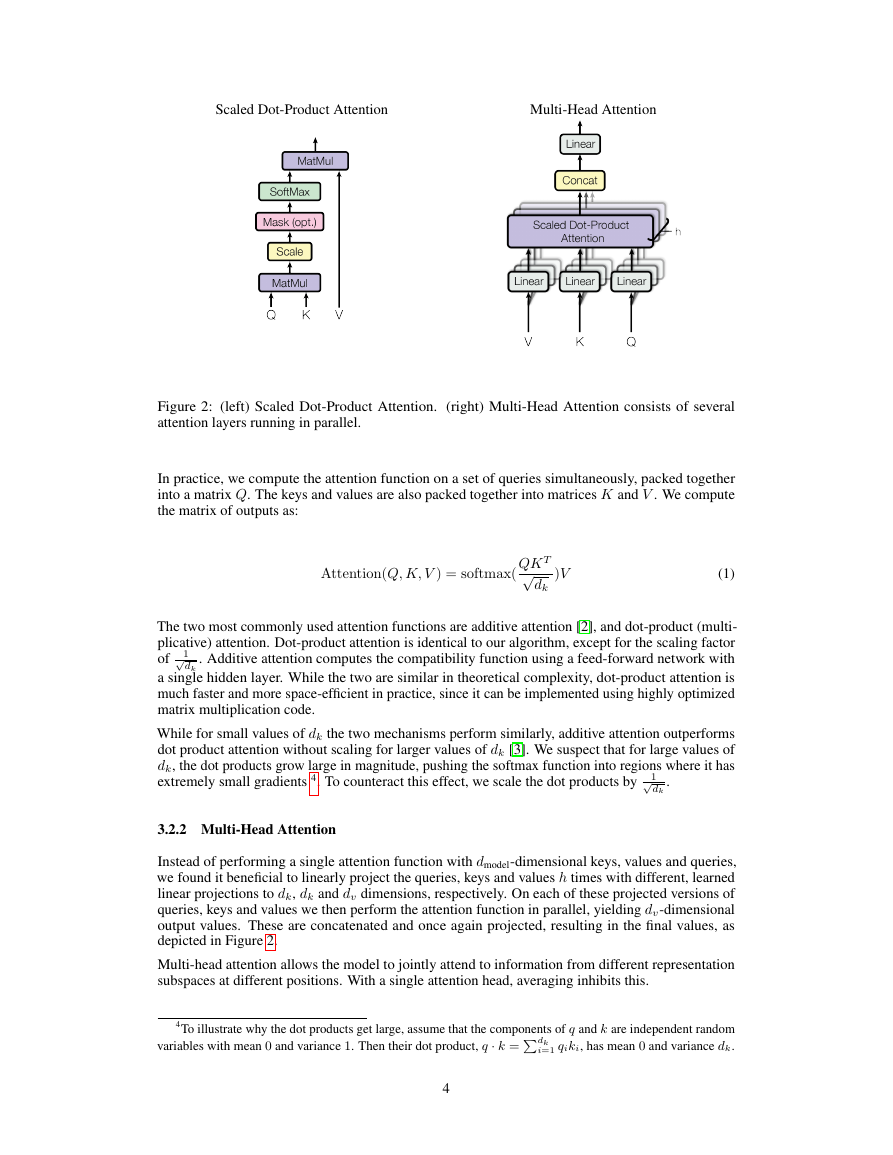

3.2.1 Scaled Dot-Product Attention

We call our particular attention "Scaled Dot-Product Attention" (Figure 2). The input consists of

queries and keys of dimension dk, and values of dimension dv. We compute the dot products of the

query with all keys, divide each by

dk, and apply a softmax function to obtain the weights on the

values.

√

3

�

Scaled Dot-Product Attention

Multi-Head Attention

Figure 2: (left) Scaled Dot-Product Attention. (right) Multi-Head Attention consists of several

attention layers running in parallel.

In practice, we compute the attention function on a set of queries simultaneously, packed together

into a matrix Q. The keys and values are also packed together into matrices K and V . We compute

the matrix of outputs as:

Attention(Q, K, V ) = softmax(

QK T√

dk

)V

(1)

1√

dk

The two most commonly used attention functions are additive attention [2], and dot-product (multi-

plicative) attention. Dot-product attention is identical to our algorithm, except for the scaling factor

of

. Additive attention computes the compatibility function using a feed-forward network with

a single hidden layer. While the two are similar in theoretical complexity, dot-product attention is

much faster and more space-efficient in practice, since it can be implemented using highly optimized

matrix multiplication code.

While for small values of dk the two mechanisms perform similarly, additive attention outperforms

dot product attention without scaling for larger values of dk [3]. We suspect that for large values of

dk, the dot products grow large in magnitude, pushing the softmax function into regions where it has

extremely small gradients 4. To counteract this effect, we scale the dot products by 1√

dk

.

3.2.2 Multi-Head Attention

Instead of performing a single attention function with dmodel-dimensional keys, values and queries,

we found it beneficial to linearly project the queries, keys and values h times with different, learned

linear projections to dk, dk and dv dimensions, respectively. On each of these projected versions of

queries, keys and values we then perform the attention function in parallel, yielding dv-dimensional

output values. These are concatenated and once again projected, resulting in the final values, as

depicted in Figure 2.

Multi-head attention allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation

subspaces at different positions. With a single attention head, averaging inhibits this.

variables with mean 0 and variance 1. Then their dot product, q · k =dk

4To illustrate why the dot products get large, assume that the components of q and k are independent random

i=1 qiki, has mean 0 and variance dk.

4

�

MultiHead(Q, K, V ) = Concat(head1, ..., headh)W O

where headi = Attention(QW Q

i , KW K

i

, V W V

i )

Where the projections are parameter matrices W Q

and W O ∈ Rhdv×dmodel.

In this work we employ h = 8 parallel attention layers, or heads. For each of these we use

dk = dv = dmodel/h = 64. Due to the reduced dimension of each head, the total computational cost

is similar to that of single-head attention with full dimensionality.

i ∈ Rdmodel×dv

i ∈ Rdmodel×dk, W K

i ∈ Rdmodel×dk, W V

3.2.3 Applications of Attention in our Model

The Transformer uses multi-head attention in three different ways:

• In "encoder-decoder attention" layers, the queries come from the previous decoder layer,

and the memory keys and values come from the output of the encoder. This allows every

position in the decoder to attend over all positions in the input sequence. This mimics the

typical encoder-decoder attention mechanisms in sequence-to-sequence models such as

[36, 2, 9].

• The encoder contains self-attention layers. In a self-attention layer all of the keys, values

and queries come from the same place, in this case, the output of the previous layer in the

encoder. Each position in the encoder can attend to all positions in the previous layer of the

encoder.

• Similarly, self-attention layers in the decoder allow each position in the decoder to attend to

all positions in the decoder up to and including that position. We need to prevent leftward

information flow in the decoder to preserve the auto-regressive property. We implement this

inside of scaled dot-product attention by masking out (setting to −∞) all values in the input

of the softmax which correspond to illegal connections. See Figure 2.

3.3 Position-wise Feed-Forward Networks

In addition to attention sub-layers, each of the layers in our encoder and decoder contains a fully

connected feed-forward network, which is applied to each position separately and identically. This

consists of two linear transformations with a ReLU activation in between.

FFN(x) = max(0, xW1 + b1)W2 + b2

(2)

While the linear transformations are the same across different positions, they use different parameters

from layer to layer. Another way of describing this is as two convolutions with kernel size 1.

The dimensionality of input and output is dmodel = 512, and the inner-layer has dimensionality

df f = 2048.

In the appendix, we describe how the position-wise feed-forward network can also be seen as a form

of attention.

3.4 Embeddings and Softmax

Similarly to other sequence transduction models, we use learned embeddings to convert the input

tokens and output tokens to vectors of dimension dmodel. We also use the usual learned linear transfor-

mation and softmax function to convert the decoder output to predicted next-token probabilities. In

our model, we share the same weight matrix between the two embedding layers and the pre-softmax

linear transformation, similar to [29]. In the embedding layers, we multiply those weights by

dmodel.

√

3.5 Positional Encoding

Since our model contains no recurrence and no convolution, in order for the model to make use of the

order of the sequence, we must inject some information about the relative or absolute position of the

5

�

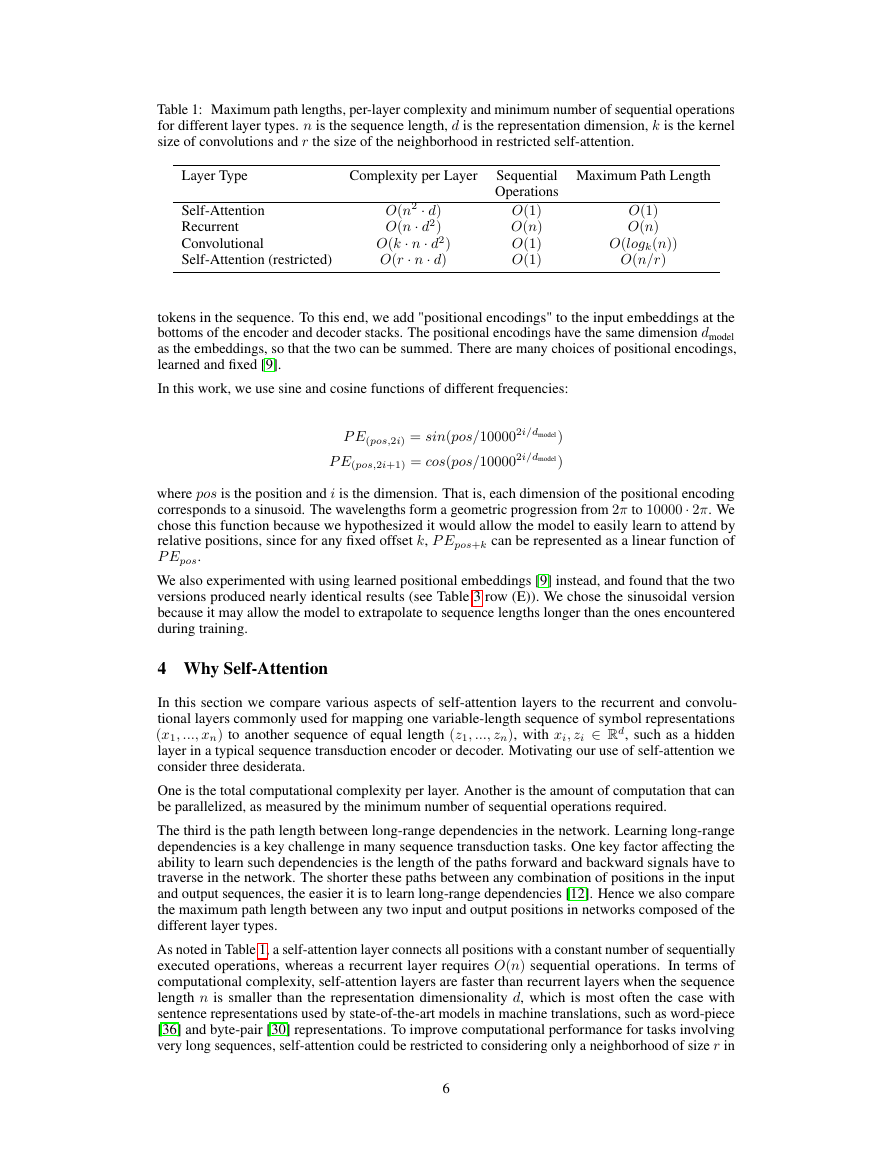

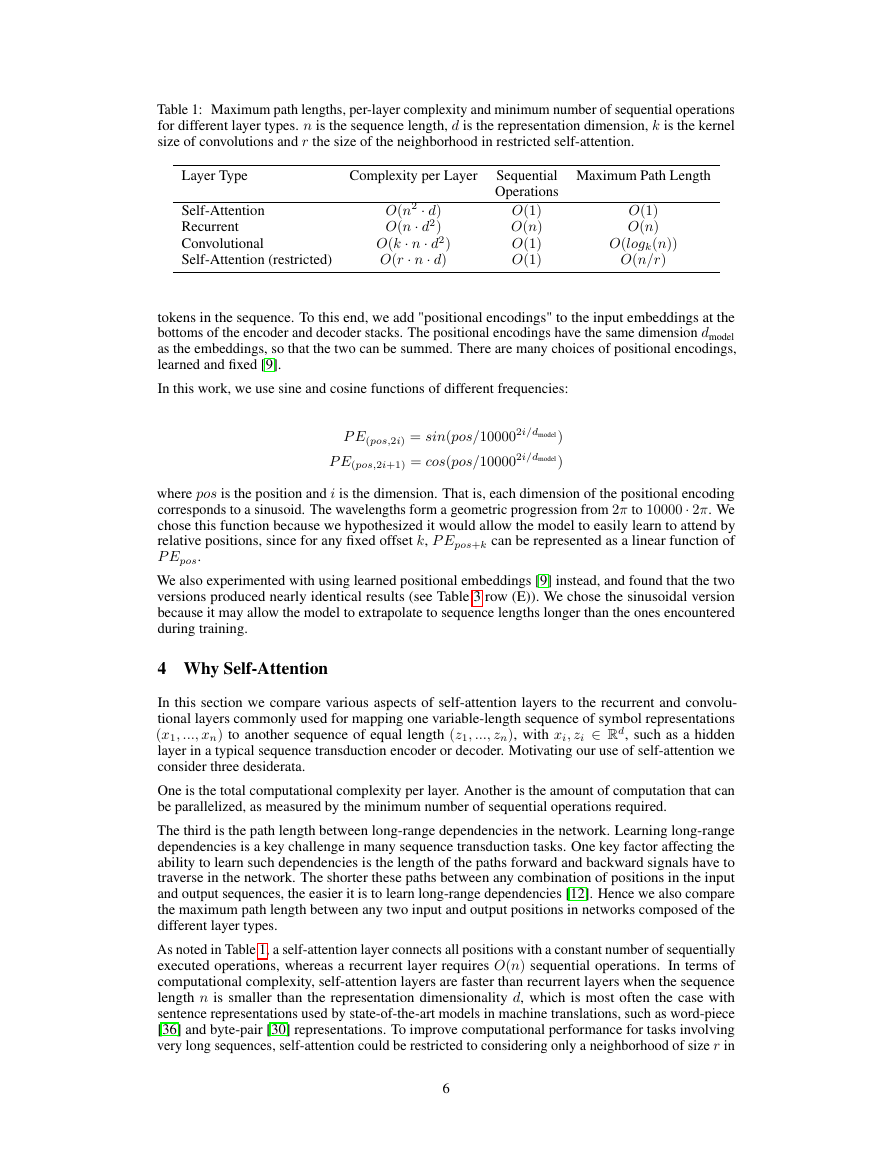

Table 1: Maximum path lengths, per-layer complexity and minimum number of sequential operations

for different layer types. n is the sequence length, d is the representation dimension, k is the kernel

size of convolutions and r the size of the neighborhood in restricted self-attention.

Layer Type

Complexity per Layer

Self-Attention

Recurrent

Convolutional

Self-Attention (restricted)

O(n2 · d)

O(n · d2)

O(k · n · d2)

O(r · n · d)

Sequential Maximum Path Length

Operations

O(1)

O(n)

O(1)

O(1)

O(1)

O(n)

O(logk(n))

O(n/r)

tokens in the sequence. To this end, we add "positional encodings" to the input embeddings at the

bottoms of the encoder and decoder stacks. The positional encodings have the same dimension dmodel

as the embeddings, so that the two can be summed. There are many choices of positional encodings,

learned and fixed [9].

In this work, we use sine and cosine functions of different frequencies:

P E(pos,2i) = sin(pos/100002i/dmodel)

P E(pos,2i+1) = cos(pos/100002i/dmodel)

where pos is the position and i is the dimension. That is, each dimension of the positional encoding

corresponds to a sinusoid. The wavelengths form a geometric progression from 2π to 10000 · 2π. We

chose this function because we hypothesized it would allow the model to easily learn to attend by

relative positions, since for any fixed offset k, P Epos+k can be represented as a linear function of

P Epos.

We also experimented with using learned positional embeddings [9] instead, and found that the two

versions produced nearly identical results (see Table 3 row (E)). We chose the sinusoidal version

because it may allow the model to extrapolate to sequence lengths longer than the ones encountered

during training.

4 Why Self-Attention

In this section we compare various aspects of self-attention layers to the recurrent and convolu-

tional layers commonly used for mapping one variable-length sequence of symbol representations

(x1, ..., xn) to another sequence of equal length (z1, ..., zn), with xi, zi ∈ Rd, such as a hidden

layer in a typical sequence transduction encoder or decoder. Motivating our use of self-attention we

consider three desiderata.

One is the total computational complexity per layer. Another is the amount of computation that can

be parallelized, as measured by the minimum number of sequential operations required.

The third is the path length between long-range dependencies in the network. Learning long-range

dependencies is a key challenge in many sequence transduction tasks. One key factor affecting the

ability to learn such dependencies is the length of the paths forward and backward signals have to

traverse in the network. The shorter these paths between any combination of positions in the input

and output sequences, the easier it is to learn long-range dependencies [12]. Hence we also compare

the maximum path length between any two input and output positions in networks composed of the

different layer types.

As noted in Table 1, a self-attention layer connects all positions with a constant number of sequentially

executed operations, whereas a recurrent layer requires O(n) sequential operations. In terms of

computational complexity, self-attention layers are faster than recurrent layers when the sequence

length n is smaller than the representation dimensionality d, which is most often the case with

sentence representations used by state-of-the-art models in machine translations, such as word-piece

[36] and byte-pair [30] representations. To improve computational performance for tasks involving

very long sequences, self-attention could be restricted to considering only a neighborhood of size r in

6

�

the input sequence centered around the respective output position. This would increase the maximum

path length to O(n/r). We plan to investigate this approach further in future work.

A single convolutional layer with kernel width k < n does not connect all pairs of input and output

positions. Doing so requires a stack of O(n/k) convolutional layers in the case of contiguous kernels,

or O(logk(n)) in the case of dilated convolutions [17], increasing the length of the longest paths

between any two positions in the network. Convolutional layers are generally more expensive than

recurrent layers, by a factor of k. Separable convolutions [6], however, decrease the complexity

considerably, to O(k · n · d + n · d2). Even with k = n, however, the complexity of a separable

convolution is equal to the combination of a self-attention layer and a point-wise feed-forward layer,

the approach we take in our model.

As side benefit, self-attention could yield more interpretable models. We inspect attention distributions

from our models and present and discuss examples in the appendix. Not only do individual attention

heads clearly learn to perform different tasks, many appear to exhibit behavior related to the syntactic

and semantic structure of the sentences.

5 Training

This section describes the training regime for our models.

5.1 Training Data and Batching

We trained on the standard WMT 2014 English-German dataset consisting of about 4.5 million

sentence pairs. Sentences were encoded using byte-pair encoding [3], which has a shared source-

target vocabulary of about 37000 tokens. For English-French, we used the significantly larger WMT

2014 English-French dataset consisting of 36M sentences and split tokens into a 32000 word-piece

vocabulary [36]. Sentence pairs were batched together by approximate sequence length. Each training

batch contained a set of sentence pairs containing approximately 25000 source tokens and 25000

target tokens.

5.2 Hardware and Schedule

We trained our models on one machine with 8 NVIDIA P100 GPUs. For our base models using

the hyperparameters described throughout the paper, each training step took about 0.4 seconds. We

trained the base models for a total of 100,000 steps or 12 hours. For our big models,(described on the

bottom line of table 3), step time was 1.0 seconds. The big models were trained for 300,000 steps

(3.5 days).

5.3 Optimizer

We used the Adam optimizer [19] with β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.98 and � = 10−9. We varied the learning

rate over the course of training, according to the formula:

lrate = d−0.5

model · min(step_num−0.5, step_num · warmup_steps−1.5)

(3)

This corresponds to increasing the learning rate linearly for the first warmup_steps training steps,

and decreasing it thereafter proportionally to the inverse square root of the step number. We used

warmup_steps = 4000.

5.4 Regularization

We employ three types of regularization during training:

Residual Dropout We apply dropout [32] to the output of each sub-layer, before it is added to the

sub-layer input and normalized. In addition, we apply dropout to the sums of the embeddings and the

positional encodings in both the encoder and decoder stacks. For the base model, we use a rate of

Pdrop = 0.1.

7

�

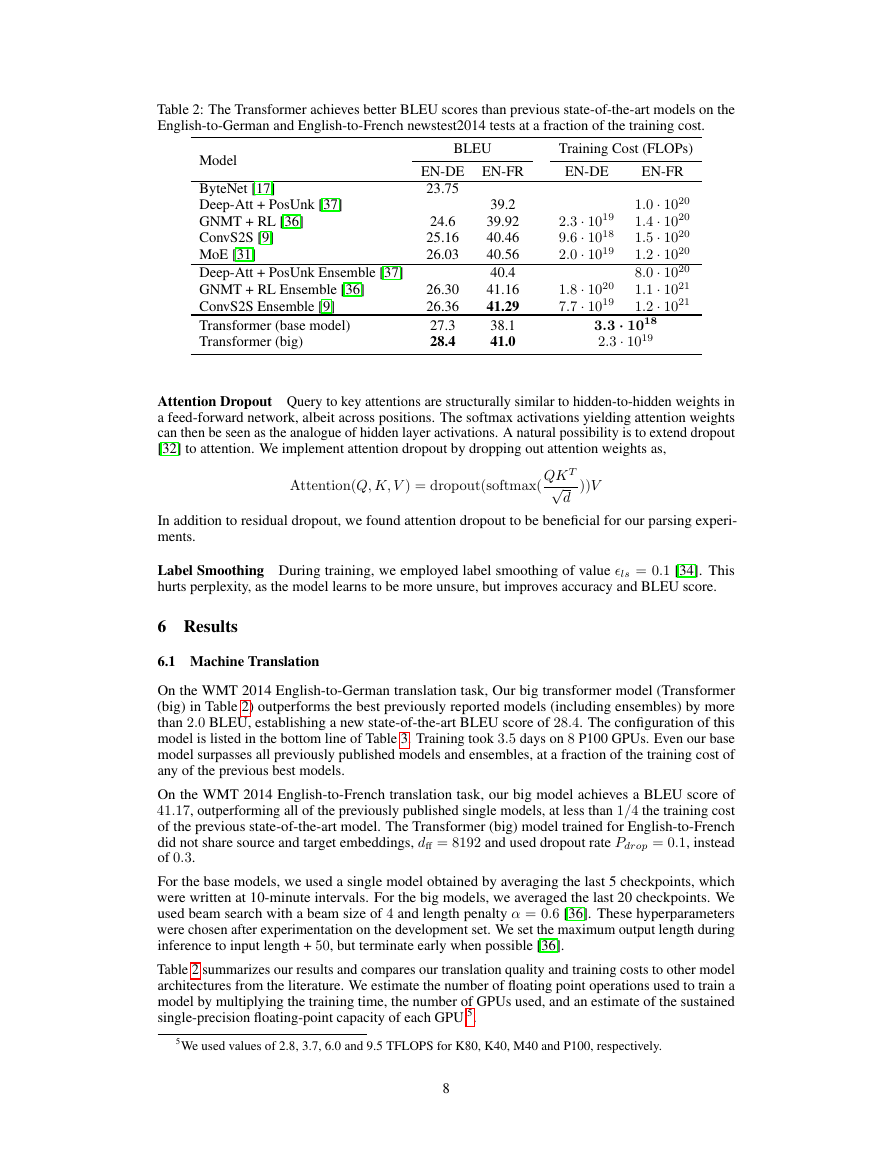

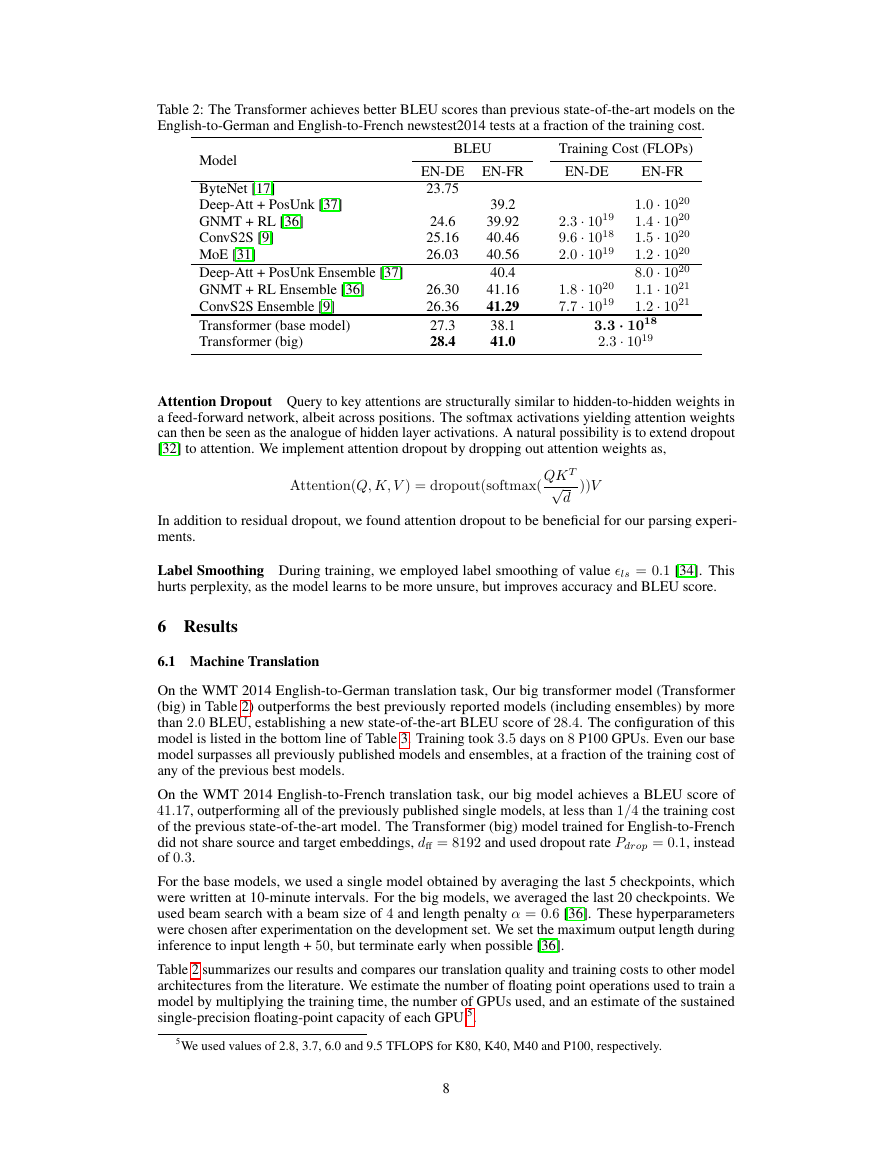

Table 2: The Transformer achieves better BLEU scores than previous state-of-the-art models on the

English-to-German and English-to-French newstest2014 tests at a fraction of the training cost.

Model

ByteNet [17]

Deep-Att + PosUnk [37]

GNMT + RL [36]

ConvS2S [9]

MoE [31]

Deep-Att + PosUnk Ensemble [37]

GNMT + RL Ensemble [36]

ConvS2S Ensemble [9]

Transformer (base model)

Transformer (big)

BLEU

EN-DE EN-FR

23.75

24.6

25.16

26.03

26.30

26.36

27.3

28.4

39.2

39.92

40.46

40.56

40.4

41.16

41.29

38.1

41.0

EN-FR

1.0 · 1020

1.4 · 1020

1.5 · 1020

1.2 · 1020

8.0 · 1020

1.1 · 1021

1.2 · 1021

2.3 · 1019

9.6 · 1018

2.0 · 1019

1.8 · 1020

7.7 · 1019

Training Cost (FLOPs)

EN-DE

3.3 · 1018

2.3 · 1019

Attention Dropout Query to key attentions are structurally similar to hidden-to-hidden weights in

a feed-forward network, albeit across positions. The softmax activations yielding attention weights

can then be seen as the analogue of hidden layer activations. A natural possibility is to extend dropout

[32] to attention. We implement attention dropout by dropping out attention weights as,

Attention(Q, K, V ) = dropout(softmax(

QK T√

d

))V

In addition to residual dropout, we found attention dropout to be beneficial for our parsing experi-

ments.

Label Smoothing During training, we employed label smoothing of value �ls = 0.1 [34]. This

hurts perplexity, as the model learns to be more unsure, but improves accuracy and BLEU score.

6 Results

6.1 Machine Translation

On the WMT 2014 English-to-German translation task, Our big transformer model (Transformer

(big) in Table 2) outperforms the best previously reported models (including ensembles) by more

than 2.0 BLEU, establishing a new state-of-the-art BLEU score of 28.4. The configuration of this

model is listed in the bottom line of Table 3. Training took 3.5 days on 8 P100 GPUs. Even our base

model surpasses all previously published models and ensembles, at a fraction of the training cost of

any of the previous best models.

On the WMT 2014 English-to-French translation task, our big model achieves a BLEU score of

41.17, outperforming all of the previously published single models, at less than 1/4 the training cost

of the previous state-of-the-art model. The Transformer (big) model trained for English-to-French

did not share source and target embeddings, dff = 8192 and used dropout rate Pdrop = 0.1, instead

of 0.3.

For the base models, we used a single model obtained by averaging the last 5 checkpoints, which

were written at 10-minute intervals. For the big models, we averaged the last 20 checkpoints. We

used beam search with a beam size of 4 and length penalty α = 0.6 [36]. These hyperparameters

were chosen after experimentation on the development set. We set the maximum output length during

inference to input length + 50, but terminate early when possible [36].

Table 2 summarizes our results and compares our translation quality and training costs to other model

architectures from the literature. We estimate the number of floating point operations used to train a

model by multiplying the training time, the number of GPUs used, and an estimate of the sustained

single-precision floating-point capacity of each GPU 5.

5We used values of 2.8, 3.7, 6.0 and 9.5 TFLOPS for K80, K40, M40 and P100, respectively.

8

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc