毕 业 设 计(论文)

外 文 文 献 翻 译

文献、资料中文题目:安卓应用基础

文献、资料英文题目:Android Application Fundamentals

文献、资料来源:

文献、资料发表(出版)日期:

院 (部):

专

班

姓

学

业:

级:

名:

号:

指导教师:

翻译日期: 2017.02.14

�

英语原文

Android Application Fundamentals

Android applications are written in the Java programming language. The Android SDK

tools compile the code—along with any data and resource files—into an Android package, an

archive file with an .apk suffix. All the code in a single .apk file is considered to be one

application and is the file that Android-powered devices use to install the application.

Once installed on a device, each Android application lives in its own security sandbox:

The Android operating system is a multi-user Linux system in which each

application is a different user.

By default, the system assigns each application a unique Linux user ID (the ID is

used only by the system and is unknown to the application). The system sets

permissions for all the files in an application so that only the user ID assigned to that

application can access them.

Each process has its own virtual machine (VM), so an application's code runs in

isolation from other applications.

By default, every application runs in its own Linux process. Android starts the

process when any of the application's components need to be executed, then shuts

down the process when it's no longer needed or when the system must recover

memory for other applications.

In this way, the Android system implements the principle of least privilege. That is, each

application, by default, has access only to the components that it requires to do its work and

no more. This creates a very secure environment in which an application cannot access parts

of the system for which it is not given permission.

However, there are ways for an application to share data with other applications and for

an application to access system services:

It's possible to arrange for two applications to share the same Linux user ID, in which

case they are able to access each other's files. To conserve system resources,

applications with the same user ID can also arrange to run in the same Linux process

�

and share the same VM (the applications must also be signed with the same

certificate).

An application can request permission to access device data such as the user's

contacts, SMS messages, the mountable storage (SD card), camera, Bluetooth, and

more. All application permissions must be granted by the user at install time.

That covers the basics regarding how an Android application exists within the system. The

rest of this document introduces you to:

The core framework components that define your application.

The manifest file in which you declare components and required device features for

your application.

Resources that are separate from the application code and allow your application to

gracefully optimize its behavior for a variety of device configurations.

Application Components

Application components are the essential building blocks of an Android application. Each

component is a different point through which the system can enter your application. Not all

components are actual entry points for the user and some depend on each other, but each one

exists as its own entity and plays a specific role—each one is a unique building block that

helps define your application's overall behavior.

There are four different types of application components. Each type serves a distinct purpose

and has a distinct lifecycle that defines how the component is created and destroyed.

Here are the four types of application components:

Activities

An activity represents a single screen with a user interface. For example, an email

application might have one activity that shows a list of new emails, another activity to

compose an email, and another activity for reading emails. Although the activities

work together to form a cohesive user experience in the email application, each one is

independent of the others. As such, a different application can start any one of these

activities (if the email application allows it). For example, a camera application can

start the activity in the email application that composes new mail, in order for the user

to share a picture.

�

An activity is implemented as a subclass of Activity and you can learn more about it in

the Activities developer guide.

Services

A service is a component that runs in the background to perform long-running

operations or to perform work for remote processes. A service does not provide a user

interface. For example, a service might play music in the background while the user is

in a different application, or it might fetch data over the network without blocking user

interaction with an activity. Another component, such as an activity, can start the

service and let it run or bind to it in order to interact with it.

A service is implemented as a subclass of Service and you can learn more about it in

the Services developer guide.

Content providers

A content provider manages a shared set of application data. You can store the data in

the file system, an SQLite database, on the web, or any other persistent storage

location your application can access. Through the content provider, other applications

can query or even modify the data (if the content provider allows it). For example, the

Android system provides a content provider

that manages the user's contact

information. As such, any application with the proper permissions can query part of

the content provider (such as ContactsContract.Data) to read and write information

about a particular person.

Content providers are also useful for reading and writing data that is private to your

application and not shared. For example, the Note Pad sample application uses a

content provider to save notes.

A content provider is implemented as a subclass of ContentProvider and must

implement a standard set of APIs that enable other applications to perform transactions.

For more information, see the Content Providers developer guide.

Broadcast receivers

receiver

that

is a component

responds to system-wide broadcast

A broadcast

announcements. Many broadcasts originate from the system—for example, a

broadcast announcing that the screen has turned off, the battery is low, or a picture was

�

captured. Applications can also initiate broadcasts—for example,

to let other

applications know that some data has been downloaded to the device and is available

for them to use. Although broadcast receivers don't display a user interface, they

may create a status bar notification to alert the user when a broadcast event occurs.

More commonly, though, a broadcast receiver is just a "gateway" to other components

and is intended to do a very minimal amount of work. For instance, it might initiate a

service to perform some work based on the event.

A broadcast receiver is implemented as a subclass of BroadcastReceiver and each

broadcast

see

theBroadcastReceiver class.

object. For more

information,

an

Intent

is

delivered

as

A unique aspect of the Android system design is that any application can start another

application’s component. For example, if you want the user to capture a photo with the device

camera, there's probably another application that does that and your application can use it,

instead of developing an activity to capture a photo yourself. You don't need to incorporate or

even link to the code from the camera application. Instead, you can simply start the activity in

the camera application that captures a photo. When complete, the photo is even returned to

your application so you can use it. To the user, it seems as if the camera is actually a part of

your application.

When the system starts a component, it starts the process for that application (if it's not

already running) and instantiates the classes needed for the component. For example, if your

application starts the activity in the camera application that captures a photo, that activity runs

in the process that belongs to the camera application, not in your application's process.

Therefore, unlike applications on most other systems, Android applications don't have a single

entry point (there's no main() function, for example).

Because the system runs each application in a separate process with file permissions that

restrict access to other applications, your application cannot directly activate a component

from another application. The Android system, however, can. So, to activate a component in

another application, you must deliver a message to the system that specifies your intent to

start a particular component. The system then activates the component for you.

Activating Components

�

Three of the four component types—activities, services, and broadcast receivers—are

activated by an asynchronous message called an intent. Intents bind individual components to

each other at runtime (you can think of them as the messengers that request an action from

other components), whether the component belongs to your application or another.

An intent is created with an Intent object, which defines a message to activate either a

specific component or a specific type of component—an intent can be either explicit or

implicit, respectively.

For activities and services, an intent defines the action to perform (for example, to "view"

or "send" something) and may specify the URI of the data to act on (among other things that

the component being started might need to know). For example, an intent might convey a

request for an activity to show an image or to open a web page. In some cases, you can start

an activity to receive a result, in which case, the activity also returns the result in

an Intent (for example, you can issue an intent to let the user pick a personal contact and have

it returned to you—the return intent includes a URI pointing to the chosen contact).

For broadcast receivers, the intent simply defines the announcement being broadcast (for

example, a broadcast to indicate the device battery is low includes only a known action string

that indicates "battery is low").

The other component type, content provider, is not activated by intents. Rather, it is

activated when targeted by a request from a ContentResolver. The content resolver handles all

direct transactions with the content provider so that the component that's performing

transactions with the provider doesn't need to and instead calls methods on

the ContentResolver object. This leaves a layer of abstraction between the content provider

and the component requesting information (for security).

There are separate methods for activating each type of component:

You can start an activity (or give it something new to do) by passing

an Intent to startActivity() or startActivityForResult() (when you want the activity to

return a result).

You can start a service (or give new instructions to an ongoing service) by passing

an Intent to startService(). Or you can bind to the service by passing

an Intent tobindService().

�

You can initiate a broadcast by passing an Intent to methods

like sendBroadcast(), sendOrderedBroadcast(), or sendStickyBroadcast().

You can perform a query to a content provider by calling query() on

a ContentResolver.

For more information about using intents, see the Intents and Intent Filters document.

More information about activating specific components is also provided in the following

documents: Activities, Services, BroadcastReceiver and Content Providers.

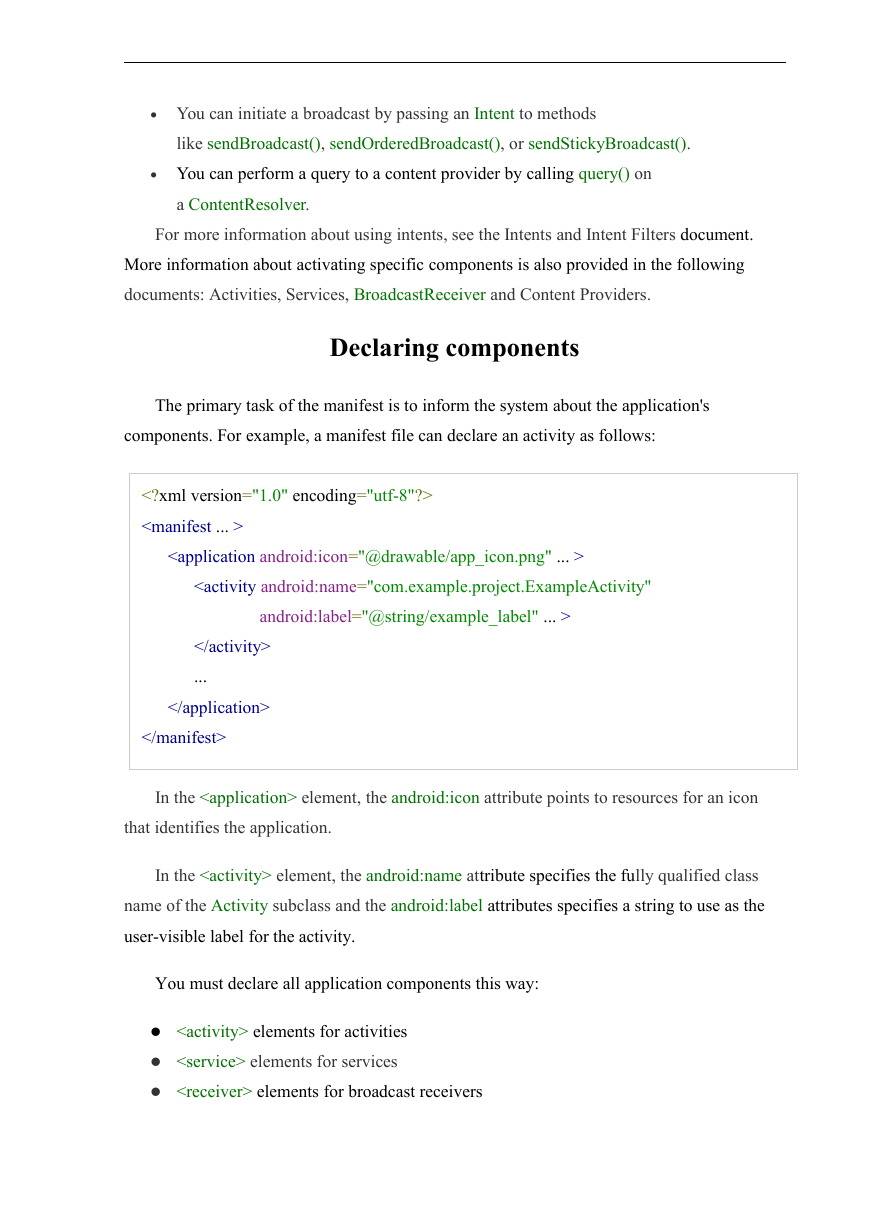

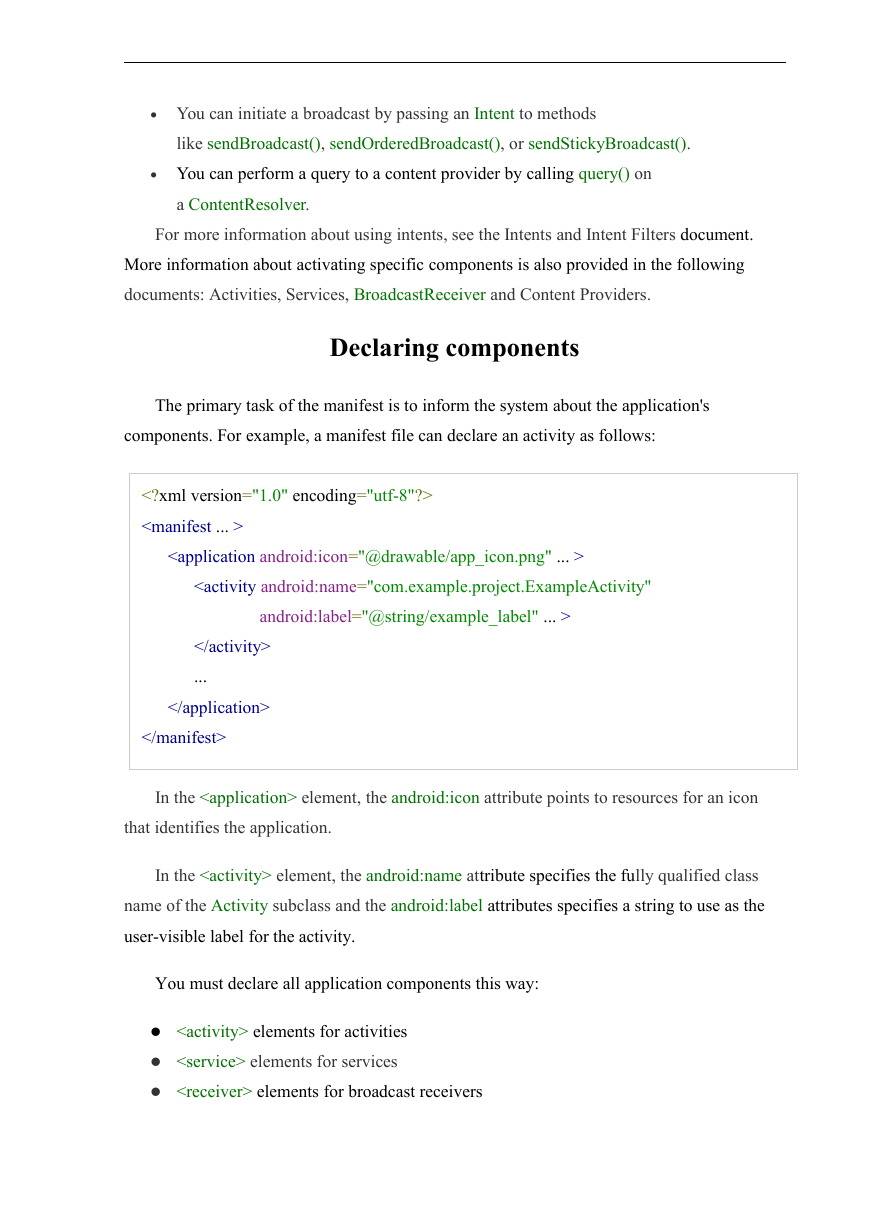

Declaring components

The primary task of the manifest is to inform the system about the application's

components. For example, a manifest file can declare an activity as follows:

...

In the

element, the android:icon attribute points to resources for an icon

that identifies the application.

In the element, the android:name attribute specifies the fully qualified class

name of the Activity subclass and the android:label attributes specifies a string to use as the

user-visible label for the activity.

You must declare all application components this way:

elements for activities

elements for services

elements for broadcast receivers

�

elements for content providers

Activities, services, and content providers that you include in your source but do not

declare in the manifest are not visible to the system and, consequently, can never run.

However, broadcast receivers can be either declared in the manifest or created dynamically in

code (as BroadcastReceiver objects) and registered with the system by

calling registerReceiver().

Declaring component capabilities

As discussed above, in Activating Components, you can use an Intent to start activities,

services, and broadcast receivers. You can do so by explicitly naming the target component

(using the component class name) in the intent. However, the real power of intents lies in the

concept of intent actions. With intent actions, you simply describe the type of action you want

to perform (and optionally, the data upon which you’d like to perform the action) and allow

the system to find a component on the device that can perform the action and start it. If there

are multiple components that can perform the action described by the intent, then the user

selects which one to use.

The way the system identifies the components that can respond to an intent is by

comparing the intent received to the intent filters provided in the manifest file of other

applications on the device.

When you declare a component in your application's manifest, you can optionally include

intent filters that declare the capabilities of the component so it can respond to intents from

other applications. You can declare an intent filter for your component by adding

an element as a child of the component's declaration element.

For example, an email application with an activity for composing a new email might

declare an intent filter in its manifest entry to respond to "send" intents (in order to send

email). An activity in your application can then create an intent with the “send” action

(ACTION_SEND), which the system matches to the email application’s “send” activity and

launches it when you invoke the intent with startActivity().

For more about creating intent filters, see the Intents and Intent Filters document.

Declaring application requirements

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc