Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

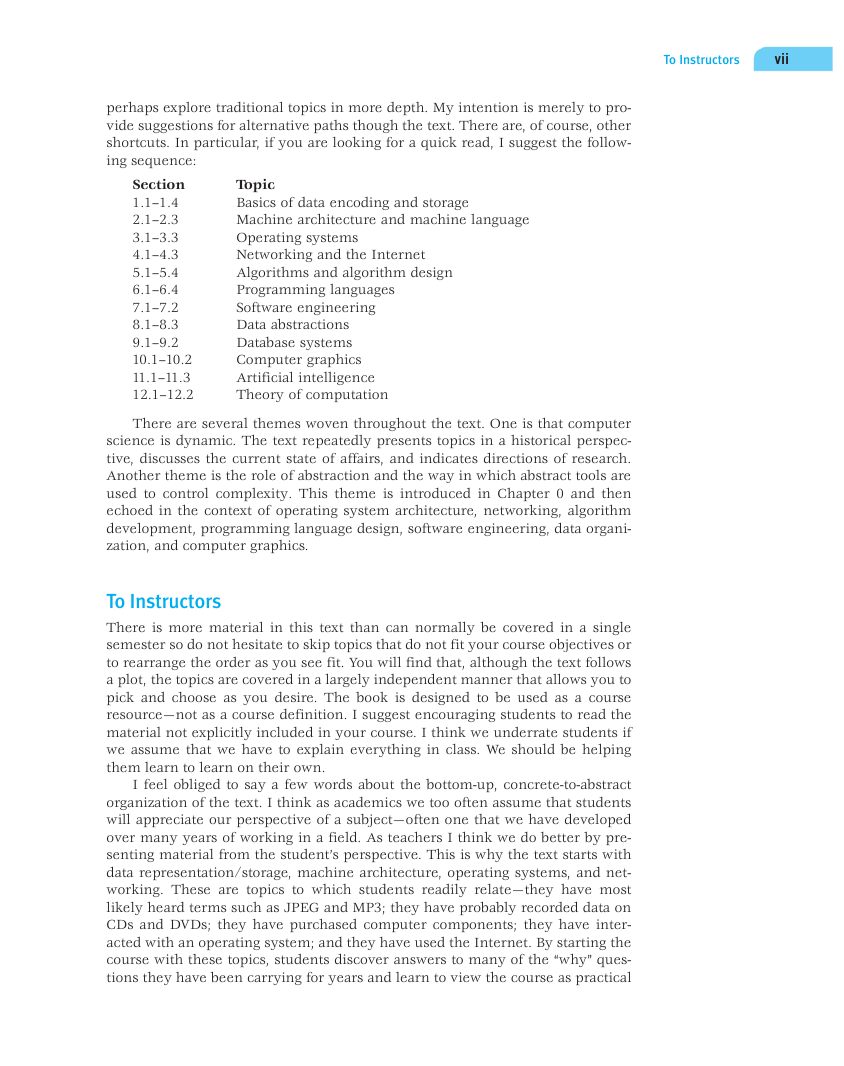

Preface

Acknowledgments

Contents

Chapter 0 Introduction

0.1 The Role of Algorithms

0.2 The History of Computing

0.3 The Science of Algorithms

0.4 Abstraction

0.5 An Outline of Our Study

0.6 Social Repercussions

Chapter 1 Data Storage

1.1 Bits and Their Storage

Boolean Operations

Gates and Flip-Flops

Hexadecimal Notation

1.2 Main Memory

Memory Organization

Measuring Memory Capacity

1.3 Mass Storage

Magnetic Systems

Optical Systems

Flash Drives

File Storage and Retrieval

1.4 Representing Information as Bit Patterns

Representing Text

Representing Numeric Values

Representing Images

Representing Sound

1.5 The Binary System

Binary Notation

Binary Addition

Fractions in Binary

1.6 Storing Integers

Two’s Complement Notation

Excess Notation

1.7 Storing Fractions

Floating-Point Notation

Truncation Errors

1.8 Data Compression

Generic Data Compression Techniques

Compressing Images

Compressing Audio and Video

1.9 Communication Errors

Parity Bits

Error-Correcting Codes

Chapter 2 Data Manipulation

2.1 Computer Architecture

CPU Basics

The Stored-Program Concept

2.2 Machine Language

The Instruction Repertoire

An Illustrative Machine Language

2.3 Program Execution

An Example of Program Execution

Programs Versus Data

2.4 Arithmetic/Logic Instructions

Logic Operations

Rotation and Shift Operations

Arithmetic Operations

2.5 Communicating with Other Devices

The Role of Controllers

Direct Memory Access

Handshaking

Popular Communication Media

Communication Rates

2.6 Other Architectures

Pipelining

Multiprocessor Machines

Chapter 3 Operating Systems

3.1 The History of Operating Systems

3.2 Operating System Architecture

A Software Survey

Components of an Operating System

Getting It Started

3.3 Coordinating the Machine’s Activities

The Concept of a Process

Process Administration

3.4 Handling Competition Among Processes

Semaphores

Deadlock

3.5 Security

Attacks from the Outside

Attacks from Within

Chapter 4 Networking and the Internet

4.1 Network Fundamentals

Network Classifications

Protocols

Combining Networks

Methods of Process Communication

Distributed Systems

4.2 The Internet

Internet Architecture

Internet Addressing

Internet Applications

4.3 The World Wide Web

Web Implementation

HTML

XML

Client-Side and Server-Side Activities

4.4 Internet Protocols

The Layered Approach to Internet Software

The TCP/IP Protocol Suite

4.5 Security

Forms of Attack

Protection and Cures

Encryption

Legal Approaches to Network Security

Chapter 5 Algorithms

5.1 The Concept of an Algorithm

An Informal Review

The Formal Definition of an Algorithm

The Abstract Nature of Algorithms

5.2 Algorithm Representation

Primitives

Pseudocode

5.3 Algorithm Discovery

The Art of Problem Solving

Getting a Foot in the Door

5.4 Iterative Structures

The Sequential Search Algorithm

Loop Control

The Insertion Sort Algorithm

5.5 Recursive Structures

The Binary Search Algorithm

Recursive Control

5.6 Efficiency and Correctness

Algorithm Efficiency

Software Verification

Chapter 6 Programming Languages

6.1 Historical Perspective

Early Generations

Machine Independence and Beyond

Programming Paradigms

6.2 Traditional Programming Concepts

Variables and Data Types

Data Structure

Constants and Literals

Assignment Statements

Control Statements

Comments

6.3 Procedural Units

Procedures

Parameters

Functions

6.4 Language Implementation

The Translation Process

Software Development Packages

6.5 Object-Oriented Programming

Classes and Objects

Constructors

Additional Features

6.6 Programming Concurrent Activities

6.7 Declarative Programming

Logical Deduction

Prolog

Chapter 7 Software Engineering

7.1 The Software Engineering Discipline

7.2 The Software Life Cycle

The Cycle as a Whole

The Traditional Development Phase

7.3 Software Engineering Methodologies

7.4 Modularity

Modular Implementation

Coupling

Cohesion

Information Hiding

Components

7.5 Tools of the Trade

Some Old Friends

Unified Modeling Language

Design Patterns

7.6 Quality Assurance

The Scope of Quality Assurance

Software Testing

7.7 Documentation

7.8 The Human-Machine Interface

7.9 Software Ownership and Liability

Chapter 8 Data Abstractions

8.1 Basic Data Structures

Arrays

Lists, Stacks, and Queues

Trees

8.2 Related Concepts

Abstraction Again

Static Versus Dynamic Structures

Pointers

8.3 Implementing Data Structures

Storing Arrays

Storing Lists

Storing Stacks and Queues

Storing Binary Trees

Manipulating Data Structures

8.4 A Short Case Study

8.5 Customized Data Types

User-Defined Data Types

Abstract Data Types

8.6 Classes and Objects

8.7 Pointers in Machine Language

Chapter 9 Database Systems

9.1 Database Fundamentals

The Significance of Database Systems

The Role of Schemas

Database Management Systems

Database Models

9.2 The Relational Model

Issues of Relational Design

Relational Operations

SQL

9.3 Object-Oriented Databases

9.4 Maintaining Database Integrity

The Commit/Rollback Protocol

Locking

9.5 Traditional File Structures

Sequential Files

Indexed Files

Hash Files

9.6 Data Mining

9.7 Social Impact of Database Technology

Chapter 10 Computer Graphics

10.1 The Scope of Computer Graphics

10.2 Overview of 3D Graphics

10.3 Modeling

Modeling Individual Objects

Modeling Entire Scenes

10.4 Rendering

Light-Surface Interaction

Clipping, Scan Conversion, and Hidden-Surface Removal

Shading

Rendering-Pipeline Hardware

10.5 Dealing with Global Lighting

Ray Tracing

Radiosity

10.6 Animation

Animation Basics

Kinematics and Dynamics

The Animation Process

Chapter 11 Artificial Intelligence

11.1 Intelligence and Machines

Intelligent Agents

Research Methodologies

The Turing Test

11.2 Perception

Understanding Images

Language Processing

11.3 Reasoning

Production Systems

Search Trees

Heuristics

11.4 Additional Areas of Research

Representing and Manipulating Knowledge

Learning

Genetic Algorithms

11.5 Artificial Neural Networks

Basic Properties

Training Artificial Neural Networks

Associative Memory

11.6 Robotics

11.7 Considering the Consequences

Chapter 12 Theory of Computation

12.1 Functions and Their Computation

12.2 Turing Machines

Turing Machine Fundamentals

The Church-Turing Thesis

12.3 Universal Programming Languages

The Bare Bones Language

Programming in Bare Bones

The Universality of Bare Bones

12.4 A Noncomputable Function

The Halting Problem

The Unsolvability of the Halting Problem

12.5 Complexity of Problems

Measuring a Problem’s Complexity

Polynomial Versus Nonpolynomial Problems

NP Problems

12.6 Public-Key Cryptography

Modular Notation

RSA Public-Key Cryptography

Appendixes

A: ASCII

B: Circuits to Manipulate Two’s Complement Representations

C: A Simple Machine Language

D: High-Level Programming Languages

E: The Equivalence of Iterative and Recursive Structures

F: Answers to Questions & Exercises

Index

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

Y

Z

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc