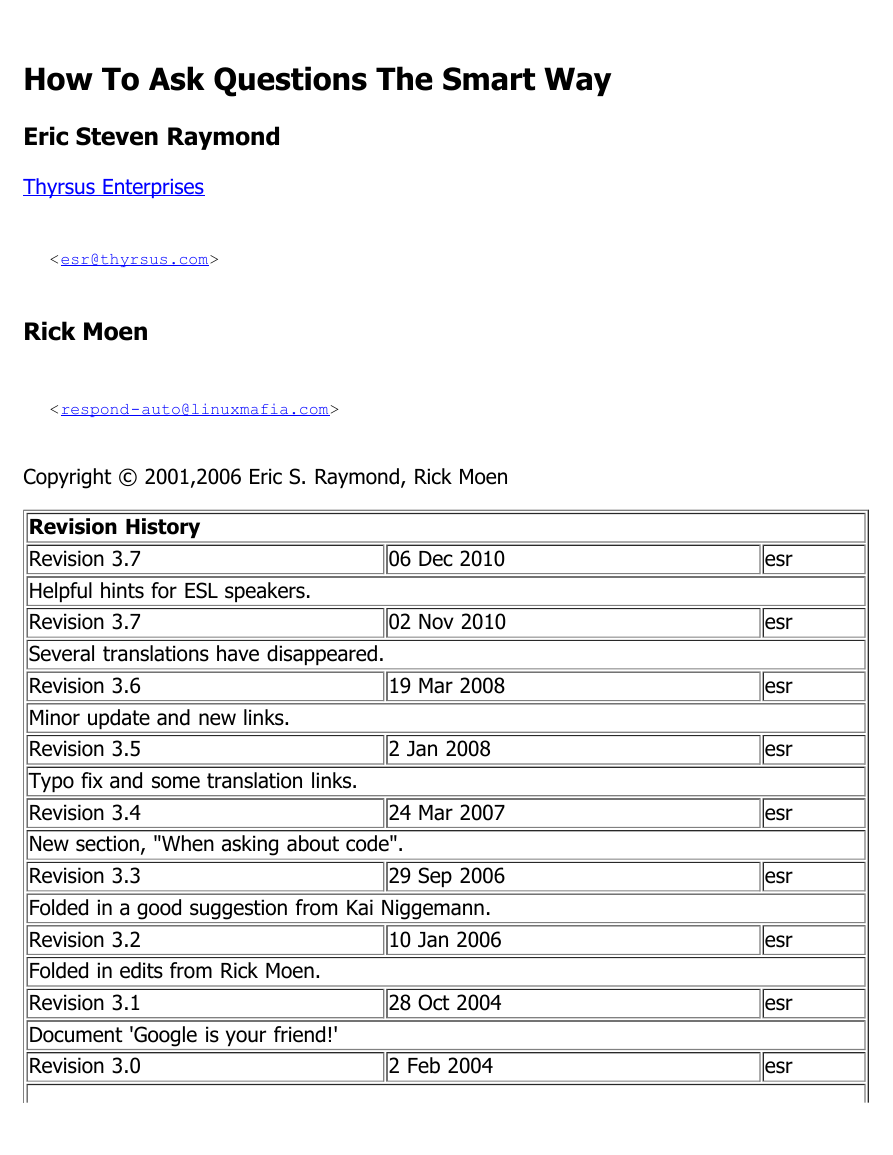

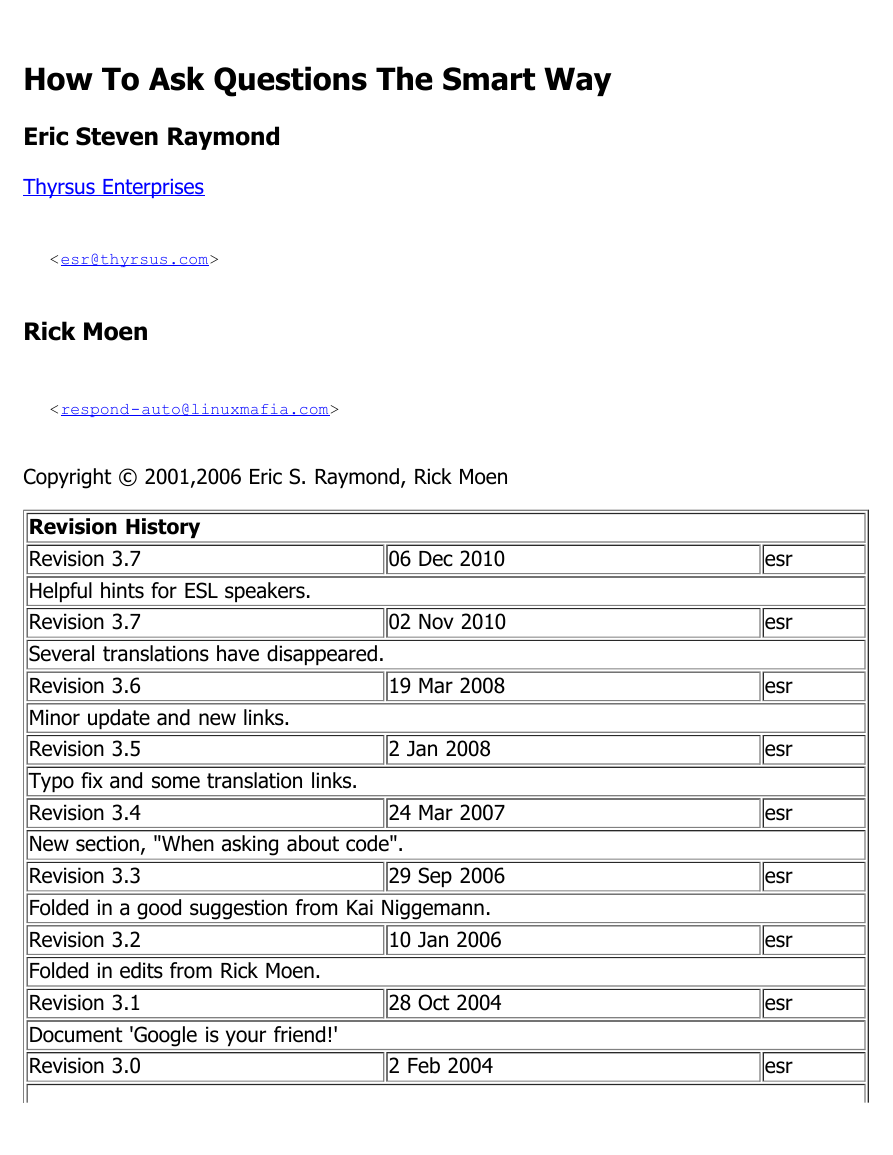

How To Ask Questions The Smart Way

Eric Steven Raymond

Thyrsus Enterprises

Rick Moen

Copyright © 2001,2006 Eric S. Raymond, Rick Moen

06 Dec 2010

02 Nov 2010

19 Mar 2008

Revision History

Revision 3.7

Helpful hints for ESL speakers.

Revision 3.7

Several translations have disappeared.

Revision 3.6

Minor update and new links.

Revision 3.5

Typo fix and some translation links.

Revision 3.4

New section, "When asking about code".

Revision 3.3

Folded in a good suggestion from Kai Niggemann.

Revision 3.2

10 Jan 2006

Folded in edits from Rick Moen.

Revision 3.1

Document 'Google is your friend!'

Revision 3.0

28 Oct 2004

2 Feb 2004

24 Mar 2007

29 Sep 2006

2 Jan 2008

esr

esr

esr

esr

esr

esr

esr

esr

esr

�

Major addition of stuff about proper etiquette on Web forums.

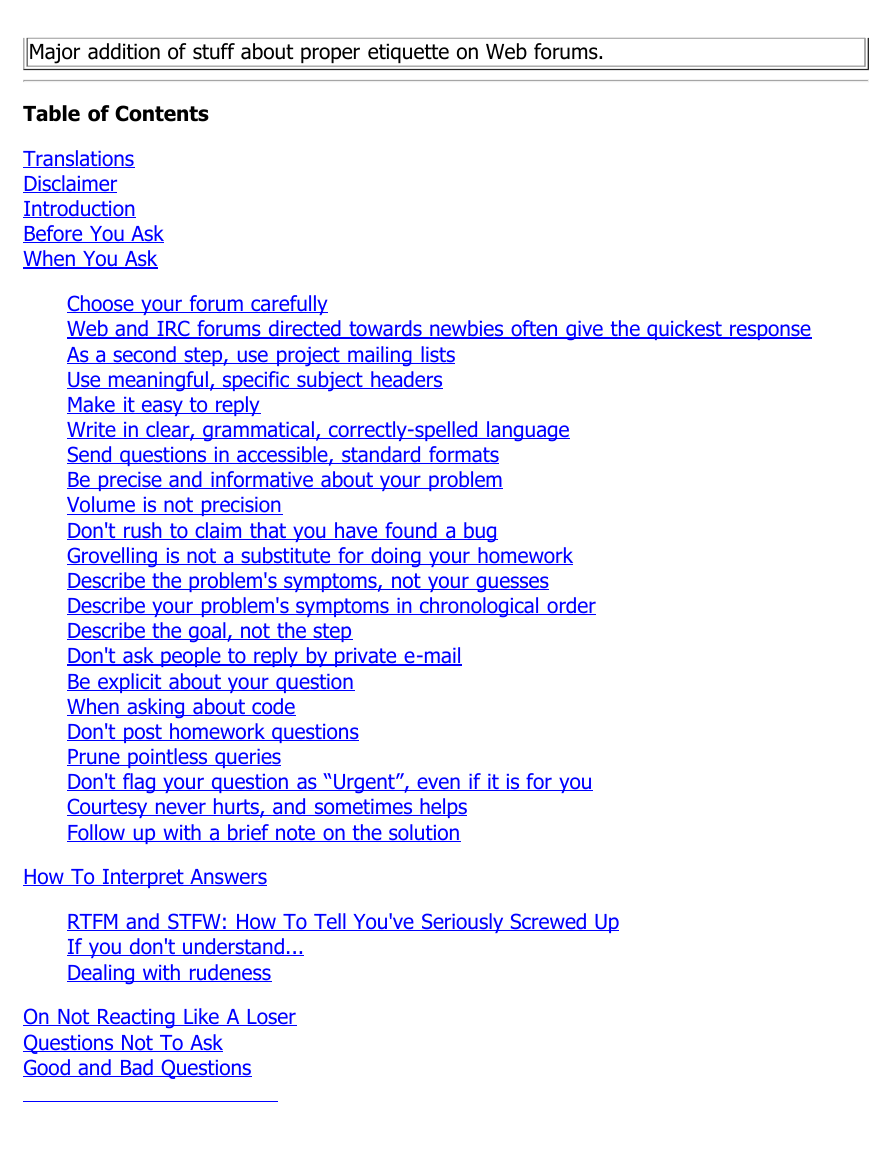

Table of Contents

Translations

Disclaimer

Introduction

Before You Ask

When You Ask

Choose your forum carefully

Web and IRC forums directed towards newbies often give the quickest response

As a second step, use project mailing lists

Use meaningful, specific subject headers

Make it easy to reply

Write in clear, grammatical, correctly-spelled language

Send questions in accessible, standard formats

Be precise and informative about your problem

Volume is not precision

Don't rush to claim that you have found a bug

Grovelling is not a substitute for doing your homework

Describe the problem's symptoms, not your guesses

Describe your problem's symptoms in chronological order

Describe the goal, not the step

Don't ask people to reply by private e-mail

Be explicit about your question

When asking about code

Don't post homework questions

Prune pointless queries

Don't flag your question as “Urgent”, even if it is for you

Courtesy never hurts, and sometimes helps

Follow up with a brief note on the solution

How To Interpret Answers

RTFM and STFW: How To Tell You've Seriously Screwed Up

If you don't understand...

Dealing with rudeness

On Not Reacting Like A Loser

Questions Not To Ask

Good and Bad Questions

�

If You Can't Get An Answer

How To Answer Questions in a Helpful Way

Related Resources

Acknowledgements

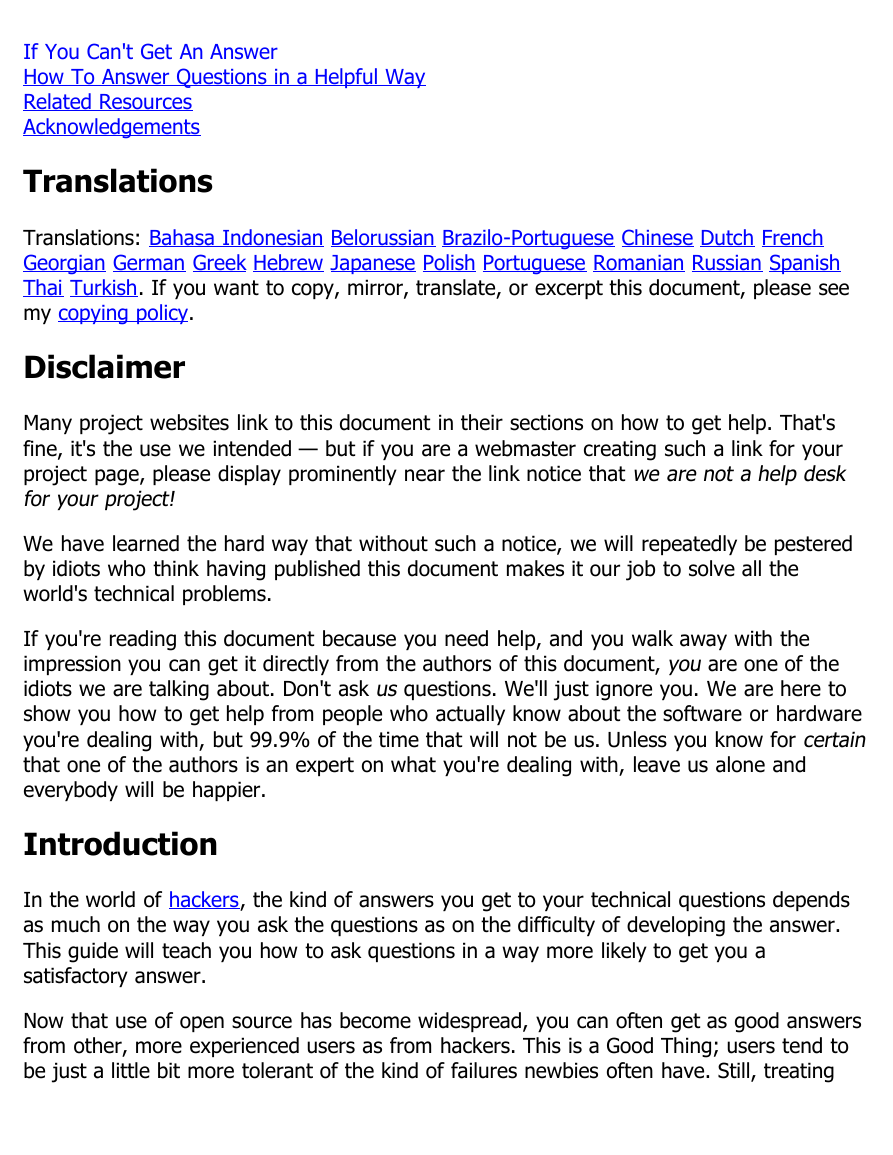

Translations

Translations: Bahasa Indonesian Belorussian Brazilo-Portuguese Chinese Dutch French

Georgian German Greek Hebrew Japanese Polish Portuguese Romanian Russian Spanish

Thai Turkish. If you want to copy, mirror, translate, or excerpt this document, please see

my copying policy.

Disclaimer

Many project websites link to this document in their sections on how to get help. That's

fine, it's the use we intended — but if you are a webmaster creating such a link for your

project page, please display prominently near the link notice that we are not a help desk

for your project!

We have learned the hard way that without such a notice, we will repeatedly be pestered

by idiots who think having published this document makes it our job to solve all the

world's technical problems.

If you're reading this document because you need help, and you walk away with the

impression you can get it directly from the authors of this document, you are one of the

idiots we are talking about. Don't ask us questions. We'll just ignore you. We are here to

show you how to get help from people who actually know about the software or hardware

you're dealing with, but 99.9% of the time that will not be us. Unless you know for certain

that one of the authors is an expert on what you're dealing with, leave us alone and

everybody will be happier.

Introduction

In the world of hackers, the kind of answers you get to your technical questions depends

as much on the way you ask the questions as on the difficulty of developing the answer.

This guide will teach you how to ask questions in a way more likely to get you a

satisfactory answer.

Now that use of open source has become widespread, you can often get as good answers

from other, more experienced users as from hackers. This is a Good Thing; users tend to

be just a little bit more tolerant of the kind of failures newbies often have. Still, treating

�

experienced users like hackers in the ways we recommend here will generally be the most

effective way to get useful answers out of them, too.

The first thing to understand is that hackers actually like hard problems and good,

thought-provoking questions about them. If we didn't, we wouldn't be here. If you give us

an interesting question to chew on we'll be grateful to you; good questions are a stimulus

and a gift. Good questions help us develop our understanding, and often reveal problems

we might not have noticed or thought about otherwise. Among hackers, “Good question!”

is a strong and sincere compliment.

Despite this, hackers have a reputation for meeting simple questions with what looks like

hostility or arrogance. It sometimes looks like we're reflexively rude to newbies and the

ignorant. But this isn't really true.

What we are, unapologetically, is hostile to people who seem to be unwilling to think or to

do their own homework before asking questions. People like that are time sinks — they

take without giving back, and they waste time we could have spent on another question

more interesting and another person more worthy of an answer. We call people like this

“losers” (and for historical reasons we sometimes spell it “lusers”).

We realize that there are many people who just want to use the software we write, and

who have no interest in learning technical details. For most people, a computer is merely a

tool, a means to an end; they have more important things to do and lives to live. We

acknowledge that, and don't expect everyone to take an interest in the technical matters

that fascinate us. Nevertheless, our style of answering questions is tuned for people who

do take such an interest and are willing to be active participants in problem-solving. That's

not going to change. Nor should it; if it did, we would become less effective at the things

we do best.

We're (largely) volunteers. We take time out of busy lives to answer questions, and at

times we're overwhelmed with them. So we filter ruthlessly. In particular, we throw away

questions from people who appear to be losers in order to spend our question-answering

time more efficiently, on winners.

If you find this attitude obnoxious, condescending, or arrogant, check your assumptions.

We're not asking you to genuflect to us — in fact, most of us would love nothing more

than to deal with you as an equal and welcome you into our culture, if you put in the

effort required to make that possible. But it's simply not efficient for us to try to help

people who are not willing to help themselves. It's OK to be ignorant; it's not OK to play

stupid.

So, while it isn't necessary to already be technically competent to get attention from us, it

is necessary to demonstrate the kind of attitude that leads to competence — alert,

�

thoughtful, observant, willing to be an active partner in developing a solution. If you can't

live with this sort of discrimination, we suggest you pay somebody for a commercial

support contract instead of asking hackers to personally donate help to you.

If you decide to come to us for help, you don't want to be one of the losers. You don't

want to seem like one, either. The best way to get a rapid and responsive answer is to ask

it like a person with smarts, confidence, and clues who just happens to need help on one

particular problem.

(Improvements to this guide are welcome. You can mail suggestions to esr@thyrsus.com

or respond-auto@linuxmafia.com. Note however that this document is not intended to be

a general guide to netiquette, and we will generally reject suggestions that are not

specifically related to eliciting useful answers in a technical forum.)

Before You Ask

Before asking a technical question by e-mail, or in a newsgroup, or on a website chat

board, do the following:

1. Try to find an answer by searching the archives of the forum you plan to post to.

2. Try to find an answer by searching the Web.

3. Try to find an answer by reading the manual.

4. Try to find an answer by reading a FAQ.

5. Try to find an answer by inspection or experimentation.

6. Try to find an answer by asking a skilled friend.

7. If you're a programmer, try to find an answer by reading the source code.

When you ask your question, display the fact that you have done these things first; this

will help establish that you're not being a lazy sponge and wasting people's time. Better

yet, display what you have learned from doing these things. We like answering questions

for people who have demonstrated they can learn from the answers.

Use tactics like doing a Google search on the text of whatever error message you get

(searching Google groups as well as Web pages). This might well take you straight to fix

documentation or a mailing list thread answering your question. Even if it doesn't, saying

“I googled on the following phrase but didn't get anything that looked promising” is a good

thing to do in e-mail or news postings requesting help, if only because it records what

searches won't help. It will also help to direct other people with similar problems to your

�

thread by linking the search terms to what will hopefully be your problem and resolution

thread.

Take your time. Do not expect to be able to solve a complicated problem with a few

seconds of Googling. Read and understand the FAQs, sit back, relax and give the problem

some thought before approaching experts. Trust us, they will be able to tell from your

questions how much reading and thinking you did, and will be more willing to help if you

come prepared. Don't instantly fire your whole arsenal of questions just because your first

search turned up no answers (or too many).

Prepare your question. Think it through. Hasty-sounding questions get hasty answers, or

none at all. The more you do to demonstrate that having put thought and effort into

solving your problem before seeking help, the more likely you are to actually get help.

Beware of asking the wrong question. If you ask one that is based on faulty assumptions,

J. Random Hacker is quite likely to reply with a uselessly literal answer while thinking

“Stupid question...”, and hoping the experience of getting what you asked for rather than

what you needed will teach you a lesson.

Never assume you are entitled to an answer. You are not; you aren't, after all, paying for

the service. You will earn an answer, if you earn it, by asking a substantial, interesting,

and thought-provoking question — one that implicitly contributes to the experience of the

community rather than merely passively demanding knowledge from others.

On the other hand, making it clear that you are able and willing to help in the process of

developing the solution is a very good start. “Would someone provide a pointer?”, “What is

my example missing?”, and “What site should I have checked?” are more likely to get

answered than “Please post the exact procedure I should use.” because you're making it

clear that you're truly willing to complete the process if someone can just point you in the

right direction.

When You Ask

Choose your forum carefully

Be sensitive in choosing where you ask your question. You are likely to be ignored, or

written off as a loser, if you:

post your question to a forum where it's off topic

post a very elementary question to a forum where advanced technical questions are

expected, or vice-versa

�

cross-post to too many different newsgroups

post a personal e-mail to somebody who is neither an acquaintance of yours nor

personally responsible for solving your problem

Hackers blow off questions that are inappropriately targeted in order to try to protect their

communications channels from being drowned in irrelevance. You don't want this to

happen to you.

The first step, therefore, is to find the right forum. Again, Google and other Web-searching

methods are your friend. Use them to find the project webpage most closely associated

with the hardware or software giving you difficulties. Usually it will have links to a FAQ

(Frequently Asked Questions) list, and to project mailing lists and their archives. These

mailing lists are the final places to go for help, if your own efforts (including reading those

FAQs you found) do not find you a solution. The project page may also describe a bug-

reporting procedure, or have a link to one; if so, follow it.

Shooting off an e-mail to a person or forum which you are not familiar with is risky at

best. For example, do not assume that the author of an informative webpage wants to be

your free consultant. Do not make optimistic guesses about whether your question will be

welcome — if you're unsure, send it elsewhere, or refrain from sending it at all.

When selecting a Web forum, newsgroup or mailing list, don't trust the name by itself too

far; look for a FAQ or charter to verify your question is on-topic. Read some of the back

traffic before posting so you'll get a feel for how things are done there. In fact, it's a very

good idea to do a keyword search for words relating to your problem on the newsgroup or

mailing list archives before you post. It may find you an answer, and if not it will help you

formulate a better question.

Don't shotgun-blast all the available help channels at once, that's like yelling and irritates

people. Step through them softly.

Know what your topic is! One of the classic mistakes is asking questions about the Unix or

Windows programming interface in a forum devoted to a language or library or tool

portable across both. If you don't understand why this is a blunder, you'd be best off not

asking any questions at all until you get it.

In general, questions to a well-selected public forum are more likely to get useful answers

than equivalent questions to a private one. There are multiple reasons for this. One is

simply the size of the pool of potential respondents. Another is the size of the audience;

hackers would rather answer questions that educate many people than questions serving

only a few.

Understandably, skilled hackers and authors of popular software are already receiving

�

more than their fair share of mis-targeted messages. By adding to the flood, you could in

extreme cases even be the straw that breaks the camel's back — quite a few times,

contributors to popular projects have withdrawn their support because collateral damage

in the form of useless e-mail traffic to their personal accounts became unbearable.

Web and IRC forums directed towards newbies often give the

quickest response

Your local user group, or your Linux distribution, may advertise a Web forum or IRC

channel where newbies can get help. (In non-English-speaking countries newbie forums

are still more likely to be mailing lists.) These are good first places to ask, especially if you

think you may have tripped over a relatively simple or common problem. An advertised

IRC channel is an open invitation to ask questions there and often get answers in real

time.

In fact, if you got the program that is giving you problems from a Linux distribution (as is

common today), it may be better to ask in the distro's forum/list before trying the

program's project forum/list. The project's hackers may just say, “use our build”.

Before posting to any Web forum, check if it has a Search feature. If it does, try a couple

of keyword searches for something like your problem; it just might help. If you did a

general Web search before (as you should have), search the forum anyway; your Web-

wide search engine might not have all of this forum indexed recently.

There is an increasing tendency for projects to do user support over a Web forum or IRC

channel, with e-mail reserved more for development traffic. So look for those channels

first when seeking project-specific help.

As a second step, use project mailing lists

When a project has a development mailing list, write to the mailing list, not to individual

developers, even if you believe you know who can best answer your question. Check the

documentation of the project and its homepage for the address of a project mailing list,

and use it. There are several good reasons for this policy:

Any question good enough to be asked of one developer will also be of value to the

whole group. Contrariwise, if you suspect your question is too dumb for a mailing list,

it's not an excuse to harass individual developers.

Asking questions on the list distributes load among developers. The individual

developer (especially if he's the project leader) may be too busy to answer your

questions.

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc