To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

This past year our registered shareholders increased from

about 1900 to about 2900. Most of this growth resulted from our

merger with Blue Chip Stamps, but there also was an acceleration

in the pace of “natural” increase that has raised us from the

1000 level a few years ago.

With so many new shareholders, it’s appropriate to summarize

the major business principles we follow that pertain to the

manager-owner relationship:

o Although our form is corporate, our attitude is

partnership. Charlie Munger and I think of our shareholders as

owner-partners, and of ourselves as managing partners. (Because

of the size of our shareholdings we also are, for better or

worse, controlling partners.) We do not view the company itself

as the ultimate owner of our business assets but, instead, view

the company as a conduit through which our shareholders own the

assets.

o In line with this owner-orientation, our directors are all

major shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway. In the case of at

least four of the five, over 50% of family net worth is

represented by holdings of Berkshire. We eat our own cooking.

o Our long-term economic goal (subject to some qualifications

mentioned later) is to maximize the average annual rate of gain

in intrinsic business value on a per-share basis. We do not

measure the economic significance or performance of Berkshire by

its size; we measure by per-share progress. We are certain that

the rate of per-share progress will diminish in the future - a

greatly enlarged capital base will see to that. But we will be

disappointed if our rate does not exceed that of the average

large American corporation.

o Our preference would be to reach this goal by directly

owning a diversified group of businesses that generate cash and

consistently earn above-average returns on capital. Our second

choice is to own parts of similar businesses, attained primarily

through purchases of marketable common stocks by our insurance

subsidiaries. The price and availability of businesses and the

need for insurance capital determine any given year’s capital

allocation.

o Because of this two-pronged approach to business ownership

and because of the limitations of conventional accounting,

consolidated reported earnings may reveal relatively little about

our true economic performance. Charlie and I, both as owners and

managers, virtually ignore such consolidated numbers. However,

we will also report to you the earnings of each major business we

control, numbers we consider of great importance. These figures,

along with other information we will supply about the individual

businesses, should generally aid you in making judgments about

them.

o Accounting consequences do not influence our operating or

capital-allocation decisions. When acquisition costs are

similar, we much prefer to purchase $2 of earnings that is not

reportable by us under standard accounting principles than to

purchase $1 of earnings that is reportable. This is precisely

the choice that often faces us since entire businesses (whose

earnings will be fully reportable) frequently sell for double the

pro-rata price of small portions (whose earnings will be largely

B

E

R

K

S

H

I

R

E

H

A

T

H

A

W

A

Y

I

N

C

.

�

unreportable). In aggregate and over time, we expect the

unreported earnings to be fully reflected in our intrinsic

business value through capital gains.

o We rarely use much debt and, when we do, we attempt to

structure it on a long-term fixed rate basis. We will reject

interesting opportunities rather than over-leverage our balance

sheet. This conservatism has penalized our results but it is the

only behavior that leaves us comfortable, considering our

fiduciary obligations to policyholders, depositors, lenders and

the many equity holders who have committed unusually large

portions of their net worth to our care.

o A managerial “wish list” will not be filled at shareholder

expense. We will not diversify by purchasing entire businesses

at control prices that ignore long-term economic consequences to

our shareholders. We will only do with your money what we would

do with our own, weighing fully the values you can obtain by

diversifying your own portfolios through direct purchases in the

stock market.

o We feel noble intentions should be checked periodically

against results. We test the wisdom of retaining earnings by

assessing whether retention, over time, delivers shareholders at

least $1 of market value for each $1 retained. To date, this

test has been met. We will continue to apply it on a five-year

rolling basis. As our net worth grows, it is more difficult to

use retained earnings wisely.

o We will issue common stock only when we receive as much in

business value as we give. This rule applies to all forms of

issuance - not only mergers or public stock offerings, but stock

for-debt swaps, stock options, and convertible securities as

well. We will not sell small portions of your company - and that

is what the issuance of shares amounts to - on a basis

inconsistent with the value of the entire enterprise.

o You should be fully aware of one attitude Charlie and I

share that hurts our financial performance: regardless of price,

we have no interest at all in selling any good businesses that

Berkshire owns, and are very reluctant to sell sub-par businesses

as long as we expect them to generate at least some cash and as

long as we feel good about their managers and labor relations.

We hope not to repeat the capital-allocation mistakes that led us

into such sub-par businesses. And we react with great caution to

suggestions that our poor businesses can be restored to

satisfactory profitability by major capital expenditures. (The

projections will be dazzling - the advocates will be sincere -

but, in the end, major additional investment in a terrible

industry usually is about as rewarding as struggling in

quicksand.) Nevertheless, gin rummy managerial behavior (discard

your least promising business at each turn) is not our style. We

would rather have our overall results penalized a bit than engage

in it.

o We will be candid in our reporting to you, emphasizing the

pluses and minuses important in appraising business value. Our

guideline is to tell you the business facts that we would want to

know if our positions were reversed. We owe you no less.

Moreover, as a company with a major communications business, it

would be inexcusable for us to apply lesser standards of

accuracy, balance and incisiveness when reporting on ourselves

than we would expect our news people to apply when reporting on

others. We also believe candor benefits us as managers: the CEO

who misleads others in public may eventually mislead himself in

private.

o Despite our policy of candor, we will discuss our

activities in marketable securities only to the extent legally

�

required. Good investment ideas are rare, valuable and subject

to competitive appropriation just as good product or business

acquisition ideas are. Therefore, we normally will not talk

about our investment ideas. This ban extends even to securities

we have sold (because we may purchase them again) and to stocks

we are incorrectly rumored to be buying. If we deny those

reports but say “no comment” on other occasions, the no-comments

become confirmation.

That completes the catechism, and we can now move on to the

high point of 1983 - the acquisition of a majority interest in

Nebraska Furniture Mart and our association with Rose Blumkin and

her family.

Nebraska Furniture Mart

Last year, in discussing how managers with bright, but

adrenalin-soaked minds scramble after foolish acquisitions, I

quoted Pascal: “It has struck me that all the misfortunes of men

spring from the single cause that they are unable to stay quietly

in one room.”

Even Pascal would have left the room for Mrs. Blumkin.

About 67 years ago Mrs. Blumkin, then 23, talked her way

past a border guard to leave Russia for America. She had no

formal education, not even at the grammar school level, and knew

no English. After some years in this country, she learned the

language when her older daughter taught her, every evening, the

words she had learned in school during the day.

In 1937, after many years of selling used clothing, Mrs.

Blumkin had saved $500 with which to realize her dream of opening

a furniture store. Upon seeing the American Furniture Mart in

Chicago - then the center of the nation’s wholesale furniture

activity - she decided to christen her dream Nebraska Furniture

Mart.

She met every obstacle you would expect (and a few you

wouldn’t) when a business endowed with only $500 and no

locational or product advantage goes up against rich, long-

entrenched competition. At one early point, when her tiny

resources ran out, “Mrs. B” (a personal trademark now as well

recognized in Greater Omaha as Coca-Cola or Sanka) coped in a way

not taught at business schools: she simply sold the furniture and

appliances from her home in order to pay creditors precisely as

promised.

Omaha retailers began to recognize that Mrs. B would offer

customers far better deals than they had been giving, and they

pressured furniture and carpet manufacturers not to sell to her.

But by various strategies she obtained merchandise and cut prices

sharply. Mrs. B was then hauled into court for violation of Fair

Trade laws. She not only won all the cases, but received

invaluable publicity. At the end of one case, after

demonstrating to the court that she could profitably sell carpet

at a huge discount from the prevailing price, she sold the judge

$1400 worth of carpet.

Today Nebraska Furniture Mart generates over $100 million of

sales annually out of one 200,000 square-foot store. No other

home furnishings store in the country comes close to that volume.

That single store also sells more furniture, carpets, and

appliances than do all Omaha competitors combined.

One question I always ask myself in appraising a business is

how I would like, assuming I had ample capital and skilled

personnel, to compete with it. I’d rather wrestle grizzlies than

compete with Mrs. B and her progeny. They buy brilliantly, they

�

operate at expense ratios competitors don’t even dream about, and

they then pass on to their customers much of the savings. It’s

the ideal business - one built upon exceptional value to the

customer that in turn translates into exceptional economics for

its owners.

Mrs. B is wise as well as smart and, for far-sighted family

reasons, was willing to sell the business last year. I had

admired both the family and the business for decades, and a deal

was quickly made. But Mrs. B, now 90, is not one to go home and

risk, as she puts it, “losing her marbles”. She remains Chairman

and is on the sales floor seven days a week. Carpet sales are

her specialty. She personally sells quantities that would be a

good departmental total for other carpet retailers.

We purchased 90% of the business - leaving 10% with members

of the family who are involved in management - and have optioned

10% to certain key young family managers.

And what managers they are. Geneticists should do

handsprings over the Blumkin family. Louie Blumkin, Mrs. B’s

son, has been President of Nebraska Furniture Mart for many years

and is widely regarded as the shrewdest buyer of furniture and

appliances in the country. Louie says he had the best teacher,

and Mrs. B says she had the best student. They’re both right.

Louie and his three sons all have the Blumkin business ability,

work ethic, and, most important, character. On top of that, they

are really nice people. We are delighted to be in partnership

with them.

Corporate Performance

During 1983 our book value increased from $737.43 per share

to $975.83 per share, or by 32%. We never take the one-year

figure very seriously. After all, why should the time required

for a planet to circle the sun synchronize precisely with the

time required for business actions to pay off? Instead, we

recommend not less than a five-year test as a rough yardstick of

economic performance. Red lights should start flashing if the

five-year average annual gain falls much below the return on

equity earned over the period by American industry in aggregate.

(Watch out for our explanation if that occurs as Goethe observed,

“When ideas fail, words come in very handy.”)

During the 19-year tenure of present management, book value

has grown from $19.46 per share to $975.83, or 22.6% compounded

annually. Considering our present size, nothing close to this

rate of return can be sustained. Those who believe otherwise

should pursue a career in sales, but avoid one in mathematics.

We report our progress in terms of book value because in our

case (though not, by any means, in all cases) it is a

conservative but reasonably adequate proxy for growth in

intrinsic business value - the measurement that really counts.

Book value’s virtue as a score-keeping measure is that it is easy

to calculate and doesn’t involve the subjective (but important)

judgments employed in calculation of intrinsic business value.

It is important to understand, however, that the two terms - book

value and intrinsic business value - have very different

meanings.

Book value is an accounting concept, recording the

accumulated financial input from both contributed capital and

retained earnings. Intrinsic business value is an economic

concept, estimating future cash output discounted to present

value. Book value tells you what has been put in; intrinsic

business value estimates what can be taken out.

An analogy will suggest the difference. Assume you spend

�

identical amounts putting each of two children through college.

The book value (measured by financial input) of each child’s

education would be the same. But the present value of the future

payoff (the intrinsic business value) might vary enormously -

from zero to many times the cost of the education. So, also, do

businesses having equal financial input end up with wide

variations in value.

At Berkshire, at the beginning of fiscal 1965 when the

present management took over, the $19.46 per share book value

considerably overstated intrinsic business value. All of that

book value consisted of textile assets that could not earn, on

average, anything close to an appropriate rate of return. In the

terms of our analogy, the investment in textile assets resembled

investment in a largely-wasted education.

Now, however, our intrinsic business value considerably

exceeds book value. There are two major reasons:

(1) Standard accounting principles require that common

stocks held by our insurance subsidiaries be stated on

our books at market value, but that other stocks we own

be carried at the lower of aggregate cost or market.

At the end of 1983, the market value of this latter

group exceeded carrying value by $70 million pre-tax,

or about $50 million after tax. This excess belongs in

our intrinsic business value, but is not included in

the calculation of book value;

(2) More important, we own several businesses that possess

economic Goodwill (which is properly includable in

intrinsic business value) far larger than the

accounting Goodwill that is carried on our balance

sheet and reflected in book value.

Goodwill, both economic and accounting, is an arcane subject

and requires more explanation than is appropriate here. The

appendix that follows this letter - “Goodwill and its

Amortization: The Rules and The Realities” - explains why

economic and accounting Goodwill can, and usually do, differ

enormously.

You can live a full and rewarding life without ever thinking

about Goodwill and its amortization. But students of investment

and management should understand the nuances of the subject. My

own thinking has changed drastically from 35 years ago when I was

taught to favor tangible assets and to shun businesses whose

value depended largely upon economic Goodwill. This bias caused

me to make many important business mistakes of omission, although

relatively few of commission.

Keynes identified my problem: “The difficulty lies not in

the new ideas but in escaping from the old ones.” My escape was

long delayed, in part because most of what I had been taught by

the same teacher had been (and continues to be) so

extraordinarily valuable. Ultimately, business experience,

direct and vicarious, produced my present strong preference for

businesses that possess large amounts of enduring Goodwill and

that utilize a minimum of tangible assets.

I recommend the Appendix to those who are comfortable with

accounting terminology and who have an interest in understanding

the business aspects of Goodwill. Whether or not you wish to

tackle the Appendix, you should be aware that Charlie and I

believe that Berkshire possesses very significant economic

Goodwill value above that reflected in our book value.

Sources of Reported Earnings

�

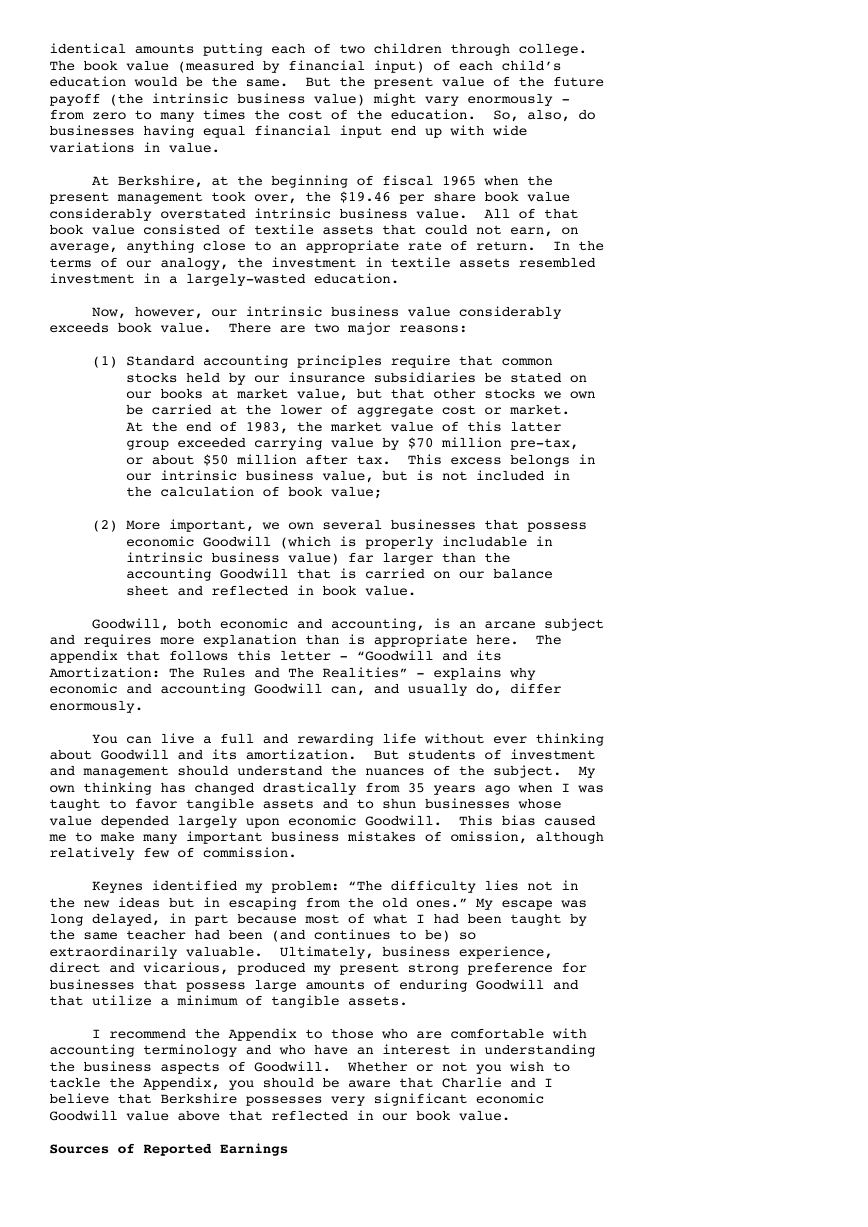

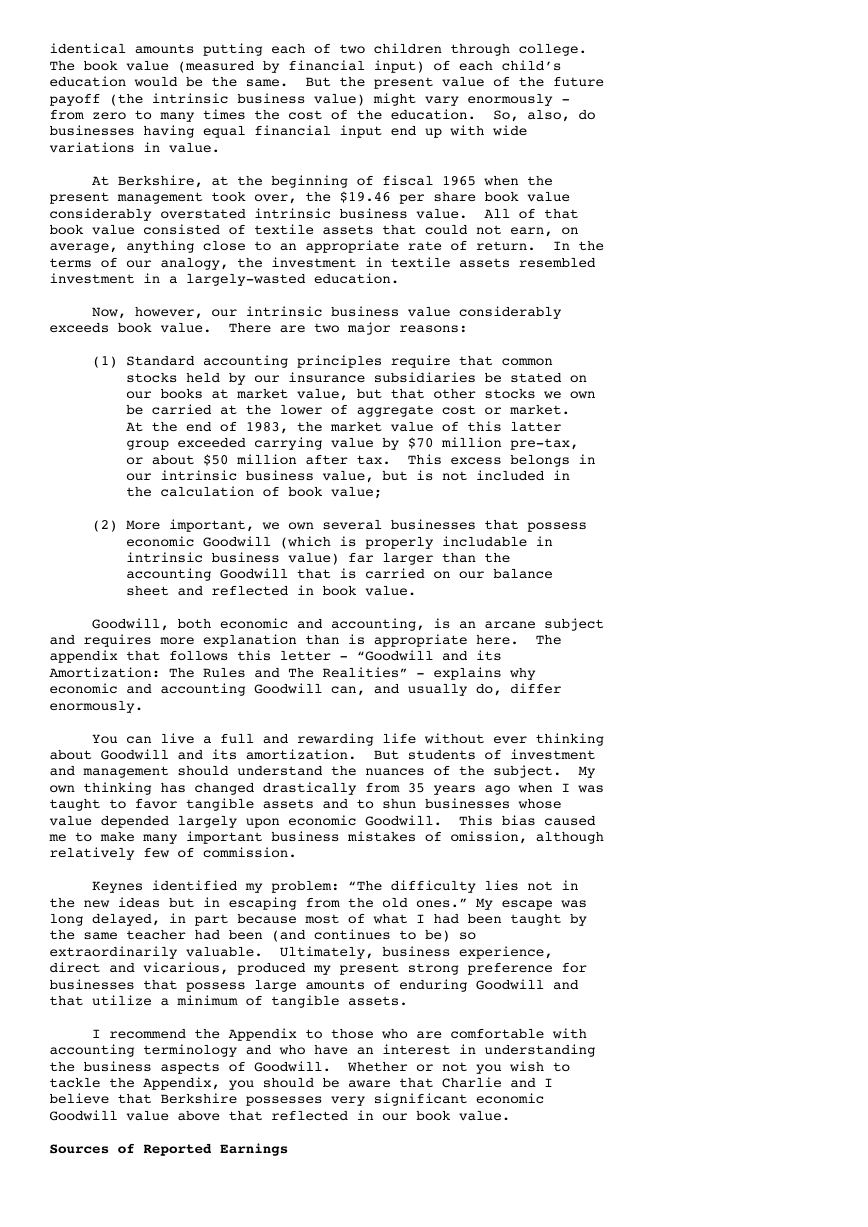

The table below shows the sources of Berkshire’s reported

earnings. In 1982, Berkshire owned about 60% of Blue Chip Stamps

whereas, in 1983, our ownership was 60% throughout the first six

months and 100% thereafter. In turn, Berkshire’s net interest in

Wesco was 48% during 1982 and the first six months of 1983, and

80% for the balance of 1983. Because of these changed ownership

percentages, the first two columns of the table provide the best

measure of underlying business performance.

All of the significant gains and losses attributable to

unusual sales of assets by any of the business entities are

aggregated with securities transactions on the line near the

bottom of the table, and are not included in operating earnings.

(We regard any annual figure for realized capital gains or losses

as meaningless, but we regard the aggregate realized and

unrealized capital gains over a period of years as very

important.) Furthermore, amortization of Goodwill is not charged

against the specific businesses but, for reasons outlined in the

Appendix, is set forth as a separate item.

Net Earnings

Earnings Before Income Taxes After Tax

-------------------------------------- ------------------

Total Berkshire Share Berkshire Share

------------------ ------------------ ------------------

1983 1982 1983 1982 1983 1982

-------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --------

(000s omitted)

Operating Earnings:

Insurance Group:

Underwriting ............ $(33,872) $(21,558) $(33,872) $(21,558) $(18,400) $(11,345)

Net Investment Income ... 43,810 41,620 43,810 41,620 39,114 35,270

Berkshire-Waumbec Textiles (100) (1,545) (100) (1,545) (63) (862)

Associated Retail Stores .. 697 914 697 914 355 446

Nebraska Furniture Mart(1) 3,812 -- 3,049 -- 1,521 --

See’s Candies ............. 27,411 23,884 24,526 14,235 12,212 6,914

Buffalo Evening News ...... 19,352 (1,215) 16,547 (724) 8,832 (226)

Blue Chip Stamps(2) ....... (1,422) 4,182 (1,876) 2,492 (353) 2,472

Wesco Financial - Parent .. 7,493 6,156 4,844 2,937 3,448 2,210

Mutual Savings and Loan ... (798) (6) (467) (2) 1,917 1,524

Precision Steel ........... 3,241 1,035 2,102 493 1,136 265

Interest on Debt .......... (15,104) (14,996) (13,844) (12,977) (7,346) (6,951)

Special GEICO Distribution 21,000 -- 21,000 -- 19,551 --

Shareholder-Designated

Contributions .......... (3,066) (891) (3,066) (891) (1,656) (481)

Amortization of Goodwill .. (532) 151 (563) 90 (563) 90

Other ..................... 10,121 3,371 9,623 2,658 8,490 2,171

-------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --------

Operating Earnings .......... 82,043 41,102 72,410 27,742 68,195 31,497

Sales of securities and

unusual sales of assets .. 67,260 36,651 65,089 21,875 45,298 14,877

-------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --------

Total Earnings .............. $149,303 $ 77,753 $137,499 $ 49,617 $113,493 $ 46,374

======== ======== ======== ======== ======== ========

(1) October through December

(2) 1982 and 1983 are not comparable; major assets were

transferred in the merger.

For a discussion of the businesses owned by Wesco, please

read Charlie Munger’s report on pages 46-51. Charlie replaced

Louie Vincenti as Chairman of Wesco late in 1983 when health

forced Louie’s retirement at age 77. In some instances, “health”

is a euphemism, but in Louie’s case nothing but health would

cause us to consider his retirement. Louie is a marvelous man

and has been a marvelous manager.

The special GEICO distribution reported in the table arose

when that company made a tender offer for a portion of its stock,

�

buying both from us and other shareholders. At GEICO’s request,

we tendered a quantity of shares that kept our ownership

percentage the same after the transaction as before. The

proportional nature of our sale permitted us to treat the

proceeds as a dividend. Unlike individuals, corporations net

considerably more when earnings are derived from dividends rather

than from capital gains, since the effective Federal income tax

rate on dividends is 6.9% versus 28% on capital gains.

Even with this special item added in, our total dividends

from GEICO in 1983 were considerably less than our share of

GEICO’s earnings. Thus it is perfectly appropriate, from both an

accounting and economic standpoint, to include the redemption

proceeds in our reported earnings. It is because the item is

large and unusual that we call your attention to it.

The table showing you our sources of earnings includes

dividends from those non-controlled companies whose marketable

equity securities we own. But the table does not include

earnings those companies have retained that are applicable to our

ownership. In aggregate and over time we expect those

undistributed earnings to be reflected in market prices and to

increase our intrinsic business value on a dollar-for-dollar

basis, just as if those earnings had been under our control and

reported as part of our profits. That does not mean we expect

all of our holdings to behave uniformly; some will disappoint us,

others will deliver pleasant surprises. To date our experience

has been better than we originally anticipated, In aggregate, we

have received far more than a dollar of market value gain for

every dollar of earnings retained.

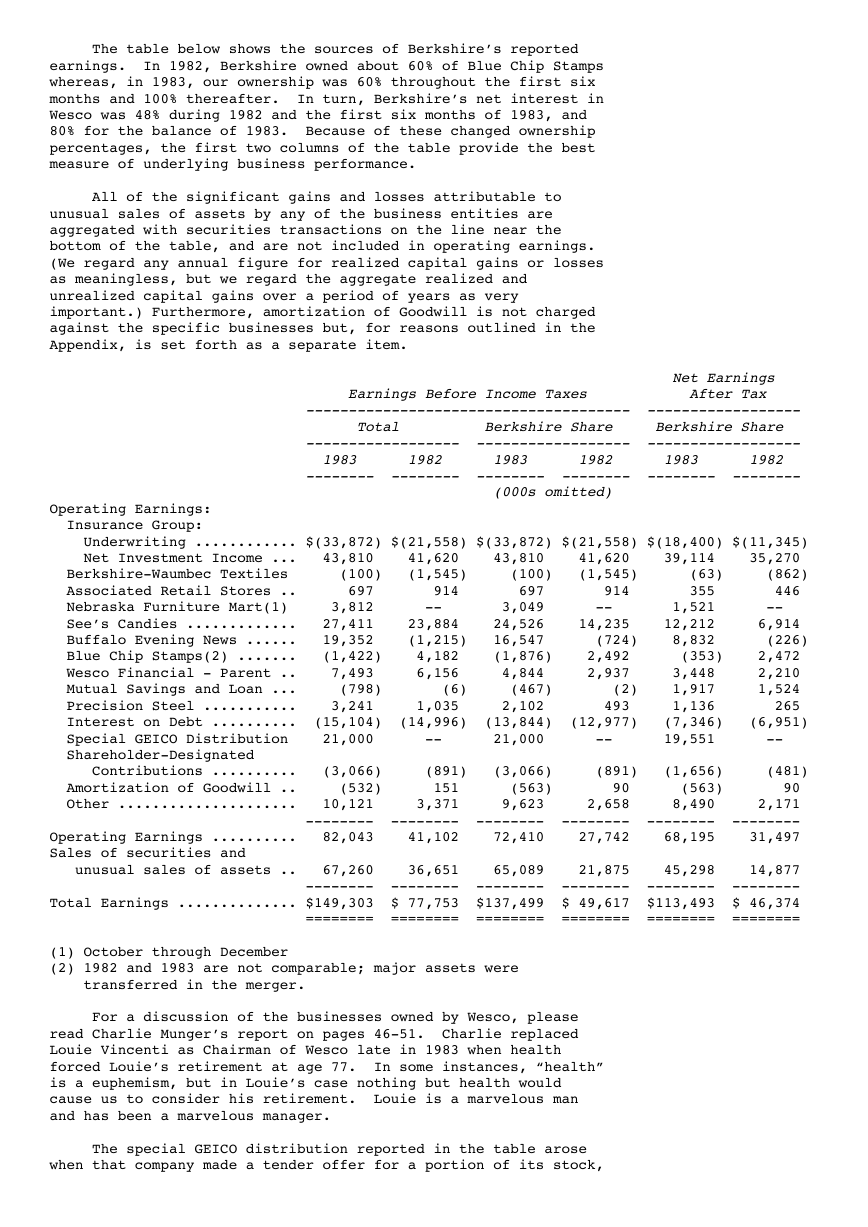

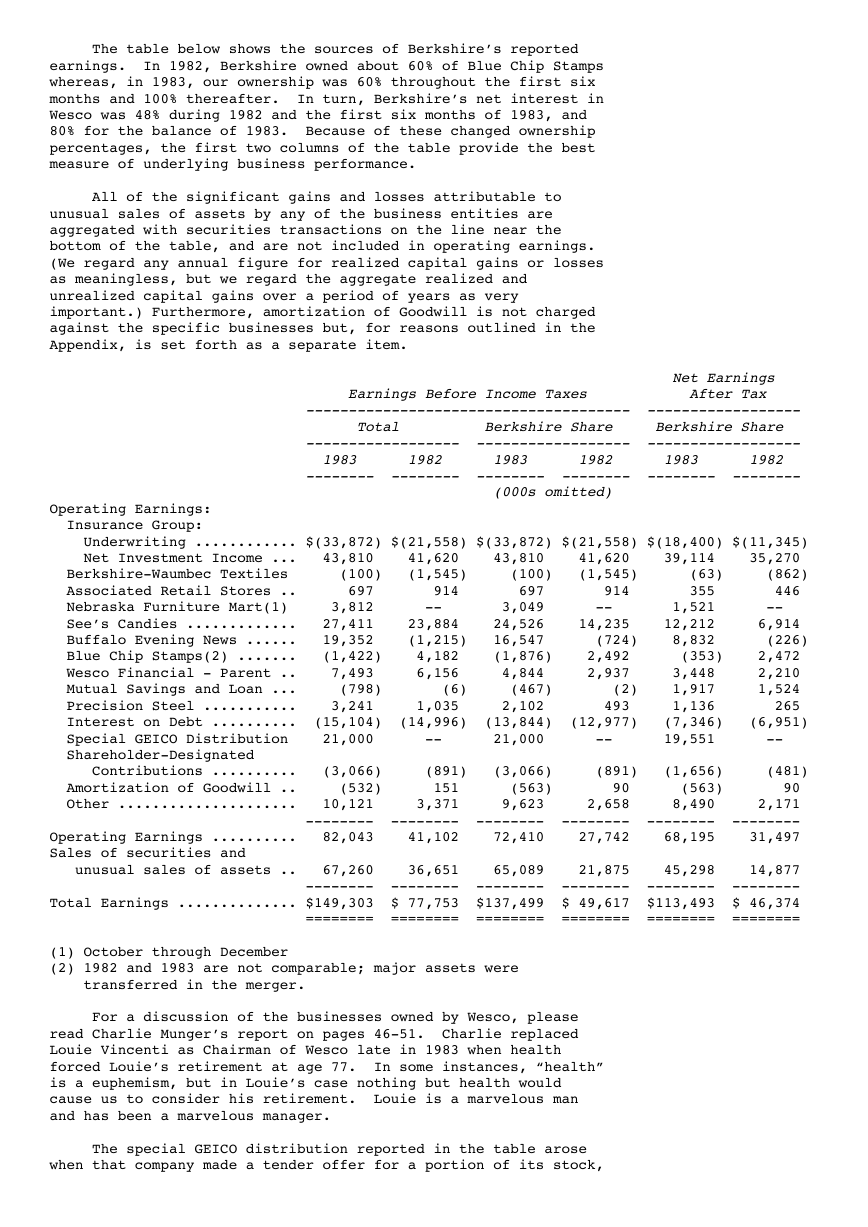

The following table shows our 1983 yearend net holdings in

marketable equities. All numbers represent 100% of Berkshire’s

holdings, and 80% of Wesco’s holdings. The portion attributable

to minority shareholders of Wesco has been excluded.

No. of Shares Cost Market

------------- ---------- ----------

(000s omitted)

690,975 Affiliated Publications, Inc. .... $ 3,516 $ 26,603

4,451,544 General Foods Corporation(a) ..... 163,786 228,698

6,850,000 GEICO Corporation ................ 47,138 398,156

2,379,200 Handy & Harman ................... 27,318 42,231

636,310 Interpublic Group of Companies, Inc. 4,056 33,088

197,200 Media General .................... 3,191 11,191

250,400 Ogilvy & Mather International .... 2,580 12,833

5,618,661 R. J. Reynolds Industries, Inc.(a) 268,918 341,334

901,788 Time, Inc. ....................... 27,732 56,860

1,868,600 The Washington Post Company ...... 10,628 136,875

---------- ----------

$558,863 $1,287,869

All Other Common Stockholdings ... 7,485 18,044

---------- ----------

Total Common Stocks .............. $566,348 $1,305,913

========== ==========

(a) WESCO owns shares in these companies.

Based upon present holdings and present dividend rates -

excluding any special items such as the GEICO proportional

redemption last year - we would expect reported dividends from

this group to be approximately $39 million in 1984. We can also

make a very rough guess about the earnings this group will retain

that will be attributable to our ownership: these may total about

$65 million for the year. These retained earnings could well

have no immediate effect on market prices of the securities.

Over time, however, we feel they will have real meaning.

In addition to the figures already supplied, information

�

regarding the businesses we control appears in Management’s

Discussion on pages 40-44. The most significant of these are

Buffalo Evening News, See’s, and the Insurance Group, to which we

will give some special attention here.

Buffalo Evening News

First, a clarification: our corporate name is Buffalo

Evening News, Inc. but the name of the newspaper, since we began

a morning edition a little over a year ago, is Buffalo News.

In 1983 the News somewhat exceeded its targeted profit

margin of 10% after tax. Two factors were responsible: (1) a

state income tax cost that was subnormal because of a large loss

carry-forward, now fully utilized, and (2) a large drop in the

per-ton cost of newsprint (an unanticipated fluke that will be

reversed in 1984).

Although our profit margins in 1983 were about average for

newspapers such as the News, the paper’s performance,

nevertheless, was a significant achievement considering the

economic and retailing environment in Buffalo.

Buffalo has a concentration of heavy industry, a segment of

the economy that was hit particularly hard by the recent

recession and that has lagged the recovery. As Buffalo consumers

have suffered, so also have the paper’s retailing customers.

Their numbers have shrunk over the past few years and many of

those surviving have cut their linage.

Within this environment the News has one exceptional

strength: its acceptance by the public, a matter measured by the

paper’s “penetration ratio” - the percentage of households within

the community purchasing the paper each day. Our ratio is

superb: for the six months ended September 30, 1983 the News

stood number one in weekday penetration among the 100 largest

papers in the United States (the ranking is based on “city zone”

numbers compiled by the Audit Bureau of Circulations).

In interpreting the standings, it is important to note that

many large cities have two papers, and that in such cases the

penetration of either paper is necessarily lower than if there

were a single paper, as in Buffalo. Nevertheless, the list of

the 100 largest papers includes many that have a city to

themselves. Among these, the News is at the top nationally, far

ahead of many of the country’s best-known dailies.

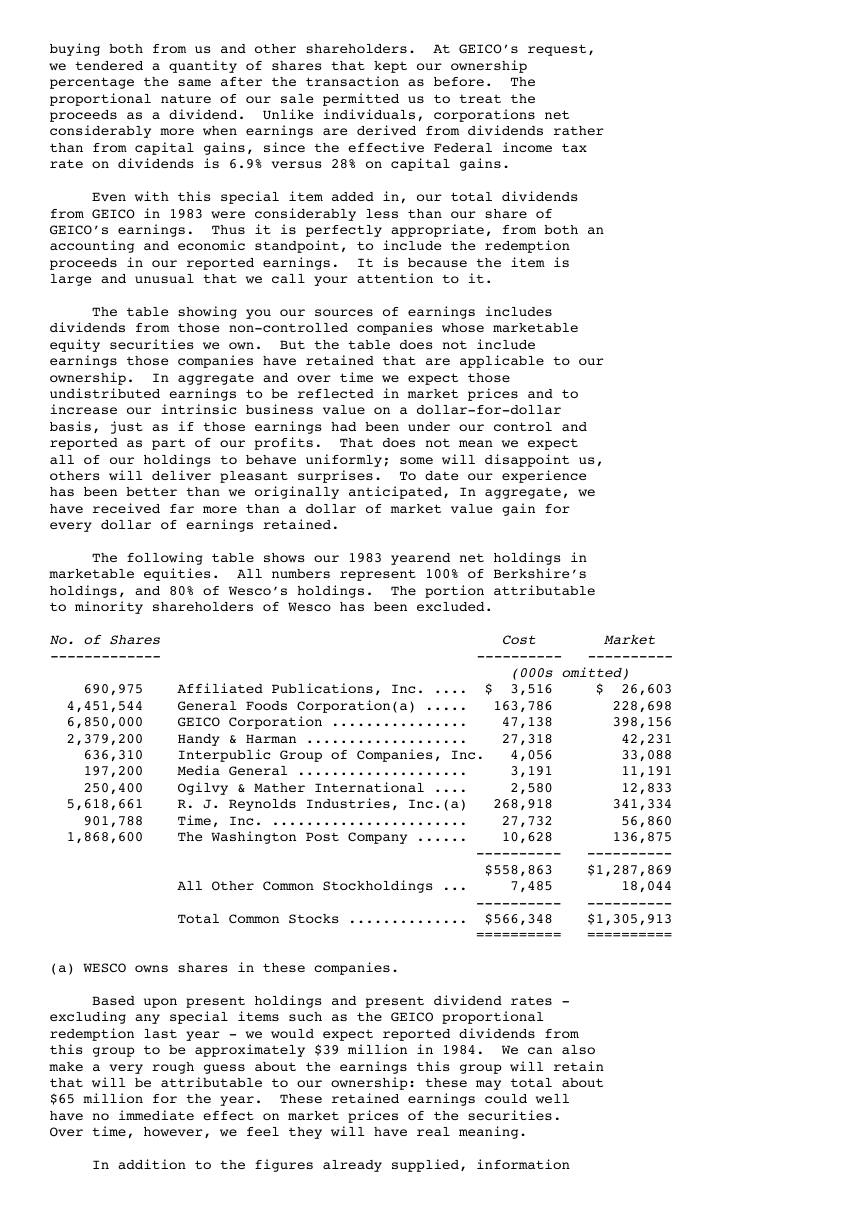

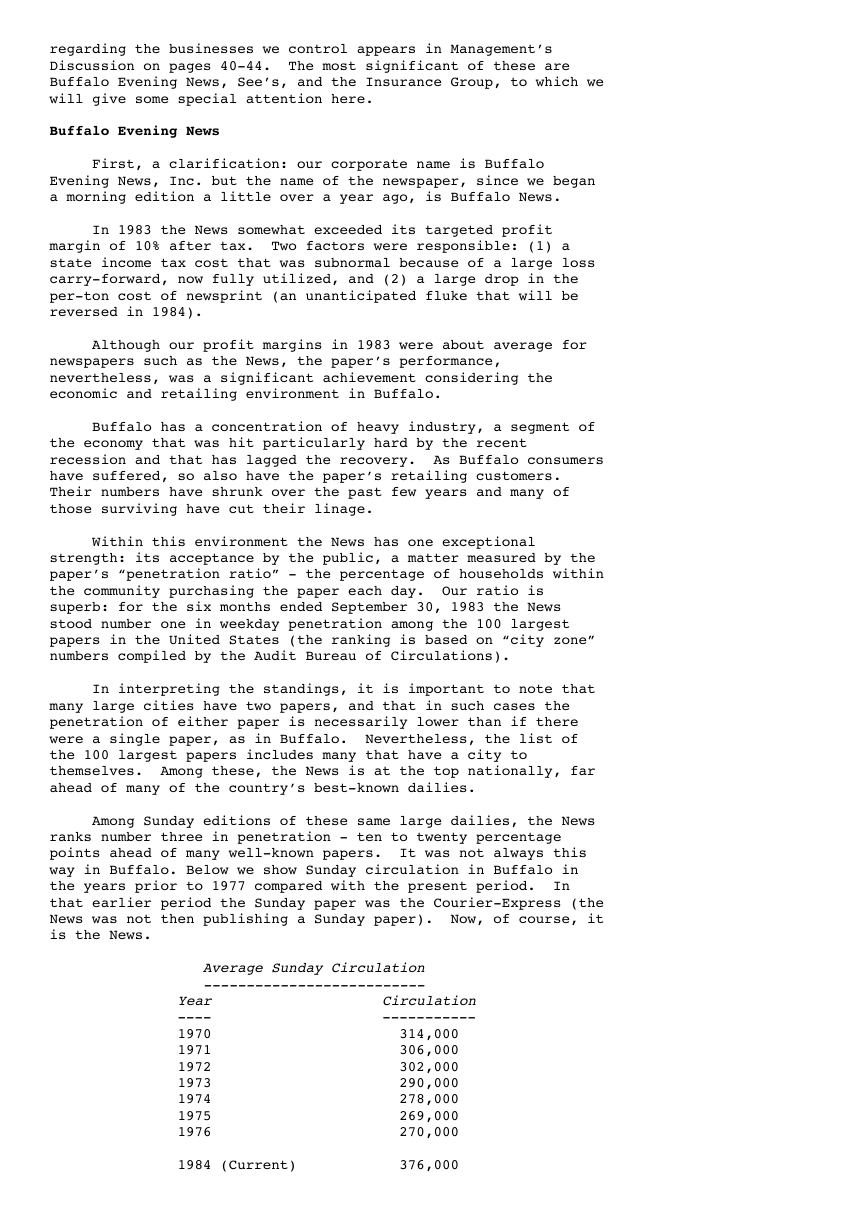

Among Sunday editions of these same large dailies, the News

ranks number three in penetration - ten to twenty percentage

points ahead of many well-known papers. It was not always this

way in Buffalo. Below we show Sunday circulation in Buffalo in

the years prior to 1977 compared with the present period. In

that earlier period the Sunday paper was the Courier-Express (the

News was not then publishing a Sunday paper). Now, of course, it

is the News.

Average Sunday Circulation

--------------------------

Year Circulation

---- -----------

1970 314,000

1971 306,000

1972 302,000

1973 290,000

1974 278,000

1975 269,000

1976 270,000

1984 (Current) 376,000

�