i

�

The Data Warehouse Lifecycle Toolkit

Table of Contents

- The Chess Pieces

- Introducing Data Warehouse Architecture

- Back Room Technical Architecture

- The Business Dimensional Lifecycle

- Project Planning and Management

- Collecting the Requirements

- A First Course on Dimensional Modeling

- A Graduate Course on Dimensional Modeling

- Building Dimensional Models

Chapter 1

Section 1 - Project Management and Requirements

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Section 2 - Data Design

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Section 3 - Architecture

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10 - Architecture for the Front Room

Chapter 11 - Infrastructure and Metadata

Chapter 12 - A Graduate Course on the Internet and Security

Chapter 13 - Creating the Architecture Plan and Selecting Products

Section 4 – Implementation

Chapter 14 - A Graduate Course on Aggregates

Chapter 15 - Completing the Physical Design

Chapter 16 - Data Staging

Chapter 17 - Building End User Applications

Section 5 - Deployment and Growth

Chapter 18 - Planning the Deployment

Chapter 19 - Maintaining and Growing the Data Warehouse

ii

�

The Purpose of Each Chapter

1.

The Chess Pieces. As of the writing of this book, a lot of vague terminology was

being tossed around in the data warehouse marketplace. Even the term data

warehouse has lost its precision. Some people are even trying to define the data

warehouse as a nonqueryable data resource! We are not foolish enough to think we

can settle all the terminology disputes in these pages, but within this book we will

stick to a very specific set of meanings. This chapter briefly defines all the important

terms used in data warehousing in a consistent way. Perhaps this is something like

studying all the chess pieces and what they can do before attempting to play a chess

game. We think we are pretty close to the mainstream with these definitions.

Section 1: Project Management and Requirements

2.

The Business Dimensional Lifecycle. We define

the complete Business

Dimensional Lifecycle from 50,000 feet. We briefly discuss each step and give

perspective on the lifecycle as a whole.

Project Planning and Management. In this chapter, we define the project and talk

about setting its scope within your environment. We talk extensively about the

various project roles and responsibilities. You won’t necessarily need a full headcount

equivalent for each of these roles, but you will need to fill them in almost any

imaginable project. This is a chapter for managers.

Collecting the Requirements. Collecting the business and data requirements is the

foundation of the entire data warehouse effort—or at least it should be. Collecting the

requirements is an art form, and it is one of the least natural activities for an IS

organization. We give you techniques to make this job easier and hope to impress

upon you the necessity of spending quality time on this step.

Section 2: Data Design

5.

A First Course on Dimensional Modeling. We start with an energetic argument for

the value of dimensional modeling. We want you to understand the depth of our

commitment to this approach. After performing hundreds of data warehouse designs

and installations over the last 15 years, we think this is the only approach you can

use to achieve the twin goals of understandability and performance. We then reveal

the central secret for combining multiple dimensional models together into a coherent

whole. This secret is called conformed dimensions and conformed facts. We call this

approach the Data Warehouse Bus Architecture. Your computer has a backbone,

called the computer bus, that everything connects to, and your data warehouse has a

backbone, called the data warehouse bus, that everything connects to. The

remainder of this chapter is a self-contained introduction to the science of

dimensional modeling for data warehouses. This introduction can be viewed as an

appendix to the full treatment of this subject in Ralph Kimball’s earlier book, The Data

Warehouse Toolkit.

6.

A Graduate Course on Dimensional Modeling. Here we collect all the hardest

dimensional modeling situations we can think of. Most of these examples come from

specific business situations, such as dealing with a monster customer list.

7.

Building Dimensional Models. In this chapter we tackle the issue of how to create

the right model within your organization. You start with a matrix of data marts and

dimensions, and then you design each fact table in each data mart according to the

techniques described in Chapter 5. The last half of this chapter describes the real-life

management issues in applying this methodology and building all the dimensional

models needed in each data mart.

3.

4.

Section 3: Architecture

8.

Introducing Data Warehouse Architecture. In this chapter we introduce all the

components of the technical architecture at a medium level of detail. This paints the

overall picture. The remaining five chapters in this section go into the specific areas

of detail. We divide the discussion into data architecture, application architecture, and

infrastructure. If you follow the Data Warehouse Bus Architecture we developed in

Chapter 5, you will be able to develop your data marts one at a time, and you will end

iii

�

up with a flexible, coherent overall data warehouse. But we didn’t say it would be

easy.

9.

Technical Back Room Architecture. We introduce you to the system components

in the back room: the source systems, the reporting instance, the data staging area,

the base level data warehouse, and the business process data marts. We tell you

what happened to the operational data store (ODS). We also talk about all the

services you must provide in the back room to get the data ready to load into your

data mart presentation server.

10.

Architecture for the Front Room. The front room is your publishing operation. You

make the data available and provide an array of tools for different user needs. We

give you a comprehensive view of the many requirements you must support in the

front room.

11.

Infrastructure and Metadata. Infrastructure is the glue that holds the data

warehouse together. This chapter covers the nuts and bolts. We deal with the detail

we think every data warehouse designer and manager need to know about

hardware, software, communications, and especially metadata.

12.

A Graduate Course on the Internet and Security. The Internet has a potentially

huge impact on the life of the data warehouse manager, but many data warehouse

managers are either not aware of the true impact of the Internet or they are avoiding

the issues. This chapter will expose you to the current state of the art on Internet-

based data warehouses and security issues and give you a list of immediate actions

to take to protect your installation. The examples throughout this chapter are slanted

toward the exposures and challenges faced by the data warehouse owner.

13.

Creating the Architecture Plan and Selecting Products. Now that you are a

software, hardware, and infrastructure expert, you are ready to commit to a specific

architecture plan for your organization and to choose specific products. We talk about

the selection process and which combination of product categories you need. Bear in

mind this book is not a platform for talking about specific vendors, however.

Section 4: Implementation

14.

A Graduate Course on Aggregations. Aggregations are prestored summaries that

you create to boost performance of your database systems. This chapter dives

deeply into the structure of aggregations, where you put them, how you use them,

and how you administer them. Aggregations are the single most cost-effective way to

boost performance in a large data warehouse system assuming that the rest of your

system is constructed according to the Data Warehouse Bus Architecture.

15.

Completing the Physical Design. Although we don’t know which DBMS and which

hardware architecture you will choose, there are a number of powerful ideas at this

level that you should understand. We talk about physical data structures, indexing

strategies, specialty databases for data warehousing, and RAID storage strategies.

16.

Data Staging. Once you have the major systems in place, the biggest and riskiest

step in the process is getting the data out of the legacy systems and loading into the

data mart DBMSs. The data staging area is the intermediate place where you bring

the legacy data in for cleaning and transforming. We have a lot of strong opinions

about what should and should not happen in the data staging area.

17.

Building End User Applications. After the data is finally loaded into the DBMS, we

still have to arrange for a soft landing on the users’ desktops. The end user

applications are all the query tools and report writers and data mining systems for

getting the data out of the DBMS and doing something useful. This chapter describes

the starter set of end user applications you need to provide as part of the initial data

mart implementation.

Section 5: Deployment and Growth

18.

Planning the Deployment. When everything is ready to go, you still have to roll the

system out and behave in many ways like a commercial software vendor. You need

to install the software, train the users, collect bug reports, solicit feedback, and

respond to new requirements. You need to plan carefully so that you can deliver

according to the expectations you have set.

iv

�

19.

Maintaining and Growing the Data Warehouse. Finally, when your entire data

mart edifice is up and running, you have to turn around to do it again! As we said

earlier, the data warehouse is more of a process than a project. This chapter is an

appropriate end for the book, if only because it leaves you with a valuable last

impression: You are never done.

Supporting Tools

•

Appendix A. This appendix summarizes the entire project plan for the Business

Dimensional Lifecycle in one place and in one format. All of the project tasks and roles

are listed.

•

Appendix B. This appendix is a guided tour of the contents of the CD-ROM. All of the

useful checklists, templates, and forms are listed. We also walk you through how to use

our sample design of a Data Warehouse Bus Architecture.

•

CD-ROM. The CD-ROM that accompanies the book contains a large number of actual

checklists, templates, and forms for you to use with your data warehouse development. It

also includes a sample design illustrating the Data Warehouse Bus Architecture

The Goals of a Data Warehouse

One of the most important assets of an organization is its information. This asset is

almost always kept by an organization in two forms: the operational systems of record

and the data warehouse. Crudely speaking, the operational systems of record are where

the data is put in, and the data warehouse is where we get the data out. In The Data

Warehouse Toolkit, we described this dichotomy at length. At the time of this writing, it is

no longer so necessary to convince the world that there are really two systems or that

there will always be two systems. It is now widely recognized that the data warehouse

has profoundly different needs, clients, structures, and rhythms than the operational

systems of record.

Ultimately, we need to put aside the details of implementation and modeling, and

remember what the fundamental goals of the data warehouse are. In our opinion, the

data warehouse:

•

•

•

Makes an organization’s information accessible. The contents of the data

warehouse are understandable and navigable, and the access is characterized by fast

performance. These requirements have no boundaries and no

limits.

Understandable means correctly labeled and obvious. Navigable means recognizing

your destination on the screen and getting there in one click. Fast performance means

zero wait time. Anything else is a compromise and therefore something that we must

improve.

fixed

Makes the organization’s information consistent. Information from one part of the

organization can be matched with information from another part of the organization. If

two measures of an organization have the same name, then they must mean the same

thing. Conversely, if two measures don’t mean the same thing, then they are labeled

differently. Consistent information means high-quality information. It means that all of

the information is accounted for and is complete. Anything else is a compromise and

therefore something that we must improve.

Is an adaptive and resilient source of information. The data warehouse is designed

for continuous change. When new questions are asked of the data warehouse, the

existing data and the technologies are not changed or disrupted. When new data is

added to the data warehouse, the existing data and the technologies are not changed

or disrupted. The design of the separate data marts that make up the data warehouse

must be distributed and incremental. Anything else is a compromise and therefore

something that we must improve.

•

Is a secure bastion that protects our information asset. The data warehouse not

only controls access to the data effectively, but gives its owners great visibility into the

uses and abuses of that data, even after it has left the data warehouse. Anything else

is a compromise and therefore something that we must improve.

v

�

•

Is the foundation for decision making. The data warehouse has the right data in it to

support decision making. There is only one true output from a data warehouse: the

decisions that are made after the data warehouse has presented its evidence. The

original label that predates the data warehouse is still the best description of what we are

trying to build: a decision support system.

The Goals of This Book

If we succeed with this book, you—the designers and managers of large data

warehouses—will achieve your goals more quickly. You will build effective data

warehouses that match well against the goals outlined in the preceding section, and you

will make fewer mistakes along the way. Hopefully, you will not reinvent the wheel and

discover “previously owned” truths.

We have tried to be as technical as this large subject allows, without getting waylaid by

vendor-specific details. Certainly, one of the interesting aspects of working in the data

warehouse marketplace is the breadth of knowledge needed to understand all of the data

warehouse responsibilities. We feel quite strongly that this wide perspective must be

maintained because of the continuously evolving nature of data warehousing. Even if

data warehousing leaves behind such bedrock notions as text and number data, or the

reliance on relational database technology, most of the principles of this book would

remain applicable, because the mission of a data warehouse team is to build a decision

support system in the most fundamental sense of the words.

We think that a moderate amount of structure and discipline helps a lot in building a large

and complex data warehouse. We want to transfer this structure and discipline to you

through this book. We want you to understand and anticipate the whole Business

Dimensional Lifecycle, and we want you to infuse your own organizations with this

perspective. In many ways, the data warehouse is an expression of information systems’

fundamental charter: to collect the organization’s information and make it useful.

The idea of a lifecycle suggests an endless process where data warehouses sprout and

flourish and eventually die, only to be replaced with new data warehouses that build on the

legacies of the previous generations. This book tries to capture that perspective and help

you get it started in your organization.

Visit the Companion Web Site

This book is necessarily a static snapshot of the data warehouse industry and the

methodologies we think are important. For a dynamic, up-to-date perspective on these

issues, please visit this book’s Web site at www.wiley.com/compbooks/kimball, or log on to

the mirror site at www.lifecycle-toolkit.com. We, the authors of this book, intend to maintain

this Web site personally and make it a useful resource for data warehouse professionals.

vi

�

1. 1

�

Overview

All of the authors of this book worked together at Metaphor Computer Systems over a

period that spanned more than ten years, from 1982 to 1994. Although the real value of

the Metaphor experience was the building of hundreds of data warehouses, there was an

ancillary benefit that we sometimes find useful. We are really conscious of metaphors.

How could we avoid metaphors, with a name like that?

A useful metaphor to get this book started is to think about studying the chess pieces

very carefully before trying to play the game of chess. You really need to learn the

shapes of the pieces and what they can do on the board. More subtly, you need to learn

the strategic significance of the pieces and how to wield them in order to win the game.

Certainly, with a data warehouse, as well as with chess, you need to think way ahead.

Your opponent is the ever-changing nature of the environment you are forced to work in.

You can’t avoid the changing user needs, the changing business conditions, the

changing nature of the data you are given to work with, and the changing technical

environment. So maybe the game of data warehousing is something like the game of

chess. At least it’s a pretty good metaphor.

If you intend to read this book, you need to read this chapter. We are fairly precise in this

book with our vocabulary, and you will get more out of this book if you know where we

stand. We begin by briefly defining the basic elements of the data warehouse. As we

remarked in the introduction, there is not universal agreement in the marketplace over

these definitions. But our use of these words is as close to mainstream practice as we

can make them. Here in this book, we will use these words precisely and consistently,

according to the definitions we provide in the next section.

We will then list the data warehouse processes you need to be concerned about. This list is

a declaration of the boundaries for your job. Perhaps the biggest insight into your

responsibilities as a data warehouse manager is that this list of data warehouse processes

is long and somewhat daunting

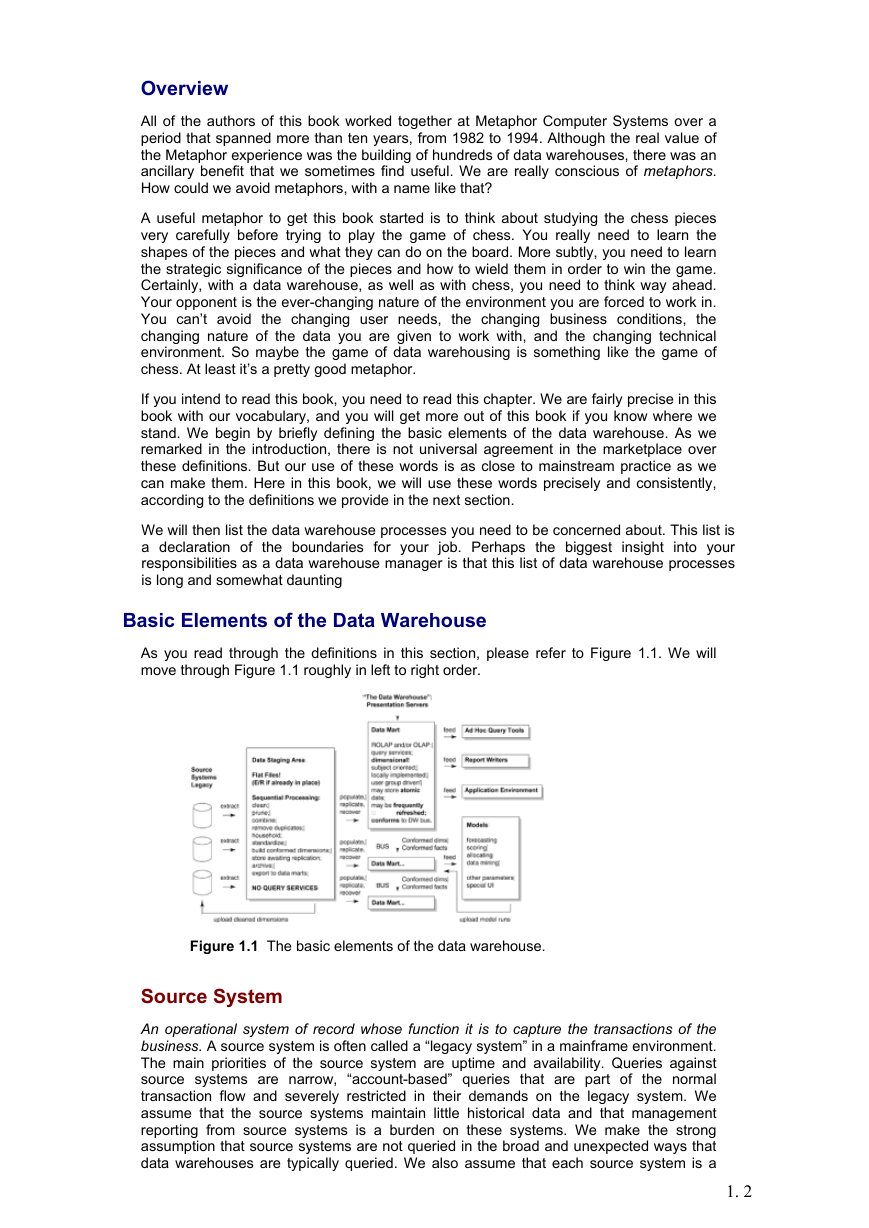

Basic Elements of the Data Warehouse

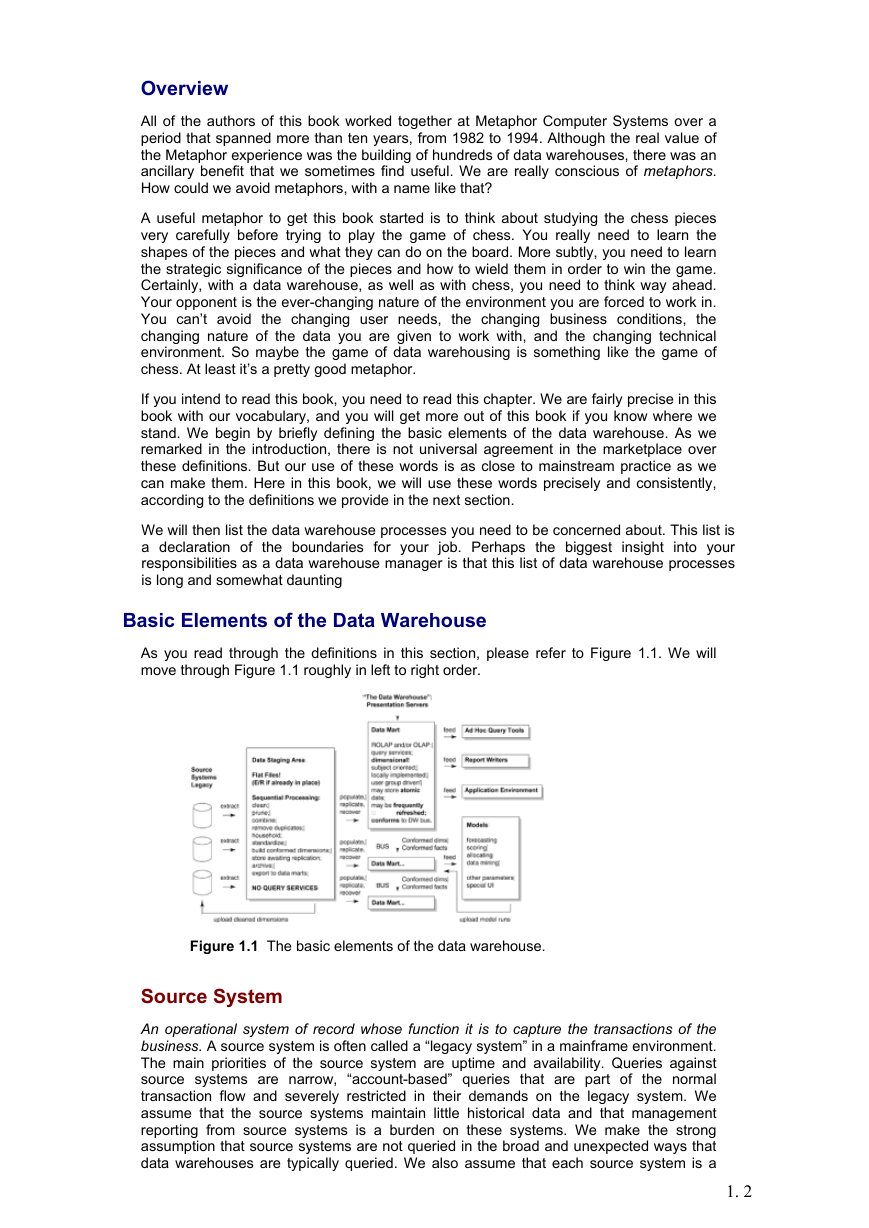

As you read through the definitions in this section, please refer to Figure 1.1. We will

move through Figure 1.1 roughly in left to right order.

Figure 1.1 The basic elements of the data warehouse.

Source System

An operational system of record whose function it is to capture the transactions of the

business. A source system is often called a “legacy system” in a mainframe environment.

The main priorities of the source system are uptime and availability. Queries against

source systems are narrow, “account-based” queries that are part of the normal

transaction flow and severely restricted in their demands on the legacy system. We

assume that the source systems maintain little historical data and that management

reporting from source systems is a burden on these systems. We make the strong

assumption that source systems are not queried in the broad and unexpected ways that

data warehouses are typically queried. We also assume that each source system is a

1. 2

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc