HBR.ORG

NOVEMBER 2014

REPRINT R1411C

SPOTLIGHT ON MANAGING THE INTERNET OF THINGS

How Smart,

Connected Products

Are Transforming

Competition

by Michael E. Porter and James E. Heppelmann

This HBR article is made available to you with compliments of PTC Inc. Further posting, copying or distributing is copyright infringement.

�

SPOTLIGHT ON MANAGING THE INTERNET OF THINGS

SPOTLIGHT

ARTWORK Chris Labrooy

Braun, Toaster

This HBR article is made available to you with compliments of PTC Inc. Further posting, copying or distributing is copyright infringement.

�

FOR ARTICLE REPRINTS CALL 800-988-0886 OR 617-783-7500, OR VISIT HBR.ORG

Michael E. Porter is the

Bishop William Lawrence

University Professor, based

at Harvard Business School.

James E. Heppelmann

is the president and CEO

of PTC, a Massachusetts-

based software company

that helps manufacturers

create, operate, and

service products.

How Smart,

Connected Products

Are Transforming

Competition

by Michael E. Porter and James E. Heppelmann

This HBR article is made available to you with compliments of PTC Inc. Further posting, copying or distributing is copyright infringement.

November 2014 Harvard Business Review 3

�

SPOTLIGHT ON MANAGING THE INTERNET OF THINGS

I

nformation technology is revolutionizing

products. Once composed solely of mechanical

and electrical parts, products have become

complex systems that combine hardware,

sensors, data storage, microprocessors,

software, and connectivity in myriad ways.

These “smart, connected products”—made

possible by vast improvements in processing power and device

miniaturization and by the network benefits of ubiquitous wireless

connectivity—have unleashed a new era of competition.

Smart, connected products offer exponentially

expanding opportunities for new functionality, far

greater reliability, much higher product utilization,

and capabilities that cut across and transcend tra-

ditional product boundaries. The changing nature

of products is also disrupting value chains, forcing

companies to rethink and retool nearly everything

they do internally.

These new types of products alter industry struc-

ture and the nature of competition, exposing com-

panies to new competitive opportunities and threats.

They are reshaping industry boundaries and creating

entirely new industries. In many companies, smart,

connected products will force the fundamental

question, “What business am I in?”

Smart, connected products raise a new set of stra-

tegic choices related to how value is created and cap-

tured, how the prodigious amount of new (and sensi-

tive) data they generate is utilized and managed, how

relationships with traditional business partners such

as channels are redefined, and what role companies

should play as industry boundaries are expanded.

The phrase “internet of things” has arisen to

reflect the growing number of smart, connected

products and highlight the new opportunities they

can represent. Yet this phrase is not very helpful in

understanding the phenomenon or its implications.

The internet, whether involving people or things, is

simply a mechanism for transmitting information.

What makes smart, connected products fundamen-

tally different is not the internet, but the changing

nature of the “things.” It is the expanded capabilities

of smart, connected products and the data they gen-

erate that are ushering in a new era of competition.

Companies must look beyond the technologies

themselves to the competitive transformation tak-

ing place. This article, and a companion piece to be

published soon in HBR, will deconstruct the smart,

connected products revolution and explore its stra-

tegic and operational implications.

The Third Wave of IT-Driven

Competition

Twice before over the past 50 years, information

technology radically reshaped competition and

strategy; we now stand at the brink of a third trans-

formation. Before the advent of modern information

technology, products were mechanical and activities

in the value chain were performed using manual, pa-

per processes and verbal communication. The first

wave of IT, during the 1960s and 1970s, automated

individual activities in the value chain, from order

processing and bill paying to computer-aided design

and manufacturing resource planning. (See “How

Information Gives You Competitive Advantage,” by

Michael Porter and Victor Millar, HBR, July 1985.)

The productivity of activities dramatically increased,

in part because huge amounts of new data could be

captured and analyzed in each activity. This led to

the standardization of processes across companies—

and raised a dilemma for companies about how to

capture IT’s operational benefits while maintaining

distinctive strategies.

The rise of the internet, with its inexpensive and

ubiquitous connectivity, unleashed the second wave

of IT-driven transformation, in the 1980s and 1990s

(see Michael Porter’s “Strategy and the Internet,”

HBR, March 2001). This enabled coordination and

INSIGHT CENTER Find

our monthlong series of

articles on the internet

of things at hbr.org/

insights/iot.

4 Harvard Business Review November 2014

This HBR article is made available to you with compliments of PTC Inc. Further posting, copying or distributing is copyright infringement.

COPYRIGHT © 2014 HARVARD BUSINESS SCHOOL PUBLISHING CORPORATION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

�

FOR ARTICLE REPRINTS CALL 800-988-0886 OR 617-783-7500, OR VISIT HBR.ORG

Idea in Brief

A CHANGING ENVIRONMENT

Smart, connected products

offer exponentially expanding

opportunities for new

functionality and capabilities

that transcend traditional

product boundaries.

The changing nature of

products is disrupting value

chains and forcing companies

to rethink nearly everything

they do, from how they

conceive, design, and

source products; to how

they manufacture, operate,

and service them; to how

they build and secure the

necessary IT infrastructure.

THE NEW STRATEGIC CHOICES

Smart, connected products

raise a new set of strategic

choices about how value

is created and captured,

how companies work with

traditional and new partners,

and how they secure

competitive advantage as

the new capabilities reshape

industry boundaries. For

many firms, smart, connected

products will force the

fundamental question,

“What business am I in?”

This article provides a

framework for developing

strategy and achieving

competitive advantage

in a smart, connected world.

integration across individual activities; with out-

side suppliers, channels, and customers; and across

geography. It allowed firms, for example, to closely

integrate globally distributed supply chains.

The first two waves gave rise to huge productiv-

ity gains and growth across the economy. While the

value chain was transformed, however, products

themselves were largely unaffected.

Now, in the third wave, IT is becoming an integral

part of the product itself. Embedded sensors, proces-

sors, software, and connectivity in products (in effect,

computers are being put inside products), coupled

with a product cloud in which product data is stored

and analyzed and some applications are run, are driv-

ing dramatic improvements in product functionality

and performance. Massive amounts of new product-

usage data enable many of those improvements.

Another leap in productivity in the economy will

be unleashed by these new and better products. In

addition, producing them will reshape the value

chain yet again, by changing product design, market-

ing, manufacturing, and after-sale service and by cre-

ating the need for new activities such as product data

analytics and security. This will drive yet another

wave of value-chain-based productivity improve-

ment. The third wave of IT-driven transformation

thus has the potential to be the biggest yet, triggering

even more innovation, productivity gains, and eco-

nomic growth than the previous two.

Some have suggested that the internet of things

“changes everything,” but that is a dangerous over-

simplification. As with the internet itself, smart, con-

nected products reflect a whole new set of techno-

logical possibilities that have emerged. But the rules

of competition and competitive advantage remain

the same. Navigating the world of smart, connected

products requires that companies understand these

rules better than ever.

What Are Smart,

Connected Products?

Smart, connected products have three core ele-

ments: physical components, “smart” components,

and connectivity components. Smart components

amplify the capabilities and value of the physical

components, while connectivity amplifies the ca-

pabilities and value of the smart components and

enables some of them to exist outside the physical

product itself. The result is a virtuous cycle of value

improvement.

Physical components comprise the product’s

mechanical and electrical parts. In a car, for example,

these include the engine block, tires, and batteries.

Smart components comprise the sensors, mi-

croprocessors, data storage, controls, software, and,

typically, an embedded operating system and en-

hanced user interface. In a car, for example, smart

components include the engine control unit, anti-

lock braking system, rain-sensing windshields with

automated wipers, and touch screen displays. In

many products, software replaces some hardware

components or enables a single physical device to

perform at a variety of levels.

Connectivity components comprise the ports,

antennae, and protocols enabling wired or wireless

connections with the product. Connectivity takes

three forms, which can be present together:

• One-to-one: An individual product connects to

the user, the manufacturer, or another product

through a port or other interface—for example,

when a car is hooked up to a diagnostic machine.

• One-to-many: A central system is continuously or

intermittently connected to many products simul-

taneously. For example, many Tesla automobiles

are connected to a single manufacturer system

that monitors performance and accomplishes re-

mote service and upgrades.

This HBR article is made available to you with compliments of PTC Inc. Further posting, copying or distributing is copyright infringement.

November 2014 Harvard Business Review 5

�

SPOTLIGHT ON MANAGING THE INTERNET OF THINGS

• Many-to-many: Multiple products connect to

many other types of products and often also to

external data sources. An array of types of farm

equipment are connected to one another, and to

geolocation data, to coordinate and optimize the

farm system. For example, automated tillers inject

nitrogen fertilizer at precise depths and intervals,

and seeders follow, placing corn seeds directly in

the fertilized soil.

Some have suggested that the

internet of things “changes

everything,” but that is a

dangerous oversimplification.

The rules of competition and

competitive advantage still apply.

Connectivity serves a dual purpose. First, it al-

lows information to be exchanged between the

product and its operating environment, its maker, its

users, and other products and systems. Second, con-

nectivity enables some functions of the product to

exist outside the physical device, in what is known

as the product cloud. For example, in Bose’s new

Wi-Fi system, a smartphone application running in

the product cloud streams music to the system from

the internet. To achieve high levels of functionality,

all three types of connectivity are necessary.

Smart, connected products are emerging across

all manufacturing sectors. In heavy machinery,

Schindler’s PORT Technology reduces elevator

wait times by as much as 50% by predicting eleva-

tor demand patterns, calculating the fastest time to

destination, and assigning the appropriate elevator

to move passengers quickly. In the energy sector,

ABB’s smart grid technology enables utilities to ana-

lyze huge amounts of real-time data across a wide

range of generating, transforming, and distribution

equipment (manufactured by ABB as well as others),

such as changes in the temperature of transformers

and secondary substations. This alerts utility control

centers to possible overload conditions, allowing

This technology enables not only rapid product

application development and operation but the col-

lection, analysis, and sharing of the potentially huge

amounts of longitudinal data generated inside and

outside the products that has never been available

before. Building and supporting the technology

stack for smart, connected products requires sub-

stantial investment and a range of new skills—such

6 Harvard Business Review November 2014

This HBR article is made available to you with compliments of PTC Inc. Further posting, copying or distributing is copyright infringement.

adjustments that can prevent blackouts before they

occur. In consumer goods, Big Ass ceiling fans sense

and engage automatically when a person enters a

room, regulate speed on the basis of temperature

and humidity, and recognize individual user prefer-

ences and adjust accordingly.

Why now? An array of innovations across the

technology landscape have converged to make

smart, connected products technically and eco-

nomically feasible. These include breakthroughs

in the performance, miniaturization, and energy

efficiency of sensors and batteries; highly compact,

low-cost computer processing power and data stor-

age, which make it feasible to put computers inside

products; cheap connectivity ports and ubiquitous,

low-cost wireless connectivity; tools that enable

rapid software development; big data analytics; and

a new IPv6 internet registration system opening up

340 trillion trillion trillion potential new internet ad-

dresses for individual devices, with protocols that

support greater security, simplify handoffs as de-

vices move across networks, and allow devices to

request addresses autonomously without the need

for IT support.

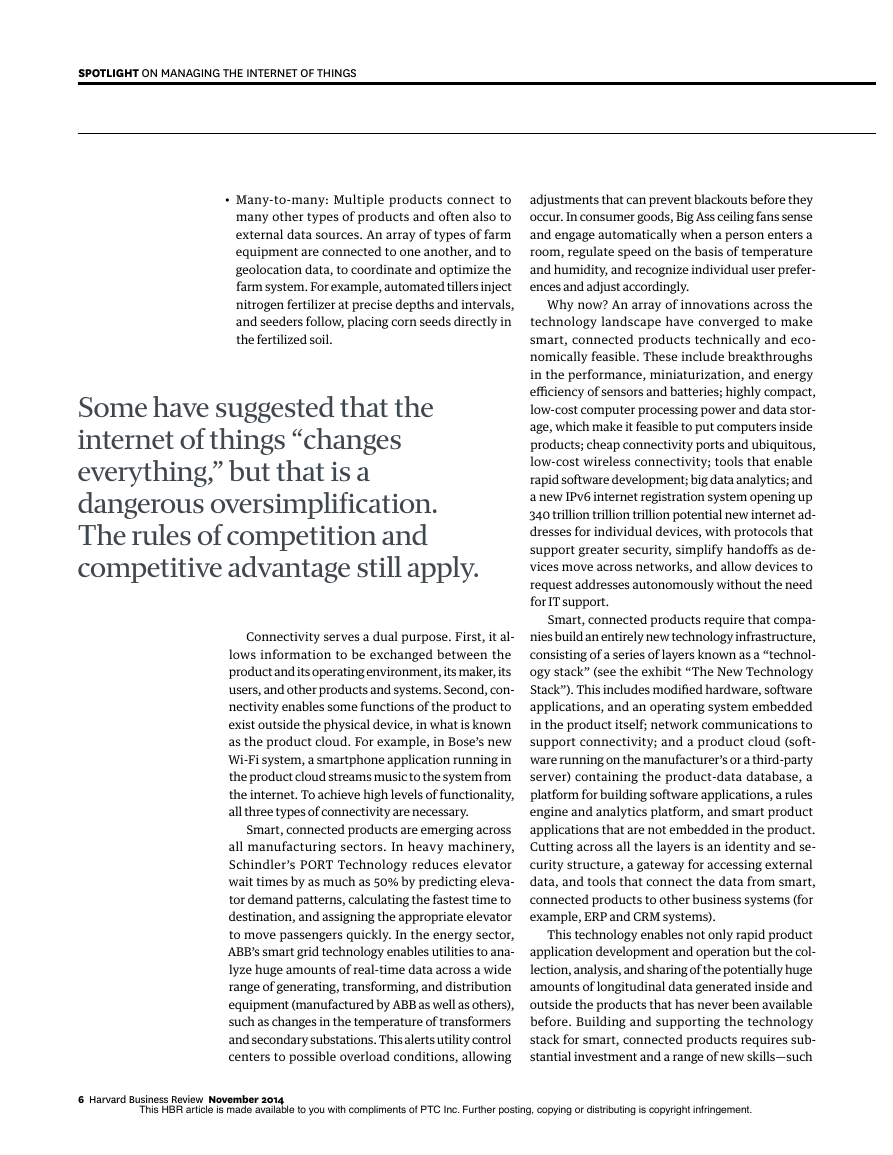

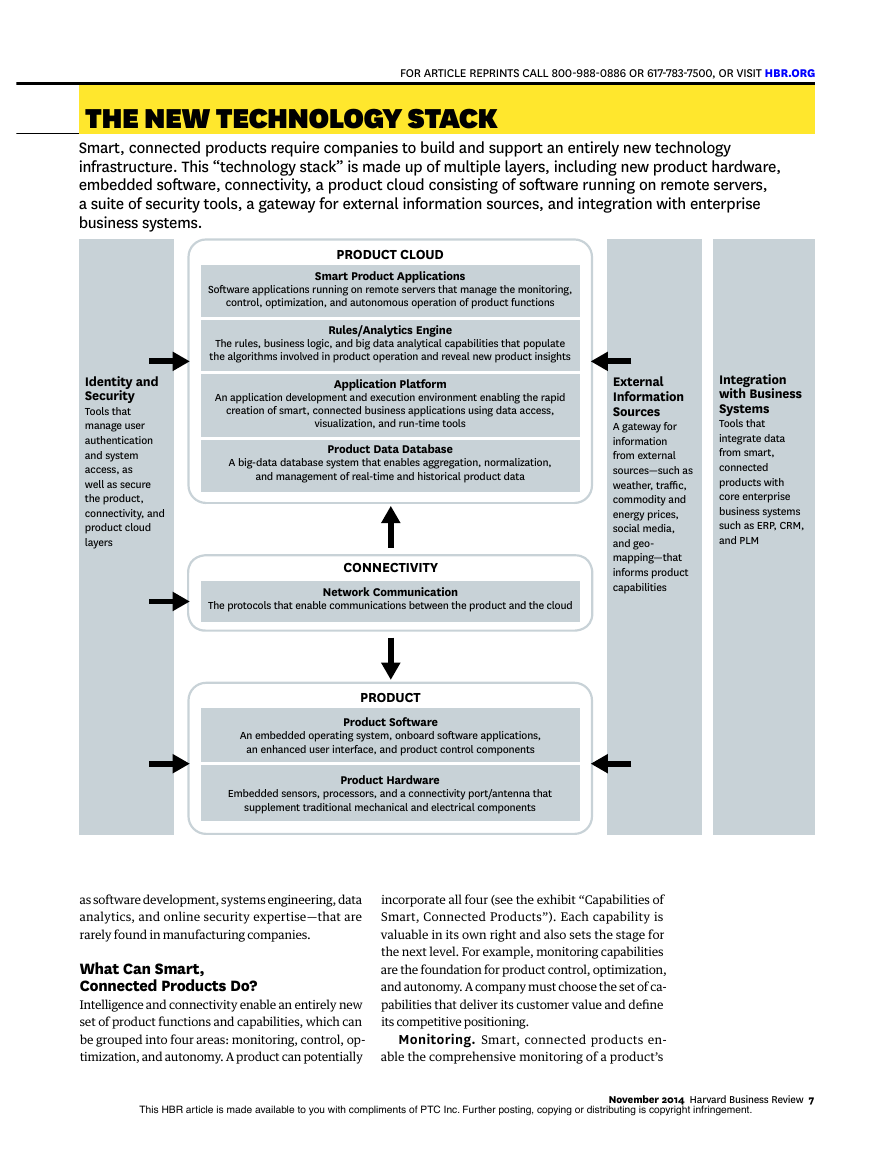

Smart, connected products require that compa-

nies build an entirely new technology infrastructure,

consisting of a series of layers known as a “technol-

ogy stack” (see the exhibit “The New Technology

Stack”). This includes modified hardware, software

applications, and an operating system embedded

in the product itself; network communications to

support connectivity; and a product cloud (soft-

ware running on the manufacturer’s or a third-party

server) containing the product-data database, a

platform for building software applications, a rules

engine and analytics platform, and smart product

applications that are not embedded in the product.

Cutting across all the layers is an identity and se-

curity structure, a gateway for accessing external

data, and tools that connect the data from smart,

connected products to other business systems (for

example, ERP and CRM systems).

�

FOR ARTICLE REPRINTS CALL 800-988-0886 OR 617-783-7500, OR VISIT HBR.ORG

THE NEW TECHNOLOGY STACK

Smart, connected products require companies to build and support an entirely new technology

infrastructure. This “technology stack” is made up of multiple layers, including new product hardware,

embedded software, connectivity, a product cloud consisting of software running on remote servers,

a suite of security tools, a gateway for external information sources, and integration with enterprise

business systems.

PRODUCT CLOUD

Smart Product Applications

Software applications running on remote servers that manage the monitoring,

control, optimization, and autonomous operation of product functions

The rules, business logic, and big data analytical capabilities that populate

the algorithms involved in product operation and reveal new product insights

Rules/Analytics Engine

Identity and

Security

Tools that

manage user

authentication

and system

access, as

well as secure

the product,

connectivity, and

product cloud

layers

Application Platform

An application development and execution environment enabling the rapid

creation of smart, connected business applications using data access,

visualization, and run-time tools

Product Data Database

A big-data database system that enables aggregation, normalization,

and management of real-time and historical product data

CONNECTIVITY

The protocols that enable communications between the product and the cloud

Network Communication

Integration

with Business

Systems

Tools that

integrate data

from smart,

connected

products with

core enterprise

business systems

such as ERP, CRM,

and PLM

External

Information

Sources

A gateway for

information

from external

sources—such as

weather, traffic,

commodity and

energy prices,

social media,

and geo-

mapping—that

informs product

capabilities

PRODUCT

Product Software

An embedded operating system, onboard software applications,

an enhanced user interface, and product control components

Product Hardware

Embedded sensors, processors, and a connectivity port/antenna that

supplement traditional mechanical and electrical components

as software development, systems engineering, data

analytics, and online security expertise—that are

rarely found in manufacturing companies.

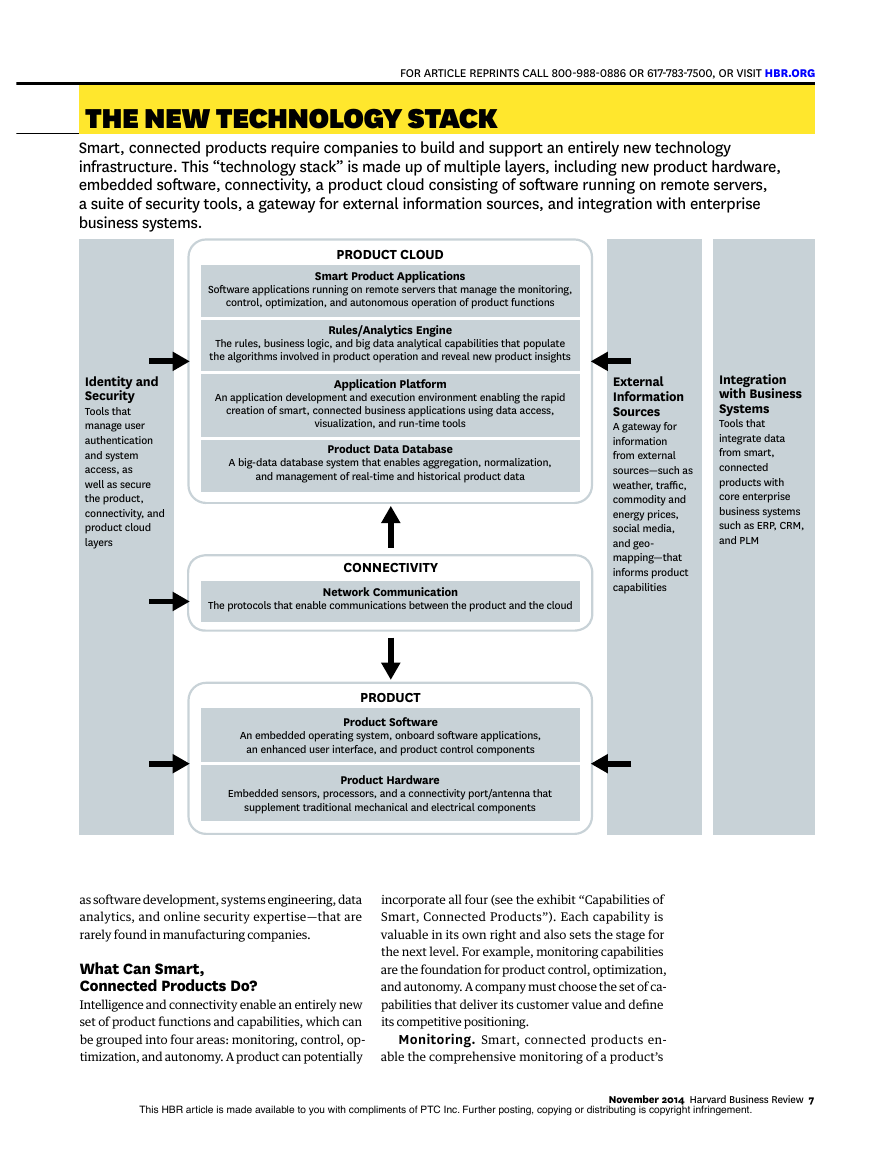

What Can Smart,

Connected Products Do?

Intelligence and connectivity enable an entirely new

set of product functions and capabilities, which can

be grouped into four areas: monitoring, control, op-

timization, and autonomy. A product can potentially

incorporate all four (see the exhibit “Capabilities of

Smart, Connected Products”). Each capability is

valuable in its own right and also sets the stage for

the next level. For example, monitoring capabilities

are the foundation for product control, optimization,

and autonomy. A company must choose the set of ca-

pabilities that deliver its customer value and define

its competitive positioning.

Monitoring. Smart, connected products en-

able the comprehensive monitoring of a product’s

This HBR article is made available to you with compliments of PTC Inc. Further posting, copying or distributing is copyright infringement.

November 2014 Harvard Business Review 7

�

a patient reaches a threshold blood-glucose level, en-

abling appropriate therapy adjustments.

Monitoring capabilities can span multiple prod-

ucts across distances. Joy Global, a leading mining

equipment manufacturer, monitors operating con-

ditions, safety parameters, and predictive service

indicators for entire fleets of equipment far under-

ground. Joy also monitors operating parameters

across multiple mines in different countries for

benchmarking purposes.

Control. Smart, connected products can be con-

trolled through remote commands or algorithms

that are built into the device or reside in the product

cloud. Algorithms are rules that direct the pro-

duct to respond to specified changes in its condition

or environment (for example, “if pressure gets too

high, shut off the valve” or “when traffic in a park-

ing garage reaches a certain level, turn the overhead

lighting on or off”).

SPOTLIGHT ON MANAGING THE INTERNET OF THINGS

condition, operation, and external environment

through sensors and external data sources. Using

data, a product can alert users or others to changes

in circumstances or performance. Monitoring also al-

lows companies and customers to track a product’s

operating characteristics and history and to better un-

derstand how the product is actually used. This data

has important implications for design (by reducing

overengineering, for example), market segmentation

(through the analysis of usage patterns by customer

type), and after-sale service (by allowing the dispatch

of the right technician with the right part, thus im-

proving the first-time fix rate). Monitoring data may

also reveal warranty compliance issues as well as new

sales opportunities, such as the need for additional

product capacity because of high utilization.

In some cases, such as medical devices, monitor-

ing is the core element of value creation. Medtronic’s

digital blood-glucose meter uses a sensor inserted

under the patient’s skin to measure glucose levels in

tissue fluid and connects wirelessly to a device that

alerts patients and clinicians up to 30 minutes before

Control through software embedded in the prod-

uct or the cloud allows the customization of product

performance to a degree that previously was not cost

CAPABILITIES OF SMART,

CONNECTED PRODUCTS

The capabilities of smart, connected products can

be grouped into four areas: monitoring, control,

optimization, and autonomy. Each builds on the

preceding one; to have control capability, for example,

a product must have monitoring capability.

Control

2

Software embedded in the

product or in the product

cloud enables:

• Control of product functions

• Personalization of the user

experience

1

Monitoring

Sensors and external

data sources enable the

comprehensive monitoring of:

• the product’s condition

• the external environment

• the product’s operation

and usage

Monitoring also enables alerts

and notifications of changes

Optimization

Autonomy

4

3

Monitoring and control

capabilities enable algorithms

that optimize product

operation and use in order to:

• Enhance product

performance

• Allow predictive diagnostics,

service, and repair

Combining monitoring, control,

and optimization allows:

• Autonomous product

operation

• Self-coordination of

operation with other

products and systems

• Autonomous product

enhancement and

personalization

• Self-diagnosis and

service

8 Harvard Business Review November 2014

This HBR article is made available to you with compliments of PTC Inc. Further posting, copying or distributing is copyright infringement.

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc