Programming Abstractions

http://www.stanford.edu/class/cs106b/

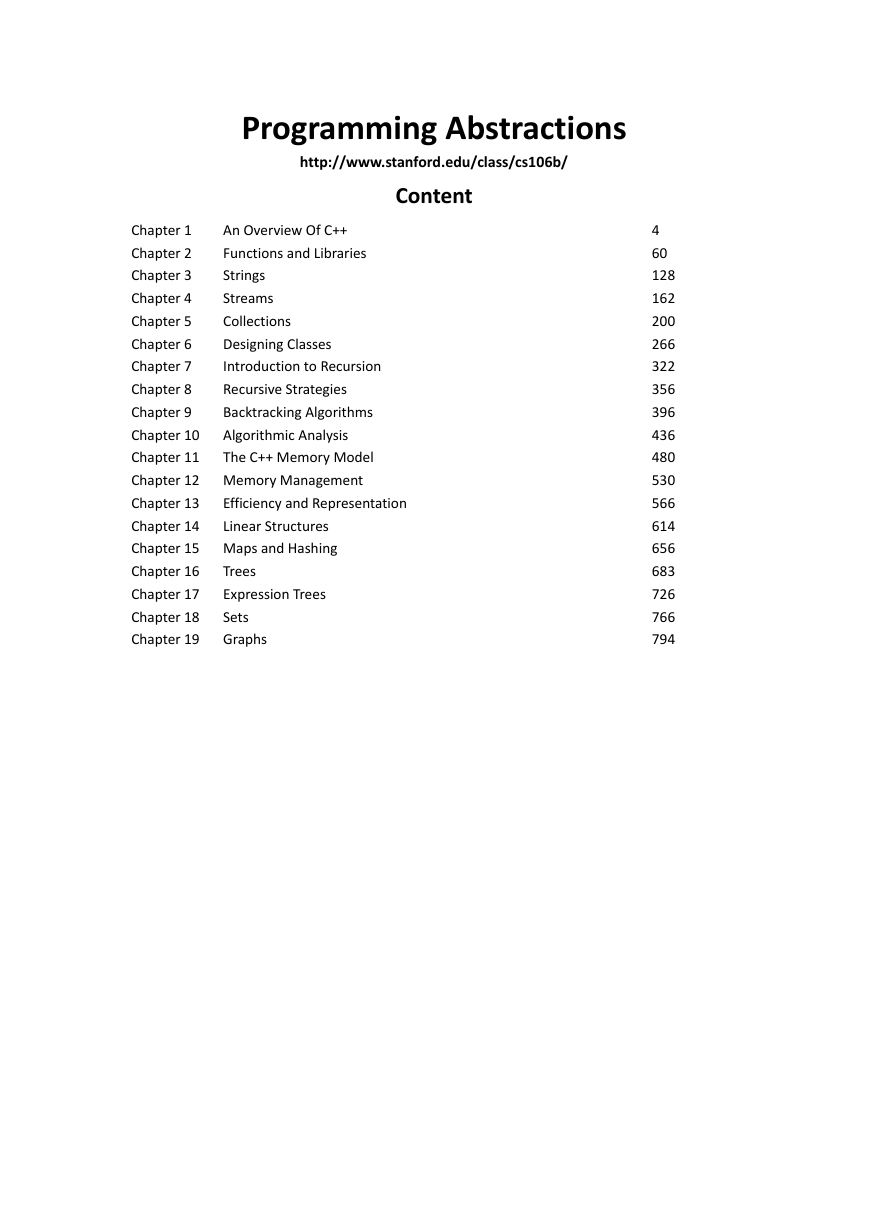

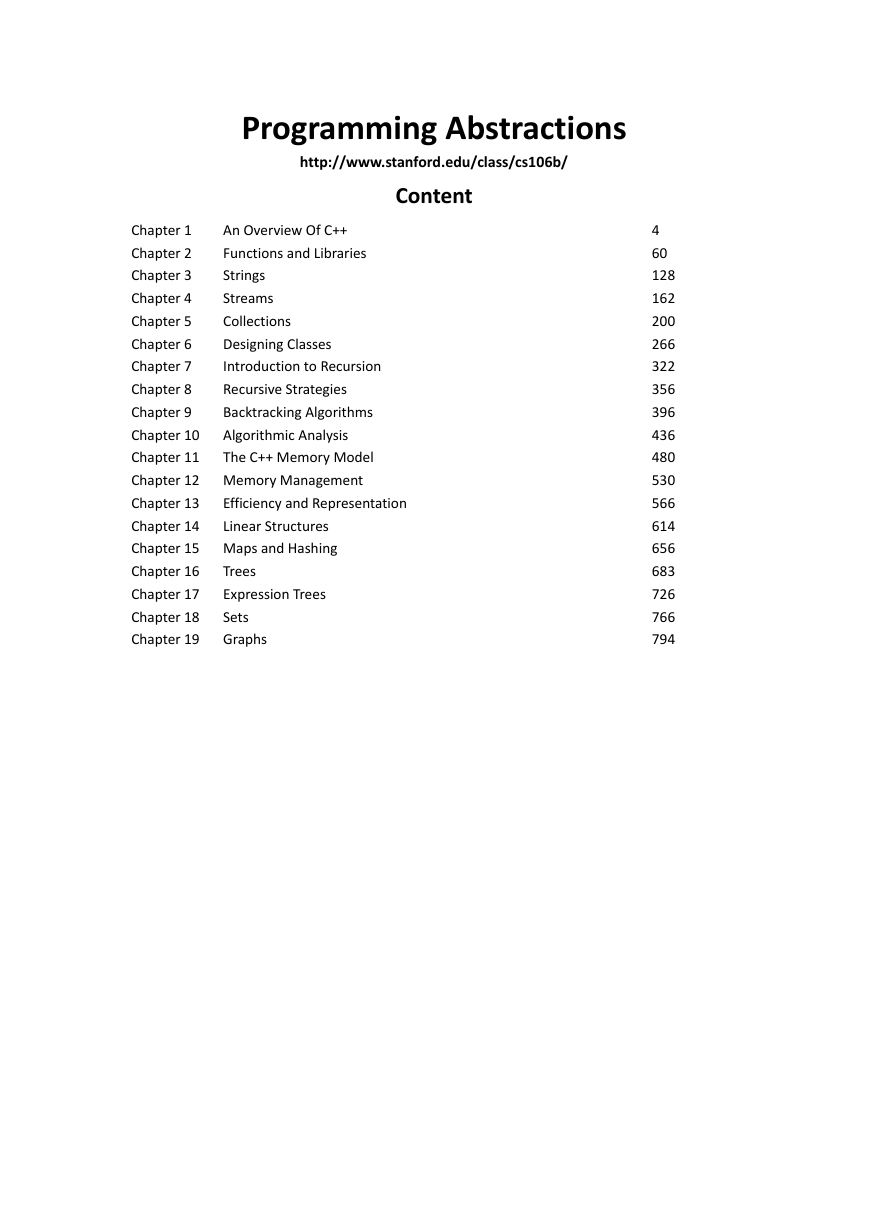

Content

An Overview Of C++

Chapter 1

Functions and Libraries

Chapter 2

Strings

Chapter 3

Streams

Chapter 4

Collections

Chapter 5

Designing Classes

Chapter 6

Introduction to Recursion

Chapter 7

Recursive Strategies

Chapter 8

Backtracking Algorithms

Chapter 9

Chapter 10 Algorithmic Analysis

Chapter 11 The C++ Memory Model

Chapter 12 Memory Management

Chapter 13 Efficiency and Representation

Chapter 14 Linear Structures

Chapter 15 Maps and Hashing

Chapter 16 Trees

Chapter 17 Expression Trees

Chapter 18 Sets

Chapter 19 Graphs

4

60

128

162

200

266

322

356

396

436

480

530

566

614

656

683

726

766

794

�

Programming Abstractions in C++

(Chapters 1–13)

Eric S. Roberts

This text represents a major revision of the course reader that we’ve been using at

Stanford for the last several years. The primary goal of the revision was to bring the

approach more closely in line with the way C++ is used in industry, which will in turn

make it easier to export Stanford’s approach to teaching data structures to a larger

fraction of schools. As of yet, the draft text is extremely rough and has not been

copy-edited as the book will be. This installment contains only 13 out of the 19 chapters

in the outline. The remaining chapters will be distributed as handouts during the quarter.

This textbook has had an interesting evolutionary history that in some ways mirrors

the genesis of the C++ language itself. Just as Bjarne Stroustup’s first version of C++

was implemented on top of a C language base, this reader began its life as Eric Roberts’s

textbook Programming Abstractions in C (Addison-Wesley, 1998). In 2002-03, Julie

Zelenski updated it for use with the C++ programming language, which we began using

in CS106B and CS106X during that year. Although the revised text worked fairly well at

the outset, CS106B and CS106X have evolved in recent years so that their structure no

longer tracks the organization of the book. In 2008, I embarked on a comprehensive in

the process of rewriting the book so that students in these courses can use it as both a

tutorial and a reference. As always, that process takes a considerable amount of time, and

there are certain to be some problems in the revision. At the same time, I’m convinced

that the material in CS106B and CS106X is tremendously exciting and will be able to

carry us through a quarter of instability, as we turn the reader into a book that can be used

at universities and colleges around the world.

I want to thank my colleagues at Stanford over the last several years, starting with Julie

Zelenski for her extensive work on the initial C++ revision. My colleagues Keith

Schwarz, Jerry Cain, Stephen Cooper, and Mehran Sahami have all made important

contributions to the revision. And I also need to express my thanks to several generations

of section leaders and so many students over the years, all of whom have helped make it

so exciting to teach this wonderful material.

�

�

Chapter 1

An Overview of C++

Out of these various experiments come programs. This is our

experience: programs do not come out of the minds of one person

or two people such as ourselves, but out of day-to-day work.

— Stokely Carmichael and Charles V. Hamilton,

Black Power, 1967

�

2 Overview of C++

In Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the King asks the White

Rabbit to “begin at the beginning and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

Good advice, but only if you’re starting from the beginning. This book is designed

for a second course in computer science and therefore assumes that you have

already begun your study of programming. At the same time, because first courses

vary considerably in what they cover, it is difficult to rely on any specific material.

Some of you, for example, will already understand C++ control structures from

prior experience with closely related languages such as C or Java. For others,

however, the structure of C++ will seem unfamiliar. Because of this disparity in

background, the best approach is to adopt the King’s advice. This chapter therefore

“begins at the beginning” and introduces you to those parts of the C++ language

you will need to write simple programs

1.1 Your first C++ program

As you will learn in more detail in the following section, C++ is an extension of an

extremely successful programming language called C, which appeared in the early

1970s. In the book that serves as C’s defining document, The C Programming

Language, Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie offer the following advice on the

first page of Chapter 1.

The only way to learn a new programming language is by

writing programs in it. The first program to write is the same

for all languages:

Print the words

hello, world

This is the big hurdle; to leap over it you have to be able to

create the program text somewhere, compile it successfully,

load it, run it, and find out where the output went. With these

mechanical details mastered, everything else is comparatively

easy.

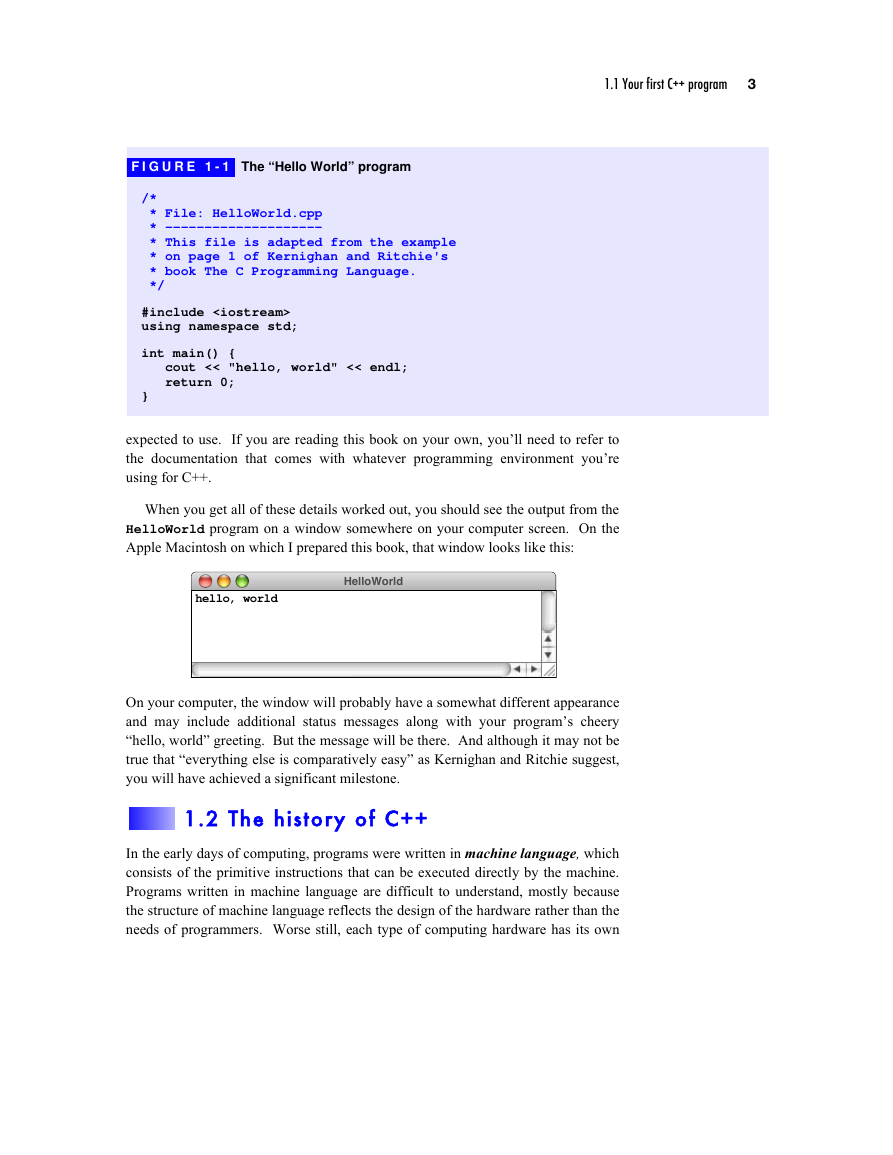

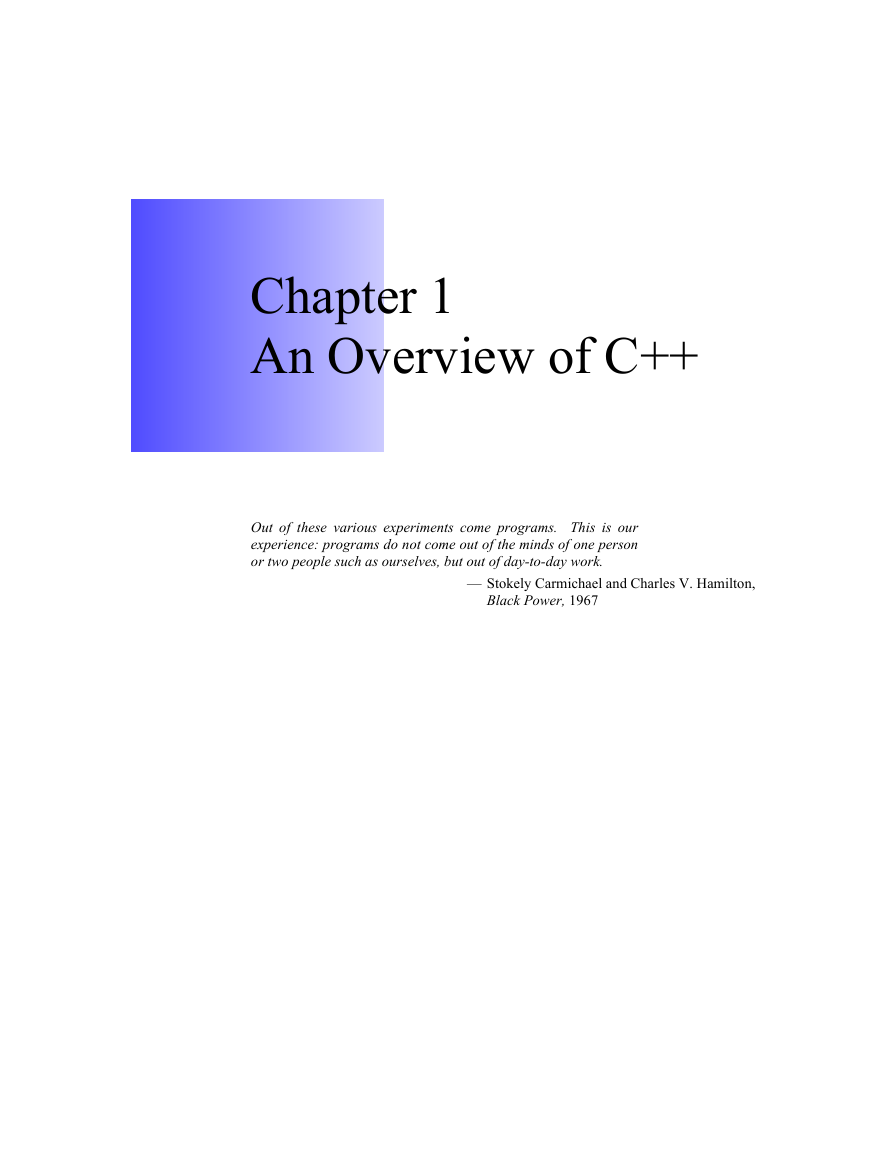

If you were to rewrite it in C++, the “Hello World” program would end up looking

something like the code in Figure 1-1.

At this point, the important thing is not to understand exactly what all of the

lines in this program mean. There is plenty of time to master those details later.

Your mission—and you should decide to accept it—is to get the HelloWorld

program running. Type in the program exactly as it appears in Figure 1-1 and then

figure out what you need to do to make it work. The exact steps you need to use

depend on the programming environment you’re using to create and run C++

programs. If you are using this textbook for a class, your instructor will presumably

provide some reference material on the programming environments you are

�

1.1 Your first C++ program 3

F I G U R E 1 - 1 The “Hello World” program

/*

* File: HelloWorld.cpp

* --------------------

* This file is adapted from the example

* on page 1 of Kernighan and Ritchie's

* book The C Programming Language.

*/

#include

using namespace std;

int main() {

cout << "hello, world" << endl;

return 0;

}

expected to use. If you are reading this book on your own, you’ll need to refer to

the documentation that comes with whatever programming environment you’re

using for C++.

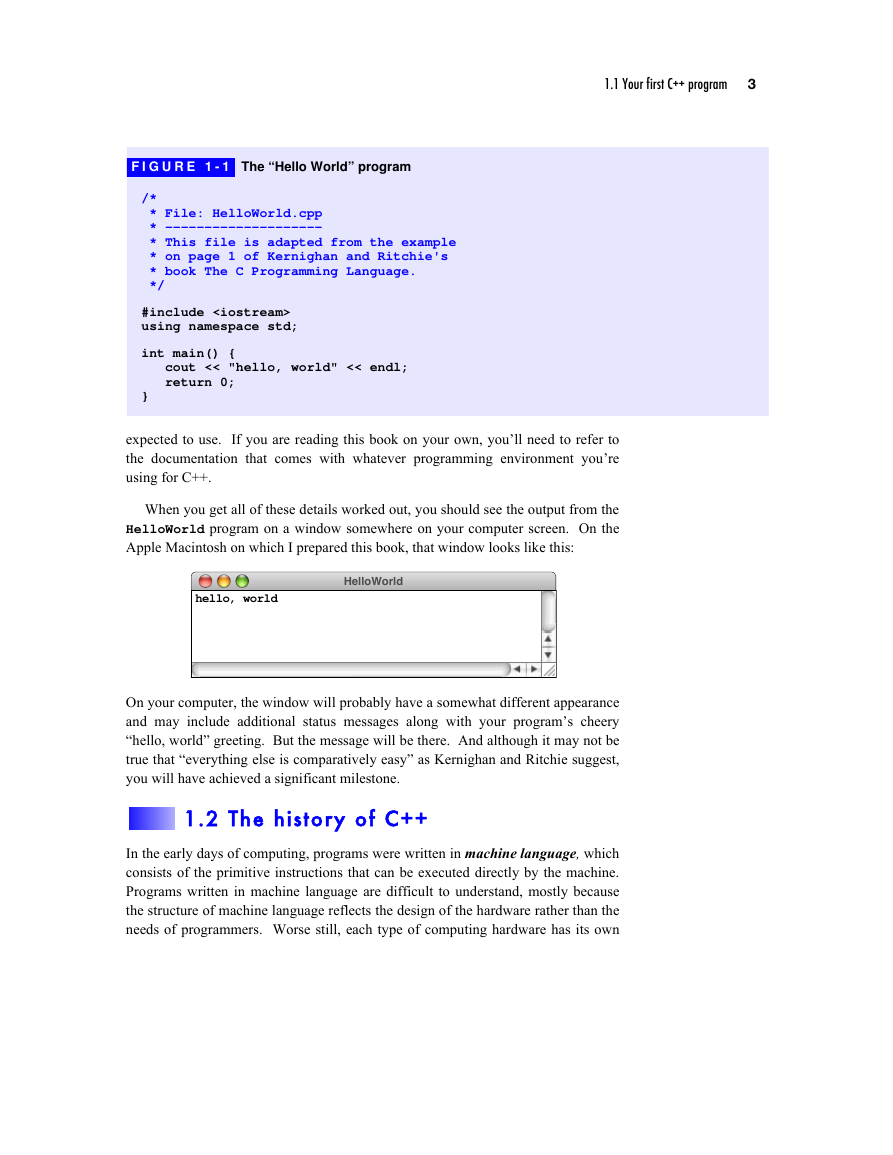

When you get all of these details worked out, you should see the output from the

HelloWorld program on a window somewhere on your computer screen. On the

Apple Macintosh on which I prepared this book, that window looks like this:

HelloWorld

hello, world

On your computer, the window will probably have a somewhat different appearance

and may include additional status messages along with your program’s cheery

“hello, world” greeting. But the message will be there. And although it may not be

true that “everything else is comparatively easy” as Kernighan and Ritchie suggest,

you will have achieved a significant milestone.

1.2 The history of C++

In the early days of computing, programs were written in machine language, which

consists of the primitive instructions that can be executed directly by the machine.

Programs written in machine language are difficult to understand, mostly because

the structure of machine language reflects the design of the hardware rather than the

needs of programmers. Worse still, each type of computing hardware has its own

�

4 Overview of C++

machine language, which means that a program written for one machine will not run

on other types of hardware.

In the mid-1950s, a group of programmers under the direction of John Backus at

IBM had an idea that profoundly changed the nature of computing. Would it be

possible, Backus and his colleagues wondered, to write programs that resembled the

mathematical formulas they were trying to compute and have the computer itself

translate those formulas into machine language? In 1955, this team produced the

initial version of FORTRAN (whose name is a contraction of formula translation),

which was the first example of a higher-level programming language.

Since that time, many new programming languages have been invented, most of

which build on previous languages in an evolutionary way. C++ represents the

joining of two branches in that evolution. One of its ancestors is a language called

C, which was designed at Bell Laboratories by Dennis Ritchie in 1972 and then

later revised and standardized by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI)

in 1989. But C++ also descends from a family of languages designed to support a

different style of programming that has dramatically changed the nature of software

development in recent years.

The object-oriented paradigm

Over the last two decades, computer science and programming have gone through

something of a revolution. Like most revolutions—whether political upheavals or

the conceptual restructurings that Thomas Kuhn describes in his 1962 book The

Structure of Scientific Revolutions—this change has been driven by the emergence

of an idea that challenges an existing orthodoxy. Initially, the two ideas compete,

and, at least for a while, the old order maintains its dominance. Over time,

however, the strength and popularity of the new idea grows, until it begins to

displace the older idea in what Kuhn calls a paradigm shift. In programming, the

old order is represented by the procedural paradigm, in which programs consist of

a collection of procedures and functions that operate on data. The new model is

called the object-oriented paradigm, in which programs are viewed instead as a

collection of data objects that embody particular characteristics and behavior.

The idea of object-oriented programming is not really all that new. The first

object-oriented language was SIMULA, a language for coding simulations designed

by the Scandinavian computer scientists Ole-Johan Dahl, Björn Myhrhaug, and

Kristen Nygaard in 1967. With a design that was far ahead of its time, SIMULA

anticipated many of the concepts that later became commonplace in programming,

including the concept of abstract data types and much of the modern object-oriented

paradigm. In fact, much of the terminology used to describe object-oriented

languages comes from the original 1967 report on SIMULA.

�

1.2 The history of C++ 5

Unfortunately, SIMULA did not generate a great deal of interest in the years

after its introduction. The first object-oriented language to gain any significant

following within the computing profession was Smalltalk, which was developed at

the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center in the late 1970s. The purpose of Smalltalk,

which is described in the book Smalltalk-80: The Language and Its Implementation

by Adele Goldberg and David Robson, was to make programming accessible to a

wider audience. As such, Smalltalk was part of a larger effort at Xerox PARC that

gave rise to much of the modern user-interface technology that is now standard on

personal computers.

Despite many attractive features and a highly interactive user environment that

simplifies the programming process, Smalltalk never achieved much commercial

success. The profession as a whole took an interest in object-oriented programming

only when the central ideas were incorporated into variants of C, which had already

become an industry standard. Although there were several parallel efforts to design

an object-oriented language based on C, the most successful was the language C++,

which was developed by Bjarne Stroustrup at AT&T Bell Laboratories in the early

1980s. C++ includes standard C as a subset, which makes it possible to integrate

C++ code into existing C programs in a gradual, evolutionary way

Although object-oriented languages have gained some of their popularity at the

expense of procedural ones, it would be a mistake to regard the object-oriented and

procedural paradigms as mutually exclusive. Programming paradigms are not so

much competitive as they are complementary. The object-oriented and the

procedural paradigm—along with other important paradigms such as the functional

programming style embodied in LISP—all have important applications in practice.

Even within the context of a single application, you are likely to find a use for more

than one approach. As a programmer, you must master many different paradigms,

so that you can use the conceptual model that is most appropriate to the task at

hand.

The compilation process

When you write a program in C++, your first step is to create a file that contains the

text of the program, which is called a source file. Before you can run your

program, you need to translate the source file into an executable form. The first

step in that process is to invoke a program called a compiler, which translates the

source file into an object file containing the corresponding machine-language

instructions. This object file is then combined with other object files to produce an

executable file that can be run on the system. The other object files typically

include predefined object files called libraries that contain the machine-language

instructions for various operations commonly required by programs. The process of

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc