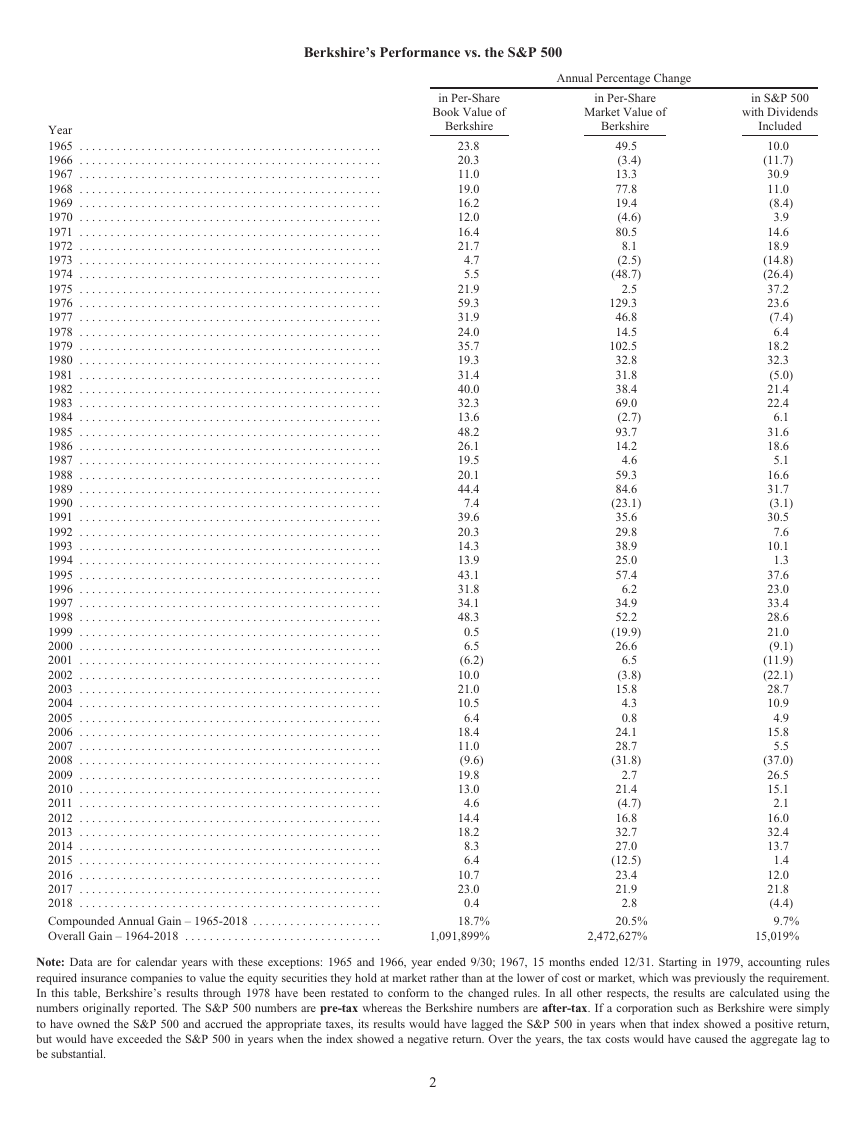

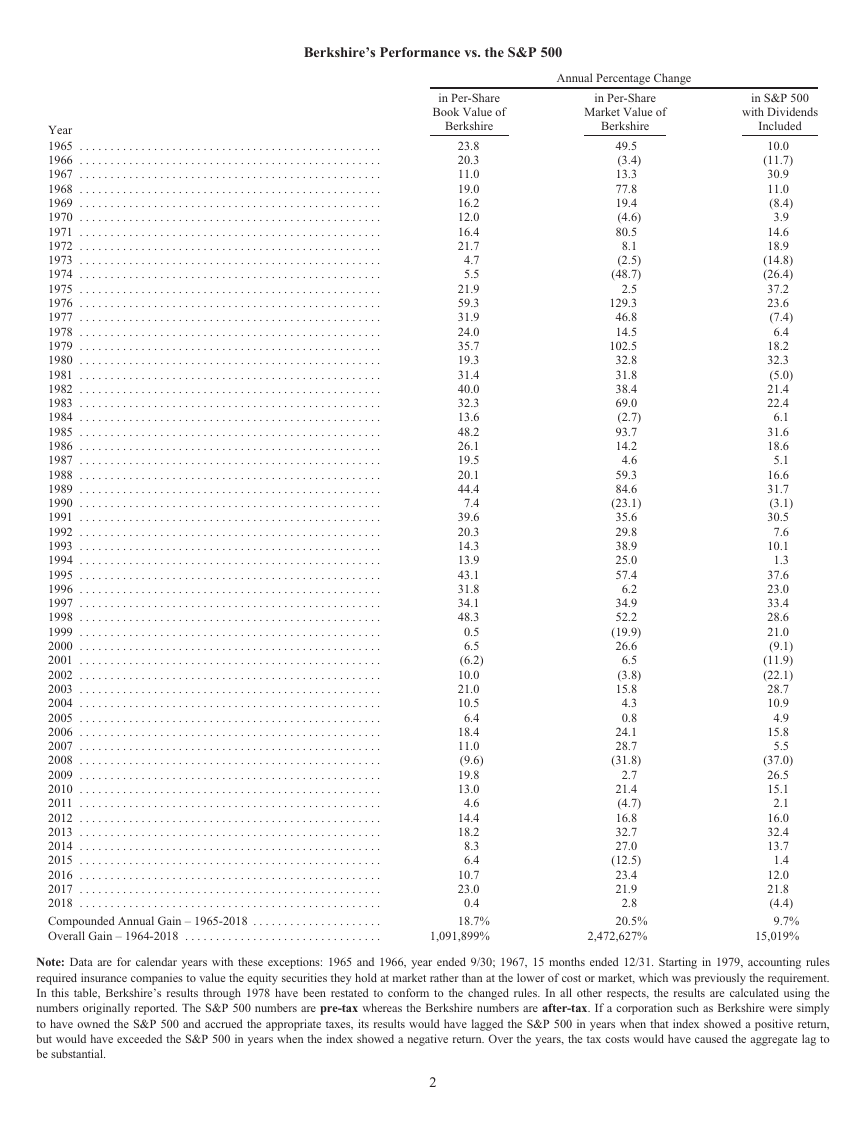

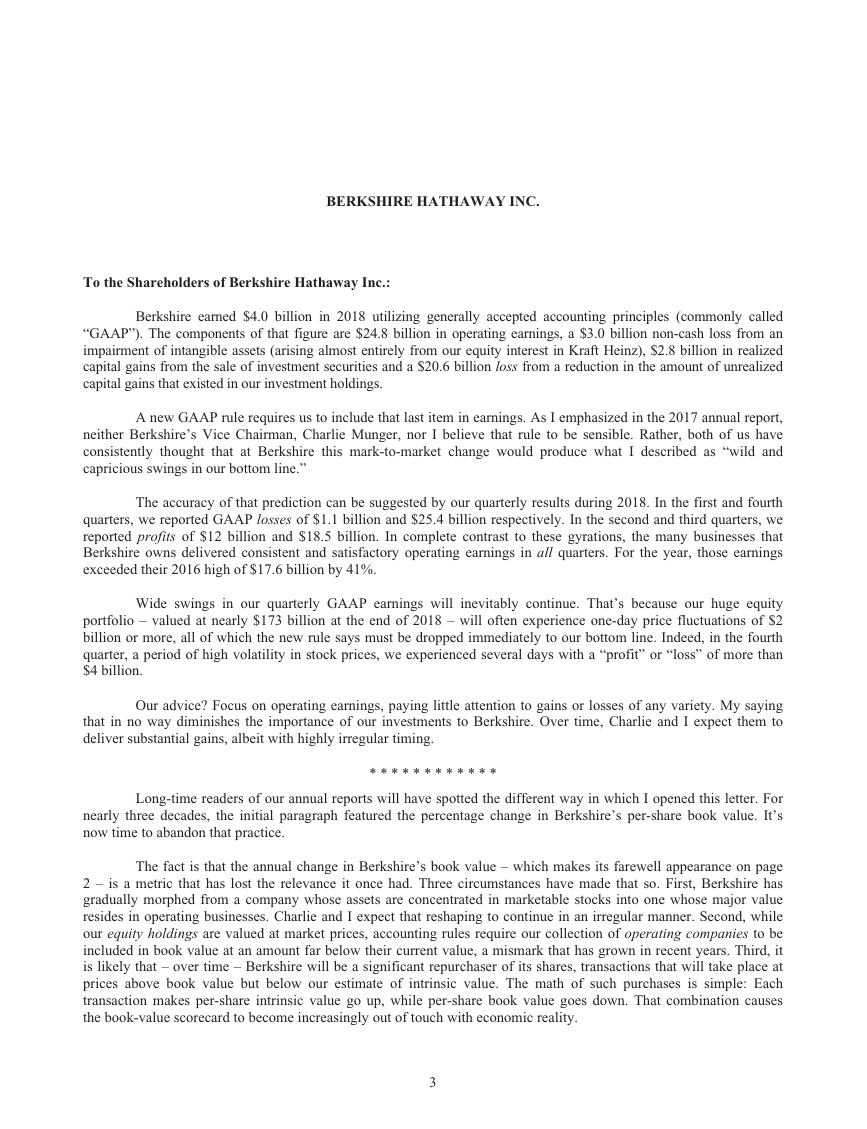

Berkshire’s Performance vs. the S&P 500

Year

1965 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1966 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1967 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1968 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1969 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1970 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1971 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1972 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1973 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1974 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1975 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1976 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1977 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1978 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1979 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1980 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1981 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1982 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1983 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1984 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1985 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1986 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1987 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1988 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1989 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1990 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1991 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1992 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1993 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1994 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1995 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1996 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1997 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1998 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1999 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2001 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2002 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2003 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2004 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2005 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2006 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2008 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2009 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2010 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2011 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2012 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2013 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2014 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2015 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2016 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2017 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2018 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Compounded Annual Gain – 1965-2018 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Overall Gain – 1964-2018 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

in Per-Share

Book Value of

Berkshire

Annual Percentage Change

in Per-Share

Market Value of

Berkshire

in S&P 500

with Dividends

Included

23.8

20.3

11.0

19.0

16.2

12.0

16.4

21.7

4.7

5.5

21.9

59.3

31.9

24.0

35.7

19.3

31.4

40.0

32.3

13.6

48.2

26.1

19.5

20.1

44.4

7.4

39.6

20.3

14.3

13.9

43.1

31.8

34.1

48.3

0.5

6.5

(6.2)

10.0

21.0

10.5

6.4

18.4

11.0

(9.6)

19.8

13.0

4.6

14.4

18.2

8.3

6.4

10.7

23.0

0.4

18.7%

1,091,899%

49.5

(3.4)

13.3

77.8

19.4

(4.6)

80.5

8.1

(2.5)

(48.7)

2.5

129.3

46.8

14.5

102.5

32.8

31.8

38.4

69.0

(2.7)

93.7

14.2

4.6

59.3

84.6

(23.1)

35.6

29.8

38.9

25.0

57.4

6.2

34.9

52.2

(19.9)

26.6

6.5

(3.8)

15.8

4.3

0.8

24.1

28.7

(31.8)

2.7

21.4

(4.7)

16.8

32.7

27.0

(12.5)

23.4

21.9

2.8

20.5%

2,472,627%

10.0

(11.7)

30.9

11.0

(8.4)

3.9

14.6

18.9

(14.8)

(26.4)

37.2

23.6

(7.4)

6.4

18.2

32.3

(5.0)

21.4

22.4

6.1

31.6

18.6

5.1

16.6

31.7

(3.1)

30.5

7.6

10.1

1.3

37.6

23.0

33.4

28.6

21.0

(9.1)

(11.9)

(22.1)

28.7

10.9

4.9

15.8

5.5

(37.0)

26.5

15.1

2.1

16.0

32.4

13.7

1.4

12.0

21.8

(4.4)

9.7%

15,019%

Note: Data are for calendar years with these exceptions: 1965 and 1966, year ended 9/30; 1967, 15 months ended 12/31. Starting in 1979, accounting rules

required insurance companies to value the equity securities they hold at market rather than at the lower of cost or market, which was previously the requirement.

In this table, Berkshire’s results through 1978 have been restated to conform to the changed rules. In all other respects, the results are calculated using the

numbers originally reported. The S&P 500 numbers are pre-tax whereas the Berkshire numbers are after-tax. If a corporation such as Berkshire were simply

to have owned the S&P 500 and accrued the appropriate taxes, its results would have lagged the S&P 500 in years when that index showed a positive return,

but would have exceeded the S&P 500 in years when the index showed a negative return. Over the years, the tax costs would have caused the aggregate lag to

be substantial.

2

�

BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC.

To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

Berkshire earned $4.0 billion in 2018 utilizing generally accepted accounting principles (commonly called

“GAAP”). The components of that figure are $24.8 billion in operating earnings, a $3.0 billion non-cash loss from an

impairment of intangible assets (arising almost entirely from our equity interest in Kraft Heinz), $2.8 billion in realized

capital gains from the sale of investment securities and a $20.6 billion loss from a reduction in the amount of unrealized

capital gains that existed in our investment holdings.

A new GAAP rule requires us to include that last item in earnings. As I emphasized in the 2017 annual report,

neither Berkshire’s Vice Chairman, Charlie Munger, nor I believe that rule to be sensible. Rather, both of us have

consistently thought that at Berkshire this mark-to-market change would produce what I described as “wild and

capricious swings in our bottom line.”

The accuracy of that prediction can be suggested by our quarterly results during 2018. In the first and fourth

quarters, we reported GAAP losses of $1.1 billion and $25.4 billion respectively. In the second and third quarters, we

reported profits of $12 billion and $18.5 billion. In complete contrast to these gyrations, the many businesses that

Berkshire owns delivered consistent and satisfactory operating earnings in all quarters. For the year, those earnings

exceeded their 2016 high of $17.6 billion by 41%.

Wide swings in our quarterly GAAP earnings will inevitably continue. That’s because our huge equity

portfolio – valued at nearly $173 billion at the end of 2018 – will often experience one-day price fluctuations of $2

billion or more, all of which the new rule says must be dropped immediately to our bottom line. Indeed, in the fourth

quarter, a period of high volatility in stock prices, we experienced several days with a “profit” or “loss” of more than

$4 billion.

Our advice? Focus on operating earnings, paying little attention to gains or losses of any variety. My saying

that in no way diminishes the importance of our investments to Berkshire. Over time, Charlie and I expect them to

deliver substantial gains, albeit with highly irregular timing.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

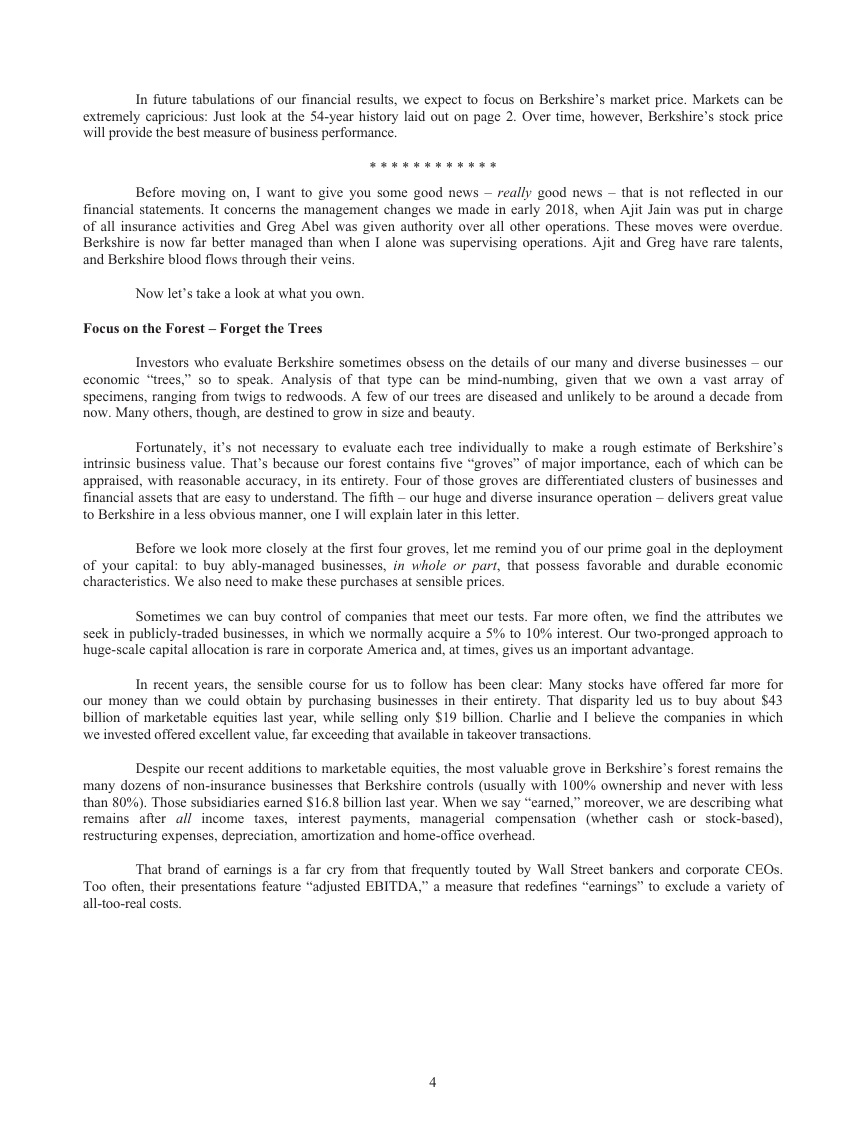

Long-time readers of our annual reports will have spotted the different way in which I opened this letter. For

nearly three decades, the initial paragraph featured the percentage change in Berkshire’s per-share book value. It’s

now time to abandon that practice.

The fact is that the annual change in Berkshire’s book value – which makes its farewell appearance on page

2 – is a metric that has lost the relevance it once had. Three circumstances have made that so. First, Berkshire has

gradually morphed from a company whose assets are concentrated in marketable stocks into one whose major value

resides in operating businesses. Charlie and I expect that reshaping to continue in an irregular manner. Second, while

our equity holdings are valued at market prices, accounting rules require our collection of operating companies to be

included in book value at an amount far below their current value, a mismark that has grown in recent years. Third, it

is likely that – over time – Berkshire will be a significant repurchaser of its shares, transactions that will take place at

prices above book value but below our estimate of intrinsic value. The math of such purchases is simple: Each

transaction makes per-share intrinsic value go up, while per-share book value goes down. That combination causes

the book-value scorecard to become increasingly out of touch with economic reality.

3

�

In future tabulations of our financial results, we expect to focus on Berkshire’s market price. Markets can be

extremely capricious: Just look at the 54-year history laid out on page 2. Over time, however, Berkshire’s stock price

will provide the best measure of business performance.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Before moving on, I want to give you some good news – really good news – that is not reflected in our

financial statements. It concerns the management changes we made in early 2018, when Ajit Jain was put in charge

of all insurance activities and Greg Abel was given authority over all other operations. These moves were overdue.

Berkshire is now far better managed than when I alone was supervising operations. Ajit and Greg have rare talents,

and Berkshire blood flows through their veins.

Now let’s take a look at what you own.

Focus on the Forest – Forget the Trees

Investors who evaluate Berkshire sometimes obsess on the details of our many and diverse businesses – our

economic “trees,” so to speak. Analysis of that type can be mind-numbing, given that we own a vast array of

specimens, ranging from twigs to redwoods. A few of our trees are diseased and unlikely to be around a decade from

now. Many others, though, are destined to grow in size and beauty.

Fortunately, it’s not necessary to evaluate each tree individually to make a rough estimate of Berkshire’s

intrinsic business value. That’s because our forest contains five “groves” of major importance, each of which can be

appraised, with reasonable accuracy, in its entirety. Four of those groves are differentiated clusters of businesses and

financial assets that are easy to understand. The fifth – our huge and diverse insurance operation – delivers great value

to Berkshire in a less obvious manner, one I will explain later in this letter.

Before we look more closely at the first four groves, let me remind you of our prime goal in the deployment

of your capital: to buy ably-managed businesses, in whole or part, that possess favorable and durable economic

characteristics. We also need to make these purchases at sensible prices.

Sometimes we can buy control of companies that meet our tests. Far more often, we find the attributes we

seek in publicly-traded businesses, in which we normally acquire a 5% to 10% interest. Our two-pronged approach to

huge-scale capital allocation is rare in corporate America and, at times, gives us an important advantage.

In recent years, the sensible course for us to follow has been clear: Many stocks have offered far more for

our money than we could obtain by purchasing businesses in their entirety. That disparity led us to buy about $43

billion of marketable equities last year, while selling only $19 billion. Charlie and I believe the companies in which

we invested offered excellent value, far exceeding that available in takeover transactions.

Despite our recent additions to marketable equities, the most valuable grove in Berkshire’s forest remains the

many dozens of non-insurance businesses that Berkshire controls (usually with 100% ownership and never with less

than 80%). Those subsidiaries earned $16.8 billion last year. When we say “earned,” moreover, we are describing what

remains after all

interest payments, managerial compensation (whether cash or stock-based),

restructuring expenses, depreciation, amortization and home-office overhead.

income taxes,

That brand of earnings is a far cry from that frequently touted by Wall Street bankers and corporate CEOs.

Too often, their presentations feature “adjusted EBITDA,” a measure that redefines “earnings” to exclude a variety of

all-too-real costs.

4

�

For example, managements sometimes assert that their company’s stock-based compensation shouldn’t be

counted as an expense. (What else could it be – a gift from shareholders?) And restructuring expenses? Well, maybe

last year’s exact rearrangement won’t recur. But restructurings of one sort or another are common in business –

Berkshire has gone down that road dozens of times, and our shareholders have always borne the costs of doing so.

Abraham Lincoln once posed the question: “If you call a dog’s tail a leg, how many legs does it have?” and

then answered his own query: “Four, because calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it one.” Abe would have felt lonely on

Wall Street.

Charlie and I do contend that our acquisition-related amortization expenses of $1.4 billion (detailed on page

K-84) are not a true economic cost. We add back such amortization “costs” to GAAP earnings when we are evaluating

both private businesses and marketable stocks.

In contrast, Berkshire’s $8.4 billion depreciation charge understates our true economic cost. In fact, we need

to spend more than this sum annually to simply remain competitive in our many operations. Beyond those

“maintenance” capital expenditures, we spend large sums in pursuit of growth. Overall, Berkshire invested a record

$14.5 billion last year in plant, equipment and other fixed assets, with 89% of that spent in America.

Berkshire’s runner-up grove by value is its collection of equities, typically involving a 5% to 10% ownership

position in a very large company. As noted earlier, our equity investments were worth nearly $173 billion at yearend,

an amount far above their cost. If the portfolio had been sold at its yearend valuation, federal income tax of about

$14.7 billion would have been payable on the gain. In all likelihood, we will hold most of these stocks for a long time.

Eventually, however, gains generate taxes at whatever rate prevails at the time of sale.

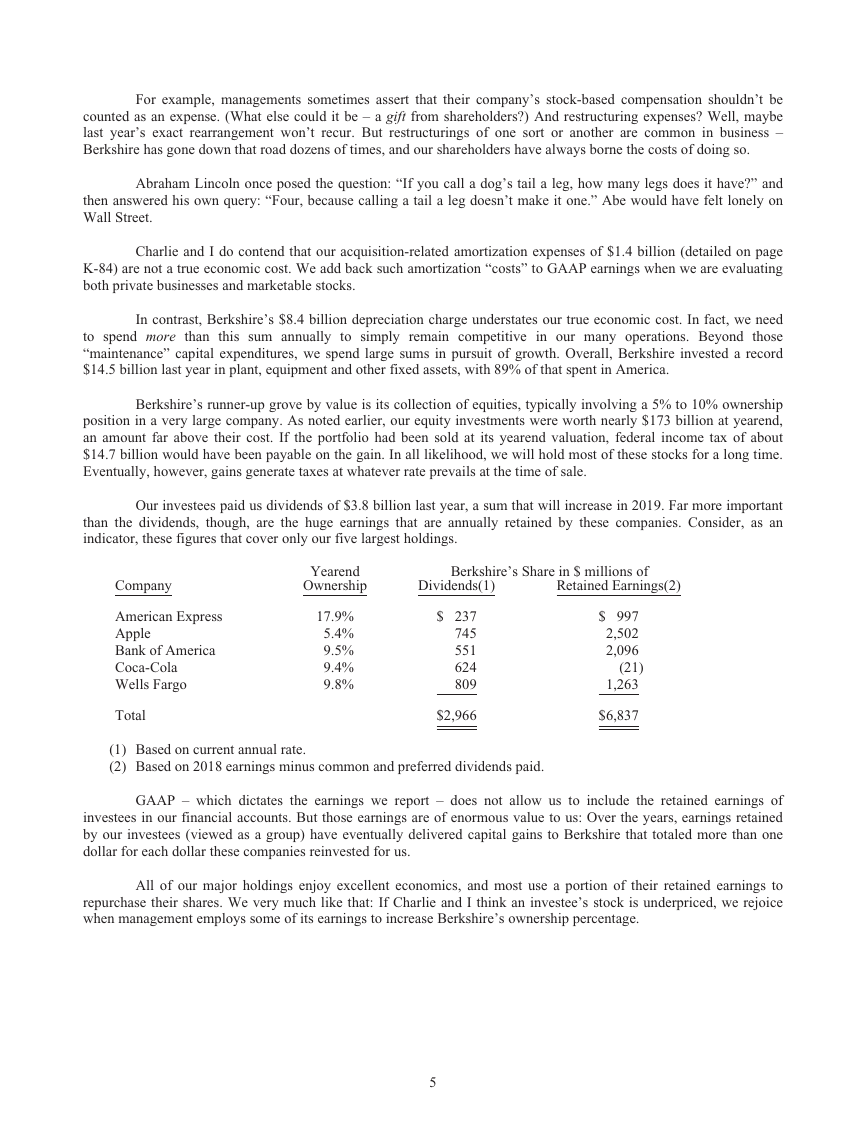

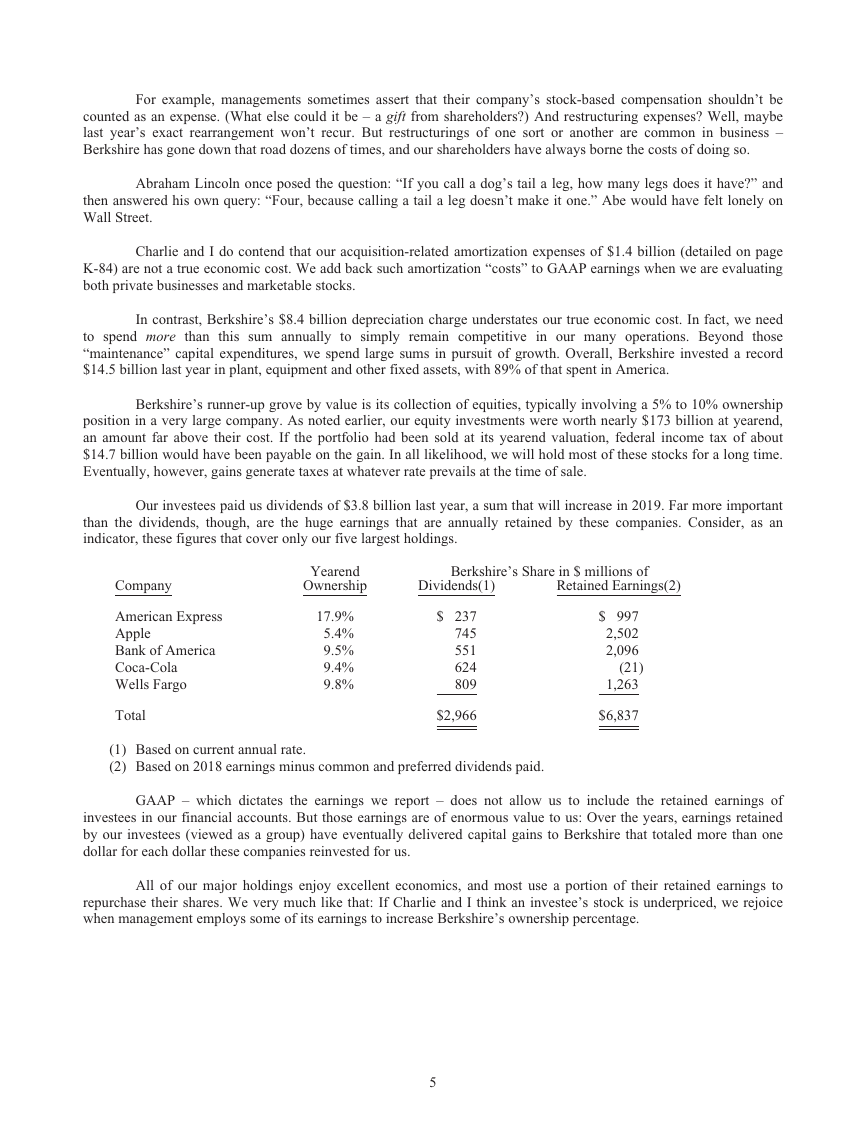

Our investees paid us dividends of $3.8 billion last year, a sum that will increase in 2019. Far more important

than the dividends, though, are the huge earnings that are annually retained by these companies. Consider, as an

indicator, these figures that cover only our five largest holdings.

Company

American Express

Apple

Bank of America

Coca-Cola

Wells Fargo

Total

Yearend

Ownership

17.9%

5.4%

9.5%

9.4%

9.8%

Berkshire’s Share in $ millions of

Dividends(1)

Retained Earnings(2)

$ 237

745

551

624

809

$2,966

$ 997

2,502

2,096

(21)

1,263

$6,837

(1) Based on current annual rate.

(2) Based on 2018 earnings minus common and preferred dividends paid.

GAAP – which dictates the earnings we report – does not allow us to include the retained earnings of

investees in our financial accounts. But those earnings are of enormous value to us: Over the years, earnings retained

by our investees (viewed as a group) have eventually delivered capital gains to Berkshire that totaled more than one

dollar for each dollar these companies reinvested for us.

All of our major holdings enjoy excellent economics, and most use a portion of their retained earnings to

repurchase their shares. We very much like that: If Charlie and I think an investee’s stock is underpriced, we rejoice

when management employs some of its earnings to increase Berkshire’s ownership percentage.

5

�

Here’s one example drawn from the table above: Berkshire’s holdings of American Express have remained

unchanged over the past eight years. Meanwhile, our ownership increased from 12.6% to 17.9% because of

repurchases made by the company. Last year, Berkshire’s portion of the $6.9 billion earned by American Express was

$1.2 billion, about 96% of the $1.3 billion we paid for our stake in the company. When earnings increase and shares

outstanding decrease, owners – over time – usually do well.

A third category of Berkshire’s business ownership is a quartet of companies in which we share control with

other parties. Our portion of the after-tax operating earnings of these businesses – 26.7% of Kraft Heinz, 50% of

Berkadia and Electric Transmission Texas, and 38.6% of Pilot Flying J – totaled about $1.3 billion in 2018.

In our fourth grove, Berkshire held $112 billion at yearend in U.S. Treasury bills and other cash equivalents,

and another $20 billion in miscellaneous fixed-income instruments. We consider a portion of that stash to be

untouchable, having pledged to always hold at least $20 billion in cash equivalents to guard against external calamities.

We have also promised to avoid any activities that could threaten our maintaining that buffer.

Berkshire will forever remain a financial fortress. In managing, I will make expensive mistakes of

commission and will also miss many opportunities, some of which should have been obvious to me. At times, our

stock will tumble as investors flee from equities. But I will never risk getting caught short of cash.

In the years ahead, we hope to move much of our excess liquidity into businesses that Berkshire will

permanently own. The immediate prospects for that, however, are not good: Prices are sky-high for businesses

possessing decent long-term prospects.

That disappointing reality means that 2019 will likely see us again expanding our holdings of marketable

equities. We continue, nevertheless, to hope for an elephant-sized acquisition. Even at our ages of 88 and 95 – I’m the

young one – that prospect is what causes my heart and Charlie’s to beat faster. (Just writing about the possibility of a

huge purchase has caused my pulse rate to soar.)

My expectation of more stock purchases is not a market call. Charlie and I have no idea as to how stocks will

behave next week or next year. Predictions of that sort have never been a part of our activities. Our thinking, rather,

is focused on calculating whether a portion of an attractive business is worth more than its market price.

I believe Berkshire’s intrinsic value can be approximated by summing the values of our four asset-laden

groves and then subtracting an appropriate amount for taxes eventually payable on the sale of marketable securities.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

You may ask whether an allowance should not also be made for the major tax costs Berkshire would incur if

we were to sell certain of our wholly-owned businesses. Forget that thought: It would be foolish for us to sell any of

our wonderful companies even if no tax would be payable on its sale. Truly good businesses are exceptionally hard to

find. Selling any you are lucky enough to own makes no sense at all.

The interest cost on all of our debt has been deducted as an expense in calculating the earnings at Berkshire’s

non-insurance businesses. Beyond that, much of our ownership of the first four groves is financed by funds generated

from Berkshire’s fifth grove – a collection of exceptional insurance companies. We call those funds “float,” a source

of financing that we expect to be cost-free – or maybe even better than that – over time. We will explain the

characteristics of float later in this letter.

Finally, a point of key and lasting importance: Berkshire’s value is maximized by our having assembled the

five groves into a single entity. This arrangement allows us to seamlessly and objectively allocate major amounts of

capital, eliminate enterprise risk, avoid insularity, fund assets at exceptionally low cost, occasionally take advantage

of tax efficiencies, and minimize overhead.

At Berkshire, the whole is greater – considerably greater – than the sum of the parts.

6

�

Repurchases and Reporting

Earlier I mentioned that Berkshire will from time to time be repurchasing its own stock. Assuming that we

buy at a discount to Berkshire’s intrinsic value – which certainly will be our intention – repurchases will benefit both

those shareholders leaving the company and those who stay.

True, the upside from repurchases is very slight for those who are leaving. That’s because careful buying by

us will minimize any impact on Berkshire’s stock price. Nevertheless, there is some benefit to sellers in having an

extra buyer in the market.

For continuing shareholders, the advantage is obvious: If the market prices a departing partner’s interest at,

say, 90¢ on the dollar, continuing shareholders reap an increase in per-share intrinsic value with every repurchase by

the company. Obviously, repurchases should be price-sensitive: Blindly buying an overpriced stock is value-

destructive, a fact lost on many promotional or ever-optimistic CEOs.

When a company says that it contemplates repurchases, it’s vital that all shareholder-partners be given the

information they need to make an intelligent estimate of value. Providing that information is what Charlie and I try to

do in this report. We do not want a partner to sell shares back to the company because he or she has been misled or

inadequately informed.

Some sellers, however, may disagree with our calculation of value and others may have found investments

that they consider more attractive than Berkshire shares. Some of that second group will be right: There are

unquestionably many stocks that will deliver far greater gains than ours.

In addition, certain shareholders will simply decide it’s time for them or their families to become net

consumers rather than continuing to build capital. Charlie and I have no current interest in joining that group. Perhaps

we will become big spenders in our old age.

For 54 years our managerial decisions at Berkshire have been made from the viewpoint of the shareholders

who are staying, not those who are leaving. Consequently, Charlie and I have never focused on current-quarter results.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Berkshire, in fact, may be the only company in the Fortune 500 that does not prepare monthly earnings reports

or balance sheets. I, of course, regularly view the monthly financial reports of most subsidiaries. But Charlie and I

learn of Berkshire’s overall earnings and financial position only on a quarterly basis.

Furthermore, Berkshire has no company-wide budget (though many of our subsidiaries find one useful). Our

lack of such an instrument means that the parent company has never had a quarterly “number” to hit. Shunning the

use of this bogey sends an important message to our many managers, reinforcing the culture we prize.

Over the years, Charlie and I have seen all sorts of bad corporate behavior, both accounting and operational,

induced by the desire of management to meet Wall Street expectations. What starts as an “innocent” fudge in order to

not disappoint “the Street” – say, trade-loading at quarter-end, turning a blind eye to rising insurance losses, or drawing

down a “cookie-jar” reserve – can become the first step toward full-fledged fraud. Playing with the numbers “just this

once” may well be the CEO’s intent; it’s seldom the end result. And if it’s okay for the boss to cheat a little, it’s easy

for subordinates to rationalize similar behavior.

At Berkshire, our audience is neither analysts nor commentators: Charlie and I are working for our

shareholder-partners. The numbers that flow up to us will be the ones we send on to you.

7

�

Non-Insurance Operations – From Lollipops to Locomotives

Let’s now look further at Berkshire’s most valuable grove – our collection of non-insurance businesses –

keeping in mind that we do not wish to unnecessarily hand our competitors information that might be useful to them.

Additional details about individual operations can be found on pages K-5 – K-22 and pages K-40 – K-51.

Viewed as a group, these businesses earned pre-tax income in 2018 of $20.8 billion, a 24% increase over

2017. Acquisitions we made in 2018 delivered only a trivial amount of that gain.

I will stick with pre-tax figures in this discussion. But our after-tax gain in 2018 from these businesses was

far greater – 47% – thanks in large part to the cut in the corporate tax rate that became effective at the beginning of

that year. Let’s look at why the impact was so dramatic.

Begin with an economic reality: Like it or not, the U.S. Government “owns” an interest in Berkshire’s

earnings of a size determined by Congress. In effect, our country’s Treasury Department holds a special class of our

stock – call this holding the AA shares – that receives large “dividends” (that is, tax payments) from Berkshire. In

2017, as in many years before, the corporate tax rate was 35%, which meant that the Treasury was doing very well

with its AA shares. Indeed, the Treasury’s “stock,” which was paying nothing when we took over in 1965, had evolved

into a holding that delivered billions of dollars annually to the federal government.

Last year, however, 40% of the government’s “ownership” (14/35ths) was returned to Berkshire – free of

charge – when the corporate tax rate was reduced to 21%. Consequently, our “A” and “B” shareholders received a

major boost in the earnings attributable to their shares.

This happening materially increased the intrinsic value of the Berkshire shares you and I own. The same

dynamic, moreover, enhanced the intrinsic value of almost all of the stocks Berkshire holds.

Those are the headlines. But there are other factors to consider that tempered our gain. For example, the tax

benefits garnered by our large utility operation get passed along to its customers. Meanwhile, the tax rate applicable

to the substantial dividends we receive from domestic corporations is little changed at about 13%. (This lower rate has

long been logical because our investees have already paid tax on the earnings that they pay to us.) Overall, however,

the new law made our businesses and the stocks we own considerably more valuable.

Which suggests that we return to the performance of our non-insurance businesses. Our two towering redwoods

in this grove are BNSF and Berkshire Hathaway Energy (90.9% owned). Combined, they earned $9.3 billion before tax

last year, up 6% from 2017. You can read more about these businesses on pages K-5 – K-10 and pages K-40 – K-45.

Our next five non-insurance subsidiaries, as ranked by earnings (but presented here alphabetically), Clayton

Homes, International Metalworking, Lubrizol, Marmon and Precision Castparts, had aggregate pre-tax income in 2018

of $6.4 billion, up from the $5.5 billion these companies earned in 2017.

The next five, similarly ranked and listed (Forest River, Johns Manville, MiTek, Shaw and TTI) earned $2.4

billion pre-tax last year, up from $2.1 billion in 2017.

The remaining non-insurance businesses that Berkshire owns – and there are many – had pre-tax income of

$3.6 billion in 2018 vs. $3.3 billion in 2017.

8

�

Insurance, “Float,” and the Funding of Berkshire

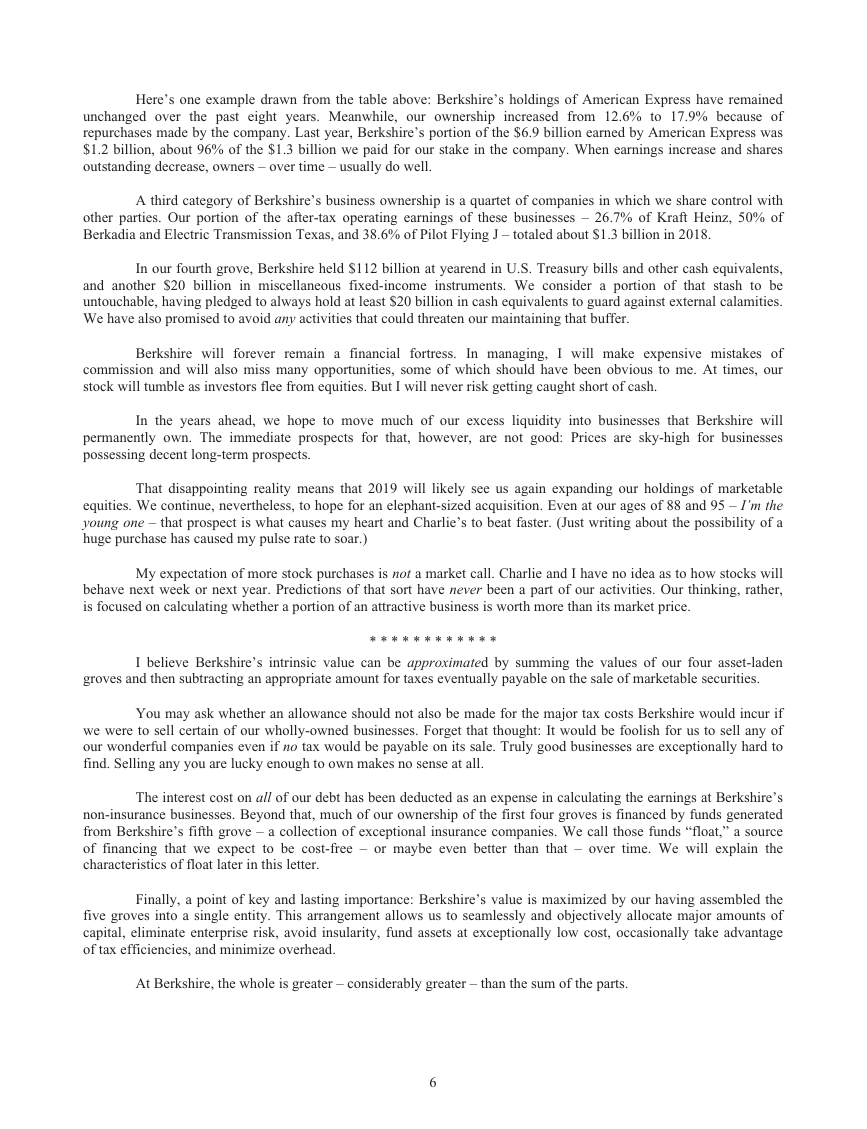

Our property/casualty (“P/C”) insurance business – our fifth grove – has been the engine propelling

Berkshire’s growth since 1967, the year we acquired National Indemnity and its sister company, National Fire &

Marine, for $8.6 million. Today, National Indemnity is the largest property/casualty company in the world as measured

by net worth.

One reason we were attracted to the P/C business was the industry’s business model: P/C insurers receive

premiums upfront and pay claims later. In extreme cases, such as claims arising from exposure to asbestos, or severe

workplace accidents, payments can stretch over many decades.

This collect-now, pay-later model leaves P/C companies holding large sums – money we call “float” – that

will eventually go to others. Meanwhile, insurers get to invest this float for their own benefit. Though individual

policies and claims come and go, the amount of float an insurer holds usually remains fairly stable in relation to

premium volume. Consequently, as our business grows, so does our float. And how it has grown, as the following

table shows:

Year

1970

1980

1990

2000

2010

2018

Float (in millions)*

$

39

237

1,632

27,871

65,832

122,732

*

Includes float arising from life, annuity and health insurance businesses.

We may in time experience a decline in float. If so, the decline will be very gradual – at the outside no more

than 3% in any year. The nature of our insurance contracts is such that we can never be subject to immediate or near-

term demands for sums that are of significance to our cash resources. That structure is by design and is a key

component in the unequaled financial strength of our insurance companies. That strength will never be compromised.

If our premiums exceed the total of our expenses and eventual losses, our insurance operation registers an

underwriting profit that adds to the investment income the float produces. When such a profit is earned, we enjoy the

use of free money – and, better yet, get paid for holding it.

Unfortunately, the wish of all insurers to achieve this happy result creates intense competition, so vigorous

indeed that it sometimes causes the P/C industry as a whole to operate at a significant underwriting loss. That loss, in

effect, is what the industry pays to hold its float. Competitive dynamics almost guarantee that the insurance industry,

despite the float income all its companies enjoy, will continue its dismal record of earning subnormal returns on

tangible net worth as compared to other American businesses.

Nevertheless, I like our own prospects. Berkshire’s unrivaled financial strength allows us far more flexibility

in investing our float than that generally available to P/C companies. The many alternatives available to us are always

an advantage and occasionally offer major opportunities. When other insurers are constrained, our choices expand.

Moreover, our P/C companies have an excellent underwriting record. Berkshire has now operated at an

underwriting profit for 15 of the past 16 years, the exception being 2017, when our pre-tax loss was $3.2 billion. For

the entire 16-year span, our pre-tax gain totaled $27 billion, of which $2 billion was recorded in 2018.

9

�