To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

Our gain in net worth during 1986 was $492.5 million, or

26.1%. Over the last 22 years (that is, since present management

took over), our per-share book value has grown from $19.46 to

$2,073.06, or 23.3% compounded annually. Both the numerator and

denominator are important in the per-share book value

calculation: during the 22-year period our corporate net worth

has increased 10,600% while shares outstanding have increased

less than 1%.

In past reports I have noted that book value at most

companies differs widely from intrinsic business value - the

number that really counts for owners. In our own case, however,

book value has served for more than a decade as a reasonable if

somewhat conservative proxy for business value. That is, our

business value has moderately exceeded our book value, with the

ratio between the two remaining fairly steady.

The good news is that in 1986 our percentage gain in

business value probably exceeded the book value gain. I say

"probably" because business value is a soft number: in our own

case, two equally well-informed observers might make judgments

more than 10% apart.

A large measure of our improvement in business value

relative to book value reflects the outstanding performance of

key managers at our major operating businesses. These managers -

the Blumkins, Mike Goldberg, the Heldmans, Chuck Huggins, Stan

Lipsey, and Ralph Schey - have over the years improved the

earnings of their businesses dramatically while, except in the

case of insurance, utilizing little additional capital. This

accomplishment builds economic value, or "Goodwill," that does

not show up in the net worth figure on our balance sheet, nor in

our per-share book value. In 1986 this unrecorded gain was

substantial.

So much for the good news. The bad news is that my

performance did not match that of our managers. While they were

doing a superb job in running our businesses, I was unable to

skillfully deploy much of the capital they generated.

Charlie Munger, our Vice Chairman, and I really have only

two jobs. One is to attract and keep outstanding managers to run

our various operations. This hasn’t been all that difficult.

Usually the managers came with the companies we bought, having

demonstrated their talents throughout careers that spanned a wide

variety of business circumstances. They were managerial stars

long before they knew us, and our main contribution has been to

not get in their way. This approach seems elementary: if my job

were to manage a golf team - and if Jack Nicklaus or Arnold

Palmer were willing to play for me - neither would get a lot of

directives from me about how to swing.

Some of our key managers are independently wealthy (we hope

they all become so), but that poses no threat to their continued

interest: they work because they love what they do and relish the

thrill of outstanding performance. They unfailingly think like

owners (the highest compliment we can pay a manager) and find all

aspects of their business absorbing.

(Our prototype for occupational fervor is the Catholic

tailor who used his small savings of many years to finance a

pilgrimage to the Vatican. When he returned, his parish held a

B

E

R

K

S

H

I

R

E

H

A

T

H

A

W

A

Y

I

N

C

.

�

special meeting to get his first-hand account of the Pope. "Tell

us," said the eager faithful, "just what sort of fellow is he?"

Our hero wasted no words: "He’s a forty-four, medium.")

Charlie and I know that the right players will make almost

any team manager look good. We subscribe to the philosophy of

Ogilvy & Mather’s founding genius, David Ogilvy: "If each of us

hires people who are smaller than we are, we shall become a

company of dwarfs. But, if each of us hires people who are

bigger than we are, we shall become a company of giants."

A by-product of our managerial style is the ability it gives

us to easily expand Berkshire’s activities. We’ve read

management treatises that specify exactly how many people should

report to any one executive, but they make little sense to us.

When you have able managers of high character running businesses

about which they are passionate, you can have a dozen or more

reporting to you and still have time for an afternoon nap.

Conversely, if you have even one person reporting to you who is

deceitful, inept or uninterested, you will find yourself with

more than you can handle. Charlie and I could work with double

the number of managers we now have, so long as they had the rare

qualities of the present ones.

We intend to continue our practice of working only with

people whom we like and admire. This policy not only maximizes

our chances for good results, it also ensures us an

extraordinarily good time. On the other hand, working with

people who cause your stomach to churn seems much like marrying

for money - probably a bad idea under any circumstances, but

absolute madness if you are already rich.

The second job Charlie and I must handle is the allocation

of capital, which at Berkshire is a considerably more important

challenge than at most companies. Three factors make that so: we

earn more money than average; we retain all that we earn; and, we

are fortunate to have operations that, for the most part, require

little incremental capital to remain competitive and to grow.

Obviously, the future results of a business earning 23% annually

and retaining it all are far more affected by today’s capital

allocations than are the results of a business earning 10% and

distributing half of that to shareholders. If our retained

earnings - and those of our major investees, GEICO and Capital

Cities/ABC, Inc. - are employed in an unproductive manner, the

economics of Berkshire will deteriorate very quickly. In a

company adding only, say, 5% to net worth annually, capital-

allocation decisions, though still important, will change the

company’s economics far more slowly.

Capital allocation at Berkshire was tough work in 1986. We

did make one business acquisition - The Fechheimer Bros.

Company, which we will discuss in a later section. Fechheimer is

a company with excellent economics, run by exactly the kind of

people with whom we enjoy being associated. But it is relatively

small, utilizing only about 2% of Berkshire’s net worth.

Meanwhile, we had no new ideas in the marketable equities

field, an area in which once, only a few years ago, we could

readily employ large sums in outstanding businesses at very

reasonable prices. So our main capital allocation moves in 1986

were to pay off debt and stockpile funds. Neither is a fate

worse than death, but they do not inspire us to do handsprings

either. If Charlie and I were to draw blanks for a few years in

our capital-allocation endeavors, Berkshire’s rate of growth

would slow significantly.

We will continue to look for operating businesses that meet

our tests and, with luck, will acquire such a business every

couple of years. But an acquisition will have to be large if it

�

is to help our performance materially. Under current stock

market conditions, we have little hope of finding equities to buy

for our insurance companies. Markets will change significantly -

you can be sure of that and some day we will again get our turn

at bat. However, we haven’t the faintest idea when that might

happen.

It can’t be said too often (although I’m sure you feel I’ve

tried) that, even under favorable conditions, our returns are

certain to drop substantially because of our enlarged size. We

have told you that we hope to average a return of 15% on equity

and we maintain that hope, despite some negative tax law changes

described in a later section of this report. If we are to

achieve this rate of return, our net worth must increase $7.2

billion in the next ten years. A gain of that magnitude will be

possible only if, before too long, we come up with a few very big

(and good) ideas. Charlie and I can’t promise results, but we do

promise you that we will keep our efforts focused on our goals.

Sources of Reported Earnings

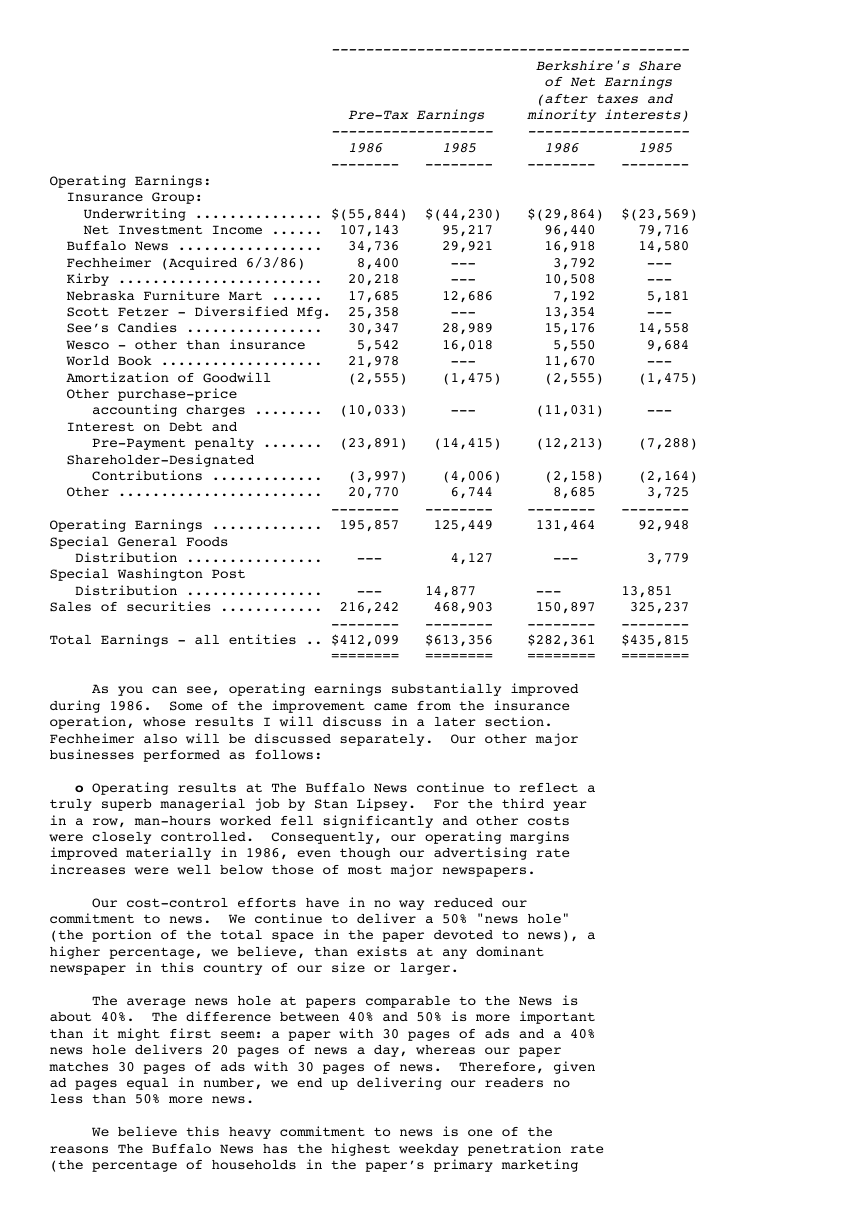

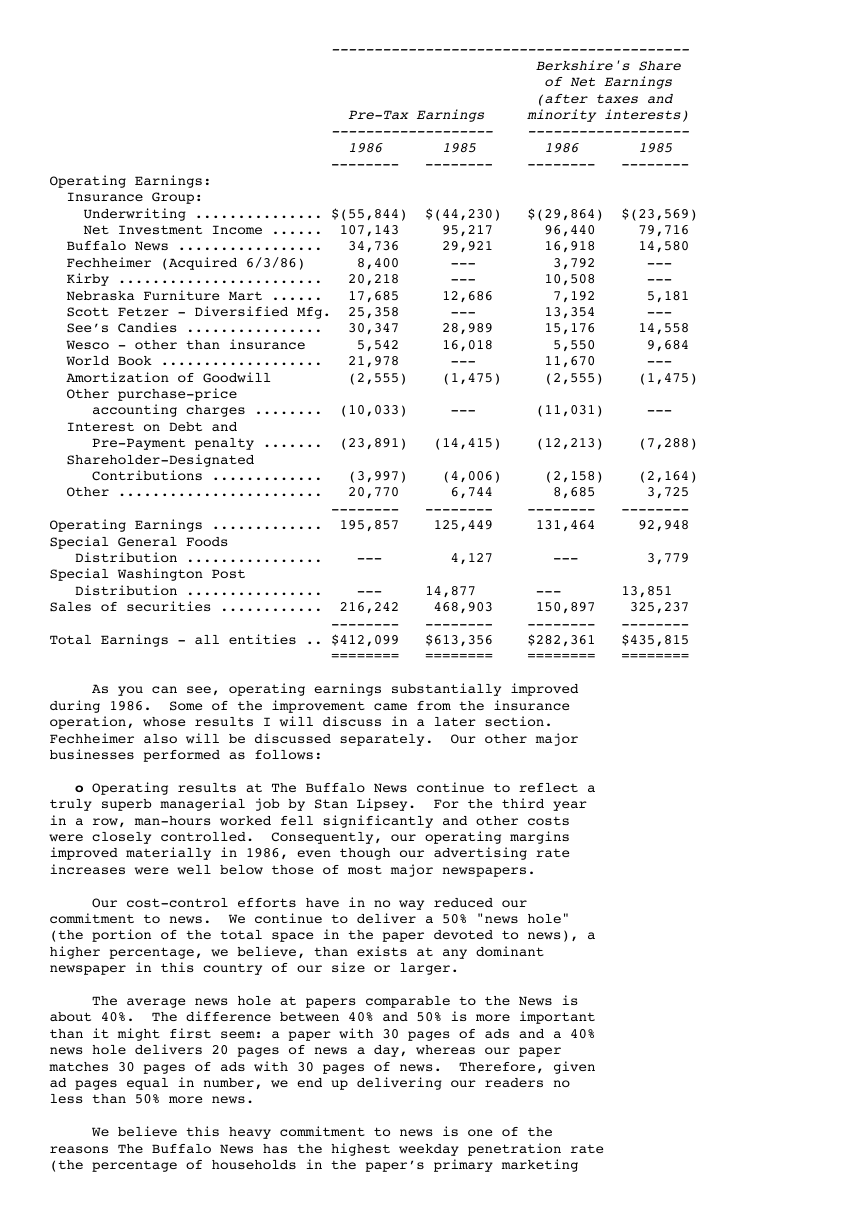

The table on the next page shows the major sources of

Berkshire’s reported earnings. This table differs in several

ways from the one presented last year. We have added four new

lines of business because of the Scott Fetzer and Fechheimer

acquisitions. In the case of Scott Fetzer, the two major units

acquired were World Book and Kirby, and each is presented

separately. Fourteen other businesses of Scott Fetzer are

aggregated in Scott Fetzer - Diversified Manufacturing. SF

Financial Group, a credit company holding both World Book and

Kirby receivables, is included in "Other." This year, because

Berkshire is so much larger, we also have eliminated separate

reporting for several of our smaller businesses.

In the table, amortization of Goodwill is not charged

against the specific businesses but, for reasons outlined in the

Appendix to my letter in the 1983 Annual Report, is aggregated as

a separate item. (A Compendium of earlier letters, including the

Goodwill discussion, is available upon request.) Both the Scott

Fetzer and Fechheimer acquisitions created accounting Goodwill,

which is why the amortization charge for Goodwill increased in

1986.

Additionally, the Scott Fetzer acquisition required other

major purchase-price accounting adjustments, as prescribed by

generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). The GAAP

figures, of course, are the ones used in our consolidated

financial statements. But, in our view, the GAAP figures are not

necessarily the most useful ones for investors or managers.

Therefore, the figures shown for specific operating units are

earnings before purchase-price adjustments are taken into

account. In effect, these are the earnings that would have been

reported by the businesses if we had not purchased them.

A discussion of our reasons for preferring this form of

presentation is in the Appendix to this letter. This Appendix

will never substitute for a steamy novel and definitely is not

required reading. However, I know that among our 6,000

shareholders there are those who are thrilled by my essays on

accounting - and I hope that both of you enjoy the Appendix.

In the Business Segment Data on pages 41-43 and in the

Management’s Discussion section on pages 45-49, you will find

much additional information about our businesses. I urge you to

read those sections, as well as Charlie Munger’s letter to Wesco

shareholders, describing the various businesses of that

subsidiary, which starts on page 50.

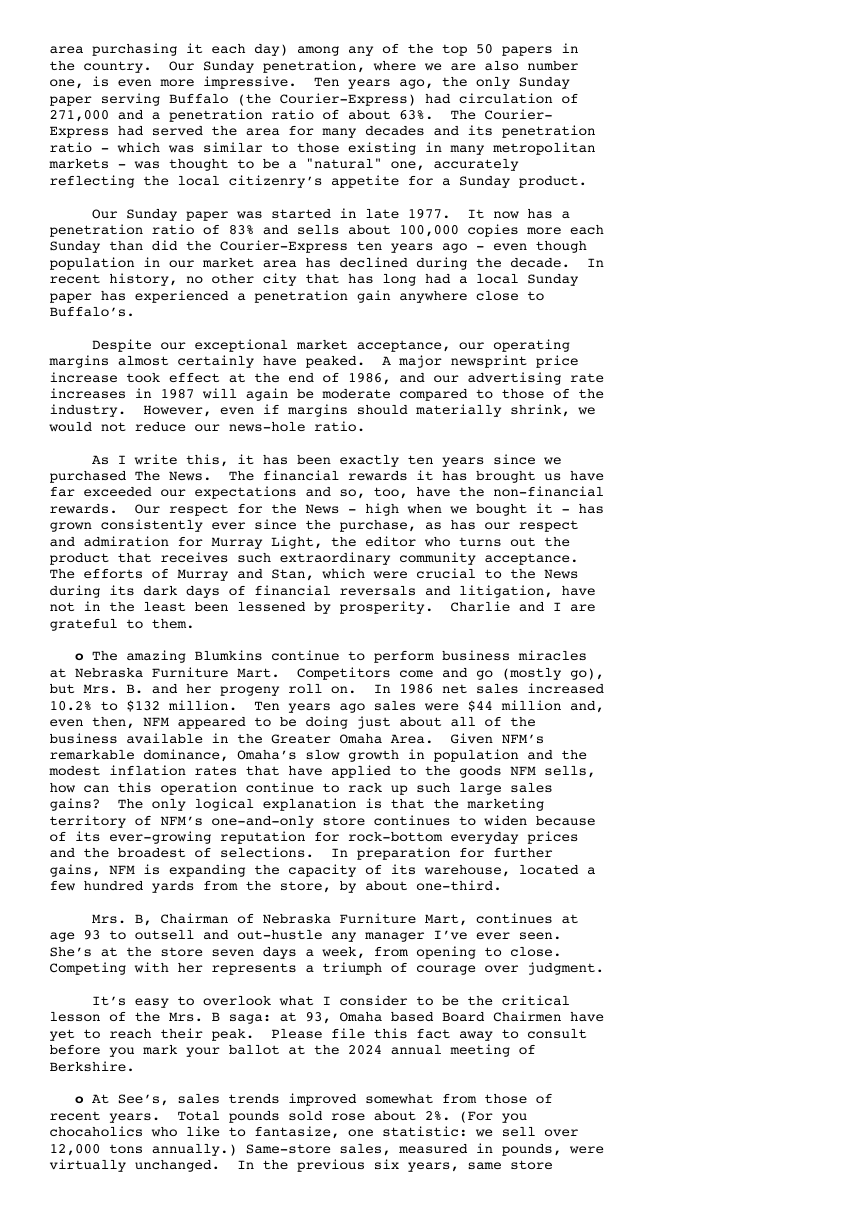

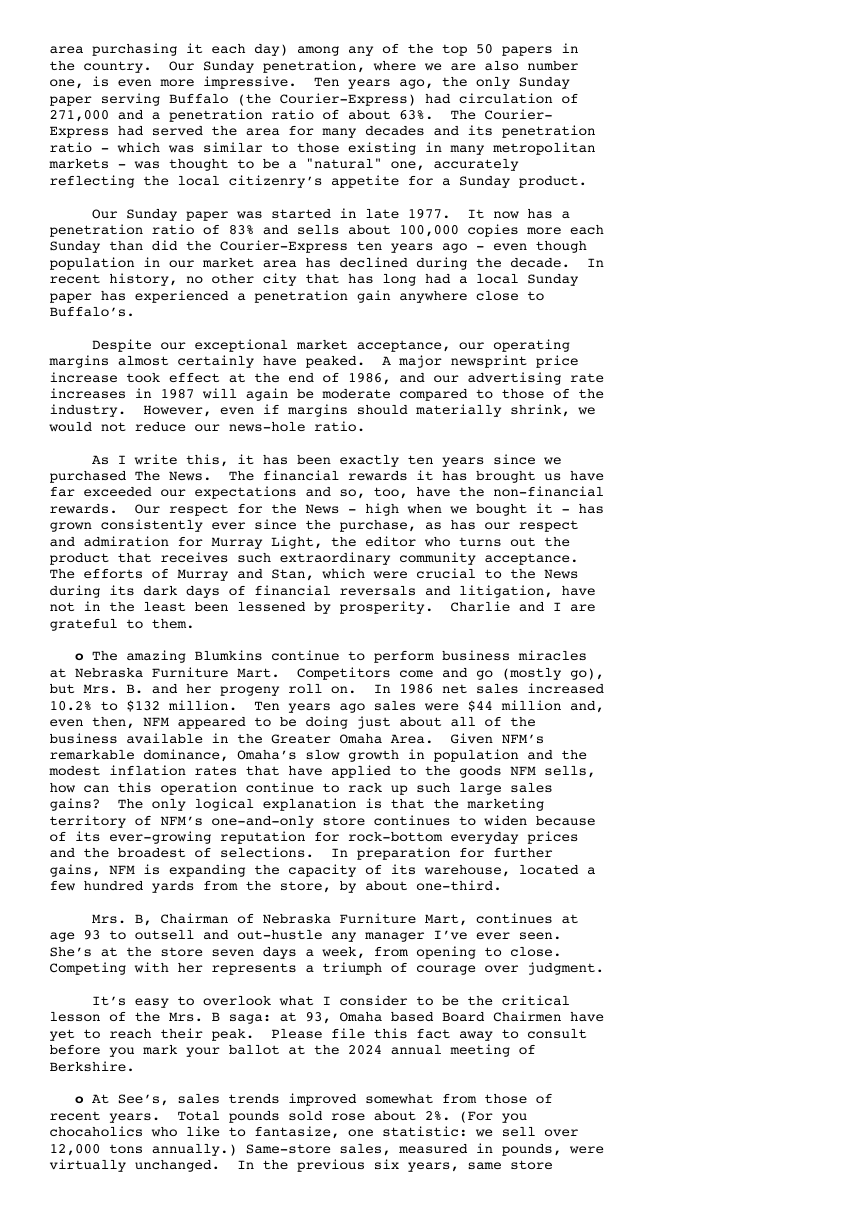

(000s omitted)

�

------------------------------------------

Berkshire's Share

of Net Earnings

(after taxes and

Pre-Tax Earnings minority interests)

------------------- -------------------

1986 1985 1986 1985

-------- -------- -------- --------

Operating Earnings:

Insurance Group:

Underwriting ............... $(55,844) $(44,230) $(29,864) $(23,569)

Net Investment Income ...... 107,143 95,217 96,440 79,716

Buffalo News ................. 34,736 29,921 16,918 14,580

Fechheimer (Acquired 6/3/86) 8,400 --- 3,792 ---

Kirby ........................ 20,218 --- 10,508 ---

Nebraska Furniture Mart ...... 17,685 12,686 7,192 5,181

Scott Fetzer - Diversified Mfg. 25,358 --- 13,354 ---

See’s Candies ................ 30,347 28,989 15,176 14,558

Wesco - other than insurance 5,542 16,018 5,550 9,684

World Book ................... 21,978 --- 11,670 ---

Amortization of Goodwill (2,555) (1,475) (2,555) (1,475)

Other purchase-price

accounting charges ........ (10,033) --- (11,031) ---

Interest on Debt and

Pre-Payment penalty ....... (23,891) (14,415) (12,213) (7,288)

Shareholder-Designated

Contributions ............. (3,997) (4,006) (2,158) (2,164)

Other ........................ 20,770 6,744 8,685 3,725

-------- -------- -------- --------

Operating Earnings ............. 195,857 125,449 131,464 92,948

Special General Foods

Distribution ................ --- 4,127 --- 3,779

Special Washington Post

Distribution ................ --- 14,877 --- 13,851

Sales of securities ............ 216,242 468,903 150,897 325,237

-------- -------- -------- --------

Total Earnings - all entities .. $412,099 $613,356 $282,361 $435,815

======== ======== ======== ========

As you can see, operating earnings substantially improved

during 1986. Some of the improvement came from the insurance

operation, whose results I will discuss in a later section.

Fechheimer also will be discussed separately. Our other major

businesses performed as follows:

o Operating results at The Buffalo News continue to reflect a

truly superb managerial job by Stan Lipsey. For the third year

in a row, man-hours worked fell significantly and other costs

were closely controlled. Consequently, our operating margins

improved materially in 1986, even though our advertising rate

increases were well below those of most major newspapers.

Our cost-control efforts have in no way reduced our

commitment to news. We continue to deliver a 50% "news hole"

(the portion of the total space in the paper devoted to news), a

higher percentage, we believe, than exists at any dominant

newspaper in this country of our size or larger.

The average news hole at papers comparable to the News is

about 40%. The difference between 40% and 50% is more important

than it might first seem: a paper with 30 pages of ads and a 40%

news hole delivers 20 pages of news a day, whereas our paper

matches 30 pages of ads with 30 pages of news. Therefore, given

ad pages equal in number, we end up delivering our readers no

less than 50% more news.

We believe this heavy commitment to news is one of the

reasons The Buffalo News has the highest weekday penetration rate

(the percentage of households in the paper’s primary marketing

�

area purchasing it each day) among any of the top 50 papers in

the country. Our Sunday penetration, where we are also number

one, is even more impressive. Ten years ago, the only Sunday

paper serving Buffalo (the Courier-Express) had circulation of

271,000 and a penetration ratio of about 63%. The Courier-

Express had served the area for many decades and its penetration

ratio - which was similar to those existing in many metropolitan

markets - was thought to be a "natural" one, accurately

reflecting the local citizenry’s appetite for a Sunday product.

Our Sunday paper was started in late 1977. It now has a

penetration ratio of 83% and sells about 100,000 copies more each

Sunday than did the Courier-Express ten years ago - even though

population in our market area has declined during the decade. In

recent history, no other city that has long had a local Sunday

paper has experienced a penetration gain anywhere close to

Buffalo’s.

Despite our exceptional market acceptance, our operating

margins almost certainly have peaked. A major newsprint price

increase took effect at the end of 1986, and our advertising rate

increases in 1987 will again be moderate compared to those of the

industry. However, even if margins should materially shrink, we

would not reduce our news-hole ratio.

As I write this, it has been exactly ten years since we

purchased The News. The financial rewards it has brought us have

far exceeded our expectations and so, too, have the non-financial

rewards. Our respect for the News - high when we bought it - has

grown consistently ever since the purchase, as has our respect

and admiration for Murray Light, the editor who turns out the

product that receives such extraordinary community acceptance.

The efforts of Murray and Stan, which were crucial to the News

during its dark days of financial reversals and litigation, have

not in the least been lessened by prosperity. Charlie and I are

grateful to them.

o The amazing Blumkins continue to perform business miracles

at Nebraska Furniture Mart. Competitors come and go (mostly go),

but Mrs. B. and her progeny roll on. In 1986 net sales increased

10.2% to $132 million. Ten years ago sales were $44 million and,

even then, NFM appeared to be doing just about all of the

business available in the Greater Omaha Area. Given NFM’s

remarkable dominance, Omaha’s slow growth in population and the

modest inflation rates that have applied to the goods NFM sells,

how can this operation continue to rack up such large sales

gains? The only logical explanation is that the marketing

territory of NFM’s one-and-only store continues to widen because

of its ever-growing reputation for rock-bottom everyday prices

and the broadest of selections. In preparation for further

gains, NFM is expanding the capacity of its warehouse, located a

few hundred yards from the store, by about one-third.

Mrs. B, Chairman of Nebraska Furniture Mart, continues at

age 93 to outsell and out-hustle any manager I’ve ever seen.

She’s at the store seven days a week, from opening to close.

Competing with her represents a triumph of courage over judgment.

It’s easy to overlook what I consider to be the critical

lesson of the Mrs. B saga: at 93, Omaha based Board Chairmen have

yet to reach their peak. Please file this fact away to consult

before you mark your ballot at the 2024 annual meeting of

Berkshire.

o At See’s, sales trends improved somewhat from those of

recent years. Total pounds sold rose about 2%. (For you

chocaholics who like to fantasize, one statistic: we sell over

12,000 tons annually.) Same-store sales, measured in pounds, were

virtually unchanged. In the previous six years, same store

�

poundage fell, and we gained or maintained poundage volume only

by adding stores. But a particularly strong Christmas season in

1986 stemmed the decline. By stabilizing same-store volume and

making a major effort to control costs, See’s was able to

maintain its excellent profit margin in 1986 though it put

through only minimal price increases. We have Chuck Huggins, our

long-time manager at See’s, to thank for this significant

achievement.

See’s has a one-of-a-kind product "personality" produced by

a combination of its candy’s delicious taste and moderate price,

the company’s total control of the distribution process, and the

exceptional service provided by store employees. Chuck

rightfully measures his success by the satisfaction of our

customers, and his attitude permeates the organization. Few

major retailing companies have been able to sustain such a

customer-oriented spirit, and we owe Chuck a great deal for

keeping it alive and well at See’s.

See’s profits should stay at about their present level. We

will continue to increase prices very modestly, merely matching

prospective cost increases.

o World Book is the largest of 17 Scott Fetzer operations

that joined Berkshire at the beginning of 1986. Last year I

reported to you enthusiastically about the businesses of Scott

Fetzer and about Ralph Schey, its manager. A year’s experience

has added to my enthusiasm for both. Ralph is a superb

businessman and a straight shooter. He also brings exceptional

versatility and energy to his job: despite the wide array of

businesses that he manages, he is on top of the operations,

opportunities and problems of each. And, like our other

managers, Ralph is a real pleasure to work with. Our good

fortune continues.

World Book’s unit volume increased for the fourth

consecutive year, with encyclopedia sales up 7% over 1985 and 45%

over 1982. Childcraft’s unit sales also grew significantly.

World Book continues to dominate the U.S. direct-sales

encyclopedia market - and for good reasons. Extraordinarily

well-edited and priced at under 5 cents per page, these books are

a bargain for youngster and adult alike. You may find one

editing technique interesting: World Book ranks over 44,000 words

by difficulty. Longer entries in the encyclopedia include only

the most easily comprehended words in the opening sections, with

the difficulty of the material gradually escalating as the

exposition proceeds. As a result, youngsters can easily and

profitably read to the point at which subject matter gets too

difficult, instead of immediately having to deal with a

discussion that mixes up words requiring college-level

comprehension with others of fourth-grade level.

Selling World Book is a calling. Over one-half of our

active salespeople are teachers or former teachers, and another

5% have had experience as librarians. They correctly think of

themselves as educators, and they do a terrific job. If you

don’t have a World Book set in your house, I recommend one.

o Kirby likewise recorded its fourth straight year of unit

volume gains. Worldwide, unit sales grew 4% from 1985 and 33%

from 1982. While the Kirby product is more expensive than most

cleaners, it performs in a manner that leaves cheaper units far

behind ("in the dust," so to speak). Many 30- and 40-year-old

Kirby cleaners are still in active duty. If you want the best,

you buy a Kirby.

Some companies that historically have had great success in

direct sales have stumbled in recent years. Certainly the era of

�

the working woman has created new challenges for direct sales

organizations. So far, the record shows that both Kirby and

World Book have responded most successfully.

The businesses described above, along with the insurance

operation and Fechheimer, constitute our major business units.

The brevity of our descriptions is in no way meant to diminish

the importance of these businesses to us. All have been

discussed in past annual reports and, because of the tendency of

Berkshire owners to stay in the fold (about 98% of the stock at

the end of each year is owned by people who were owners at the

start of the year), we want to avoid undue repetition of basic

facts. You can be sure that we will immediately report to you in

detail if the underlying economics or competitive position of any

of these businesses should materially change. In general, the

businesses described in this section can be characterized as

having very strong market positions, very high returns on capital

employed, and the best of operating managements.

The Fechheimer Bros. Co.

Every year in Berkshire’s annual report I include a

description of the kind of business that we would like to buy.

This "ad" paid off in 1986.

On January 15th of last year I received a letter from Bob

Heldman of Cincinnati, a shareholder for many years and also

Chairman of Fechheimer Bros. Until I read the letter, however, I

did not know of either Bob or Fechheimer. Bob wrote that he ran

a company that met our tests and suggested that we get together,

which we did in Omaha after their results for 1985 were compiled.

He filled me in on a little history: Fechheimer, a uniform

manufacturing and distribution business, began operations in

1842. Warren Heldman, Bob’s father, became involved in the

business in 1941 and his sons, Bob and George (now President),

along with their sons, subsequently joined the company. Under

the Heldmans’ management, the business was highly successful.

In 1981 Fechheimer was sold to a group of venture

capitalists in a leveraged buy out (an LBO), with management

retaining an equity interest. The new company, as is the case

with all LBOS, started with an exceptionally high debt/equity

ratio. After the buy out, however, operations continued to be

very successful. So by the start of last year debt had been paid

down substantially and the value of the equity had increased

dramatically. For a variety of reasons, the venture capitalists

wished to sell and Bob, having dutifully read Berkshire’s annual

reports, thought of us.

Fechheimer is exactly the sort of business we like to buy.

Its economic record is superb; its managers are talented, high-

grade, and love what they do; and the Heldman family wanted to

continue its financial interest in partnership with us.

Therefore, we quickly purchased about 84% of the stock for a

price that was based upon a $55 million valuation for the entire

business.

The circumstances of this acquisition were similar to those

prevailing in our purchase of Nebraska Furniture Mart: most of

the shares were held by people who wished to employ funds

elsewhere; family members who enjoyed running their business

wanted to continue both as owners and managers; several

generations of the family were active in the business, providing

management for as far as the eye can see; and the managing family

wanted a purchaser who would not re-sell, regardless of price,

and who would let the business be run in the future as it had

been in the past. Both Fechheimer and NFM were right for us, and

we were right for them.

�

You may be amused to know that neither Charlie nor I have

been to Cincinnati, headquarters for Fechheimer, to see their

operation. (And, incidentally, it works both ways: Chuck Huggins,

who has been running See’s for 15 years, has never been to

Omaha.) If our success were to depend upon insights we developed

through plant inspections, Berkshire would be in big trouble.

Rather, in considering an acquisition, we attempt to evaluate the

economic characteristics of the business - its competitive

strengths and weaknesses - and the quality of the people we will

be joining. Fechheimer was a standout in both respects. In

addition to Bob and George Heldman, who are in their mid-60s -

spring chickens by our standards - there are three members of the

next generation, Gary, Roger and Fred, to insure continuity.

As a prototype for acquisitions, Fechheimer has only one

drawback: size. We hope our next acquisition is at least several

times as large but a carbon copy in all other respects. Our

threshold for minimum annual after-tax earnings of potential

acquisitions has been moved up to $10 million from the $5 million

level that prevailed when Bob wrote to me.

Flushed with success, we repeat our ad. If you have a

business that fits, call me or, preferably, write.

Here’s what we’re looking for:

(1) large purchases (at least $10 million of after-tax

earnings),

(2) demonstrated consistent earning power (future

projections are of little interest to us, nor are

"turn-around" situations),

(3) businesses earning good returns on equity while

employing little or no debt.

(4) management in place (we can’t supply it),

(5) simple businesses (if there’s lots of technology, we

won’t understand it),

(6) an offering price (we don’t want to waste our time

or that of the seller by talking, even preliminarily,

about a transaction when price is unknown).

We will not engage in unfriendly takeovers. We can promise

complete confidentiality and a very fast answer - customarily

within five minutes - as to whether we’re interested. We prefer

to buy for cash, but will consider issuing stock when we receive

as much in intrinsic business value as we give. Indeed,

following recent advances in the price of Berkshire stock,

transactions involving stock issuance may be quite feasible. We

invite potential sellers to check us out by contacting people

with whom we have done business in the past. For the right

business - and the right people - we can provide a good home.

On the other hand, we frequently get approached about

acquisitions that don’t come close to meeting our tests: new

ventures, turnarounds, auction-like sales, and the ever-popular

(among brokers) "I’m-sure-something-will-work-out-if-you-people-

get-to-know-each-other." None of these attracts us in the least.

* * *

Besides being interested in the purchases of entire

businesses as described above, we are also interested in the

negotiated purchase of large, but not controlling, blocks of

stock, as in our Cap Cities purchase. Such purchases appeal to

us only when we are very comfortable with both the economics of

the business and the ability and integrity of the people running

the operation. We prefer large transactions: in the unusual case

we might do something as small as $50 million (or even smaller),

but our preference is for commitments many times that size.

�