March 3, 1983

To the Stockholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

Operating earnings of $31.5 million in 1982 amounted to only

9.8% of beginning equity capital (valuing securities at cost),

down from 15.2% in 1981 and far below our recent high of 19.4% in

1978. This decline largely resulted from:

(1) a significant deterioration in insurance underwriting

results;

(2) a considerable expansion of equity capital without a

corresponding growth in the businesses we operate

directly; and

(3) a continually-enlarging commitment of our resources to

investment in partially-owned, nonoperated businesses;

accounting rules dictate that a major part of our

pro-rata share of earnings from such businesses must be

excluded from Berkshire’s reported earnings.

It was only a few years ago that we told you that the

operating earnings/equity capital percentage, with proper

allowance for a few other variables, was the most important

yardstick of single-year managerial performance. While we still

believe this to be the case with the vast majority of companies,

we believe its utility in our own case has greatly diminished.

You should be suspicious of such an assertion. Yardsticks seldom

are discarded while yielding favorable readings. But when

results deteriorate, most managers favor disposition of the

yardstick rather than disposition of the manager.

To managers faced with such deterioration, a more flexible

measurement system often suggests itself: just shoot the arrow of

business performance into a blank canvas and then carefully draw

the bullseye around the implanted arrow. We generally believe in

pre-set, long-lived and small bullseyes. However, because of the

importance of item (3) above, further explained in the following

section, we believe our abandonment of the operating

earnings/equity capital bullseye to be warranted.

Non-Reported Ownership Earnings

The appended financial statements reflect “accounting”

earnings that generally include our proportionate share of

earnings from any underlying business in which our ownership is

at least 20%. Below the 20% ownership figure, however, only our

share of dividends paid by the underlying business units is

included in our accounting numbers; undistributed earnings of

such less-than-20%-owned businesses are totally ignored.

There are a few exceptions to this rule; e.g., we own about

35% of GEICO Corporation but, because we have assigned our voting

rights, the company is treated for accounting purposes as a less-

than-20% holding. Thus, dividends received from GEICO in 1982 of

$3.5 million after tax are the only item included in our

“accounting”earnings. An additional $23 million that represents

our share of GEICO’s undistributed operating earnings for 1982 is

totally excluded from our reported operating earnings. If GEICO

had earned less money in 1982 but had paid an additional $1

million in dividends, our reported earnings would have been

larger despite the poorer business results. Conversely, if GEICO

had earned an additional $100 million - and retained it all - our

reported earnings would have been unchanged. Clearly

“accounting” earnings can seriously misrepresent economic

reality.

We prefer a concept of “economic” earnings that includes all

undistributed earnings, regardless of ownership percentage. In

our view, the value to all owners of the retained earnings of a

business enterprise is determined by the effectiveness with which

those earnings are used - and not by the size of one’s ownership

percentage. If you have owned .01 of 1% of Berkshire during the

past decade, you have benefited economically in full measure from

your share of our retained earnings, no matter what your

accounting system. Proportionately, you have done just as well

as if you had owned the magic 20%. But if you have owned 100% of

a great many capital-intensive businesses during the decade,

retained earnings that were credited fully and with painstaking

precision to you under standard accounting methods have resulted

in minor or zero economic value. This is not a criticism of

accounting procedures. We would not like to have the job of

designing a better system. It’s simply to say that managers and

investors alike must understand that accounting numbers are the

beginning, not the end, of business valuation.

In most corporations, less-than-20% ownership positions are

unimportant (perhaps, in part, because they prevent maximization

of cherished reported earnings) and the distinction between

accounting and economic results we have just discussed matters

little. But in our own case, such positions are of very large

and growing importance. Their magnitude, we believe, is what

B

E

R

K

S

H

I

R

E

H

A

T

H

A

W

A

Y

I

N

C

.

�

makes our reported operating earnings figure of limited

significance.

In our 1981 annual report we predicted that our share of

undistributed earnings from four of our major non-controlled

holdings would aggregate over $35 million in 1982. With no

change in our holdings of three of these companies - GEICO,

General Foods and The Washington Post - and a considerable

increase in our ownership of the fourth, R. J. Reynolds

Industries, our share of undistributed 1982 operating earnings of

this group came to well over $40 million. This number - not

reflected at all in our earnings - is greater than our total

reported earnings, which include only the $14 million in

dividends received from these companies. And, of course, we have

a number of smaller ownership interests that, in aggregate, had

substantial additional undistributed earnings.

We attach real significance to the general magnitude of

these numbers, but we don’t believe they should be carried to ten

decimal places. Realization by Berkshire of such retained

earnings through improved market valuations is subject to very

substantial, but indeterminate, taxation. And while retained

earnings over the years, and in the aggregate, have translated

into at least equal market value for shareholders, the

translation has been both extraordinarily uneven among companies

and irregular and unpredictable in timing.

However, this very unevenness and irregularity offers

advantages to the value-oriented purchaser of fractional portions

of businesses. This investor may select from almost the entire

array of major American corporations, including many far superior

to virtually any of the businesses that could be bought in their

entirety in a negotiated deal. And fractional-interest purchases

can be made in an auction market where prices are set by

participants with behavior patterns that sometimes resemble those

of an army of manic-depressive lemmings.

Within this gigantic auction arena, it is our job to select

businesses with economic characteristics allowing each dollar of

retained earnings to be translated eventually into at least a

dollar of market value. Despite a lot of mistakes, we have so

far achieved this goal. In doing so, we have been greatly

assisted by Arthur Okun’s patron saint for economists - St.

Offset. In some cases, that is, retained earnings attributable

to our ownership position have had insignificant or even negative

impact on market value, while in other major positions a dollar

retained by an investee corporation has been translated into two

or more dollars of market value. To date, our corporate over-

achievers have more than offset the laggards. If we can continue

this record, it will validate our efforts to maximize “economic”

earnings, regardless of the impact upon “accounting” earnings.

Satisfactory as our partial-ownership approach has been,

what really makes us dance is the purchase of 100% of good

businesses at reasonable prices. We’ve accomplished this feat a

few times (and expect to do so again), but it is an

extraordinarily difficult job - far more difficult than the

purchase at attractive prices of fractional interests.

As we look at the major acquisitions that others made during

1982, our reaction is not envy, but relief that we were non-

participants. For in many of these acquisitions, managerial

intellect wilted in competition with managerial adrenaline The

thrill of the chase blinded the pursuers to the consequences of

the catch. Pascal’s observation seems apt: “It has struck me

that all men’s misfortunes spring from the single cause that they

are unable to stay quietly in one room.”

(Your Chairman left the room once too often last year and

almost starred in the Acquisition Follies of 1982. In

retrospect, our major accomplishment of the year was that a very

large purchase to which we had firmly committed was unable to be

completed for reasons totally beyond our control. Had it come

off, this transaction would have consumed extraordinary amounts

of time and energy, all for a most uncertain payoff. If we were

to introduce graphics to this report, illustrating favorable

business developments of the past year, two blank pages depicting

this blown deal would be the appropriate centerfold.)

Our partial-ownership approach can be continued soundly only

as long as portions of attractive businesses can be acquired at

attractive prices. We need a moderately-priced stock market to

assist us in this endeavor. The market, like the Lord, helps

those who help themselves. But, unlike the Lord, the market does

not forgive those who know not what they do. For the investor, a

too-high purchase price for the stock of an excellent company can

undo the effects of a subsequent decade of favorable business

developments.

Should the stock market advance to considerably higher

levels, our ability to utilize capital effectively in partial-

ownership positions will be reduced or eliminated. This will

happen periodically: just ten years ago, at the height of the

two-tier market mania (with high-return-on-equity businesses bid

to the sky by institutional investors), Berkshire’s insurance

subsidiaries owned only $18 million in market value of equities,

excluding their interest in Blue Chip Stamps. At that time, such

equity holdings amounted to about 15% of our insurance company

investments versus the present 80%. There were as many good

businesses around in 1972 as in 1982, but the prices the stock

�

market placed upon those businesses in 1972 looked absurd. While

high stock prices in the future would make our performance look

good temporarily, they would hurt our long-term business

prospects rather than help them. We currently are seeing early

traces of this problem.

Long-Term Corporate Performance

Our gain in net worth during 1982, valuing equities held by

our insurance subsidiaries at market value (less capital gain

taxes payable if unrealized gains were actually realized)

amounted to $208 million. On a beginning net worth base of $519

million, the percentage gain was 40%.

During the 18-year tenure of present management, book value

has grown from $19.46 per share to $737.43 per share, or 22.0%

compounded annually. You can be certain that this percentage

will diminish in the future. Geometric progressions eventually

forge their own anchors.

Berkshire’s economic goal remains to produce a long-term

rate of return well above the return achieved by the average

large American corporation. Our willingness to purchase either

partial or total ownership positions in favorably-situated

businesses, coupled with reasonable discipline about the prices

we are willing to pay, should give us a good chance of achieving

our goal.

Again this year the gain in market valuation of partially-

owned businesses outpaced the gain in underlying economic value

of those businesses. For example, $79 million of our $208

million gain is attributable to an increased market price for

GEICO. This company continues to do exceptionally well, and we

are more impressed than ever by the strength of GEICO’s basic

business idea and by the management skills of Jack Byrne.

(Although not found in the catechism of the better business

schools, “Let Jack Do It” works fine as a corporate creed for

us.)

However, GEICO’s increase in market value during the past

two years has been considerably greater than the gain in its

intrinsic business value, impressive as the latter has been. We

expected such a favorable variation at some point, as the

perception of investors converged with business reality. And we

look forward to substantial future gains in underlying business

value accompanied by irregular, but eventually full, market

recognition of such gains.

Year-to-year variances, however, cannot consistently be in

our favor. Even if our partially-owned businesses continue to

perform well in an economic sense, there will be years when they

perform poorly in the market. At such times our net worth could

shrink significantly. We will not be distressed by such a

shrinkage; if the businesses continue to look attractive and we

have cash available, we simply will add to our holdings at even

more favorable prices.

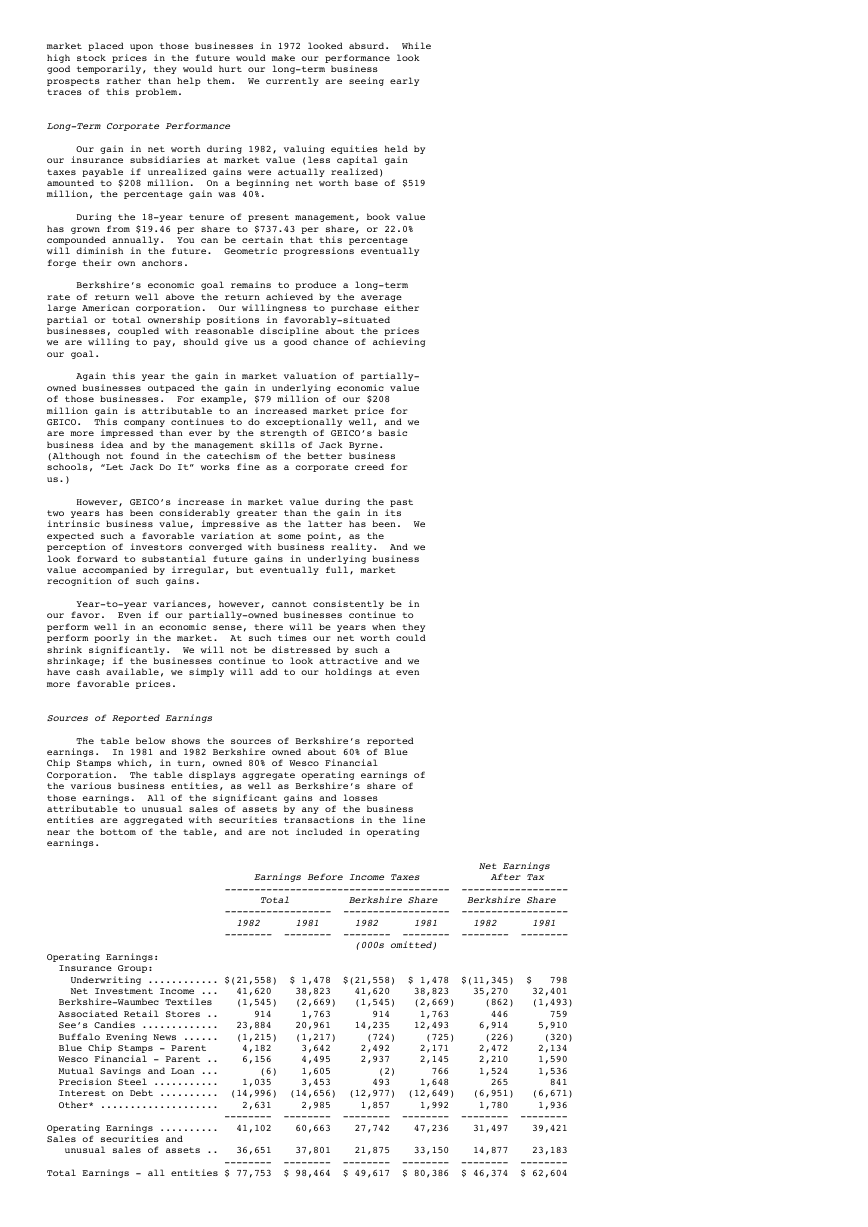

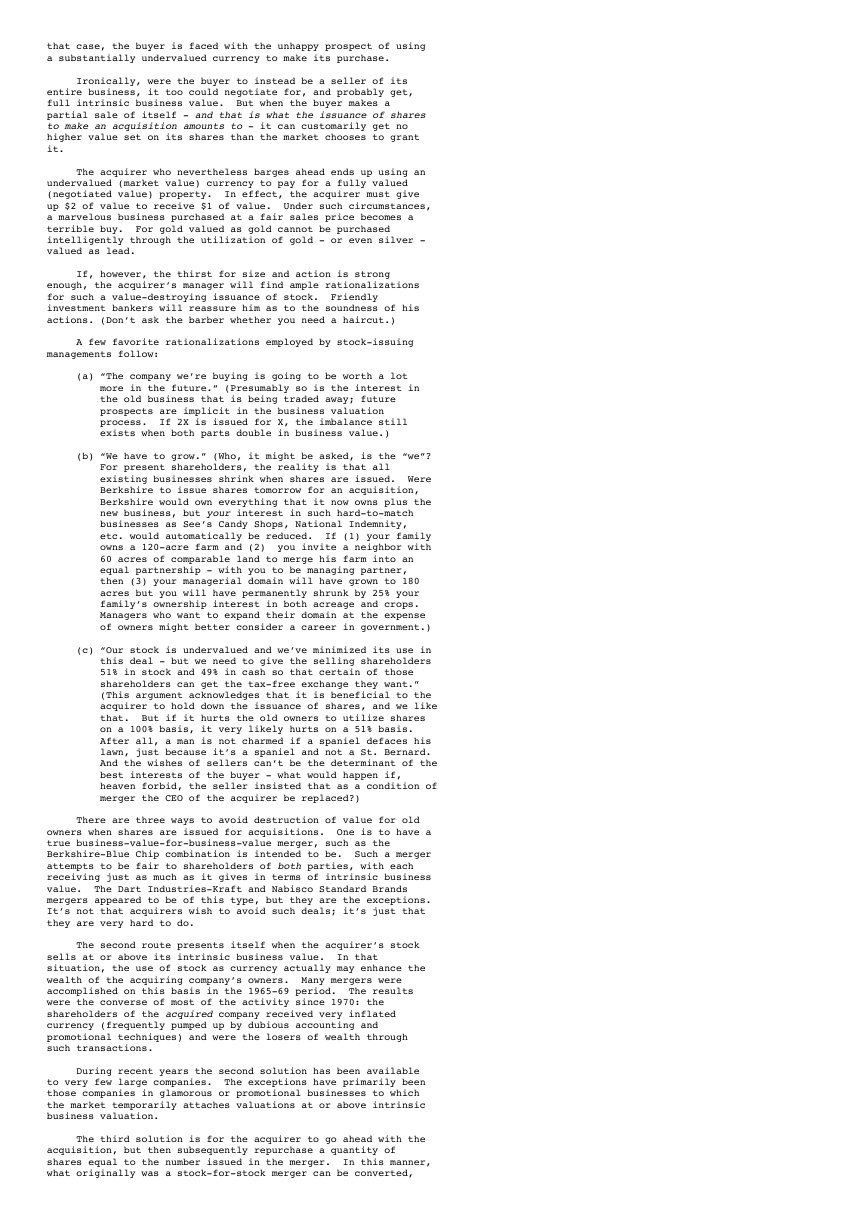

Sources of Reported Earnings

The table below shows the sources of Berkshire’s reported

earnings. In 1981 and 1982 Berkshire owned about 60% of Blue

Chip Stamps which, in turn, owned 80% of Wesco Financial

Corporation. The table displays aggregate operating earnings of

the various business entities, as well as Berkshire’s share of

those earnings. All of the significant gains and losses

attributable to unusual sales of assets by any of the business

entities are aggregated with securities transactions in the line

near the bottom of the table, and are not included in operating

earnings.

Net Earnings

Earnings Before Income Taxes After Tax

-------------------------------------- ------------------

Total Berkshire Share Berkshire Share

------------------ ------------------ ------------------

1982 1981 1982 1981 1982 1981

-------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --------

(000s omitted)

Operating Earnings:

Insurance Group:

Underwriting ............ $(21,558) $ 1,478 $(21,558) $ 1,478 $(11,345) $ 798

Net Investment Income ... 41,620 38,823 41,620 38,823 35,270 32,401

Berkshire-Waumbec Textiles (1,545) (2,669) (1,545) (2,669) (862) (1,493)

Associated Retail Stores .. 914 1,763 914 1,763 446 759

See’s Candies ............. 23,884 20,961 14,235 12,493 6,914 5,910

Buffalo Evening News ...... (1,215) (1,217) (724) (725) (226) (320)

Blue Chip Stamps - Parent 4,182 3,642 2,492 2,171 2,472 2,134

Wesco Financial - Parent .. 6,156 4,495 2,937 2,145 2,210 1,590

Mutual Savings and Loan ... (6) 1,605 (2) 766 1,524 1,536

Precision Steel ........... 1,035 3,453 493 1,648 265 841

Interest on Debt .......... (14,996) (14,656) (12,977) (12,649) (6,951) (6,671)

Other* .................... 2,631 2,985 1,857 1,992 1,780 1,936

-------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --------

Operating Earnings .......... 41,102 60,663 27,742 47,236 31,497 39,421

Sales of securities and

unusual sales of assets .. 36,651 37,801 21,875 33,150 14,877 23,183

-------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --------

Total Earnings - all entities $ 77,753 $ 98,464 $ 49,617 $ 80,386 $ 46,374 $ 62,604

�

======== ======== ======== ======== ======== ========

* Amortization of intangibles arising in accounting for purchases

of businesses (i.e. See’s, Mutual and Buffalo Evening News) is

reflected in the category designated as “Other”.

On pages 45-61 of this report we have reproduced the

narrative reports of the principal executives of Blue Chip and

Wesco, in which they describe 1982 operations. A copy of the

full annual report of either company will be mailed to any

Berkshire shareholder upon request to Mr. Robert H. Bird for

Blue Chip Stamps, 5801 South Eastern Avenue, Los Angeles,

California 90040, or to Mrs. Jeanne Leach for Wesco Financial

Corporation, 315 East Colorado Boulevard, Pasadena, California

91109.

I believe you will find the Blue Chip chronicle of

developments in the Buffalo newspaper situation particularly

interesting. There are now only 14 cities in the United States

with a daily newspaper whose weekday circulation exceeds that of

the Buffalo News. But the real story has been the growth in

Sunday circulation. Six years ago, prior to introduction of a

Sunday edition of the News, the long-established Courier-Express,

as the only Sunday newspaper published in Buffalo, had

circulation of 272,000. The News now has Sunday circulation of

367,000, a 35% gain - even though the number of households within

the primary circulation area has shown little change during the

six years. We know of no city in the United States with a long

history of seven-day newspaper publication in which the

percentage of households purchasing the Sunday newspaper has

grown at anything like this rate. To the contrary, in most

cities household penetration figures have grown negligibly, or

not at all. Our key managers in Buffalo - Henry Urban, Stan

Lipsey, Murray Light, Clyde Pinson, Dave Perona and Dick Feather

- deserve great credit for this unmatched expansion in Sunday

readership.

As we indicated earlier, undistributed earnings in companies

we do not control are now fully as important as the reported

operating earnings detailed in the preceding table. The

distributed portion of non-controlled earnings, of course, finds

its way into that table primarily through the net investment

income segment of Insurance Group earnings.

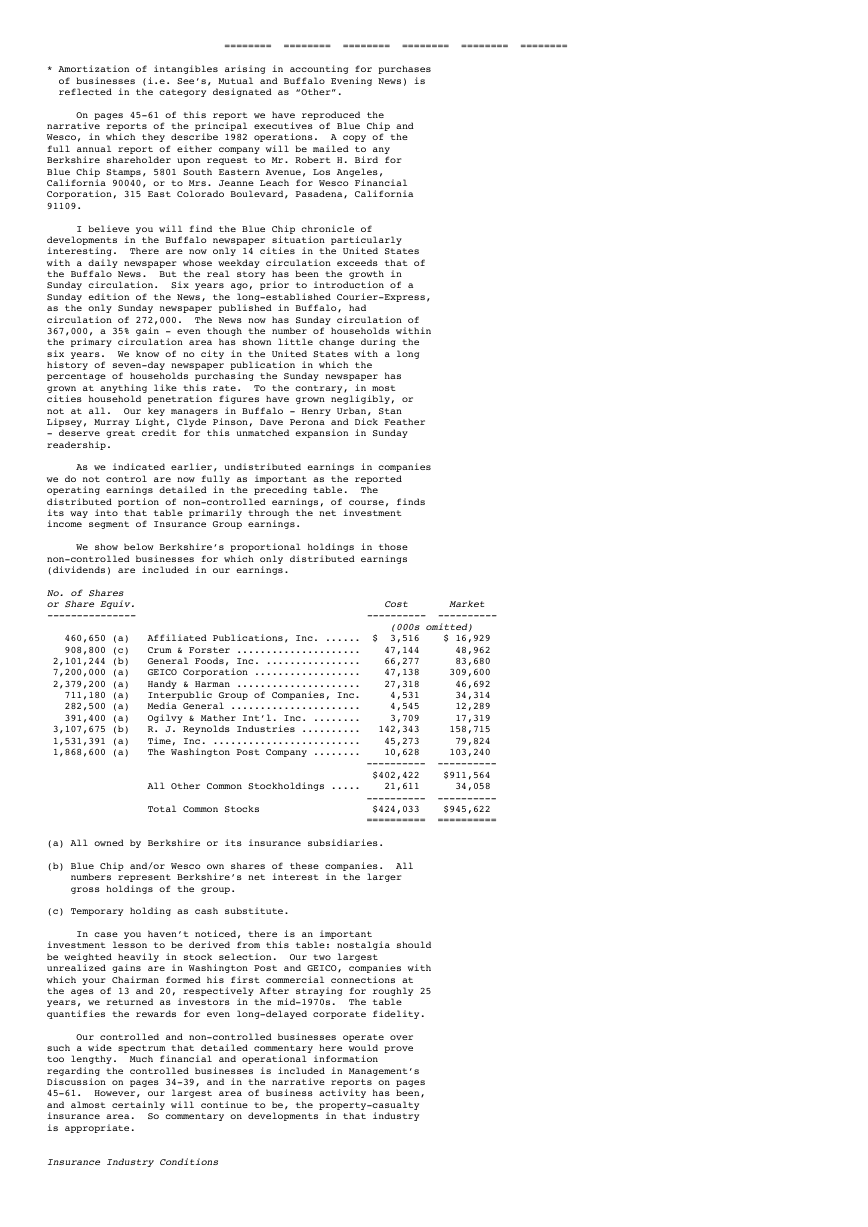

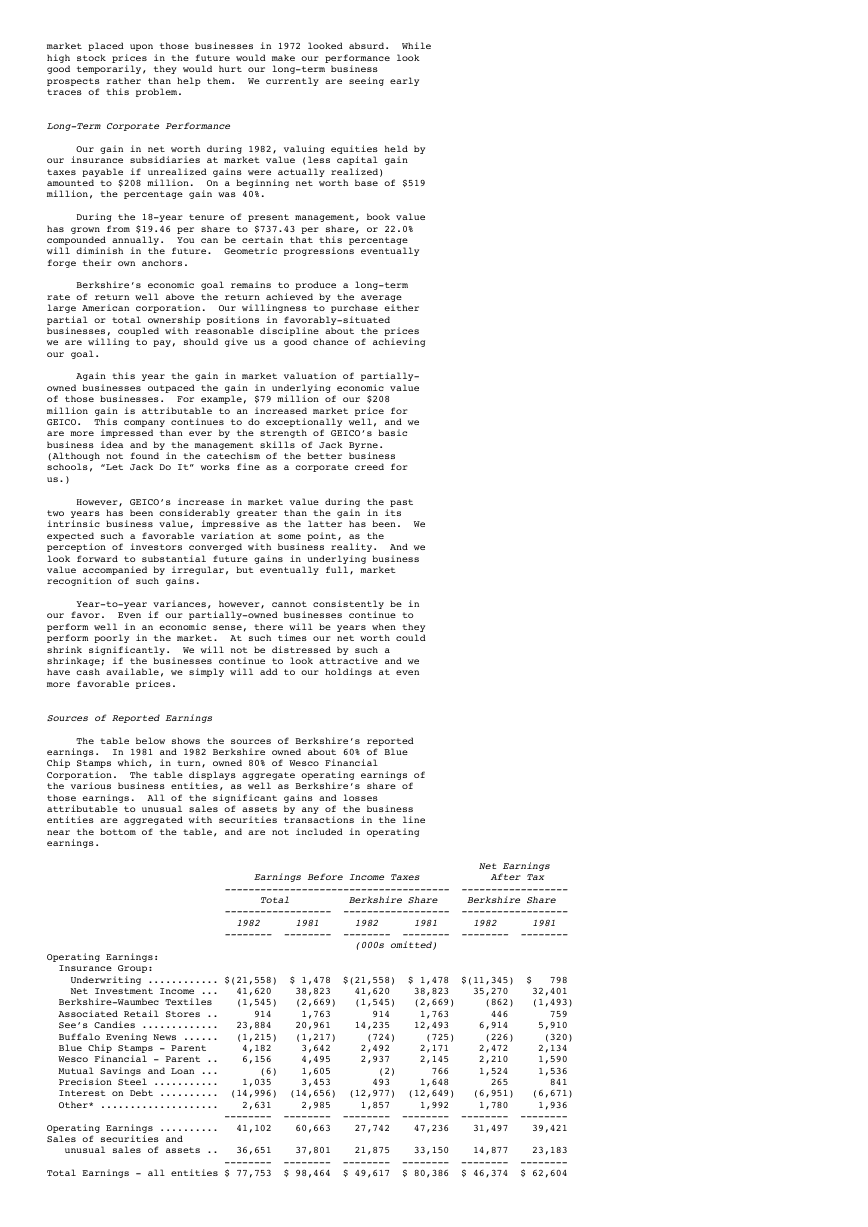

We show below Berkshire’s proportional holdings in those

non-controlled businesses for which only distributed earnings

(dividends) are included in our earnings.

No. of Shares

or Share Equiv. Cost Market

--------------- ---------- ----------

(000s omitted)

460,650 (a) Affiliated Publications, Inc. ...... $ 3,516 $ 16,929

908,800 (c) Crum & Forster ..................... 47,144 48,962

2,101,244 (b) General Foods, Inc. ................ 66,277 83,680

7,200,000 (a) GEICO Corporation .................. 47,138 309,600

2,379,200 (a) Handy & Harman ..................... 27,318 46,692

711,180 (a) Interpublic Group of Companies, Inc. 4,531 34,314

282,500 (a) Media General ...................... 4,545 12,289

391,400 (a) Ogilvy & Mather Int’l. Inc. ........ 3,709 17,319

3,107,675 (b) R. J. Reynolds Industries .......... 142,343 158,715

1,531,391 (a) Time, Inc. ......................... 45,273 79,824

1,868,600 (a) The Washington Post Company ........ 10,628 103,240

---------- ----------

$402,422 $911,564

All Other Common Stockholdings ..... 21,611 34,058

---------- ----------

Total Common Stocks $424,033 $945,622

========== ==========

(a) All owned by Berkshire or its insurance subsidiaries.

(b) Blue Chip and/or Wesco own shares of these companies. All

numbers represent Berkshire’s net interest in the larger

gross holdings of the group.

(c) Temporary holding as cash substitute.

In case you haven’t noticed, there is an important

investment lesson to be derived from this table: nostalgia should

be weighted heavily in stock selection. Our two largest

unrealized gains are in Washington Post and GEICO, companies with

which your Chairman formed his first commercial connections at

the ages of 13 and 20, respectively After straying for roughly 25

years, we returned as investors in the mid-1970s. The table

quantifies the rewards for even long-delayed corporate fidelity.

Our controlled and non-controlled businesses operate over

such a wide spectrum that detailed commentary here would prove

too lengthy. Much financial and operational information

regarding the controlled businesses is included in Management’s

Discussion on pages 34-39, and in the narrative reports on pages

45-61. However, our largest area of business activity has been,

and almost certainly will continue to be, the property-casualty

insurance area. So commentary on developments in that industry

is appropriate.

Insurance Industry Conditions

�

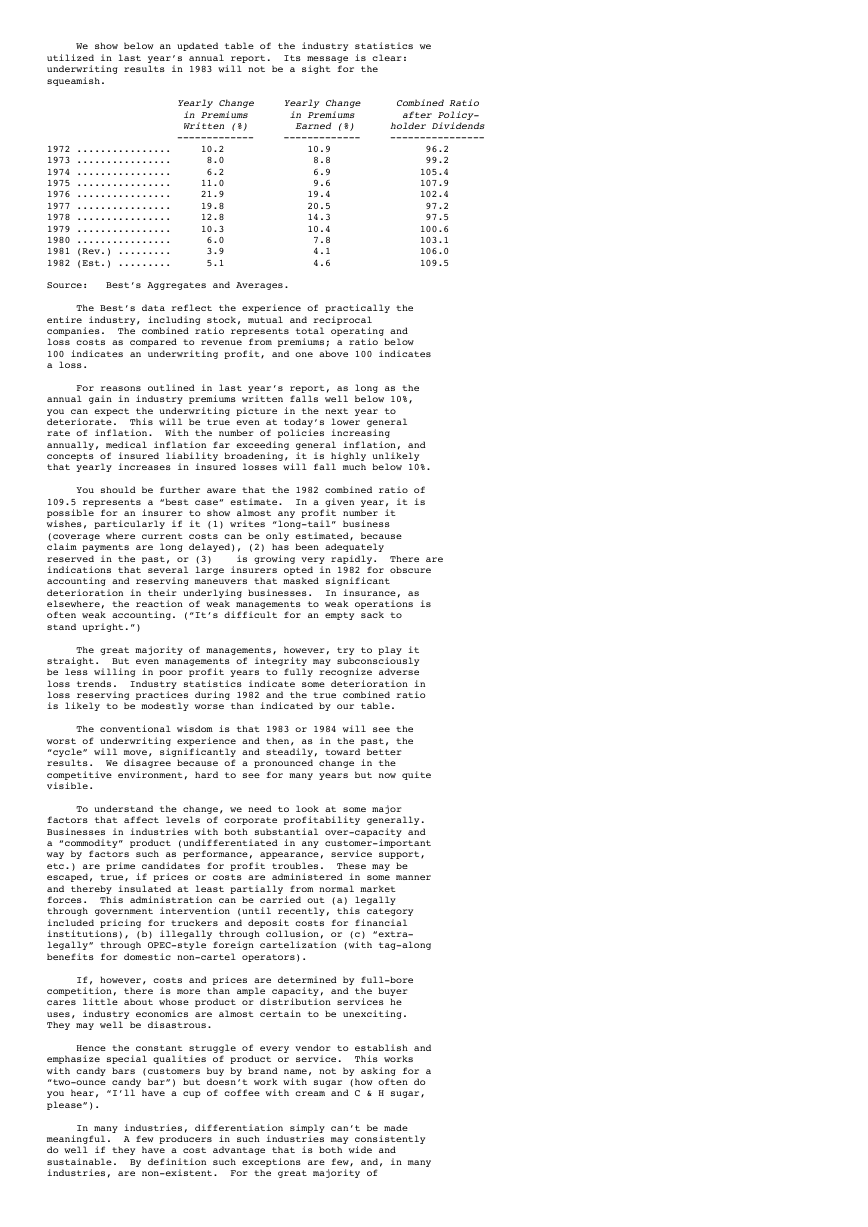

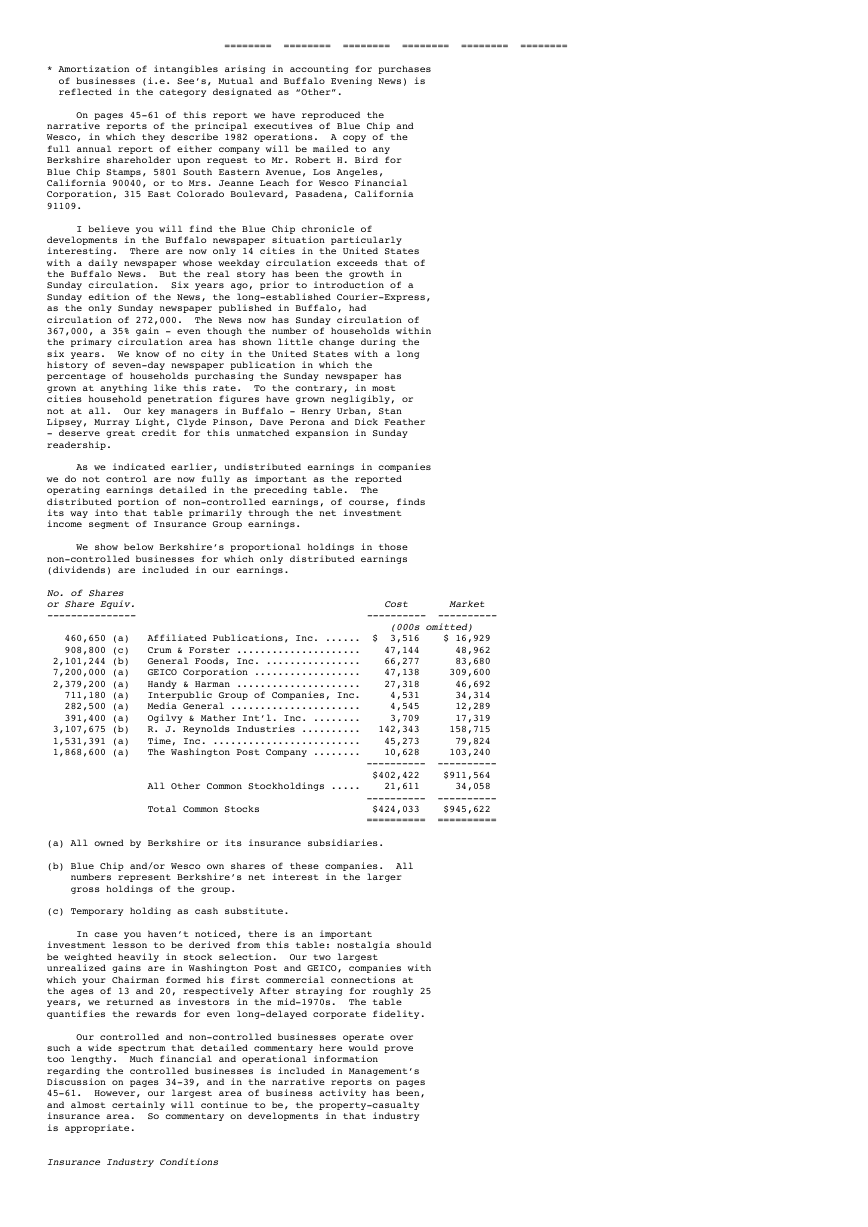

We show below an updated table of the industry statistics we

utilized in last year’s annual report. Its message is clear:

underwriting results in 1983 will not be a sight for the

squeamish.

Yearly Change Yearly Change Combined Ratio

in Premiums in Premiums after Policy-

Written (%) Earned (%) holder Dividends

------------- ------------- ----------------

1972 ................ 10.2 10.9 96.2

1973 ................ 8.0 8.8 99.2

1974 ................ 6.2 6.9 105.4

1975 ................ 11.0 9.6 107.9

1976 ................ 21.9 19.4 102.4

1977 ................ 19.8 20.5 97.2

1978 ................ 12.8 14.3 97.5

1979 ................ 10.3 10.4 100.6

1980 ................ 6.0 7.8 103.1

1981 (Rev.) ......... 3.9 4.1 106.0

1982 (Est.) ......... 5.1 4.6 109.5

Source: Best’s Aggregates and Averages.

The Best’s data reflect the experience of practically the

entire industry, including stock, mutual and reciprocal

companies. The combined ratio represents total operating and

loss costs as compared to revenue from premiums; a ratio below

100 indicates an underwriting profit, and one above 100 indicates

a loss.

For reasons outlined in last year’s report, as long as the

annual gain in industry premiums written falls well below 10%,

you can expect the underwriting picture in the next year to

deteriorate. This will be true even at today’s lower general

rate of inflation. With the number of policies increasing

annually, medical inflation far exceeding general inflation, and

concepts of insured liability broadening, it is highly unlikely

that yearly increases in insured losses will fall much below 10%.

You should be further aware that the 1982 combined ratio of

109.5 represents a “best case” estimate. In a given year, it is

possible for an insurer to show almost any profit number it

wishes, particularly if it (1) writes “long-tail” business

(coverage where current costs can be only estimated, because

claim payments are long delayed), (2) has been adequately

reserved in the past, or (3)

indications that several large insurers opted in 1982 for obscure

accounting and reserving maneuvers that masked significant

deterioration in their underlying businesses. In insurance, as

elsewhere, the reaction of weak managements to weak operations is

often weak accounting. (“It’s difficult for an empty sack to

stand upright.”)

is growing very rapidly. There are

The great majority of managements, however, try to play it

straight. But even managements of integrity may subconsciously

be less willing in poor profit years to fully recognize adverse

loss trends. Industry statistics indicate some deterioration in

loss reserving practices during 1982 and the true combined ratio

is likely to be modestly worse than indicated by our table.

The conventional wisdom is that 1983 or 1984 will see the

worst of underwriting experience and then, as in the past, the

“cycle” will move, significantly and steadily, toward better

results. We disagree because of a pronounced change in the

competitive environment, hard to see for many years but now quite

visible.

To understand the change, we need to look at some major

factors that affect levels of corporate profitability generally.

Businesses in industries with both substantial over-capacity and

a “commodity” product (undifferentiated in any customer-important

way by factors such as performance, appearance, service support,

etc.) are prime candidates for profit troubles. These may be

escaped, true, if prices or costs are administered in some manner

and thereby insulated at least partially from normal market

forces. This administration can be carried out (a) legally

through government intervention (until recently, this category

included pricing for truckers and deposit costs for financial

institutions), (b) illegally through collusion, or (c) “extra-

legally” through OPEC-style foreign cartelization (with tag-along

benefits for domestic non-cartel operators).

If, however, costs and prices are determined by full-bore

competition, there is more than ample capacity, and the buyer

cares little about whose product or distribution services he

uses, industry economics are almost certain to be unexciting.

They may well be disastrous.

Hence the constant struggle of every vendor to establish and

emphasize special qualities of product or service. This works

with candy bars (customers buy by brand name, not by asking for a

“two-ounce candy bar”) but doesn’t work with sugar (how often do

you hear, “I’ll have a cup of coffee with cream and C & H sugar,

please”).

In many industries, differentiation simply can’t be made

meaningful. A few producers in such industries may consistently

do well if they have a cost advantage that is both wide and

sustainable. By definition such exceptions are few, and, in many

industries, are non-existent. For the great majority of

�

companies selling “commodity”products, a depressing equation of

business economics prevails: persistent over-capacity without

administered prices (or costs) equals poor profitability.

Of course, over-capacity may eventually self-correct, either

as capacity shrinks or demand expands. Unfortunately for the

participants, such corrections often are long delayed. When they

finally occur, the rebound to prosperity frequently produces a

pervasive enthusiasm for expansion that, within a few years,

again creates over-capacity and a new profitless environment. In

other words, nothing fails like success.

What finally determines levels of long-term profitability in

such industries is the ratio of supply-tight to supply-ample

years. Frequently that ratio is dismal. (It seems as if the most

recent supply-tight period in our textile business - it occurred

some years back - lasted the better part of a morning.)

In some industries, however, capacity-tight conditions can

last a long time. Sometimes actual growth in demand will outrun

forecasted growth for an extended period. In other cases, adding

capacity requires very long lead times because complicated

manufacturing facilities must be planned and built.

But in the insurance business, to return to that subject,

capacity can be instantly created by capital plus an

underwriter’s willingness to sign his name. (Even capital is less

important in a world in which state-sponsored guaranty funds

protect many policyholders against insurer insolvency.) Under

almost all conditions except that of fear for survival -

produced, perhaps, by a stock market debacle or a truly major

natural disaster - the insurance industry operates under the

competitive sword of substantial overcapacity. Generally, also,

despite heroic attempts to do otherwise, the industry sells a

relatively undifferentiated commodity-type product. (Many

insureds, including the managers of large businesses, do not even

know the names of their insurers.) Insurance, therefore, would

seem to be a textbook case of an industry usually faced with the

deadly combination of excess capacity and a “commodity” product.

Why, then, was underwriting, despite the existence of

cycles, generally profitable over many decades? (From 1950

through 1970, the industry combined ratio averaged 99.0.

allowing all investment income plus 1% of premiums to flow

through to profits.) The answer lies primarily in the historic

methods of regulation and distribution. For much of this

century, a large portion of the industry worked, in effect,

within a legal quasi-administered pricing system fostered by

insurance regulators. While price competition existed, it was

not pervasive among the larger companies. The main competition

was for agents, who were courted via various non-price-related

strategies.

For the giants of the industry, most rates were set through

negotiations between industry “bureaus” (or through companies

acting in accord with their recommendations) and state

regulators. Dignified haggling occurred, but it was between

company and regulator rather than between company and customer.

When the dust settled, Giant A charged the same price as Giant B

- and both companies and agents were prohibited by law from

cutting such filed rates.

The company-state negotiated prices included specific profit

allowances and, when loss data indicated that current prices were

unprofitable, both company managements and state regulators

expected that they would act together to correct the situation.

Thus, most of the pricing actions of the giants of the industry

were “gentlemanly”, predictable, and profit-producing. Of prime

importance - and in contrast to the way most of the business

world operated - insurance companies could legally price their

way to profitability even in the face of substantial over-

capacity.

That day is gone. Although parts of the old structure

remain, far more than enough new capacity exists outside of that

structure to force all parties, old and new, to respond. The new

capacity uses various methods of distribution and is not

reluctant to use price as a prime competitive weapon. Indeed, it

relishes that use. In the process, customers have learned that

insurance is no longer a one-price business. They won’t forget.

Future profitability of the industry will be determined by

current competitive characteristics, not past ones. Many

managers have been slow to recognize this. It’s not only

generals that prefer to fight the last war. Most business and

investment analysis also comes from the rear-view mirror. It

seems clear to us, however, that only one condition will allow

the insurance industry to achieve significantly improved

underwriting results. That is the same condition that will allow

better results for the aluminum, copper, or corn producer - a

major narrowing of the gap between demand and supply.

Unfortunately, there can be no surge in demand for insurance

policies comparable to one that might produce a market tightness

in copper or aluminum. Rather, the supply of available insurance

coverage must be curtailed. “Supply”, in this context, is mental

rather than physical: plants or companies need not be shut; only

the willingness of underwriters to sign their names need be

curtailed.

�

This contraction will not happen because of generally poor

profit levels. Bad profits produce much hand-wringing and

finger-pointing. But they do not lead major sources of insurance

capacity to turn their backs on very large chunks of business,

thereby sacrificing market share and industry significance.

Instead, major capacity withdrawals require a shock factor

such as a natural or financial “megadisaster”. One might occur

tomorrow - or many years from now. The insurance business - even

taking investment income into account - will not be particularly

profitable in the meantime.

When supply ultimately contracts, large amounts of business

will be available for the few with large capital capacity, a

willingness to commit it, and an in-place distribution system.

We would expect great opportunities for our insurance

subsidiaries at such a time.

During 1982, our insurance underwriting deteriorated far

more than did the industry’s. From a profit position well above

average, we, slipped to a performance modestly below average.

The biggest swing was in National Indemnity’s traditional

coverages. Lines that have been highly profitable for us in the

past are now priced at levels that guarantee underwriting losses.

In 1983 we expect our insurance group to record an average

performance in an industry in which average is very poor.

Two of our stars, Milt Thornton at Cypress and Floyd Taylor

at Kansas Fire and Casualty, continued their outstanding records

of producing an underwriting profit every year since joining us.

Both Milt and Floyd simply are incapable of being average. They

maintain a passionately proprietary attitude toward their

operations and have developed a business culture centered upon

unusual cost-consciousness and customer service. It shows on

their scorecards.

During 1982, parent company responsibility for most of our

insurance operations was given to Mike Goldberg. Planning,

recruitment, and monitoring all have shown significant

improvement since Mike replaced me in this role.

GEICO continues to be managed with a zeal for efficiency and

value to the customer that virtually guarantees unusual success.

Jack Byrne and Bill Snyder are achieving the most elusive of

human goals - keeping things simple and remembering what you set

out to do. In Lou Simpson, additionally, GEICO has the best

investment manager in the property-casualty business. We are

happy with every aspect of this operation. GEICO is a

magnificent illustration of the high-profit exception we

described earlier in discussing commodity industries with over-

capacity - a company with a wide and sustainable cost advantage.

Our 35% interest in GEICO represents about $250 million of

premium volume, an amount considerably greater than all of the

direct volume we produce.

Issuance of Equity

Berkshire and Blue Chip are considering merger in 1983. If

it takes place, it will involve an exchange of stock based upon

an identical valuation method applied to both companies. The one

other significant issuance of shares by Berkshire or its

affiliated companies that occurred during present management’s

tenure was in the 1978 merger of Berkshire with Diversified

Retailing Company.

Our share issuances follow a simple basic rule: we will not

issue shares unless we receive as much intrinsic business value

as we give. Such a policy might seem axiomatic. Why, you might

ask, would anyone issue dollar bills in exchange for fifty-cent

pieces? Unfortunately, many corporate managers have been willing

to do just that.

The first choice of these managers in making acquisitions

may be to use cash or debt. But frequently the CEO’s cravings

outpace cash and credit resources (certainly mine always have).

Frequently, also, these cravings occur when his own stock is

selling far below intrinsic business value. This state of

affairs produces a moment of truth. At that point, as Yogi Berra

has said, “You can observe a lot just by watching.” For

shareholders then will find which objective the management truly

prefers - expansion of domain or maintenance of owners’ wealth.

The need to choose between these objectives occurs for some

simple reasons. Companies often sell in the stock market below

their intrinsic business value. But when a company wishes to

sell out completely, in a negotiated transaction, it inevitably

wants to - and usually can - receive full business value in

whatever kind of currency the value is to be delivered. If cash

is to be used in payment, the seller’s calculation of value

received couldn’t be easier. If stock of the buyer is to be the

currency, the seller’s calculation is still relatively easy: just

figure the market value in cash of what is to be received in

stock.

Meanwhile, the buyer wishing to use his own stock as

currency for the purchase has no problems if the stock is selling

in the market at full intrinsic value.

But suppose it is selling at only half intrinsic value. In

�

that case, the buyer is faced with the unhappy prospect of using

a substantially undervalued currency to make its purchase.

Ironically, were the buyer to instead be a seller of its

entire business, it too could negotiate for, and probably get,

full intrinsic business value. But when the buyer makes a

partial sale of itself - and that is what the issuance of shares

to make an acquisition amounts to - it can customarily get no

higher value set on its shares than the market chooses to grant

it.

The acquirer who nevertheless barges ahead ends up using an

undervalued (market value) currency to pay for a fully valued

(negotiated value) property. In effect, the acquirer must give

up $2 of value to receive $1 of value. Under such circumstances,

a marvelous business purchased at a fair sales price becomes a

terrible buy. For gold valued as gold cannot be purchased

intelligently through the utilization of gold - or even silver -

valued as lead.

If, however, the thirst for size and action is strong

enough, the acquirer’s manager will find ample rationalizations

for such a value-destroying issuance of stock. Friendly

investment bankers will reassure him as to the soundness of his

actions. (Don’t ask the barber whether you need a haircut.)

A few favorite rationalizations employed by stock-issuing

managements follow:

(a) “The company we’re buying is going to be worth a lot

more in the future.” (Presumably so is the interest in

the old business that is being traded away; future

prospects are implicit in the business valuation

process. If 2X is issued for X, the imbalance still

exists when both parts double in business value.)

(b) “We have to grow.” (Who, it might be asked, is the “we”?

For present shareholders, the reality is that all

existing businesses shrink when shares are issued. Were

Berkshire to issue shares tomorrow for an acquisition,

Berkshire would own everything that it now owns plus the

new business, but your interest in such hard-to-match

businesses as See’s Candy Shops, National Indemnity,

etc. would automatically be reduced. If (1) your family

owns a 120-acre farm and (2) you invite a neighbor with

60 acres of comparable land to merge his farm into an

equal partnership - with you to be managing partner,

then (3) your managerial domain will have grown to 180

acres but you will have permanently shrunk by 25% your

family’s ownership interest in both acreage and crops.

Managers who want to expand their domain at the expense

of owners might better consider a career in government.)

(c) “Our stock is undervalued and we’ve minimized its use in

this deal - but we need to give the selling shareholders

51% in stock and 49% in cash so that certain of those

shareholders can get the tax-free exchange they want.”

(This argument acknowledges that it is beneficial to the

acquirer to hold down the issuance of shares, and we like

that. But if it hurts the old owners to utilize shares

on a 100% basis, it very likely hurts on a 51% basis.

After all, a man is not charmed if a spaniel defaces his

lawn, just because it’s a spaniel and not a St. Bernard.

And the wishes of sellers can’t be the determinant of the

best interests of the buyer - what would happen if,

heaven forbid, the seller insisted that as a condition of

merger the CEO of the acquirer be replaced?)

There are three ways to avoid destruction of value for old

owners when shares are issued for acquisitions. One is to have a

true business-value-for-business-value merger, such as the

Berkshire-Blue Chip combination is intended to be. Such a merger

attempts to be fair to shareholders of both parties, with each

receiving just as much as it gives in terms of intrinsic business

value. The Dart Industries-Kraft and Nabisco Standard Brands

mergers appeared to be of this type, but they are the exceptions.

It’s not that acquirers wish to avoid such deals; it’s just that

they are very hard to do.

The second route presents itself when the acquirer’s stock

sells at or above its intrinsic business value. In that

situation, the use of stock as currency actually may enhance the

wealth of the acquiring company’s owners. Many mergers were

accomplished on this basis in the 1965-69 period. The results

were the converse of most of the activity since 1970: the

shareholders of the acquired company received very inflated

currency (frequently pumped up by dubious accounting and

promotional techniques) and were the losers of wealth through

such transactions.

During recent years the second solution has been available

to very few large companies. The exceptions have primarily been

those companies in glamorous or promotional businesses to which

the market temporarily attaches valuations at or above intrinsic

business valuation.

The third solution is for the acquirer to go ahead with the

acquisition, but then subsequently repurchase a quantity of

shares equal to the number issued in the merger. In this manner,

what originally was a stock-for-stock merger can be converted,

�