The Academic Phrasebank is a

general resource for academic

writers. It makes explicit the more

common phraseological ‘nuts and

bolts’ of academic writing.

Academic

Phrasebank

A compendium of commonly

used phrasal elements in

academic English in PDF format

2018 enhanced edition

Dr John Morley

�

Navigable PDF version

©2018 The University of Manchester

The Academic Phrasebank is for the sole use of the individual who has downloaded it from www.click2go.umip.com.

Distribution of The Academic Phrasebank by electronic (e.g. via email, web download) or any other means is strictly

prohibited and constitutes copyright infringement.

The Academic Phrasebank is only available on this website: http://www.click2go.umip.com/ct/academic_phrasebank/ or on

the Kindle store (search “Academic Phrasebank” in your regional Kindle store). If you see this version of The Academic

Phrasebank made available anywhere else, please contact express@umip.com immediately.

�

Preface

The Academic Phrasebank is a general resource for academic writers. It aims to provide the

phraseological ‘nuts and bolts’ of academic writing organised according to the main sections of a

research paper or dissertation. Other phrases are listed under the more general communicative

functions of academic writing.

The resource was designed primarily for academic and scientific writers who are non-native speakers

of English. However, native writers may still find much of the material helpful. In fact, recent data

suggest that the majority of users are native speakers of English.

The phrases, and the headings under which they are listed, can be used simply to assist you in

thinking about the content and organisation of your own writing, or the phrases can be incorporated

into your writing where this is appropriate. In most cases, a certain amount of creativity and

adaptation will be necessary when a phrase is used.

The Academic Phrasebank is not discipline specific. Nevertheless, it should be particularly useful for

writers who need to report their empirical studies. The phrases are content neutral and generic in

nature; in using them, therefore, you are not stealing other people's ideas and this does not

constitute plagiarism.

Most of the phrases in this compendium have been organised according to the main sections of a

research report. However, it is an over-simplification to associate the phrases only with the section in

which they have been placed here. In reality, for example, many of phrases used for referring to

other studies may be found throughout a research report.

In the current PDF version, additional material, which is not phraseological, has been incorporated.

These additional sections should be helpful to you as a writer.

Dr John Morley, 2018

2 | P a g e

�

……………………………………………..……..…..................

……………………………………………..………....................

……………………………………………..………….................

……………………………………………..………....................

……………………………………………..………....................

……………………………………………..………....................

……………………………………………..………....................

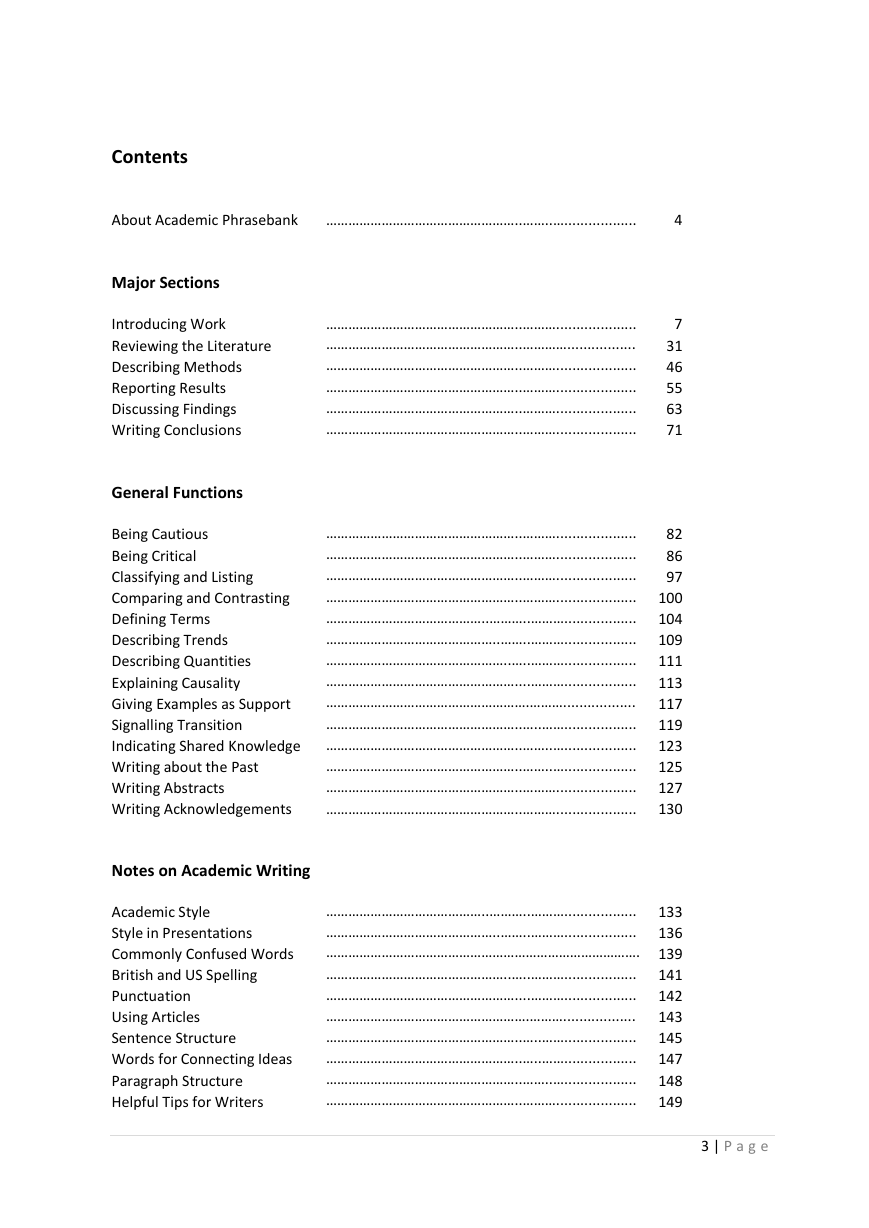

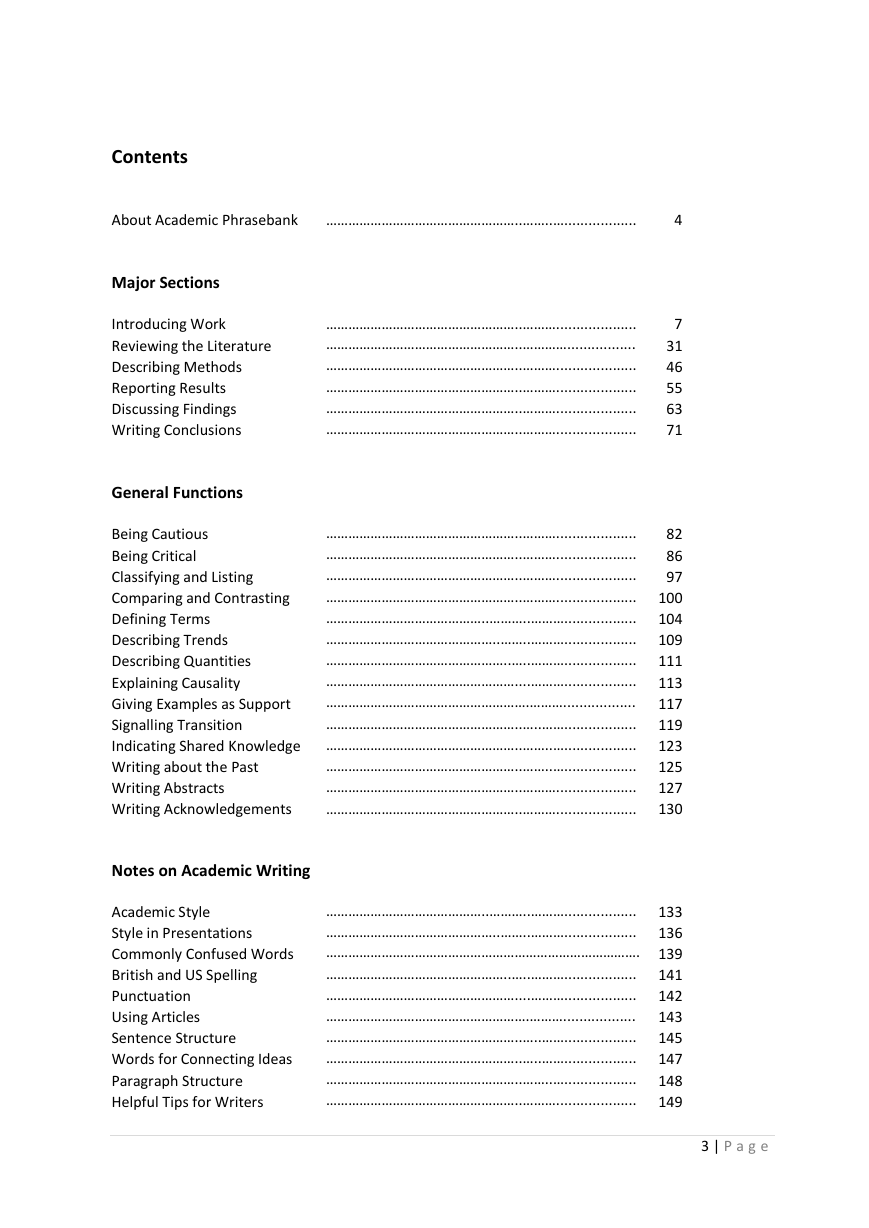

Contents

About Academic Phrasebank

Major Sections

Introducing Work

Reviewing the Literature

Describing Methods

Reporting Results

Discussing Findings

Writing Conclusions

General Functions

……………………………………………..………....................

Being Cautious

……………………………………………..………....................

Being Critical

……………………………………………..………....................

Classifying and Listing

……………………………………………..………....................

Comparing and Contrasting

……………………………………..………..………..................

Defining Terms

………………………………………..……..………..................

Describing Trends

…………………………………………..…..………..................

Describing Quantities

……………………………………………....………..................

Explaining Causality

……………………………………………….………..................

Giving Examples as Support

……………………………………………..…..……..................

Signalling Transition

Indicating Shared Knowledge ……………………………………………..……..…..................

……………………………………………..……..…..................

Writing about the Past

……………………………………………..………....................

Writing Abstracts

……………………………………………..………....................

Writing Acknowledgements

Notes on Academic Writing

Academic Style

Style in Presentations

Commonly Confused Words

British and US Spelling

Punctuation

Using Articles

Sentence Structure

Words for Connecting Ideas

Paragraph Structure

Helpful Tips for Writers

……………………………………..………..………..................

………………………………………..……..………..................

………………………………………………………………………….

…………………………………………..…..………..................

……………………………………………....………..................

……………………………………………….………..................

……………………………………………..…..……..................

……………………………………………..…..……..................

……………………………………………..……..…..................

……………………………………………..………....................

4

7

31

46

55

63

71

82

86

97

100

104

109

111

113

117

119

123

125

127

130

133

136

139

141

142

143

145

147

148

149

3 | P a g e

�

About Academic Phrasebank

Theoretical Influences

The Academic Phrasebank largely draws on an approach to analysing academic texts originally

pioneered by John Swales in the 1980s. Utilising a genre analysis approach to identify rhetorical

patterns in the introductions to research articles, Swales defined a ‘move’ as a section of text that

serves a specific communicative function (Swales, 1981,1990). This unit of rhetorical analysis is used

as one of the main organising sub-categories of the Academic Phrasebank. Swales not only identified

commonly-used moves in article introductions, but he was interested in showing the kind of

language which was used to achieve the communicative purpose of each move. Much of this

language was phraseological in nature.

The resource also draws upon psycholinguistic insights into how language is learnt and produced. It is

now accepted that much of the language we use is phraseological; that it is acquired, stored and

retrieved as pre-formulated constructions (Bolinger, 1976; Pawley and Syder, 1983). These insights

began to be supported empirically as computer technology permitted the identification of recurrent

phraseological patterns in very large corpora of spoken and written English using specialised

software (e.g. Sinclair, 1991). Phrasebank recognises that there is an important phraseological

dimension to academic language and attempts to make examples of this explicit.

Sources of the phrases

The vast majority of phrases in this resource have been taken from authentic academic sources. The

original corpus from which the phrases were ‘harvested’ consisted of 100 postgraduate dissertations

completed at the University of Manchester. However, phrases from academic articles drawn from a

broad spectrum of disciplines have also been, and continue to be, incorporated. In most cases, the

phrases have been simplified and where necessary they have been ‘sifted’ from their particularised

academic content. Where content words have been included for exemplificatory purposes, these are

substitutions of the original words. In selecting a phrase for inclusion into the Academic Phrasebank,

the following questions are asked:

• does it serve a useful communicative purpose in academic text?

• does it contain collocational and/or formulaic elements?

• are the content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives) generic in nature?

• does the combination ‘sound natural' to a native speaker or writer of English?

When is it acceptable to reuse phrases in academic writing?

In a recent study (Davis and Morley, 2015), 45 academics from two British universities were surveyed

to determine whether reusing phrases was a legitimate activity for academic writers, and if so, what

kind of phrases could be reused. From the survey and later from in-depth interviews, the following

characteristics for acceptability emerged. A reused phrase:

should not have a unique or original construction;

should not express a clear point of view of another writer;

•

•

• depending on the phrase, may be up to nine words in length; beyond this 'acceptability'

• may contain up to four generic content words (nouns, verbs or adjectives which are not

declines;

bound to a specific topic).

Some of the entries in the Academic Phrasebank, contain specific content words which have been

included for illustrative purposes. These words should be substituted when the phrases are used. In

the phrases below, for example, the content words in bold should be substituted:

4 | P a g e

�

• X is a major public health problem, and the cause of ...

• X is the leading cause of death in western-industrialised countries.

The many thousands of disciplinary-specific phrases which can be found in academic communication

comprise a separate category of phrases. These tend to be shorter than the generic phrases listed in

Academic Phrasebank, and typically consist of noun phrases or combinations of these. Acceptability

for reusing these is determined by the extent to which they are used and understood by members of

a particular academic community.

Further work

Development of the website content is ongoing. In addition, research is currently being carried out

on the ways in which experienced and less-experienced writers make use of the Academic

Phrasebank. Another project is seeking to find out more about ways in which teachers of English for

academic purposes make use of this resource.

References and related reading

• Bolinger, D. (1976) ‘Meaning and memory’. Forum Linguisticum, 1, pp. 1–14.

• Cowie, A. (1992) ‘Multiword lexical units and communicative language teaching’ in

Vocabulary and applied linguistics, Arnaud, P. and Béjoint, H. (eds). London: MacMillan.

• Davis, M., and Morley, J. (2015) ‘Phrasal intertextuality: The responses of academics from

different disciplines to students’ re-use of phrases’. Journal Second Language Writing 28 (2),

pp. 20-35.

• Hopkins, A. and Dudley-Evans, A. (1988). ‘A genre-based investigations of the discussions

sections in articles and dissertation’. English for Specific Purposes, 7(2), pp.113-122.

• Pawley, A., and Syder, F.H. (1983). ‘Two puzzles for linguistic theory: nativelike selection and

nativelike fluency’. In: Richards, J.C. and Schmidt, R.W. (Eds.), Language and communication,

pp. 191-226. Longman: New York.

• Sinclair, J. (1991) Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

• Swales, J. (1981). Aspects of article introductions (Aston ESP Research Report No. 1).

Birmingham: Language Studies Unit: University of Aston.

• Swales, J. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

• Wood, D. (2015) The fundamentals of formulaic language. London: Bloomsbury.

• Wray, A., and Perkins, M. (2000). ‘The functions of formulaic language: an integrated model’.

Language and Communication, 20, pp.1-28.

5 | P a g e

�

Major Sections

6 | P a g e

�

Introducing Work

There are many ways to introduce an academic essay or short paper. Most academic writers,

however, appear to do one or more of the following in their introductions:

indicate an issue, problem, or controversy in the field of study

• establish the context, background and/or importance of the topic

•

• define the topic or key terms

•

• provide an overview of the coverage and/or structure of the writing

state the purpose of the essay or piece of writing

Slightly less complex introductions may simply inform the reader: what the topic is, why it is

important, and how the writing is organised. In very short assignments, it is not uncommon for a

writer to commence simply by stating the purpose of their writing and by indicating how it is

organised.

Introductions to research dissertations and theses tend to be relatively short compared to the other

sections of the text but quite complex in terms of their functional elements. Some of the more

common elements include:

identifying a problem, controversy or a knowledge gap in the field of study

stating the aim(s) of the research and the research questions or hypotheses

• establishing the context, background and/or importance of the topic

• giving a brief review of the relevant academic literature

•

•

• providing a synopsis of the research design and method(s)

• explaining the significance or value of the study

• defining certain key terms

• providing an overview of the dissertation or report structure

Examples of phrases which are commonly employed to realise these and other functions are listed

under the headings that follow. Note that there may be a certain amount of overlap between some

of the categories under which the phrases are listed. Also, the order in which the different

categories of phrases are shown reflects a typical order but this is far from fixed or rigid, and not all

the elements are present in all introductions.

A number of analysts have identified common patterns in the introductions of research articles.

One of the best known is the CARS model (create a research space) first described by John Swales

(1990)1. This model, which utilises an ecological metaphor, has, in its simplest form, three elements

or moves:

• Establishing the territory (establishing importance of the topic, reviewing previous work)

•

• Occupying the niche (listing purpose of new research, listing questions, stating value,

Identifying a niche (indicating a gap in knowledge)

indicating structure of writing)

1 Swales, J. (1990) Genre Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

7 | P a g e

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc