Eur. Phys. J. C (2020) 80:326

https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-020-7881-2

Letter

Gravitational waves with orbital angular momentum

Pratyusava Baral1,a, Anarya Ray2,b, Ratna Koley1,c

1 Department of Physics, Presidency University, Kolkata 700073, India

2 Department of Physics, University of Winsconsin, Milwaukee 53211, USA

3 School of Physical Sciences, Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science, Kolkata 700032, India

, Parthasarathi Majumdar3,d

Received: 4 October 2019 / Accepted: 27 March 2020

© The Author(s) 2020

Abstract Compact orbiting binaries like the black hole

binary system observed in GW150914 carry large amount

of orbital angular momentum. The post-ringdown compact

object formed after merger of such a binary configuration

has only spin angular momentum, and this results in a large

orbital angular momentum excess. One significant possibility

is that the gravitational waves generated by the system carry

away this excess orbital angular momentum. An estimate of

this excess is made. Arguing that plane gravitational waves

cannot possibly carry any orbital angular momentum, a case

is made in this paper for gravitational wave beams carrying

orbital angular momentum, akin to optical beams. Restrict-

ing to certain specific beam-configurations, we predict that

such beams may produce a new type of strain, in addition to

the longitudinal strains measured at aLIGO for GW150914

and GW170817. Current constraints on post-ringdown spins,

derived within the plane-wave approximation of gravitational

waves, therefore stand to improve. The minimal modification

that might be needed on a laser-interferometer detector (like

aLIGO or VIRGO) to detect such additional strains is also

briefly discussed.

1 Introduction

Gravitational waves (GWs) detected by the Advanced Laser

Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (aLIGO) [1–

3] have established the existence of inspiralling compact

object binaries. Within General Relativity (GR), such sys-

tems radiate gravitational waves, carrying energy and angular

momenta [4,5], while spiraling into each other. The amount

of angular momentum carried, as viewed by an observer at

infinity (assuming the space-time to be asymptotically flat)

a e-mail: baralpratyusava@gmail.com

b e-mail: ronanarya9988@gmail.com

c e-mail: ratna.physics@presiuniv.ac.in (corresponding author)

d e-mail: bhpartha@gmail.com

can be estimated by the difference in angular momentum of

the initial and final stages of a merger. GW150914 confirmed

the merger of two black holes separated by a radius of 210 km

and of masses around 36 M and 29 M, forming a resul-

tant Kerr black hole of mass ∼ 62 M and a spin parameter

of ∼ 0.67 [1]. We estimate the rate of loss of orbital angular

momentum by the coalescing binary, assuming the objects to

be slowly moving, such that the quadrupole approximation

to gravitational wave generation still holds. In this approxi-

mation, the rate of loss of orbital angular momentum can be

given as

d�r 2˙habx j ∂khab

Qka

...

d Li

dt

= c3

32π G

= 2G

15c5

2G

15c5

�i jk

�i jk ¨Q ja

(μr 2)2ω5

(1)

Inserting typical values for the masses (∼ 30 M) and the

size of the compact binary (∼ 200 km), with the rotational

angular frequency of about 10 Hz, the rate of loss of orbital

angular momentum from the system is about 1034 Joules—

which is quite large. An actual estimate of orbital angular

momentum radiated closer to merger would include higher

order modes and thus increase the number. From such an esti-

mate, the motivations for a serious analysis towards the possi-

bility of detection of such a large orbital angular momentum,

carried by the gravitational waves, in current and forthcom-

ing laser interferometer experiments are very strong.

Measuring spacetime fluctuations as a function of time

only, aLIGO has successfully constrained source parame-

ters from which one can calculate radiated angular momen-

tum [9–11]. However a subtle issue arises if we want direct

measurement of angular momentum at some future detec-

tor. As we show in the sequel, monochromatic plane waves

with spatially constant polarizations, used predominantly in

detection analysis, cannot carry orbital angular momentum.

0123456789().: V,-vol

123

�

326 Page 2 of 7

Eur. Phys. J. C (2020) 80:326

Specifically, gravitational waves cannot reach the detector as

monochromatic plane waves due to angular momentum con-

servation. We stress that by the term ‘plane wave’ we mean, a

monochromatic wave solution of the linearized, source-free

Einstein equation, not only whose constant phase surfaces

are planes in spacetime, but also whose polarizations are spa-

tially constant, as the wave propagates. Taking a clue from

well established results in optics [12–16], we propose gravi-

tational radiation with some phase structure or gravitational

wave beams as a basis for expansion of the source wave-

form for detection analysis. The phase structure would enable

us to measure orbital angular momentum directly. Recently,

radiation from a spiralling charged particle [17,18] carrying

orbital angular momentum in the context of classical electro-

dynamics, has been shown to possess a similar phase struc-

ture.

There exist other motivational aspects of directly measur-

ing angular momentum from gravitational waves. A direct

measurement of orbital angular momentum would provide

us with an estimate of its rate of loss from the inspiralling

binary. This, in turn, might allow us to impose additional

constraints on the parameters over and above those obtained

by cross-correlation with various templates. This would fur-

ther enable us to settle many controversies relating to various

mergers [20] like GW170817 [3] (NS–NS merger) which are

expected to be routine in the near future. Using this, we may

also expect to put constraints on the exotic alternative com-

pact objects like fuzz balls [21], gravastars [22,23], worm-

holes [24], boson stars [25] and so on, and hence be able

to ascertain better the actual composition of the coalescing

binary. Comparing how well the estimated angular momen-

tum loss of the system compares to the angular momen-

tum carried by gravitational waves as detected by a faraway

observer, additional restrictions on the validity of GR in the

linearized regime may perhaps be ascertained. Lastly, the

third-generation run of the aLIGO and VIRGO is expected to

detect certain gravitational lensing events [19]. An additional

probe of angular momentum is expected to give us additional

knowledge of the medium through which it passes. This may

vastly improve our understanding of interactions of gravita-

tional waves with matter as it passes through astrophysical

objects such as stars or galactic clusters. However for the

time-being, we focus on a direct independent study of orbital

angular momentum carried by gravitational waves.

In this paper we examine the analytic structure of grav-

itational waves in the linearized regime, starting from the

gauge fixed linearized vacuum Einstein equation. We further

demand solutions that carry orbital angular momentum (We

prove that plane waves do not carry orbital angular momen-

tum in the next section). This naturally enables us to go

beyond plane waves and discuss gravitational wave beams.

However our solutions are well within the regime of Gen-

eral Relativity and does not take any modified gravity effect

123

into account. We show en passant that plane waves cannot

carry orbital angular momentum, implying that recourse to

gravitational wave beams is imperative. We choose a par-

ticular set of linearly independent beams which form a basis

for gravitational waves with orbital angular momentum. Any

gravitational radiation generated by sources within general

relativity can be expanded in this beam basis. A brief dis-

cussion is presented on the effects these beams would have

on spacetime. We also give a schematic outline, how these

beams carrying orbital angular momentum may be detected

and the contribution of the beam to the overall signal mea-

sured in a generic Laser-interferometer gravitational wave

detector.

2 Gravitational wave beams

We employ here the linearized tetrad formalism [27] for dis-

cussing gravitational waves, for two reasons: the ease to dis-

cuss fermionic interactions in astrophysically relevant quan-

tum field theoretic analysis, and to understand better the tran-

sition from local Lorentz invariance to global Lorentz sym-

metry under linearization—a phenomenon which remains

slightly obscure within the metric formalism. However, the

prescription to change to metric computations is included,

for the ease of the readers.

For the purpose of linearization, the spacetime tetrad com-

a are decomposed as eμa = eμa + εμa, where

ponents eμ

eμa is the background Minkowski spacetime tetrad and

as, ea

εμa is the linear fluctuation. Linearized gravity in the har-

monic gauge using this perturbed tetrad can be expressed

ν2εaμ = 0 where Greek indices specify

spacetime labels and early Latin indices are tangent space

labels. The late Latin indices are reserved for three dimen-

sional space. Therefore, the metric and fluctuations turns out

to be

μ2εaν +ea

ημν = ηabea

μeb

μεaν +ea

hμν =ea

ν

ν εaμ + O(ε2)

(2)

(3)

Equation (3) explicitly states how to transform from the met-

ric fluctuations to the tetrad fluctuations and vice-versa.

The gauge fixed linearized tetrad equation admits a wave

like solution given by,

εaμ = ϑaμ(x σ ) exp(ikλx λ) + ϑ∗

aμ(x σ ) exp(−ikλx λ)

(4)

∗

) representing complex conjugation. This

with the asterisk (

solution imposed on linearized tetrad equation gives,

(∂ ν ∂ν + 2ikν ∂ ν ) ϑaμ(x) = 0.

(5)

�

Eur. Phys. J. C (2020) 80:326

Page 3 of 7 326

The Lagrangian density and the energy-momentum tensor

for linearized gravity [28] are

L = − c4

32π G

T μν = c4

16π G

(∂ μεaσ ∂μεaσ +ea

(∂ μεaσ ∂ ν εaσ +ea

σebρ ∂ μεaρ ∂μεb

σebρ ∂ μεaρ ∂ ν εb

σ )

σ )

(6)

(7)

Since we are dealing with small fluctuations around a

Minkowski spacetime tetrad in the linearized region, the sys-

tem is globally Lorentz-symmetric. The conserved Noether

charge density corresponding to this symmetry can be

expressed as,

Mρσ = ˙εaμ[x[ρ|(∂|σ]εaμ +ea

νebμ∂|σ]εb

ν )]

(8)

8π G

c2

where, over dot represents time derivative, and the square

brackets denote anti-symmetry. Integrating this charge den-

sity over all space gives the infinitesimal Lorentz generators.

If ϑaμ is not a function of the spatial coordinates (xi )

(xi k j −

on integration the first term reduces to terms like

x j ki )d3x; with the integration measure being clearly rota-

tionally invariant, the first term vanishes by spatial rotational

invariance ! This implies that a spatially constant polariza-

tion, like for plane waves in our connotation [which definitely

satisfy Eq. (5)], cannot carry orbital angular momentum. It

follows that for gravitational waves to carry orbital angular

momentum, their polarization tensors must themselves be

tensor fields. One way to enable polarization fields in grav-

itational waves is through gravitational wave beams, akin

to optical beams. Plane waves definitely carry spin angu-

lar momentum. But the spin angular momentum density

is miniscule, and definitely cannot account for all angular

momentum radiated. Moreover the spin part is a property of

the radiation and can never be zero for a rank two tensor

field. The orbital angular momentum is dependent on orien-

tation of objects and fields and thus somewhat arbitrary. Thus

there is no reason to expect that orbital angular momentum

of source is getting converted to spin angular momentum of

the wave. Thus we are looking for the most general solution

of linearized vacuum Einstein field equations.

2.1 Laguerre–Gaussian (LG) beams

Let z direction be the direction of propagation of the grav-

itational wave beam. Since any conceivable detector has to

be placed far away from the sources, we can safely assume

the beam to be paraxial (kz ≈ k) [14,15]. So Eq. 5 can be

expressed as

(∇T

where ∇T

2 is a two dimensional Laplace operator in the

plane perpendicular to z. The paraxial approximation also

guarantees that the change in polarization tensor in the

2 + ∂ z∂z − ∂t ∂t + 2ikz∂ z − 2ikt ∂t ) ϑaμ(x) = 0

(9)

r 2

T = 1

r

∂2ϑ aμ

kz

direction of propagation is negligible in comparison to the

. So Eq. (9) reduces to,

wave vector

(∇T

2+ 2ikz∂ z) ϑaμ(x) = 0. We choose the transverse plane

∂r + ∂r

to be spanned by (r, φ) then ∇2

2 + 1

∂ϑ aμ

∂z2

∂φ

2.

∂z

For simplicity, we choose to work with one particular com-

ponent of ϑaμ and for the time being we drop the spacetime

and tangent space indices.

A solution of the form

√

−ikr 2z

2r

2(z2 + z2

w(z)

imφ − i (2 p + |m| + 1) tan

−r 2

ϑmp(r, φ, z) = Amp

w(z)

× exp

× exp

|m|

p

2r 2

w2(z)

−1 z

z R

|m|

exp

(10)

L

R

)

w2(z)

λ

2π

z

z R

2

λ . L

where

and k ≈ kz = 2π

satisfies Eq. (9) in its paraxial form [15] with m, p taking

integer values referring to various modes. The radius of the

1 +

beam w(z) is given by w(z) = w(0)

|m|

z R = π w(0)

p (x) is the associated

Laguerre polynomial while Amp is a normalization constant.

By definition of Laguerre polynomials, p has to be an integer.

The single valuedness of the field under a rotation of π radian

forces the azimuthally dependent phase factor to be quantized

with m taking only integral values. The Laguerre–Gaussian

modes are orthonormal in both labels m & p such that

rdr ϑmp(r, φ, z)[ϑqr (r, φ, z)]∗ = δmq δ pr .

∞

0

This guarantees that the LG modes form a complete orthonor-

mal family which can be used as a basis for a beam with

an arbitrary polarization distribution. These beams exhibit

a symmetry manifest in the use of cylindrical coordinates.

Any other choice of a complete set of beams a different sym-

metry (like, e.g., the Bessel beam) is equally valid; these

beams can of course be expressed as a linear combination of

LG modes. Since our solutions form a basis, any waveform

including plane waves or spherical waves can be expanded

in our basis.

dφ

0

The orbital angular momentum density can be expressed

in a simple form which follows directly from Eq. (8),

L =

d3x

− l

ω

|ϑmp|2ˆr + r

c

z

r

+ l

ω

|ϑmp|2ˆz

− 1

|ϑmp|2 ˆφ

z2

z2+z2

R

(11)

Such solutions also exist in the case of electromagnetic

waves and have been extensively studied in Refs. [12–

16]. Bialynicki-Birula et al. [29] have also discussed GW

beams using an electromagnetic-gravitational correspon-

dence within a spinoral formalism. In this work we take an

123

�

326 Page 4 of 7

Eur. Phys. J. C (2020) 80:326

approach that appears to be more convenient for phenomeno-

logical applications.

Integrating the angular momentum density (11) over all

space, we get the total angular momentum. As stated earlier

our analysis is only valid in the weak field regime. So, the

integration domain must be restricted to that regime. Here we

should mention the caveat that unlike in laser optics, w(0)

has no significance and is just a free parameter of the chosen

basis.

3 Effect of a passing gravitational wave beam on

spacetime: possible detection

Fig. 1 A ring of masses in presence and absence of GWs

εa

εa

εb

x

x + eb

x

y + eb

y

x and h× = ea

We first describe the effect on spacetime in the plane per-

pendicular to the direction of propagation. Let this trans-

verse plane be spanned by coordinates x, y. It is well known

that in standard TT gauge all perturbation except h+ =

ea

εb

x can be gauged

x

away to 0. To start with let us consider a gravitational wave

beam consisting of only the component h+ . The correspond-

ing tetrad fluctuation εaμ=x contains an infinite number of

various LG modes. The proper distance between four test

particles localized at A(0, 0), B(L , 0), C(L , L) and D(0, L)

would change due to the passing gravitational wave. Firstly

let us consider motion along or parallel to x-axis. Therefore,

dt 2 = dy2 = dz2 = 0.

ds2 = (1 + 2ea

ea

⇒ �l

⇒ �l =

(C + g(y))dx

εax dx f (y)

εax )dx 2

l

l

0

0

(12)

(13)

x

x

l

= Cl +

g(y)dx

0

(14)

f (y) and g(y) are functions of y differing with a

where,

constant value of C.

The decomposition of the integral into two parts, one

involving a constant C which is the dominant plane wave con-

tribution; the sub-dominant contribution is due to the beam

structure. The first term gives normal longitudinal strain as

expected by plane waves and the second is a non-longitudinal

term. The second term which is essentially due to deviation

from plane waves carry all information about radiated angu-

lar momentum giving rise to various new non-trivial effects.

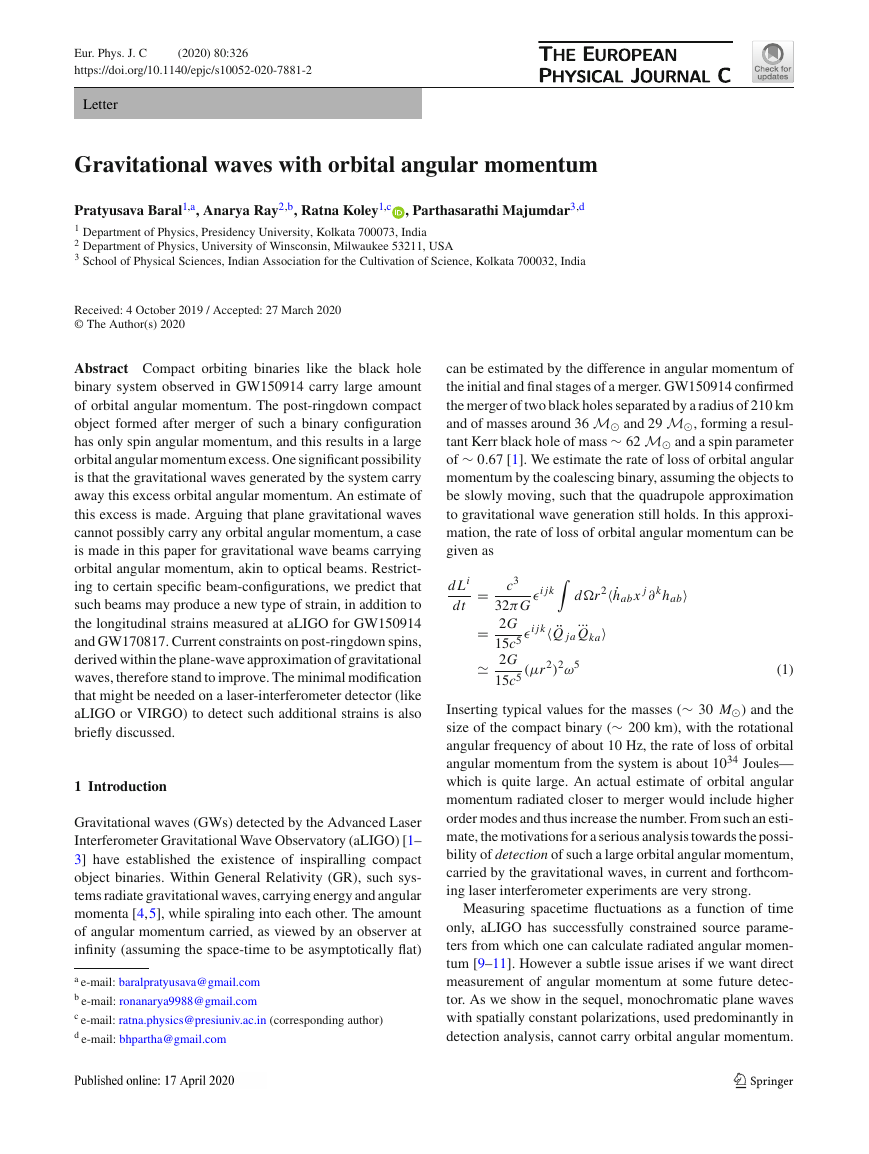

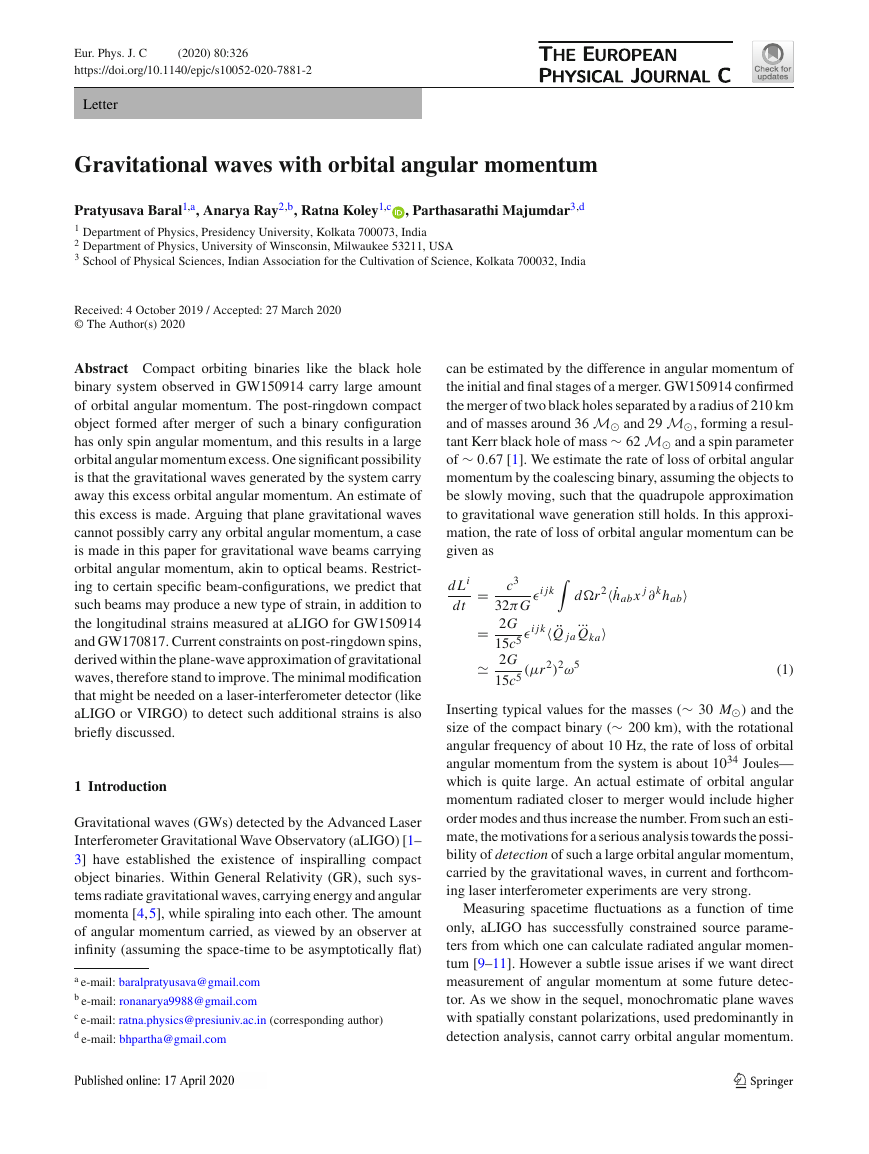

If a gravitational wave of constant polarization passes over

a circular ring of particles (shown by bold green dots), they

would change to an elliptical ring (shown by red dots) as

shown in Fig. 1.

The presence of a LG mode would deviate the masses

from their expected places (shown by blue crosses) due to the

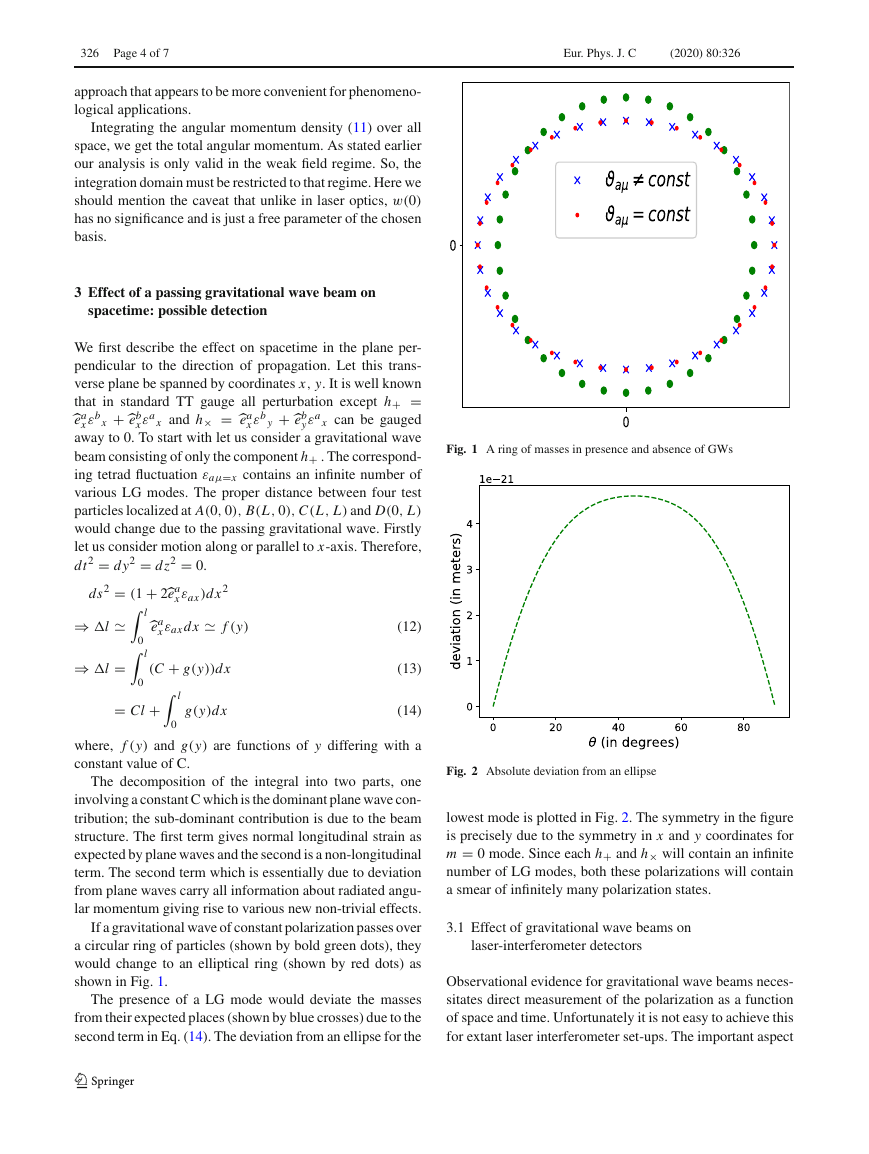

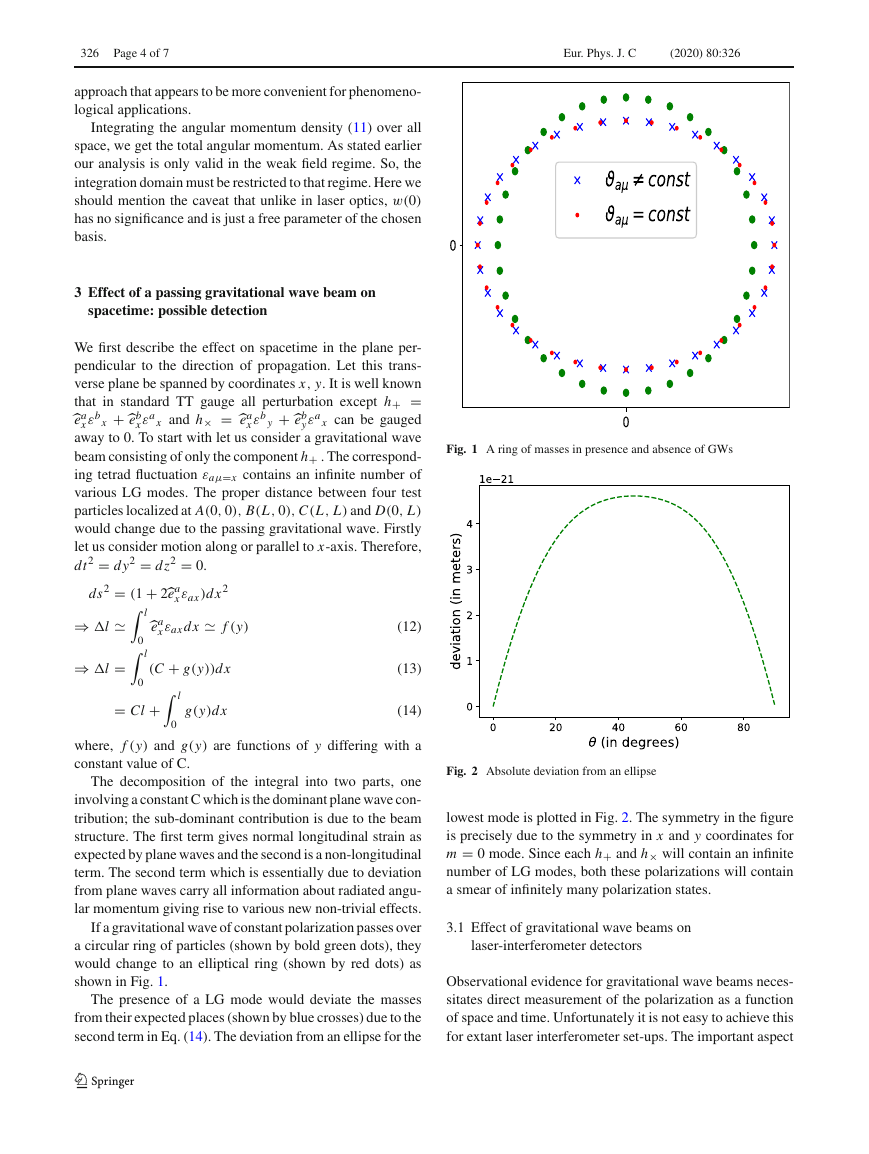

second term in Eq. (14). The deviation from an ellipse for the

123

Fig. 2 Absolute deviation from an ellipse

lowest mode is plotted in Fig. 2. The symmetry in the figure

is precisely due to the symmetry in x and y coordinates for

m = 0 mode. Since each h+ and h× will contain an infinite

number of LG modes, both these polarizations will contain

a smear of infinitely many polarization states.

3.1 Effect of gravitational wave beams on

laser-interferometer detectors

Observational evidence for gravitational wave beams neces-

sitates direct measurement of the polarization as a function

of space and time. Unfortunately it is not easy to achieve this

for extant laser interferometer set-ups. The important aspect

�

Eur. Phys. J. C (2020) 80:326

Page 5 of 7 326

is that the change in the length of an interferometer arm is no

longer a simple linear function of its original length, if the

interferometer is exposed to a gravitational wave beam. This

departure from linearity can be exploited to infer informa-

tion about possible orbital angular momentum of the incident

gravitational wave.

We shall now attempt to assess the effect of gravitational

wave beams with the stated polarization profile on laser inter-

ferometer detectors. Let the plane of the detector be spanned

by x, y coordinates and the direction of propagation make

an arbitrary angle with the z-axis. This detector will mea-

sure the intensity of the component of the incoming beam of

gravitational waves along the z direction.

εb

εb

x

εa

x

x+eb

x +eb

y+eb

the x y plane, ds2 = c2dt 2− dx 2{1+ (ea

For laser beams travelling along the arms of a detector in

x )ηab}−

dy2{1−(ea

x )ηab}−dxdy(ea

x )ηab = 0.

x

εb

Now for the x-arm (length = L), y = 0 = dy, and for the

y-arm (length = L), x = 0 = dx. Thus,

εax|y=0 ≈ dx(1 +ea

cdtx = dx

1 + 2ea

εax|y=0)

(15)

εa

x

εa

y

x

x

x

c

Using Eq. (4) and putting t = x

c or t = y

c for the for-

and L+y

ward journey and t = L+x

ney, [30] we get: τx = 2L +

for the return jour-

ea

(ϑax (x, 0, z)eik(z−x) +

−ik(z−x))dx+

ea

(ϑax (x, 0, z)eik(z−(L+x))+

ϑ∗

−ik(z−(L+x)))dx.

ϑ∗

(x, 0, z)e

ax

(x, 0, z)e

ax

Similar equations hold for the y-direction. Now we can

calculate the phase difference between the x and y arm light

rays:

L

0

L

0

c

x

x

δφ (L) = 2π(τx − τy)

λlight

= f (L) ≈ α + β L + γ L2

(16)

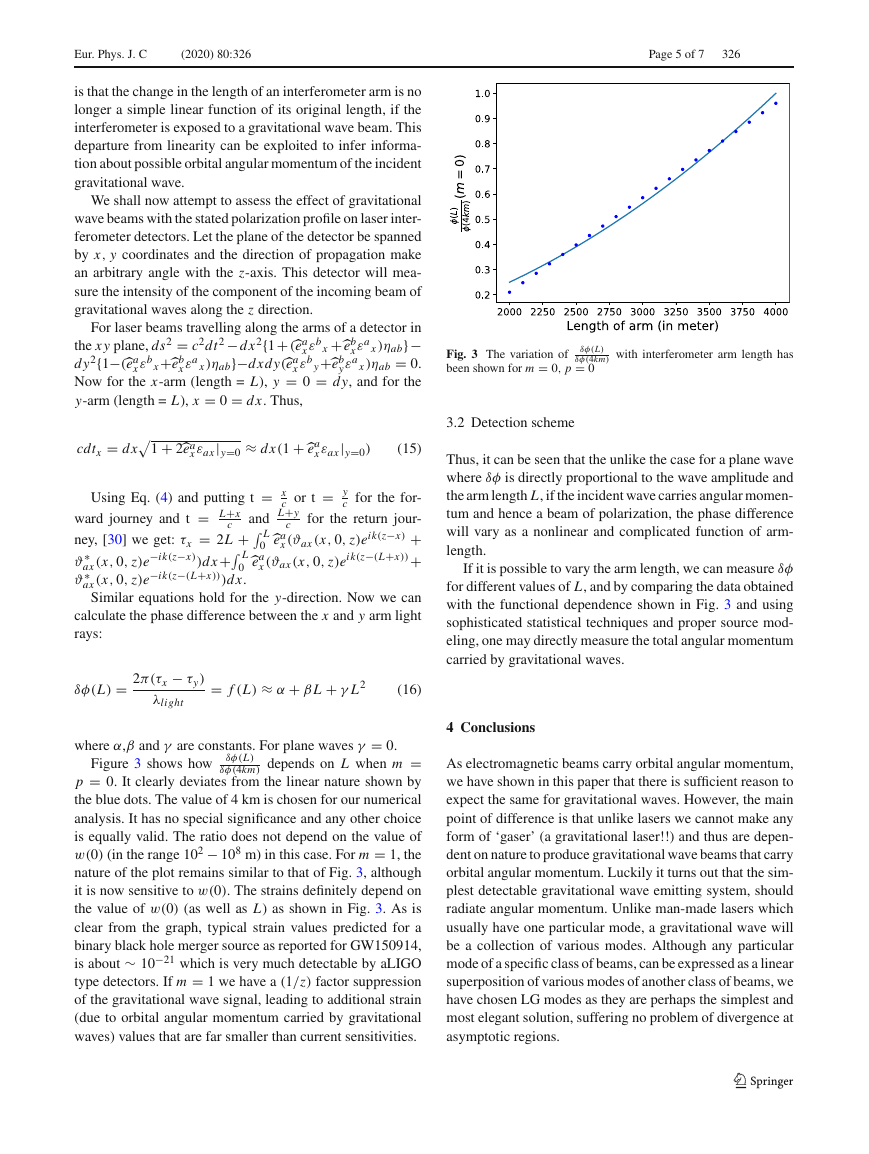

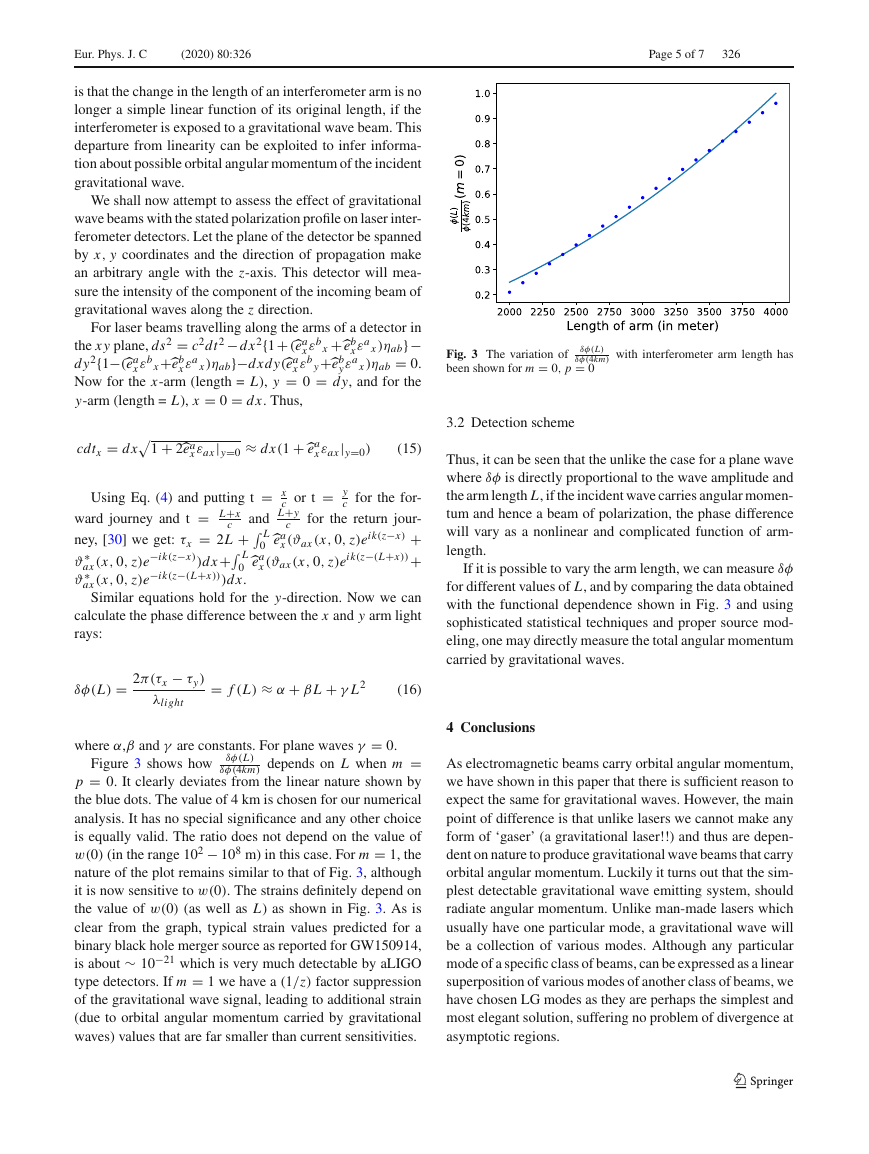

where α,β and γ are constants. For plane waves γ = 0.

δφ (4km) depends on L when m =

Figure 3 shows how δφ (L)

p = 0. It clearly deviates from the linear nature shown by

the blue dots. The value of 4 km is chosen for our numerical

analysis. It has no special significance and any other choice

is equally valid. The ratio does not depend on the value of

w(0) (in the range 102 − 108 m) in this case. For m = 1, the

nature of the plot remains similar to that of Fig. 3, although

it is now sensitive to w(0). The strains definitely depend on

the value of w(0) (as well as L) as shown in Fig. 3. As is

clear from the graph, typical strain values predicted for a

binary black hole merger source as reported for GW150914,

is about ∼ 10

−21 which is very much detectable by aLIGO

type detectors. If m = 1 we have a (1/z) factor suppression

of the gravitational wave signal, leading to additional strain

(due to orbital angular momentum carried by gravitational

waves) values that are far smaller than current sensitivities.

Fig. 3 The variation of

been shown for m = 0, p = 0

δφ (L)

δφ (4km) with interferometer arm length has

3.2 Detection scheme

Thus, it can be seen that the unlike the case for a plane wave

where δφ is directly proportional to the wave amplitude and

the arm length L, if the incident wave carries angular momen-

tum and hence a beam of polarization, the phase difference

will vary as a nonlinear and complicated function of arm-

length.

If it is possible to vary the arm length, we can measure δφ

for different values of L, and by comparing the data obtained

with the functional dependence shown in Fig. 3 and using

sophisticated statistical techniques and proper source mod-

eling, one may directly measure the total angular momentum

carried by gravitational waves.

4 Conclusions

As electromagnetic beams carry orbital angular momentum,

we have shown in this paper that there is sufficient reason to

expect the same for gravitational waves. However, the main

point of difference is that unlike lasers we cannot make any

form of ‘gaser’ (a gravitational laser!!) and thus are depen-

dent on nature to produce gravitational wave beams that carry

orbital angular momentum. Luckily it turns out that the sim-

plest detectable gravitational wave emitting system, should

radiate angular momentum. Unlike man-made lasers which

usually have one particular mode, a gravitational wave will

be a collection of various modes. Although any particular

mode of a specific class of beams, can be expressed as a linear

superposition of various modes of another class of beams, we

have chosen LG modes as they are perhaps the simplest and

most elegant solution, suffering no problem of divergence at

asymptotic regions.

123

�

326 Page 6 of 7

Eur. Phys. J. C (2020) 80:326

In this paper, in addition to showing the necessity of con-

sidering gravitational wave beams in place of plane waves

in order to explain the orbital angular momentum emitted

via gravitational waves, by the merger of inspiralling com-

pact binaries, we have presented an account of the effects

these gravitational wave beams will have on spacetime in

general and on laser interferometer detectors. Further, per-

haps for the first time, we have proposed a schematic way

of measuring the phase structure of gravitational radiation,

by incorporating minimal changes in extant interferometers.

Since the orbital angular momentum of gravitational waves

can be directly calculated from these amplitudes, we have

thus, again for the first time, proposed a schematic method

of direct measurement of angular momentum carried by grav-

itational waves.

We are primarily interested in the lowest order mode,

because the first higher mode for GW150914 like sources

will have non-unique values of strains dependent on the

normalization factor w(0) and primarily because we have

a 1/zm-suppression. This might make the interference signal

too weak to detect. Having said that though, the expressions

are dependent on various non-linear parameters and a par-

ticular set of w(0); tweaking the frequency and distance it

may be possible to produce such additional strains for higher

modes, which are more realistic.

The idea of gravitational wave beams is at its infancy and

thus lot of work remains to be done. From the values of the

plus and cross polarizations at asymptotic regions obtained

from various numerical simulations one might try to estimate

various beam parameters. Since the beams form a complete

basis, any wave form predicted by numerical relativity can

always be expanded in terms of the beams by computing

the overlap integrals and the corresponding beam parameters

measured via the scheme discussed in this paper. This would

enable us to understand if data from a fixed length detector

is sufficient to determine the beam parameters uniquely with

a little degeneracy. Although this work is yet to be done, our

intuition suggests that the deviation from plane waves will

not become apparent due to their smallness until we have

some way to vary the length of detectors. However a more

rigorous calculation is left to be done before making any

concrete statement.

Moreover the solution presented here involves the paraxial

approximation. It is possible to get exact solutions of the

vacuum linearized Einstein’s equations beyond the paraxial

approximation, which still carry orbital angular momentum

and form a complete basis. This is currently under study.

Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Soumendra

Kishore Roy and Sk. Sajid of Presidency University, Kolkata for valu-

able discussions and inputs. R. Koley acknowledges WBDHESTBT

research fund. PB and AR would like to thank Bala Iyer of ICTS, K. G.

Arun and J. Haque of CMI,India and A. Gupta of Pennsylvania State

University for discussions in the IAGRG meeting 2018. PB is grateful

123

to Luc Blanchet for a discussion at the 2019 ICTS Summer School on

Gravitational Waves regarding total orbital angular momentum radiated

away through gravitational waves.

Data Availability Statement This manuscript has no associated data

or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: Since we have

a complete basis any waveform (including plane waveform) can be

described using our solution. So in principle using the present LIGO-

Virgo detectors we can estimate our beam parameters. But the issue

that needs to be checked is if the parameter space is degenerate or not.

Moreover increasing number of parameters will naturally improve the

likelihood function, and thus one requires detailed statistical analysis

of the parameters before blindly estimating it. We plan to work on this

in the near future and hope to come up with a more concrete statement

on the detectability of beam parameters from fixed length detectors.]

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attri-

bution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation,

distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you

give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, pro-

vide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes

were made. The images or other third party material in this article

are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indi-

cated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not

included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended

use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permit-

ted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copy-

right holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecomm

ons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Funded by SCOAP3.

References

1. B.P. Abbott et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 241102 (2016).

arXiv:1610.02182 [gr-qc]

2. B.P. Abbott et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 221101 (2017).

arXiv:1706.01812 [gr-qc]

3. B.P. Abbott et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 161101 (2017).

arXiv:1710.05832 [gr-qc]

4. A. Einstein, Sitzungsber. K. Preuss. Akad. Wiss. 1, 688 (1916)

5. A. Einstein, Sitzungsber. K. Preuss. Akad. Wiss 1, 154 (1918)

6. S. Stevenson et al., Nat Commun. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/

ncomms14906 arXiv:1704.01352 [astro-ph.HE]

7. I. Mandel, A. Farmer. arXiv:1806.05820 [astro-ph.HE]

8. I. Bialynicki-Birula, S. Charzy´nski, Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 171101

(2018). arXiv:1810.02219 [gr-qc]

9. K. Thorne, Rev. Mod. Phys. 52, 299 (1980)

10. T.W. Baumgarte, S.L. Shapiro, Numerical Relativity: Solving Ein-

stein’s Equations on the Computer, 1st edn. (Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge, 2010)

11. M. Shibata, Numerical Relativity (100 Years of General Relativity)

(World Scientific Publishing Company, New York, 2015)

12. L. Allen et al., Phys. Rev. A 45(11), 8185–8190 (1992). (reprinted

in [57, Paper 2.1])

13. A.M. Yao, M.J. Padgett, Adv. Opt. Phot. 3, 161 (2011)

14. J.B. Gotte, S.M. Barnett, in Light Beams Carrying Orbital Angular

Momentum, ed. by Andrews, D., Babiker, M. The Angular Momen-

tun of Light, 1st edn. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

2013)

15. H.A. Haus, Waves and Fields in Optoelectronics (Chapter 5)

(Prentice-Hall Inc., New York, 1984)

16. D.S. Simon, A Guided Tour of Light Beams (Morgan & Claypool

Publishers (IOP concise physics), New York, 2016)

�

Eur. Phys. J. C (2020) 80:326

Page 7 of 7 326

17. M. Katoh et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 094801 (2017).

arXiv:1610.02182 [physics.optics]

18. V. Epp, U. Guselnikova, Phys. Lett. A 383(22), 2668–2671 (2019)

19. Christian et al., Phys. Rev. D 10, 103022 (2018). arXiv:1802.02586

28. M. Maggiore, in Gravitational Waves: Theory and Experiments.

Oxford Master Series in Physics, vol. 1 (Oxford University Press,

Oxford, 2007)

29. I. Bialynicki-Birula, Z. Bialynicka-Birula, New J. Phys. 18, 023022

[astro-ph.HE]

20. H. Yang et al., arXiv:1710.05891 [gr-qc]

21. S.D. Mathur,

Fortsch.

Phys.

53,

(2016). arXiv:1511.08909v1 [gr-qc]

30. B. Schutz, A First Course in General Relativity, 2nd edn. (Cam-

793–827

(2005).

bridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009)

arXiv:hep-th/0502050 [hep-th]

22. P. O. Mazur, E. Mottola, arXiv:gr-qc/109035 [gr-qc]

23. C. Chirenti, L. Rezzolla, Phys. Rev. D 94, 084016 (2016).

arXiv:1602.08759 [gr-qc]

24. T. Damour, S.N. Solodukhin, Phys. Rev. D 76, 024016 (2007).

arXiv:0704.2667 [gr-qc]

25. R. Ruffini, S. Bonazzola, Phys. Rev. 187, 1767–1783 (1969)

26. Z. Mark et al., Phys. Rev. D 96, 084002 (2017). arXiv:1706.06155

[gr-qc]

27. J. Yepez, arXiv:1106.2037 [gr-qc]

123

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc