To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

Our gain in net worth during 1988 was $569 million, or

20.0%. Over the last 24 years (that is, since present management

took over), our per-share book value has grown from $19.46 to

$2,974.52, or at a rate of 23.0% compounded annually.

We’ve emphasized in past reports that what counts, however,

is intrinsic business value - the figure, necessarily an

estimate, indicating what all of our constituent businesses are

worth. By our calculations, Berkshire’s intrinsic business value

significantly exceeds its book value. Over the 24 years,

business value has grown somewhat faster than book value; in

1988, however, book value grew the faster, by a bit.

Berkshire’s past rates of gain in both book value and

business value were achieved under circumstances far different

from those that now exist. Anyone ignoring these differences

makes the same mistake that a baseball manager would were he to

judge the future prospects of a 42-year-old center fielder on the

basis of his lifetime batting average.

Important negatives affecting our prospects today are: (1) a

less attractive stock market than generally existed over the past

24 years; (2) higher corporate tax rates on most forms of

investment income; (3) a far more richly-priced market for the

acquisition of businesses; and (4) industry conditions for

Capital Cities/ABC, Inc., GEICO Corporation, and The Washington

Post Company - Berkshire’s three permanent investments,

constituting about one-half of our net worth - that range from

slightly to materially less favorable than those existing five to

ten years ago. All of these companies have superb management and

strong properties. But, at current prices, their upside

potential looks considerably less exciting to us today than it

did some years ago.

The major problem we face, however, is a growing capital

base. You’ve heard that from us before, but this problem, like

age, grows in significance each year. (And also, just as with

age, it’s better to have this problem continue to grow rather

than to have it “solved.”)

Four years ago I told you that we needed profits of $3.9

billion to achieve a 15% annual return over the decade then

ahead. Today, for the next decade, a 15% return demands profits

of $10.3 billion. That seems like a very big number to me and to

Charlie Munger, Berkshire’s Vice Chairman and my partner. (Should

that number indeed prove too big, Charlie will find himself, in

future reports, retrospectively identified as the senior

partner.)

As a partial offset to the drag that our growing capital

base exerts upon returns, we have a very important advantage now

that we lacked 24 years ago. Then, all our capital was tied up

in a textile business with inescapably poor economic

characteristics. Today part of our capital is invested in some

really exceptional businesses.

Last year we dubbed these operations the Sainted Seven:

Buffalo News, Fechheimer, Kirby, Nebraska Furniture Mart, Scott

Fetzer Manufacturing Group, See’s, and World Book. In 1988 the

Saints came marching in. You can see just how extraordinary

their returns on capital were by examining the historical-cost

financial statements on page 45, which combine the figures of the

B

E

R

K

S

H

I

R

E

H

A

T

H

A

W

A

Y

I

N

C

.

�

Sainted Seven with those of several smaller units. With no

benefit from financial leverage, this group earned about 67% on

average equity capital.

In most cases the remarkable performance of these units

arises partially from an exceptional business franchise; in all

cases an exceptional management is a vital factor. The

contribution Charlie and I make is to leave these managers alone.

In my judgment, these businesses, in aggregate, will

continue to produce superb returns. We’ll need these: Without

this help Berkshire would not have a chance of achieving our 15%

goal. You can be sure that our operating managers will deliver;

the question mark in our future is whether Charlie and I can

effectively employ the funds that they generate.

In that respect, we took a step in the right direction early

in 1989 when we purchased an 80% interest in Borsheim’s, a

jewelry business in Omaha. This purchase, described later in

this letter, delivers exactly what we look for: an outstanding

business run by people we like, admire, and trust. It’s a great

way to start the year.

Accounting Changes

We have made a significant accounting change that was

mandated for 1988, and likely will have another to make in 1990.

When we move figures around from year to year, without any change

in economic reality, one of our always-thrilling discussions of

accounting is necessary.

First, I’ll offer my customary disclaimer: Despite the

shortcomings of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP),

I would hate to have the job of devising a better set of rules.

The limitations of the existing set, however, need not be

inhibiting: CEOs are free to treat GAAP statements as a beginning

rather than an end to their obligation to inform owners and

creditors - and indeed they should. After all, any manager of a

subsidiary company would find himself in hot water if he reported

barebones GAAP numbers that omitted key information needed by his

boss, the parent corporation’s CEO. Why, then, should the CEO

himself withhold information vitally useful to his bosses - the

shareholder-owners of the corporation?

What needs to be reported is data - whether GAAP, non-GAAP,

or extra-GAAP - that helps financially-literate readers answer

three key questions: (1) Approximately how much is this company

worth? (2) What is the likelihood that it can meet its future

obligations? and (3) How good a job are its managers doing, given

the hand they have been dealt?

In most cases, answers to one or more of these questions are

somewhere between difficult and impossible to glean from the

minimum GAAP presentation. The business world is simply too

complex for a single set of rules to effectively describe

economic reality for all enterprises, particularly those

operating in a wide variety of businesses, such as Berkshire.

Further complicating the problem is the fact that many

managements view GAAP not as a standard to be met, but as an

obstacle to overcome. Too often their accountants willingly

assist them. (“How much,” says the client, “is two plus two?”

Replies the cooperative accountant, “What number did you have in

mind?”) Even honest and well-intentioned managements sometimes

stretch GAAP a bit in order to present figures they think will

more appropriately describe their performance. Both the

smoothing of earnings and the “big bath” quarter are “white lie”

techniques employed by otherwise upright managements.

�

Then there are managers who actively use GAAP to deceive and

defraud. They know that many investors and creditors accept GAAP

results as gospel. So these charlatans interpret the rules

“imaginatively” and record business transactions in ways that

technically comply with GAAP but actually display an economic

illusion to the world.

As long as investors - including supposedly sophisticated

institutions - place fancy valuations on reported “earnings” that

march steadily upward, you can be sure that some managers and

promoters will exploit GAAP to produce such numbers, no matter

what the truth may be. Over the years, Charlie and I have

observed many accounting-based frauds of staggering size. Few of

the perpetrators have been punished; many have not even been

censured. It has been far safer to steal large sums with a pen

than small sums with a gun.

Under one major change mandated by GAAP for 1988, we have

been required to fully consolidate all our subsidiaries in our

balance sheet and earnings statement. In the past, Mutual

Savings and Loan, and Scott Fetzer Financial (a credit company

that primarily finances installment sales of World Book and Kirby

products) were consolidated on a “one-line” basis. That meant we

(1) showed our equity in their combined net worths as a single-

entry asset on Berkshire’s consolidated balance sheet and (2)

included our equity in their combined annual earnings as a

single-line income entry in our consolidated statement of

earnings. Now the rules require that we consolidate each asset

and liability of these companies in our balance sheet and each

item of their income and expense in our earnings statement.

This change underscores the need for companies also to

report segmented data: The greater the number of economically

diverse business operations lumped together in conventional

financial statements, the less useful those presentations are and

the less able investors are to answer the three questions posed

earlier. Indeed, the only reason we ever prepare consolidated

figures at Berkshire is to meet outside requirements. On the

other hand, Charlie and I constantly study our segment data.

Now that we are required to bundle more numbers in our GAAP

statements, we have decided to publish additional supplementary

information that we think will help you measure both business

value and managerial performance. (Berkshire’s ability to

discharge its obligations to creditors - the third question we

listed - should be obvious, whatever statements you examine.) In

these supplementary presentations, we will not necessarily follow

GAAP procedures, or even corporate structure. Rather, we will

attempt to lump major business activities in ways that aid

analysis but do not swamp you with detail. Our goal is to give

you important information in a form that we would wish to get it

if our roles were reversed.

On pages 41-47 we show separate combined balance sheets and

earnings statements for: (1) our subsidiaries engaged in finance-

type operations, which are Mutual Savings and Scott Fetzer

Financial; (2) our insurance operations, with their major

investment positions itemized; (3) our manufacturing, publishing

and retailing businesses, leaving aside certain non-operating

assets and purchase-price accounting adjustments; and (4) an all-

other category that includes the non-operating assets (primarily

marketable securities) held by the companies in (3) as well as

various assets and debts of the Wesco and Berkshire parent

companies.

If you combine the earnings and the net worths of these four

segments, you will derive totals matching those shown on our GAAP

statements. However, we want to emphasize that our new

presentation does not fall within the purview of our auditors,

�

who in no way bless it. (In fact, they may be horrified; I don’t

want to ask.)

I referred earlier to a major change in GAAP that is

expected in 1990. This change relates to the calculation of

deferred taxes, and is both complicated and controversial - so

much so that its imposition, originally scheduled for 1989, was

postponed for a year.

When implemented, the new rule will affect us in various

ways. Most important, we will be required to change the way we

calculate our liability for deferred taxes on the unrealized

appreciation of stocks held by our insurance companies.

Right now, our liability is layered. For the unrealized

appreciation that dates back to 1986 and earlier years, $1.2

billion, we have booked a 28% tax liability. For the unrealized

appreciation built up since, $600 million, the tax liability has

been booked at 34%. The difference reflects the increase in tax

rates that went into effect in 1987.

It now appears, however, that the new accounting rule will

require us to establish the entire liability at 34% in 1990,

taking the charge against our earnings. Assuming no change in

tax rates by 1990, this step will reduce our earnings in that

year (and thereby our reported net worth) by $71 million. The

proposed rule will also affect other items on our balance sheet,

but these changes will have only a minor impact on earnings and

net worth.

We have no strong views about the desirability of this

change in calculation of deferred taxes. We should point out,

however, that neither a 28% nor a 34% tax liability precisely

depicts economic reality at Berkshire since we have no plans to

sell the stocks in which we have the great bulk of our gains.

To those of you who are uninterested in accounting, I

apologize for this dissertation. I realize that many of you do

not pore over our figures, but instead hold Berkshire primarily

because you know that: (1) Charlie and I have the bulk of our

money in Berkshire; (2) we intend to run things so that your

gains or losses are in direct proportion to ours; and (3) the

record has so far been satisfactory. There is nothing

necessarily wrong with this kind of “faith” approach to

investing. Other shareholders, however, prefer an “analysis”

approach and we want to supply the information they need. In our

own investing, we search for situations in which both approaches

give us the same answer.

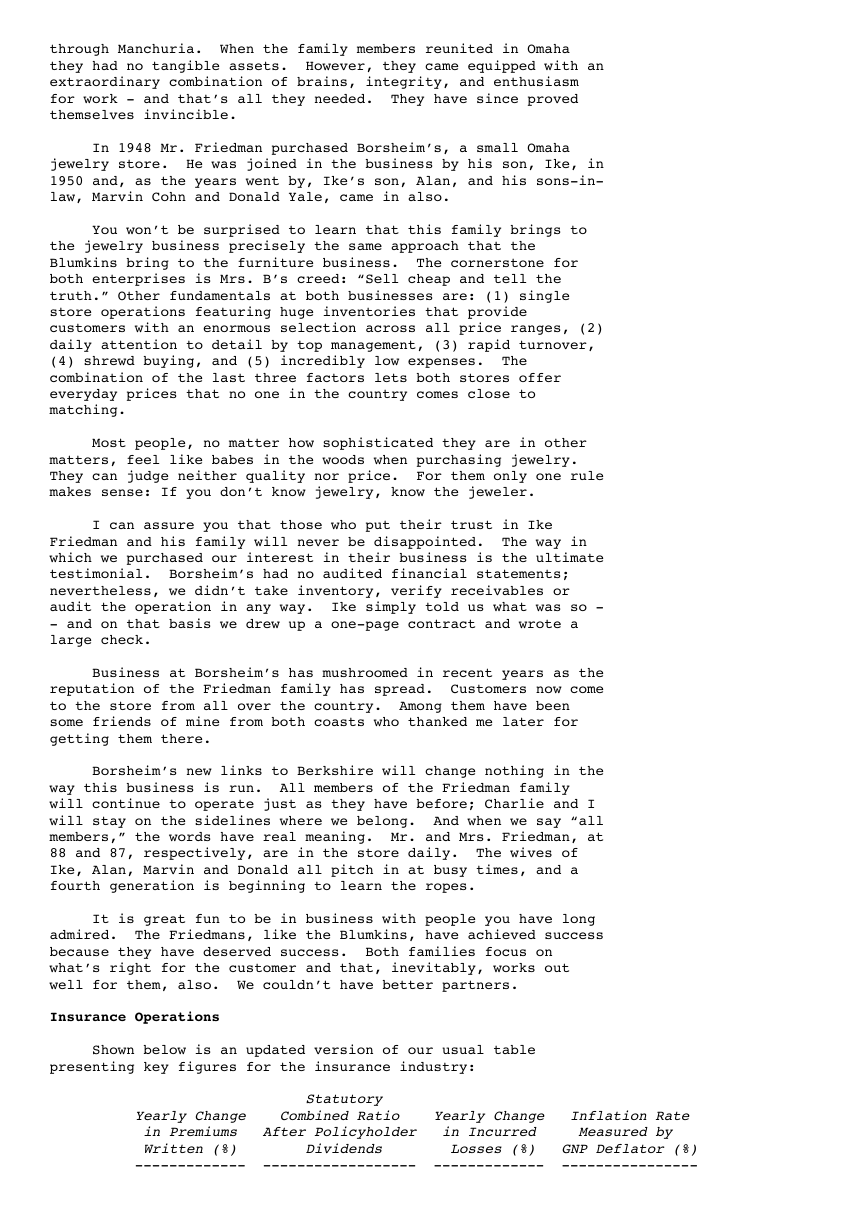

Sources of Reported Earnings

In addition to supplying you with our new four-sector

accounting material, we will continue to list the major sources

of Berkshire’s reported earnings just as we have in the past.

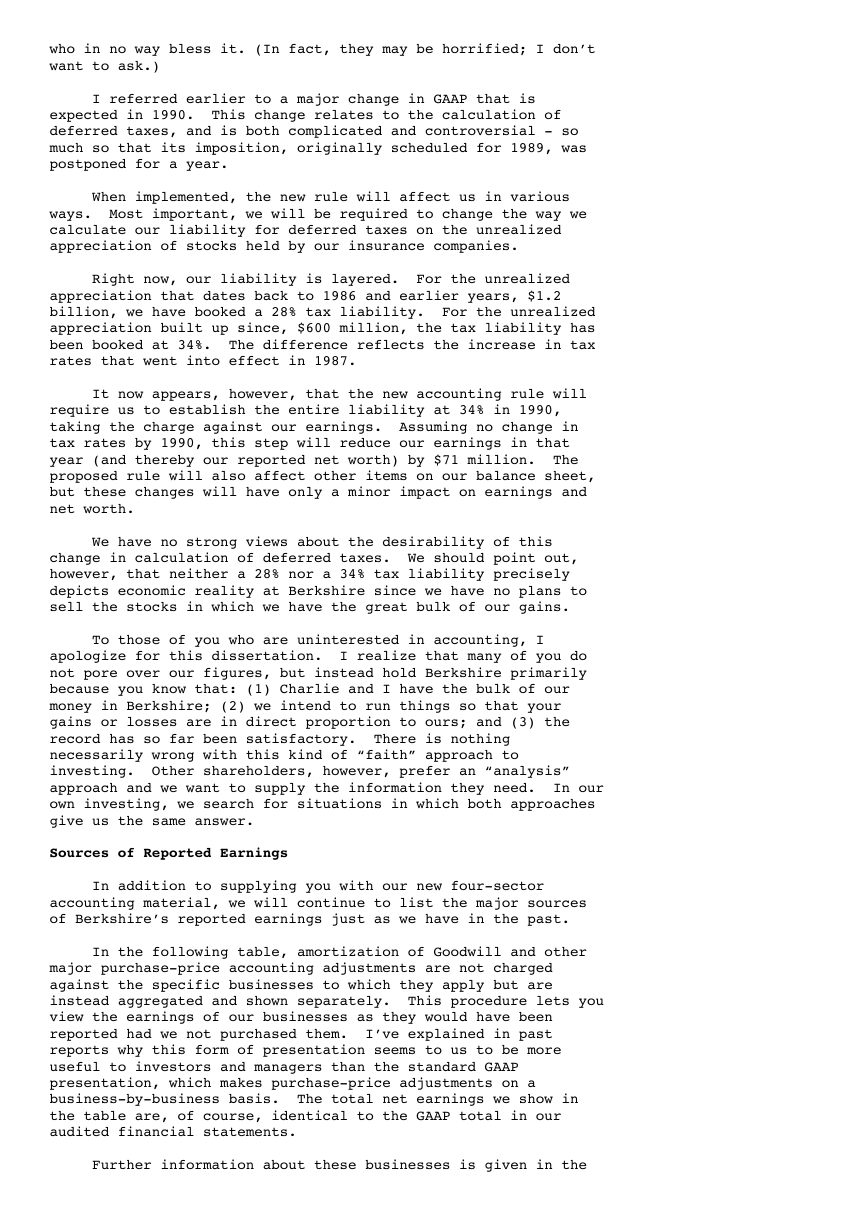

In the following table, amortization of Goodwill and other

major purchase-price accounting adjustments are not charged

against the specific businesses to which they apply but are

instead aggregated and shown separately. This procedure lets you

view the earnings of our businesses as they would have been

reported had we not purchased them. I’ve explained in past

reports why this form of presentation seems to us to be more

useful to investors and managers than the standard GAAP

presentation, which makes purchase-price adjustments on a

business-by-business basis. The total net earnings we show in

the table are, of course, identical to the GAAP total in our

audited financial statements.

Further information about these businesses is given in the

�

Business Segment section on pages 32-34, and in the Management’s

Discussion section on pages 36-40. In these sections you also

will find our segment earnings reported on a GAAP basis. For

information on Wesco’s businesses, I urge you to read Charlie

Munger’s letter, which starts on page 52. It contains the best

description I have seen of the events that produced the present

savings-and-loan crisis. Also, take special note of Dave

Hillstrom’s performance at Precision Steel Warehouse, a Wesco

subsidiary. Precision operates in an extremely competitive

industry, yet Dave consistently achieves good returns on invested

capital. Though data is lacking to prove the point, I think it

is likely that his performance, both in 1988 and years past,

would rank him number one among his peers.

(000s omitted)

------------------------------------------

Berkshire's Share

of Net Earnings

(after taxes and

Pre-Tax Earnings minority interests)

------------------- -------------------

1988 1987 1988 1987

-------- -------- -------- --------

Operating Earnings:

Insurance Group:

Underwriting ............... $(11,081) $(55,429) $ (1,045) $(20,696)

Net Investment Income ...... 231,250 152,483 197,779 136,658

Buffalo News ................. 42,429 39,410 25,462 21,304

Fechheimer ................... 14,152 13,332 7,720 6,580

Kirby ........................ 26,891 22,408 17,842 12,891

Nebraska Furniture Mart ...... 18,439 16,837 9,099 7,554

Scott Fetzer

Manufacturing Group ....... 28,542 30,591 17,640 17,555

See’s Candies ................ 32,473 31,693 19,671 17,363

Wesco - other than Insurance 16,133 6,209 10,650 4,978

World Book ................... 27,890 25,745 18,021 15,136

Amortization of Goodwill ..... (2,806) (2,862) (2,806) (2,862)

Other Purchase-Price

Accounting Charges ........ (6,342) (5,546) (7,340) (6,544)

Interest on Debt* ............ (35,613) (11,474) (23,212) (5,905)

Shareholder-Designated

Contributions ............. (4,966) (4,938) (3,217) (2,963)

Other ........................ 41,059 23,217 27,177 13,697

-------- -------- -------- --------

Operating Earnings ............. 418,450 281,676 313,441 214,746

Sales of Securities ............ 131,671 28,838 85,829 19,806

-------- -------- -------- --------

Total Earnings - All Entities .. $550,121 $310,514 $399,270 $234,552

*Excludes interest expense of Scott Fetzer Financial Group.

The earnings achieved by our operating businesses are

superb, whether measured on an absolute basis or against those of

their competitors. For that we thank our operating managers: You

and I are fortunate to be associated with them.

At Berkshire, associations like these last a long time. We

do not remove superstars from our lineup merely because they have

attained a specified age - whether the traditional 65, or the 95

reached by Mrs. B on the eve of Hanukkah in 1988. Superb

managers are too scarce a resource to be discarded simply because

a cake gets crowded with candles. Moreover, our experience with

newly-minted MBAs has not been that great. Their academic

records always look terrific and the candidates always know just

what to say; but too often they are short on personal commitment

to the company and general business savvy. It’s difficult to

teach a new dog old tricks.

Here’s an update on our major non-insurance operations:

�

o At Nebraska Furniture Mart, Mrs. B (Rose Blumkin) and her

cart roll on and on. She’s been the boss for 51 years, having

started the business at 44 with $500. (Think what she would have

done with $1,000!) With Mrs. B, old age will always be ten years

away.

The Mart, long the largest home furnishings store in the

country, continues to grow. In the fall, the store opened a

detached 20,000 square foot Clearance Center, which expands our

ability to offer bargains in all price ranges.

Recently Dillard’s, one of the most successful department

store operations in the country, entered the Omaha market. In

many of its stores, Dillard’s runs a full furniture department,

undoubtedly doing well in this line. Shortly before opening in

Omaha, however, William Dillard, chairman of the company,

announced that his new store would not sell furniture. Said he,

referring to NFM: “We don’t want to compete with them. We think

they are about the best there is.”

At the Buffalo News we extol the value of advertising, and

our policies at NFM prove that we practice what we preach. Over

the past three years NFM has been the largest ROP advertiser in

the Omaha World-Herald. (ROP advertising is the kind printed in

the paper, as contrasted to the preprinted-insert kind.) In no

other major market, to my knowledge, is a home furnishings

operation the leading customer of the newspaper. At times, we

also run large ads in papers as far away as Des Moines, Sioux

City and Kansas City - always with good results. It truly does

pay to advertise, as long as you have something worthwhile to

offer.

Mrs. B’s son, Louie, and his boys, Ron and Irv, complete the

winning Blumkin team. It’s a joy to work with this family. All

its members have character that matches their extraordinary

abilities.

o Last year I stated unequivocally that pre-tax margins at

The Buffalo News would fall in 1988. That forecast would have

proved correct at almost any other newspaper our size or larger.

But Stan Lipsey - bless him - has managed to make me look

foolish.

Though we increased our prices a bit less than the industry

average last year, and though our newsprint costs and wage rates

rose in line with industry norms, Stan actually improved margins

a tad. No one in the newspaper business has a better managerial

record. He has achieved it, furthermore, while running a paper

that gives readers an extraordinary amount of news. We believe

that our “newshole” percentage - the portion of the paper devoted

to news - is bigger than that of any other dominant paper of our

size or larger. The percentage was 49.5% in 1988 versus 49.8% in

1987. We are committed to keeping it around 50%, whatever the

level or trend of profit margins.

Charlie and I have loved the newspaper business since we

were youngsters, and we have had great fun with the News in the

12 years since we purchased it. We were fortunate to find Murray

Light, a top-flight editor, on the scene when we arrived and he

has made us proud of the paper ever since.

o See’s Candies sold a record 25.1 million pounds in 1988.

Prospects did not look good at the end of October, but excellent

Christmas volume, considerably better than the record set in

1987, turned the tide.

As we’ve told you before, See’s business continues to become

more Christmas-concentrated. In 1988, the Company earned a

�

record 90% of its full-year profits in December: $29 million out

of $32.5 million before tax. (It’s enough to make you believe in

Santa Claus.) December’s deluge of business produces a modest

seasonal bulge in Berkshire’s corporate earnings. Another small

bulge occurs in the first quarter, when most World Book annuals

are sold.

Charlie and I put Chuck Huggins in charge of See’s about

five minutes after we bought the company. Upon reviewing his

record, you may wonder what took us so long.

o At Fechheimer, the Heldmans - Bob, George, Gary, Roger and

Fred - are the Cincinnati counterparts of the Blumkins. Neither

furniture retailing nor uniform manufacturing has inherently

attractive economics. In these businesses, only exceptional

managements can deliver high returns on invested capital. And

that’s exactly what the five Heldmans do. (As Mets announcer

Ralph Kiner once said when comparing pitcher Steve Trout to his

father, Dizzy Trout, the famous Detroit Tigers pitcher: “There’s

a lot of heredity in that family.”)

Fechheimer made a fairly good-sized acquisition in 1988.

Charlie and I have such confidence in the business savvy of the

Heldman family that we okayed the deal without even looking at

it. There are very few managements anywhere - including those

running the top tier companies of the Fortune 500 - in which we

would exhibit similar confidence.

Because of both this acquisition and some internal growth,

sales at Fechheimer should be up significantly in 1989.

o All of the operations managed by Ralph Schey - World Book,

Kirby, and The Scott Fetzer Manufacturing Group - performed

splendidly in 1988. Returns on the capital entrusted to Ralph

continue to be exceptional.

Within the Scott Fetzer Manufacturing Group, particularly

fine progress was recorded at its largest unit, Campbell

Hausfeld. This company, the country’s leading producer of small

and medium-sized air compressors, has more than doubled earnings

since 1986.

Unit sales at both Kirby and World Book were up

significantly in 1988, with export business particularly strong.

World Book became available in the Soviet Union in September,

when that country’s largest American book store opened in Moscow.

Ours is the only general encyclopedia offered at the store.

Ralph’s personal productivity is amazing: In addition to

running 19 businesses in superb fashion, he is active at The

Cleveland Clinic, Ohio University, Case Western Reserve, and a

venture capital operation that has spawned sixteen Ohio-based

companies and resurrected many others. Both Ohio and Berkshire

are fortunate to have Ralph on their side.

Borsheim’s

It was in 1983 that Berkshire purchased an 80% interest in

The Nebraska Furniture Mart. Your Chairman blundered then by

neglecting to ask Mrs. B a question any schoolboy would have

thought of: “Are there any more at home like you?” Last month I

corrected the error: We are now 80% partners with another branch

of the family.

After Mrs. B came over from Russia in 1917, her parents and

five siblings followed. (Her two other siblings had preceded

her.) Among the sisters was Rebecca Friedman who, with her

husband, Louis, escaped in 1922 to the west through Latvia in a

journey as perilous as Mrs. B’s earlier odyssey to the east

�

through Manchuria. When the family members reunited in Omaha

they had no tangible assets. However, they came equipped with an

extraordinary combination of brains, integrity, and enthusiasm

for work - and that’s all they needed. They have since proved

themselves invincible.

In 1948 Mr. Friedman purchased Borsheim’s, a small Omaha

jewelry store. He was joined in the business by his son, Ike, in

1950 and, as the years went by, Ike’s son, Alan, and his sons-in-

law, Marvin Cohn and Donald Yale, came in also.

You won’t be surprised to learn that this family brings to

the jewelry business precisely the same approach that the

Blumkins bring to the furniture business. The cornerstone for

both enterprises is Mrs. B’s creed: “Sell cheap and tell the

truth.” Other fundamentals at both businesses are: (1) single

store operations featuring huge inventories that provide

customers with an enormous selection across all price ranges, (2)

daily attention to detail by top management, (3) rapid turnover,

(4) shrewd buying, and (5) incredibly low expenses. The

combination of the last three factors lets both stores offer

everyday prices that no one in the country comes close to

matching.

Most people, no matter how sophisticated they are in other

matters, feel like babes in the woods when purchasing jewelry.

They can judge neither quality nor price. For them only one rule

makes sense: If you don’t know jewelry, know the jeweler.

I can assure you that those who put their trust in Ike

Friedman and his family will never be disappointed. The way in

which we purchased our interest in their business is the ultimate

testimonial. Borsheim’s had no audited financial statements;

nevertheless, we didn’t take inventory, verify receivables or

audit the operation in any way. Ike simply told us what was so -

- and on that basis we drew up a one-page contract and wrote a

large check.

Business at Borsheim’s has mushroomed in recent years as the

reputation of the Friedman family has spread. Customers now come

to the store from all over the country. Among them have been

some friends of mine from both coasts who thanked me later for

getting them there.

Borsheim’s new links to Berkshire will change nothing in the

way this business is run. All members of the Friedman family

will continue to operate just as they have before; Charlie and I

will stay on the sidelines where we belong. And when we say “all

members,” the words have real meaning. Mr. and Mrs. Friedman, at

88 and 87, respectively, are in the store daily. The wives of

Ike, Alan, Marvin and Donald all pitch in at busy times, and a

fourth generation is beginning to learn the ropes.

It is great fun to be in business with people you have long

admired. The Friedmans, like the Blumkins, have achieved success

because they have deserved success. Both families focus on

what’s right for the customer and that, inevitably, works out

well for them, also. We couldn’t have better partners.

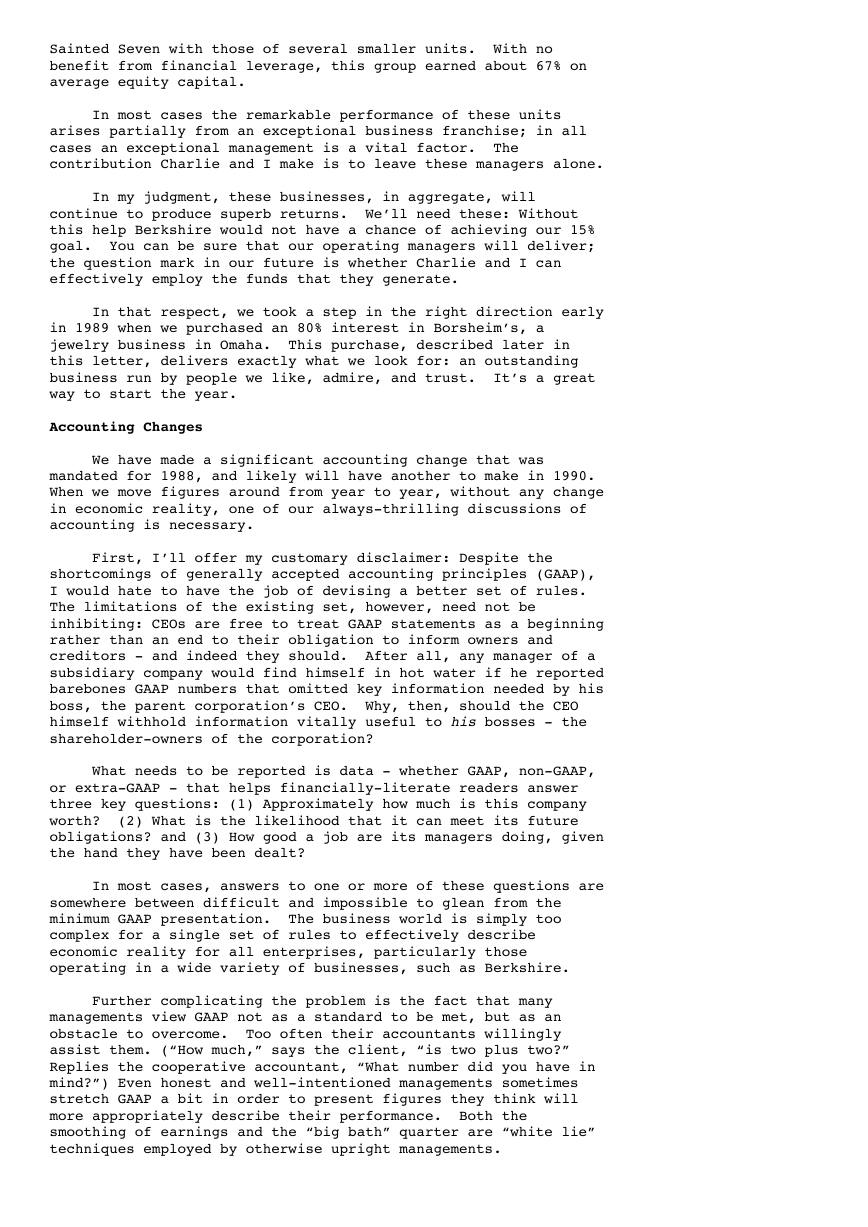

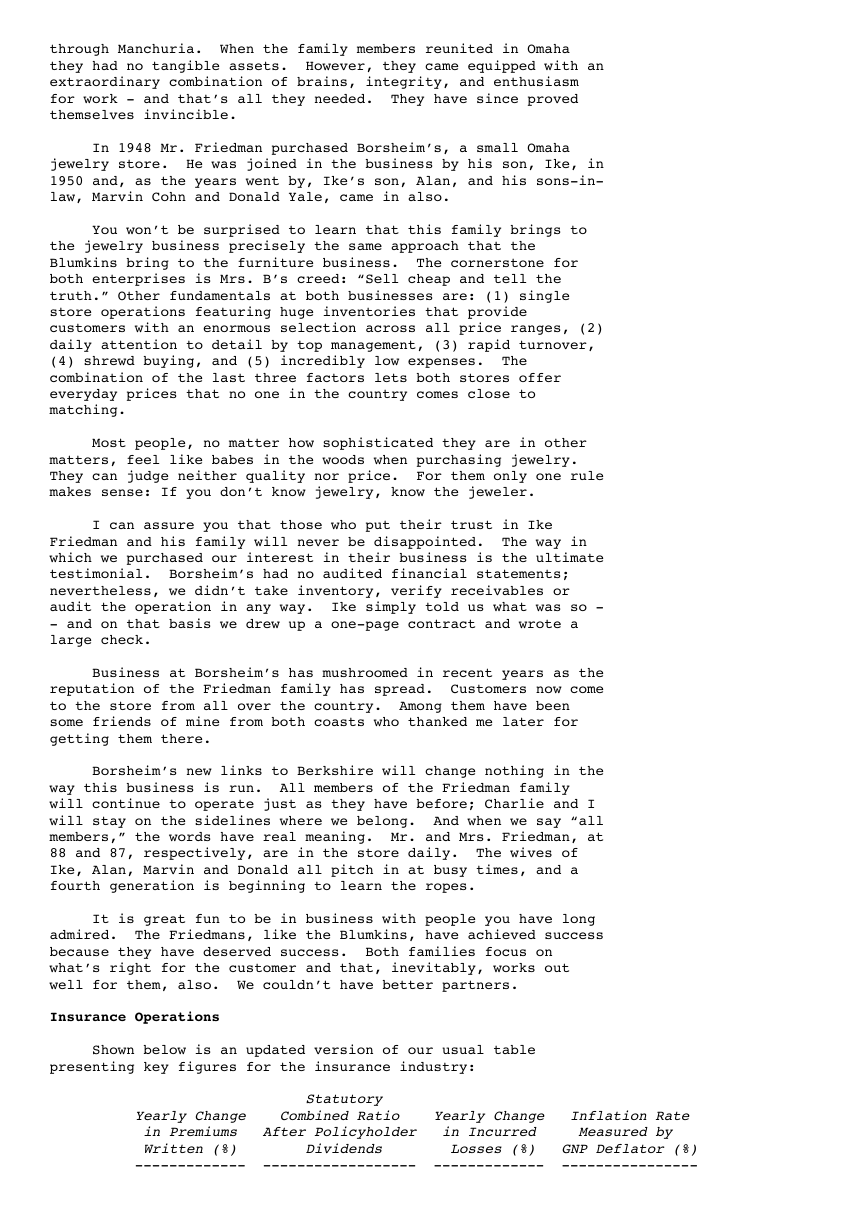

Insurance Operations

Shown below is an updated version of our usual table

presenting key figures for the insurance industry:

Statutory

Yearly Change Combined Ratio Yearly Change Inflation Rate

in Premiums After Policyholder in Incurred Measured by

Written (%) Dividends Losses (%) GNP Deflator (%)

------------- ------------------ ------------- ----------------

�