8

1

0

2

y

a

M

4

2

]

R

I

.

s

c

[

2

v

9

4

3

2

0

.

3

0

8

1

:

v

i

X

r

a

Billion-scale Commodity Embedding for E-commerce

Recommendation in Alibaba

Jizhe Wang, Pipei Huang∗

Alibaba Group

Hangzhou and Beijing, China

{jizhe.wjz,pipei.hpp}@alibaba-inc.com

{jizhe.wjz,pipei.hpp}@gmail.com

Zhibo Zhang, Binqiang Zhao

Alibaba Group

Beijing, China

{shaobo.zzb,binqiang.zhao}@alibaba-inc.com

Huan Zhao

Department of Computer Science and Engineering

Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

Kowloon, Hong Kong

hzhaoaf@cse.ust.hk

Dik Lun Lee

Kowloon, Hong Kong

dlee@cse.ust.hk

Department of Computer Science and Engineering

Hong Kong University of Science and Technology

ABSTRACT

Recommender systems (RSs) have been the most important

technology for increasing the business in Taobao, the largest online

consumer-to-consumer (C2C) platform in China. There are three

major challenges facing RS in Taobao: scalability, sparsity and

cold start. In this paper, we present our technical solutions to

address these three challenges. The methods are based on a well-

known graph embedding framework. We first construct an item

graph from users’ behavior history, and learn the embeddings of all

items in the graph. The item embeddings are employed to compute

pairwise similarities between all items, which are then used in

the recommendation process. To alleviate the sparsity and cold

start problems, side information is incorporated into the graph

embedding framework. We propose two aggregation methods to

integrate the embeddings of items and the corresponding side

information. Experimental results from offline experiments show

that methods incorporating side information are superior to those

that do not. Further, we describe the platform upon which the

embedding methods are deployed and the workflow to process

the billion-scale data in Taobao. Using A/B test, we show that the

online Click-Through-Rates (CTRs) are improved comparing to

the previous collaborative filtering based methods widely used in

Taobao, further demonstrating the effectiveness and feasibility of

our proposed methods in Taobao’s live production environment.

CCS CONCEPTS

• Information systems → Collaborative filtering; Recom-

mender systems; • Mathematics of computing → Graph

∗Pipei Huang is the Corresponding author.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or

classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation

on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than ACM

must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or republish,

to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a

fee. Request permissions from permissions@acm.org.

KDD ’18, August 19–23, 2018, London, United Kingdom

© 2018 Association for Computing Machinery.

ACM ISBN 978-1-4503-5552-0/18/08...$15.00

https://doi.org/10.1145/3219819.3219869

algorithms; • Computing methodologies → Learning latent

representations;

KEYWORDS

Recommendation system; Collaborative filtering;

Graph Embedding; E-commerce Recommendation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Internet technology has been continuously reshaping the business

landscape, and online businesses are everywhere nowadays.

Alibaba, the largest provider of online business in China, makes it

possible for people or companies all over the world to do business

online. With one billion users, the Gross Merchandise Volume

(GMV) of Alibaba in 2017 is 3,767 billion Yuan and the revenue

in 2017 is 158 billion Yuan. In the famous Double-Eleven Day, the

largest online shopping festival in China, in 2017, the total amount

of transactions was around 168 billion Yuan. Among all kinds of

online platforms in Alibaba, Taobao1, the largest online consumer-

to-consumer (C2C) platform, stands out by contributing 75% of the

total traffic in Alibaba E-commerce.

With one billion users and two billion items, i.e., commodities,

in Taobao, the most critical problem is how to help users find

the needed and interesting items quickly. To achieve this goal,

recommendation, which aims at providing users with interesting

items based on their preferences, becomes the key technology in

Taobao. For example, the homepage on Mobile Taobao App (see

Figure 1), which are generated based on users’ past behaviors

with recommendation techniques, contributes 40% of the total

recommending traffic. Furthermore, recommendation contributes

the majority of both revenues and traffic in Taobao. In short, rec-

ommendation has become the vital engine of GMV and revenues of

Taobao and Alibaba. Despite the success of various recommendation

methods in academia and industry, e.g., collaborative filtering

(CF) [9, 11, 16], content-based methods [2], and deep learning based

methods [5, 6, 22], the problems facing these methods become more

severe in Taobao because of the billion-scale of users and items.

There are three major technical challenges facing RS in Taobao:

1https://www.taobao.com/

�

Figure 1: The areas highlighted with dashed rectangles are personalized for one billion users in Taobao. Attractive images

and textual descriptions are also generated for better user experience. Note they are on Mobile Taobao App homepage, which

contributes 40% of the total recommending traffic.

• Scalability: Despite the fact that many existing recommen-

dation approaches work well on smaller scale datasets, i.e.,

millions of users and items, they fail on the much larger

scale dataset in Taobao, i.e., one billion users and two billion

items.

• Sparsity: Due to the fact that users tend to interact with

only a small number of items, it is extremely difficult to train

an accurate recommending model, especially for users or

items with quite a small number of interactions. It is usually

referred to as the “sparsity” problem.

• Cold Start: In Taobao, millions of new items are contin-

uously uploaded each hour. There are no user behaviors

for these items. It is challenging to process these items or

predict the preferences of users for these items, which is the

so-called “cold start” problem.

To address these challenges in Taobao, we design a two-stage

recommending framework in Taobao’s technology platform. The

first stage is matching, and the second is ranking. In the matching

stage, we generate a candidate set of similar items for each item

users have interacted with, and then in the ranking stage, we train

a deep neural net model, which ranks the candidate items for each

user according to his or her preferences. Due to the aforementioned

challenges, in both stages we have to face different unique problems.

Besides, the goal of each stage is different, leading to separate

technical solutions.

In this paper, we focus on how to address the challenges in

the matching stage, where the core task is the computation of

pairwise similarities between all items based on users’ behaviors.

After the pairwise similarities of items are obtained, we can generate

a candidate set of items for further personalization in the ranking

stage. To achieve this, we propose to construct an item graph

from users’ behavior history and then apply the state-of-art graph

embedding methods [8, 15, 17] to learn the embedding of each item,

dubbed Base Graph Embedding (BGE). In this way, we can generate

the candidate set of items based on the similarities computed

from the dot product of the embedding vectors of items. Note

that in previous works, CF based methods are used to compute

these similarities. However, CF based methods only consider the

co-occurrence of items in users’ behavior history [9, 11, 16].

In our work, using random walk in the item graph, we can

capture higher-order similarities between items. Thus, it is superior

to CF based methods. However, it’s still a challenge to learn

accurate embeddings of items with few or even no interactions.

To alleviate this problem, we propose to use side information to

enhance the embedding procedure, dubbed Graph Embedding with

Side information (GES). For example, items belong to the same

category or brand should be closer in the embedding space. In

this way, we can obtain accurate embeddings of items with few

or even no interactions. However, in Taobao, there are hundreds

of types of side information, like category, brand, or price, etc.,

and it is intuitive that different side information should contribute

differently to learning the embeddings of items. Thus, we further

propose a weighting mechanism when learning the embedding

with side information, dubbed Enhanced Graph Embedding with

Side information (EGES).

In summary, there are three important parts in the matching

stage:

(1) Based on years of practical experience in Taobao, we design

an effective heuristic method to construct the item graph

from the behavior history of one billion users in Taobao.

(2) We propose three embedding methods, BGE, GES, and EGES,

to learn embeddings of two billion items in Taobao. We

conduct offline experiments to demonstrate the effectiveness

of GES and EGES comparing to BGE and other embedding

methods.

(3) To deploy the proposed methods for billion-scale users and

items in Taobao, we build the graph embedding systems on

the XTensorflow (XTF) platform constructed by our team. We

�

show that the proposed framework significantly improves

recommending performance on the Mobile Taobao App,

while satisfying the demand of training efficiency and instant

response of service even on the Double-Eleven Day.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we

elaborate on the three proposed embedding methods. Offline and

online experimental results are presented in Section 3. We introduce

the deployment of the system in Taobao in Section 4, and review

the related work in Section 5. We conclude our work in Section 6.

2 FRAMEWORK

In this section, we first introduce the basics of graph embedding,

and then elaborate on how we construct the item graph from users’

behavior history. Finally, we study the proposed methods to learn

the embeddings of items in Taobao.

2.1 Preliminaries

In this section, we give an overview of graph embedding and one of

the most popular methods, DeepWalk [15], based on which we

propose our graph embedding methods in the matching stage.

Given a graph G = (V, E), where V and E represent the node

set and the edge set, respectively. Graph embedding is to learn a

low-dimensional representation for each node v ∈ V in the space

Rd, where d ≪ |V|. In other words, our goal is to learn a mapping

function Φ : V → Rd, i.e., representing each node in V as a

d-dimensional vector.

In [13, 14], word2vec was proposed to learn the embedding of

each word in a corpus. Inspired by word2vec, Perozzi et al. proposed

DeepWalk to learn the embedding of each node in a graph [15].

They first generate sequences of nodes by running random walk

in the graph, and then apply the Skip-Gram algorithm to learn

the representation of each node in the graph. To preserve the

topological structure of the graph, they need to solve the following

optimization problem:

minimize

− log Pr(c|Φ(v)) ,

�

�

(1)

Φ

v ∈V

c∈N(v)

where N(v) is the neighborhood of node v, which can be defined

as nodes within one or two hops from v. Pr(c|Φ(v)) defines the

conditional probability of having a context node c given a node v.

In the rest of this section, we first present how we construct

the item graph from users’ behaviors, and then propose the

graph embedding methods based on DeepWalk for generating low-

dimensional representation for two billion items in Taobao.

2.2 Construction of Item Graph from Users’

Behaviors

In this section, we elaborate on the construction of the item graph

from users’ behaviors. In reality, a user’s behaviors in Taobao tend

to be sequential as shown in Figure 2 (a). Previous CF based methods

only consider the co-occurrence of items, but ignore the sequential

information, which can reflect users’ preferences more precisely.

However, it is not possible to use the whole history of a user because

1) the computational and space cost will be too expensive with so

many entries; 2) a user’s interests tend to drift with time. Therefore,

in practice, we set a time window and only choose users’ behaviors

within the window. This is called session-based users’ behaviors.

Empirically, the duration of the time window is one hour.

After we obtain the session-based users’ behaviors, two items

are connected by a directed edge if they occur consecutively, e.g.,

in Figure 2 (b) item D and item A are connected because user u1

accessed item D and A consecutively as shown in Figure 2 (a).

By utilizing the collaborative behaviors of all users in Taobao, we

assign a weight to each edge eij based on the total number of

occurrences of the two connected items in all users’ behaviors.

Specifically, the weight of the edge is equal to the frequency of

item i transiting to item j in the whole users’ behavior history. In

this way, the constructed item graph can represent the similarity

between different items based on all of the users’ behaviors in

Taobao.

In practice, before we extract users’ behavior sequences, we need

to filter out invalid data and abnormal behaviors to eliminate noise

for our proposed methods. Currently, the following behaviors are

regarded as noise in our system:

the click may be unintentional and needs to be removed.

• If the duration of the stay after a click is less than one second,

• There are some “over-active” users in Taobao, who are ac-

tually spam users. According to our long-term observations

in Taobao, if a single user bought 1,000 items or his/her

total number of clicks is larger than 3,500 in less than three

months, it is very likely that the user is a spam user. We need

to filter out the behaviors of these users.

• Retailers in Taobao keep updating the details of a commodity.

In the extreme case, a commodity can become a totally

different item for the same identifier in Taobao after a long

sequence of updates. Thus, we remove the item related to

the identifier.

2.3 Base Graph Embedding

After we obtain the weighted directed item graph, denoted as G =

(V, E), we adopt DeepWalk to learn the embedding of each node

in G. Let M denote the adjacency matrix of G and Mij the weight

of the edge from node i pointing to node j. We first generate node

sequences based on random walk and then run the Skip-Gram

algorithm on the sequences. The transition probability of random

walk is defined as

Mi j�

j∈N+(vi )

0 ,

P(vj|vi) =

, vj ∈ N+(vi) ,

Mi j

eij E ,

(2)

where N+(vi) represents the set of outlink neighbors, i.e. there are

edges from vi pointing to all of the nodes in N+(vi). By running

random walk, we can generate a number of sequences as shown in

Figure 2 (c).

Then we apply the Skip-Gram algorithm [13, 14] to learn the

embeddings, which maximizes the co-occurrence probability of

two nodes in the obtained sequences. This leads to the following

optimization problem:

− log Pr{vi−w , · · · , vi +w}\vi|Φ(vi) ,

(3)

minimize

Φ

�

(a) Users’ behavior sequences.

(b) Item graph construction.

(c) Random walk generation.

(d) Embedding with Skip-Gram.

Figure 2: Overview of graph embedding in Taobao: (a) Users’ behavior sequences: One session for user u1, two sessions for

user u2 and u3; these sequences are used to construct the item graph; (b) The weighted directed item graph G = (V, E); (c) The

sequences generated by random walk in the item graph; (d) Embedding with Skip-Gram.

where w is the window size of the context nodes in the sequences.

Using the independence assumption, we have

Pr{vi−w , · · · , vi +w}\vi|Φ(vi) =

log σΦ(vj)T Φ(vi) + �

into

minimize

Φ

t ∈N(vi)′

j=i−w, ji

i +w�

Prvj|Φ(vi) .

log σ − Φ(vt)T Φ(vi) .

(4)

Applying negative sampling [13, 14], Eq. (3) can be transformed

(5)

where N(vi)′ is the negative samples for vi, and σ() is the sigmoid

1+e−x . Empirically, the larger |N(vi)′| is, the better

function σ(x) =

1

the obtained results.

2.4 Graph Embedding with Side Information

By applying the embedding method in Section 2.3, we can

learn embeddings of all items in Taobao to capture higher-order

similarities in users’ behavior sequences, which are ignored by

previous CF based methods. However, it is still challenging to

learn accurate embeddings for “cold-start” items, i.e., those with no

interactions of users.

To address the cold-start problem, we propose to enhance BGE

using side information attached to cold-start items. In the context

of RSs in e-commerce, side information refers to the category, shop,

price, etc., of an item, which are widely used as key features in

the ranking stage but rarely applied in the matching stage. We can

alleviate the cold-start problem by incorporating side information

in graph embedding. For example, two hoodies (same category)

from UNIQLO (same shop) may look alike, and a person who likes

Nikon lens may also has an interest in Canon Camera (similar

category and similar brand). It means that items with similar side

information should be closer in the embedding space. Based on this

assumption, we propose the GES method as illustrated in Figure 3.

For the sake of clarity, we modify slightly the notations. We use

W to denote the embedding matrix of items or side information.

Specifically, W0

v denotes

the embedding of the s-th type of side information attached to

item v. Then, for item v with n types of side information, we have

v denotes the embedding of item v, and Ws

v ∈ Rd, where d is the embedding

n + 1 vectors W0

dimension. Note that the dimensions of the embeddings of items

and side information are empirically set to the same value.

v , · · · , ...Wn

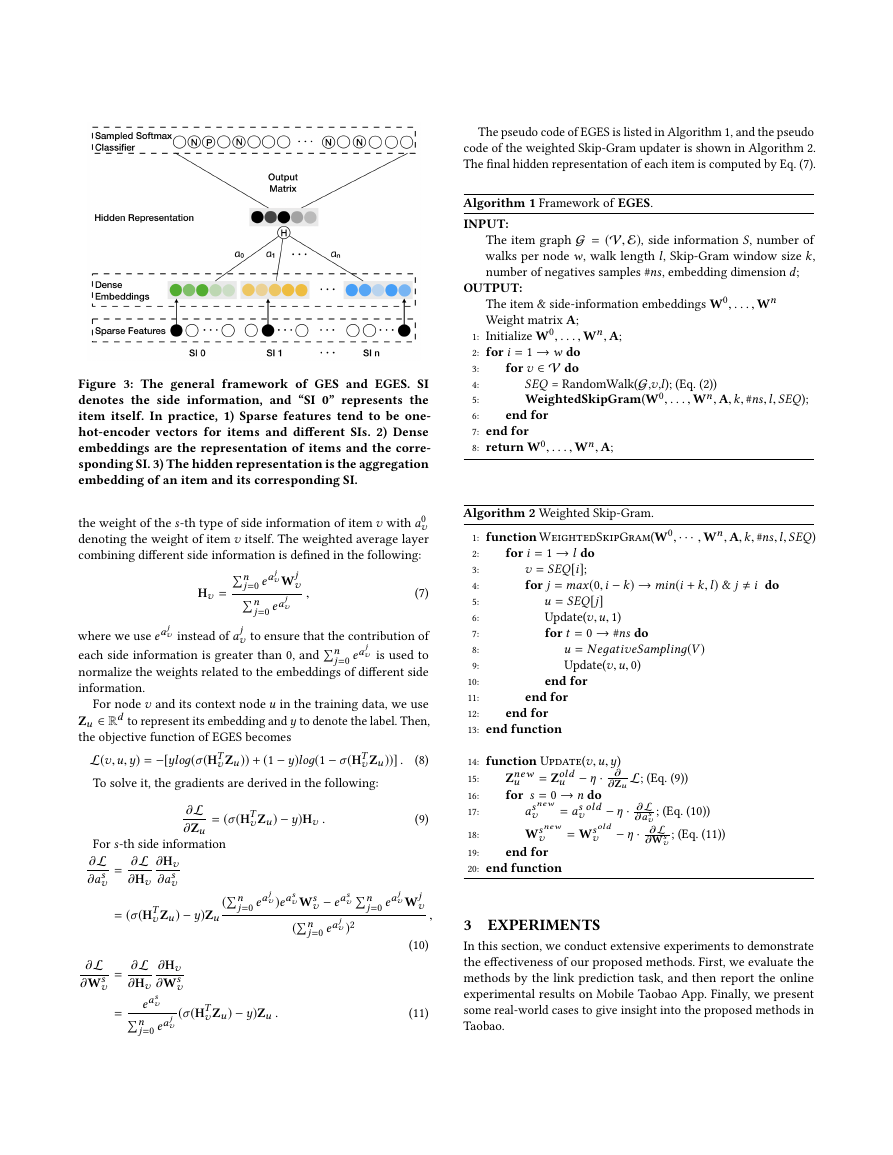

As shown in Figure 3, to incorporate side information, we

concatenate the n + 1 embedding vectors for item v and add a layer

with average-pooling operation to aggregate all of the embeddings

related to item v, which is

n�

s =0

Hv =

1

n + 1

Ws

v ,

(6)

where Hv is the aggregated embeddings of item v. In this way, we

incorporate side information in such a way that items with similar

side information will be closer in the embedding space. This results

in more accurate embeddings of cold-start items and improves the

offline and online performance (see Section 3).

2.5 Enhanced Graph Embedding with Side

Information

Despite the performance gain of GES, a problem remains when

integrating different kinds of side information in the embedding

procedure. In Eq. (6), the assumption is that different kinds of side

information contribute equally to the final embedding, which does

not reflect the reality. For example, a user who has bought an iPhone

tends to view Macbook or iPad because of the brand “Apple”, while

a user may buy clothes of different brands in the same shop in

Taobao for convenience and lower price. Therefore, different kinds

of side information contribute differently to the co-occurrence of

items in users’ behaviors.

To address this problem, we propose the EGES method to

aggregate different types of side information. The framework is the

same to GES (see Figure 3). The idea is that different types of side

information have different contributions when their embeddings

are aggregated. Hence, we propose a weighted average layer to

aggregate the embeddings of the side information related to the

items. Given an item v, let A ∈ R|V |×(n+1) be the weight matrix

and the entry Aij the weight of the j-th type of side information

of the i-th item. Note that A∗0, i.e., the first column of A, denotes

the weight of item v itself. For simplicity, we use as

v to denote

�

The pseudo code of EGES is listed in Algorithm 1, and the pseudo

code of the weighted Skip-Gram updater is shown in Algorithm 2.

The final hidden representation of each item is computed by Eq. (7).

Algorithm 1 Framework of EGES.

INPUT:

OUTPUT:

The item graph G = (V, E), side information S, number of

walks per node w, walk length l, Skip-Gram window size k,

number of negatives samples #ns, embedding dimension d;

The item & side-information embeddings W0

Weight matrix A;

1: Initialize W0

2: for i = 1 → w do

for v ∈ V do

3:

4:

5:

end for

6:

7: end for

8: return W0

SEQ = RandomWalk(G,v,l); (Eq. (2))

WeightedSkipGram(W0

, . . . , Wn, A, k, #ns, l, SEQ);

, . . . , Wn, A;

, . . . , Wn, A;

, . . . , Wn

Figure 3: The general framework of GES and EGES. SI

denotes the side information, and “SI 0” represents the

item itself. In practice, 1) Sparse features tend to be one-

hot-encoder vectors for items and different SIs. 2) Dense

embeddings are the representation of items and the corre-

sponding SI. 3) The hidden representation is the aggregation

embedding of an item and its corresponding SI.

�n

�n

j =0 ea j

v Wj

v

j=0 ea j

v

0

the weight of the s-th type of side information of item v with a

v

denoting the weight of item v itself. The weighted average layer

combining different side information is defined in the following:

Hv =

,

(7)

v instead of a

where we use ea j

each side information is greater than 0, and�n

v to ensure that the contribution of

j

v is used to

normalize the weights related to the embeddings of different side

information.

For node v and its context node u in the training data, we use

Zu ∈ Rd to represent its embedding and y to denote the label. Then,

the objective function of EGES becomes

L(v, u, y) = −[yloд(σ(HT

v Zu)) + (1 − y)loд(1 − σ(HT

To solve it, the gradients are derived in the following:

v Zu))] .

j=0 ea j

(8)

∂L

∂Zu

= (σ(HT

v Zu) − y)Hv .

(9)

, · · · , Wn, A, k, #ns, l, SEQ)

for i = 1 → l do

v = SEQ[i];

for j = max(0, i − k) → min(i + k, l) & j i do

Algorithm 2 Weighted Skip-Gram.

1: function WeightedSkipGram(W0

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

11:

12:

13: end function

u = SEQ[j]

Update(v, u, 1)

for t = 0 → #ns do

u = N eдativeSamplinд(V)

Update(v, u, 0)

end for

end for

end for

L; (Eq. (9))

= Zold

Znew

u

for s = 0 → n do

14: function Update(v, u, y)

u − η · ∂

15:

∂Zu

16:

= as

17:

v

= Wsold

as new

v

Ws new

18:

19:

20: end function

v

end for

old − η · ∂L

∂as

v

− η · ∂L

∂Ws

v

v

; (Eq. (10))

; (Eq. (11))

For s-th side information

∂L

∂as

v

=

∂Hv

∂as

v

v Zu) − y)Zu

∂L

∂Hv

= (σ(HT

(�n

j=0 ea j

v )eas

j=0 ea j

v Wj

v

v�n

v Ws

(�n

v − eas

v )2

j=0 ea j

∂L

∂Ws

v

=

=

∂L

∂Hv

eas

j=0 ea j

v�n

∂Hv

∂Ws

v

(σ(HT

v

v Zu) − y)Zu .

,

3 EXPERIMENTS

In this section, we conduct extensive experiments to demonstrate

the effectiveness of our proposed methods. First, we evaluate the

methods by the link prediction task, and then report the online

experimental results on Mobile Taobao App. Finally, we present

some real-world cases to give insight into the proposed methods in

Taobao.

(10)

(11)

�

Table 1: Statistics of the two datasets. #SI denotes the number

of types of side information. Sparsity is computed according

to 1 −

#Edдes

#N odes×(#N odes−1).

#Nodes

Dataset

300,150

Amazon

Taobao

2,632,379

#Edges

3,740,196

44,997,887

#SI

3

12

Sparsity(%)

0.9958

0.9994

3.1 Offline Evaluation

Link Prediction. The link prediction task is used in the offline

experiments because it is a fundamental problem in networks. Given

a network with some edges removed, the link prediction task is

to predict the occurrence of links. Following similar experimental

settings in [30], 1/3 of the edges are randomly chosen and removed

as ground truth in the test set, and the remaining graph is taken as

the training set. The same number of node pairs in the test data with

no edges connecting them are randomly chosen as negative samples

in the test set. To evaluate the performance of link prediction,

the Area Under Curve (AUC) score is adopted as the performance

metric.

Dataset. We use two datasets for the link prediction task. The

first is Amazon Electronics2 provided by [12], denoted as Amazon.

The second is extracted from Mobile Taobao App, denoted as

Taobao. Both of these two datasets include different types of side

information. For the Amazon dataset, the item graph is constructed

from “co-purchasing” relations (denoted as also_bought in the

provided data), and three types of side information are used, i.e.,

category, sub-category and brand. For the Taobao dataset, the item

graph is constructed according to Section 2.2. Note that, for the sake

of efficiency and effectiveness, twelve types of side information are

used in Taobao’s live production, including retailer, brand, purchase

level, age, gender, style, etc. These types of side information have

been demonstrated to be useful according to years of practical

experience in Taobao. The statistics of the two datasets are shown

in Table 1. We can see that the sparsity of the two datasets are

greater than 99%.

Comparing Methods. Experiments are conducted to compare

four methods: BGE, LINE, GES, and EGES. LINE was proposed

in [17], which captures the first-order and second-order proximity

in graph embedding. We use the implementation provided by the

authors3, and run it using first-order and second-order proximity,

which are denoted, respectively, as LINE(1st) and LINE(2nd). We

implement the other three methods. The emdedding dimension

of all the methods is set to 160. For our BGE, GES and EGES, the

length of random walk is 10, the number of walks per node is 20,

and the context window is 5.

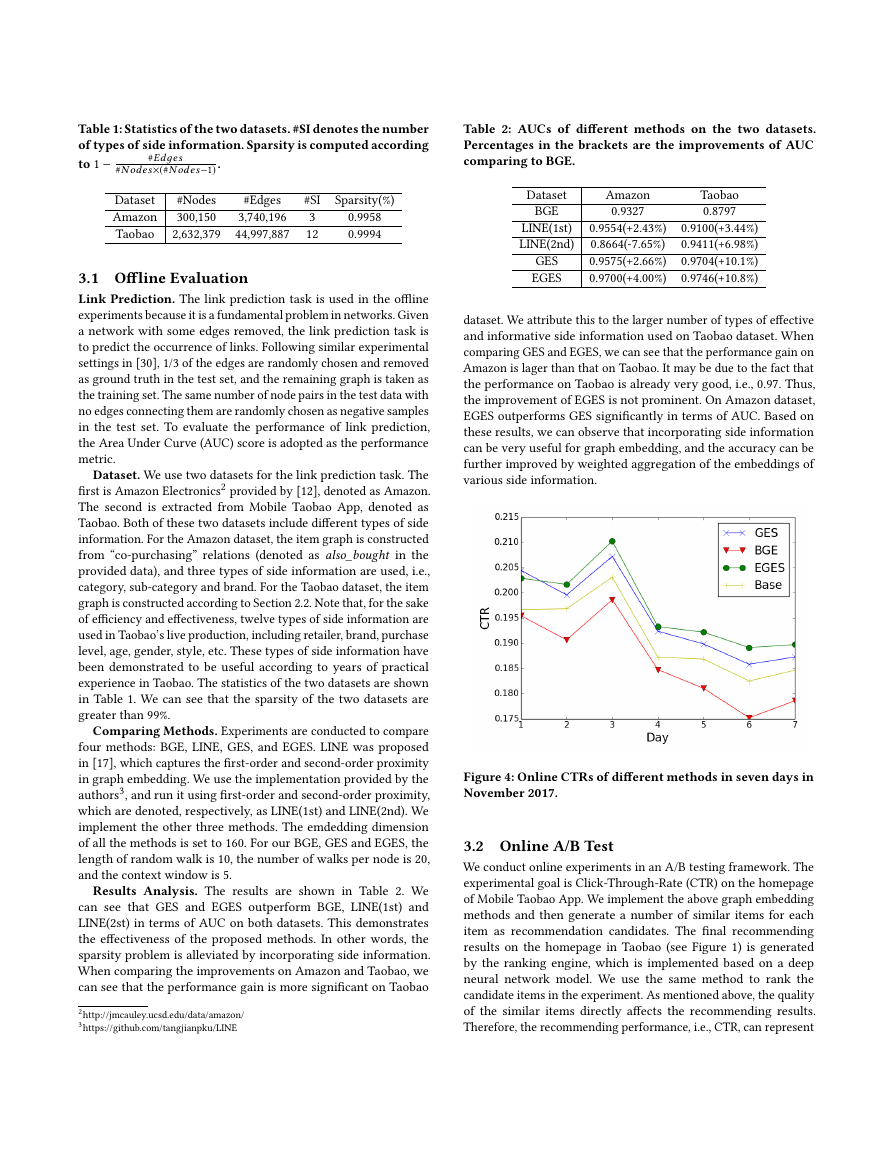

Results Analysis. The results are shown in Table 2. We

can see that GES and EGES outperform BGE, LINE(1st) and

LINE(2st) in terms of AUC on both datasets. This demonstrates

the effectiveness of the proposed methods. In other words, the

sparsity problem is alleviated by incorporating side information.

When comparing the improvements on Amazon and Taobao, we

can see that the performance gain is more significant on Taobao

2http://jmcauley.ucsd.edu/data/amazon/

3https://github.com/tangjianpku/LINE

Table 2: AUCs of different methods on the two datasets.

Percentages in the brackets are the improvements of AUC

comparing to BGE.

Dataset

BGE

LINE(1st)

LINE(2nd)

GES

EGES

Amazon

0.9327

0.9554(+2.43%)

0.8664(-7.65%)

0.9575(+2.66%)

0.9700(+4.00%)

Taobao

0.8797

0.9100(+3.44%)

0.9411(+6.98%)

0.9704(+10.1%)

0.9746(+10.8%)

dataset. We attribute this to the larger number of types of effective

and informative side information used on Taobao dataset. When

comparing GES and EGES, we can see that the performance gain on

Amazon is lager than that on Taobao. It may be due to the fact that

the performance on Taobao is already very good, i.e., 0.97. Thus,

the improvement of EGES is not prominent. On Amazon dataset,

EGES outperforms GES significantly in terms of AUC. Based on

these results, we can observe that incorporating side information

can be very useful for graph embedding, and the accuracy can be

further improved by weighted aggregation of the embeddings of

various side information.

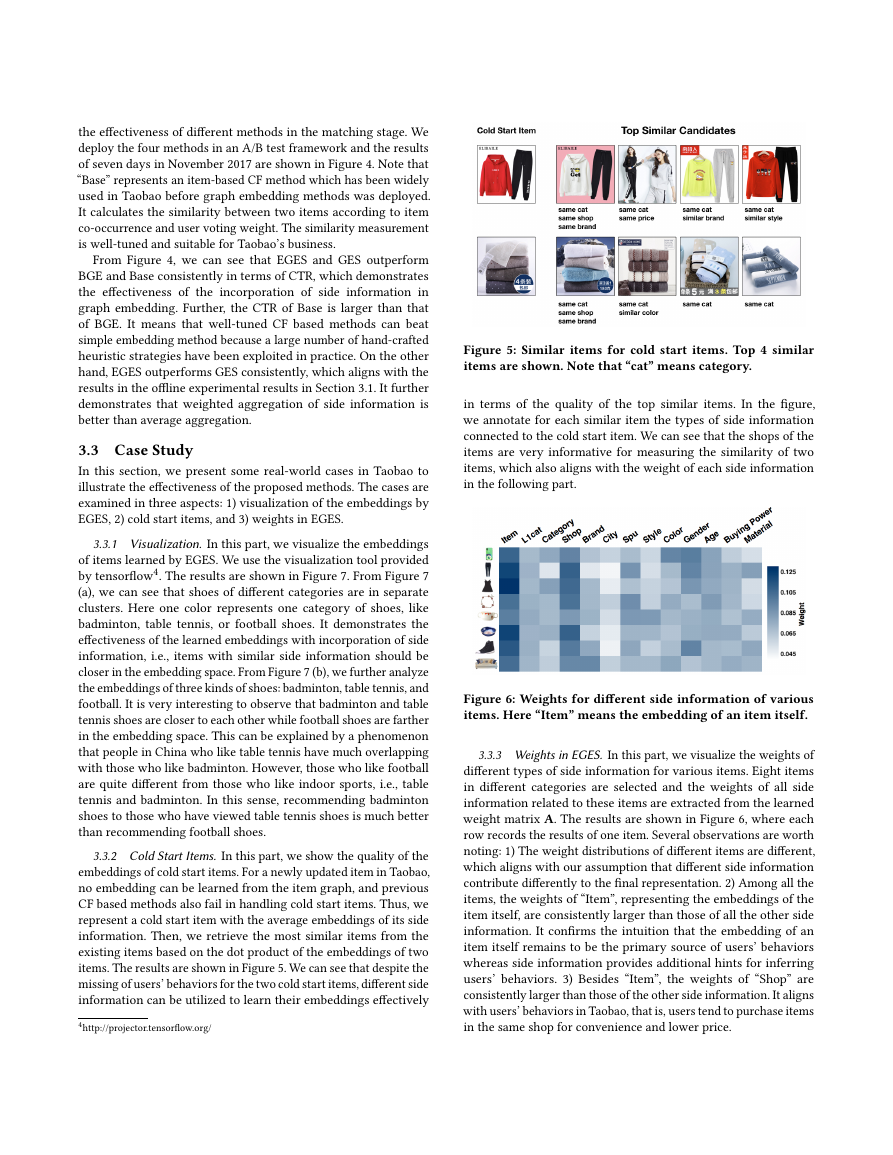

Figure 4: Online CTRs of different methods in seven days in

November 2017.

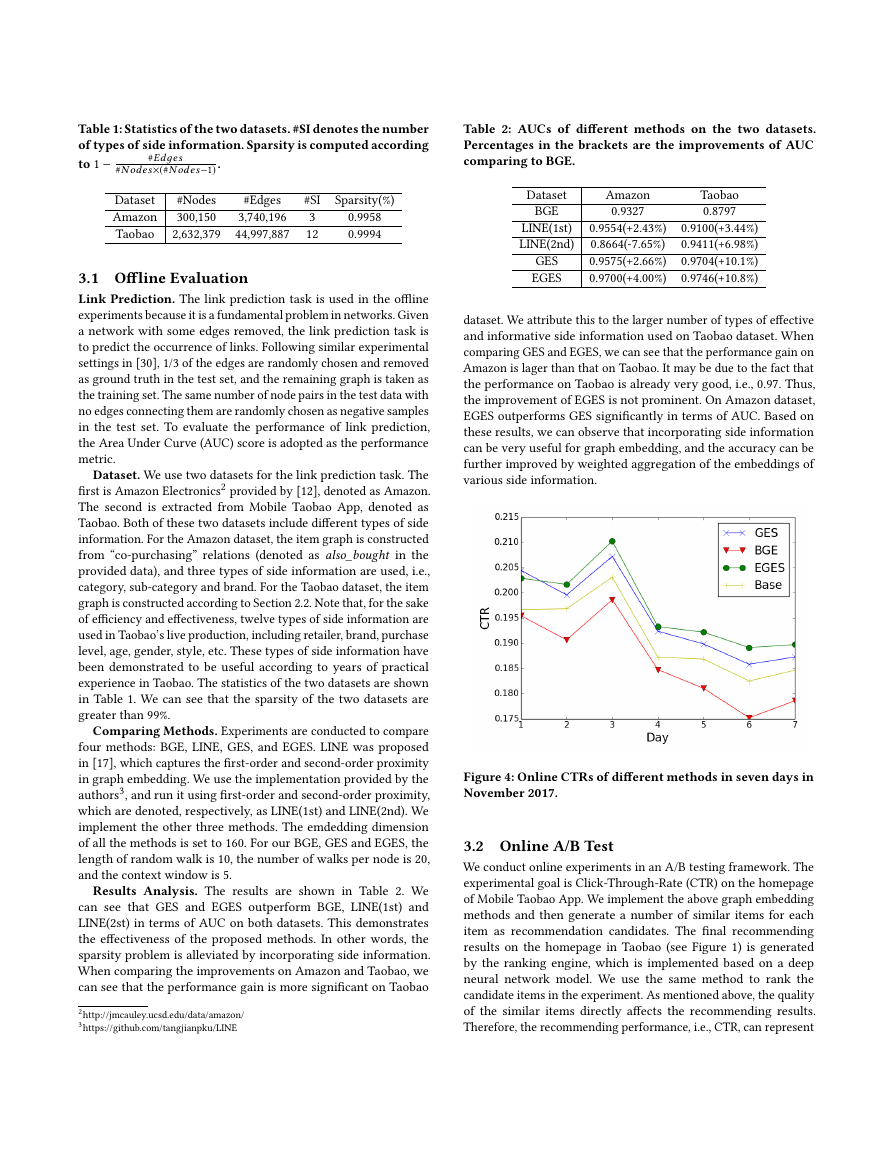

3.2 Online A/B Test

We conduct online experiments in an A/B testing framework. The

experimental goal is Click-Through-Rate (CTR) on the homepage

of Mobile Taobao App. We implement the above graph embedding

methods and then generate a number of similar items for each

item as recommendation candidates. The final recommending

results on the homepage in Taobao (see Figure 1) is generated

by the ranking engine, which is implemented based on a deep

neural network model. We use the same method to rank the

candidate items in the experiment. As mentioned above, the quality

of the similar items directly affects the recommending results.

Therefore, the recommending performance, i.e., CTR, can represent

�

the effectiveness of different methods in the matching stage. We

deploy the four methods in an A/B test framework and the results

of seven days in November 2017 are shown in Figure 4. Note that

“Base” represents an item-based CF method which has been widely

used in Taobao before graph embedding methods was deployed.

It calculates the similarity between two items according to item

co-occurrence and user voting weight. The similarity measurement

is well-tuned and suitable for Taobao’s business.

From Figure 4, we can see that EGES and GES outperform

BGE and Base consistently in terms of CTR, which demonstrates

the effectiveness of the incorporation of side information in

graph embedding. Further, the CTR of Base is larger than that

of BGE. It means that well-tuned CF based methods can beat

simple embedding method because a large number of hand-crafted

heuristic strategies have been exploited in practice. On the other

hand, EGES outperforms GES consistently, which aligns with the

results in the offline experimental results in Section 3.1. It further

demonstrates that weighted aggregation of side information is

better than average aggregation.

3.3 Case Study

In this section, we present some real-world cases in Taobao to

illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed methods. The cases are

examined in three aspects: 1) visualization of the embeddings by

EGES, 2) cold start items, and 3) weights in EGES.

3.3.1 Visualization. In this part, we visualize the embeddings

of items learned by EGES. We use the visualization tool provided

by tensorflow4. The results are shown in Figure 7. From Figure 7

(a), we can see that shoes of different categories are in separate

clusters. Here one color represents one category of shoes, like

badminton, table tennis, or football shoes. It demonstrates the

effectiveness of the learned embeddings with incorporation of side

information, i.e., items with similar side information should be

closer in the embedding space. From Figure 7 (b), we further analyze

the embeddings of three kinds of shoes: badminton, table tennis, and

football. It is very interesting to observe that badminton and table

tennis shoes are closer to each other while football shoes are farther

in the embedding space. This can be explained by a phenomenon

that people in China who like table tennis have much overlapping

with those who like badminton. However, those who like football

are quite different from those who like indoor sports, i.e., table

tennis and badminton. In this sense, recommending badminton

shoes to those who have viewed table tennis shoes is much better

than recommending football shoes.

3.3.2 Cold Start Items. In this part, we show the quality of the

embeddings of cold start items. For a newly updated item in Taobao,

no embedding can be learned from the item graph, and previous

CF based methods also fail in handling cold start items. Thus, we

represent a cold start item with the average embeddings of its side

information. Then, we retrieve the most similar items from the

existing items based on the dot product of the embeddings of two

items. The results are shown in Figure 5. We can see that despite the

missing of users’ behaviors for the two cold start items, different side

information can be utilized to learn their embeddings effectively

4http://projector.tensorflow.org/

Figure 5: Similar items for cold start items. Top 4 similar

items are shown. Note that “cat” means category.

in terms of the quality of the top similar items. In the figure,

we annotate for each similar item the types of side information

connected to the cold start item. We can see that the shops of the

items are very informative for measuring the similarity of two

items, which also aligns with the weight of each side information

in the following part.

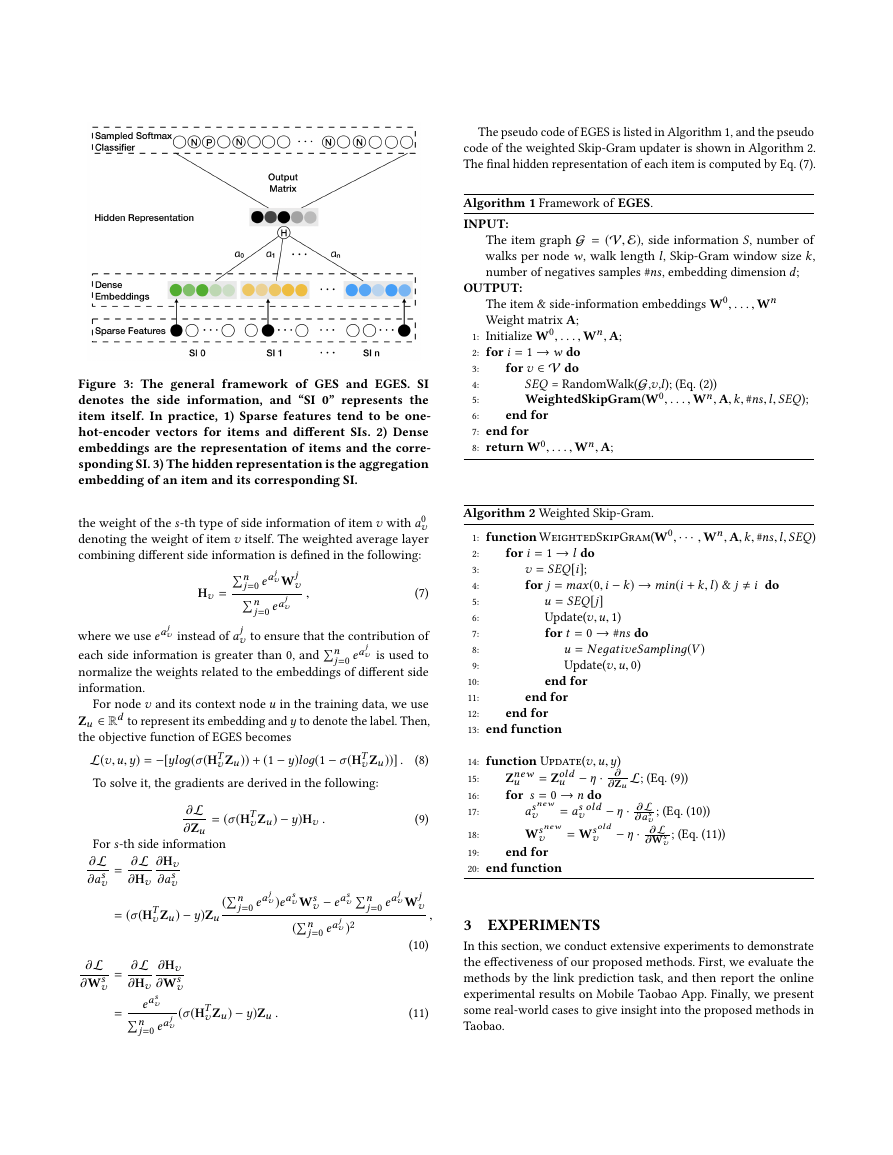

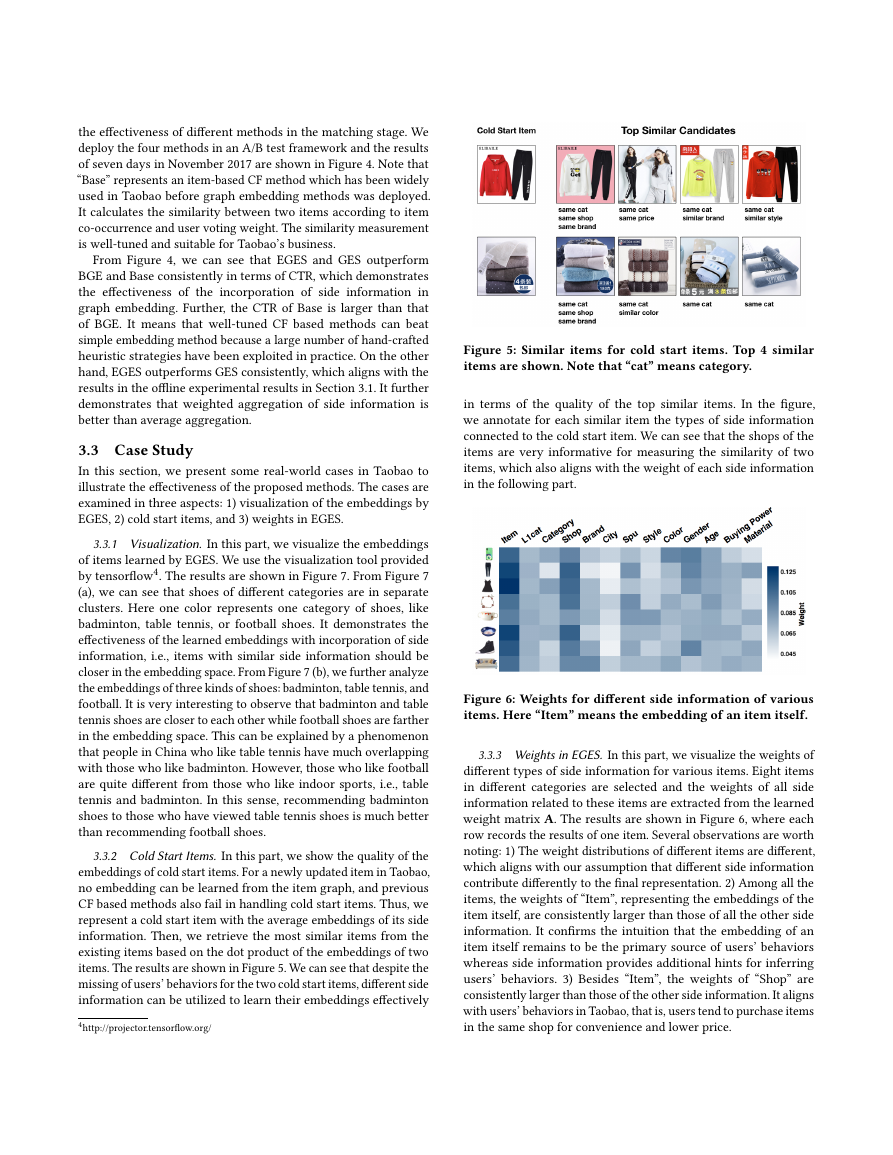

Figure 6: Weights for different side information of various

items. Here “Item” means the embedding of an item itself.

3.3.3 Weights in EGES. In this part, we visualize the weights of

different types of side information for various items. Eight items

in different categories are selected and the weights of all side

information related to these items are extracted from the learned

weight matrix A. The results are shown in Figure 6, where each

row records the results of one item. Several observations are worth

noting: 1) The weight distributions of different items are different,

which aligns with our assumption that different side information

contribute differently to the final representation. 2) Among all the

items, the weights of “Item”, representing the embeddings of the

item itself, are consistently larger than those of all the other side

information. It confirms the intuition that the embedding of an

item itself remains to be the primary source of users’ behaviors

whereas side information provides additional hints for inferring

users’ behaviors. 3) Besides “Item”, the weights of “Shop” are

consistently larger than those of the other side information. It aligns

with users’ behaviors in Taobao, that is, users tend to purchase items

in the same shop for convenience and lower price.

�

(a) Visualization of sports shoes of all categories.

(b) Visualization of badminton, table tennis and football shoes. Items in

gray do not belong to any of the three categories.

Figure 7: Visualization of the learned embeddings of a set of randomly chosen shoes. Item embeddings are projected into a

2-D plane via principal component analysis (PCA). Different colors represent different categories. Items in the same category

are grouped together.

4 SYSTEM DEPLOYMENT AND OPERATION

In this section, we introduce the implementation and deployment

of the proposed graph embedding methods in Taobao. We first give

a high-level introduction of the whole recommending platform

powering Taobao and then elaborate on the modules relevant to

our embedding methods.

• Users’ behaviors during their visits in Taobao are collected

and saved as log data for the offline subsystem.

The workflow of the offline subsystem, where graph embedding

methods are implemented and deployed, is described in the

following:

• The logs including users’ behaviors are retrieved. The item

graph is constructed based on the users’ behaviors. In

practice, we choose the logs in the recent three months.

Before generating session-based users’ behavior sequences,

anti-spam processing is applied to the data. The remaining

logs contains about 600 billion entries. Then, the item

graph is constructed according to the method described in

Section 2.2.

• To run our graph embedding methods, two practical solu-

tions are adopted: 1) The whole graph is split into a number

of sub-graphs, which can be processed in parallel in Taobao’s

Open Data Processing Service (ODPS) distributed platform.

There are around 50 million nodes in each subgraph. 2) To

generate the random walk sequences in the graph, we use

our iteration-based distributed graph framework in ODPS.

The total number of generated sequences by random walk

is around 150 billion.

• To implement the proposed embedding algorithms, 100

GPUs are used in our XTF platform. On the deployed

platform, with 150 billion samples, all modules in the offline

subsystem, including log retrieval, anti-spam processing,

item graph construction, sequence generation by random

walk, embedding, item-to-item similarity computation and

map generation, can be executed in less than six hours.

Thus, our recommending service can respond to users’ latest

behaviors in a very short time.

Figure 8: Architecture of the recommending platform in

Taobao.

In Figure 8, we show the architecture of the recommending

platform in Taobao. The platform consists of two subsystems: online

and offline. For the online subsystem, the main components are

Taobao Personality Platform (TPP) and Ranking Service Platform

(RSP). A typical workflow is illustrated in the following:

• When a user launches Mobile Taobao App, TPP extracts

the user’s latest information and retrieves a candidate set of

items from the offline subsystem, which is then fed to RSP.

RSP ranks the candidate set of items with a fine-tuned deep

neural net model and returns the ranked results to TPP.

�

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc

2023年江西萍乡中考道德与法治真题及答案.doc 2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc

2012年重庆南川中考生物真题及答案.doc 2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc

2013年江西师范大学地理学综合及文艺理论基础考研真题.doc 2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc

2020年四川甘孜小升初语文真题及答案I卷.doc 2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc

2020年注册岩土工程师专业基础考试真题及答案.doc 2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc

2023-2024学年福建省厦门市九年级上学期数学月考试题及答案.doc 2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc

2021-2022学年辽宁省沈阳市大东区九年级上学期语文期末试题及答案.doc 2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc

2022-2023学年北京东城区初三第一学期物理期末试卷及答案.doc 2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc

2018上半年江西教师资格初中地理学科知识与教学能力真题及答案.doc 2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc

2012年河北国家公务员申论考试真题及答案-省级.doc 2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc

2020-2021学年江苏省扬州市江都区邵樊片九年级上学期数学第一次质量检测试题及答案.doc 2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc

2022下半年黑龙江教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案.doc