To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

Our gain in net worth during 1989 was $1.515 billion, or

44.4%. Over the last 25 years (that is, since present management

took over) our per-share book value has grown from $19.46 to

$4,296.01, or at a rate of 23.8% compounded annually.

What counts, however, is intrinsic value - the figure

indicating what all of our constituent businesses are rationally

worth. With perfect foresight, this number can be calculated by

taking all future cash flows of a business - in and out - and

discounting them at prevailing interest rates. So valued, all

businesses, from manufacturers of buggy whips to operators of

cellular phones, become economic equals.

Back when Berkshire's book value was $19.46, intrinsic

value was somewhat less because the book value was entirely tied

up in a textile business not worth the figure at which it was

carried. Now most of our businesses are worth far more than their

carrying values. This agreeable evolution from a discount to a

premium means that Berkshire's intrinsic business value has

compounded at a rate that somewhat exceeds our 23.8% annual

growth in book value.

The rear-view mirror is one thing; the windshield is

another. A large portion of our book value is represented by

equity securities that, with minor exceptions, are carried on our

balance sheet at current market values. At yearend these

securities were valued at higher prices, relative to their own

intrinsic business values, than has been the case in the past.

One reason is the buoyant 1989 stock market. More important, the

virtues of these businesses have been widely recognized. Whereas

once their stock prices were inappropriately low, they are not

now.

We will keep most of our major holdings, regardless of how

they are priced relative to intrinsic business value. This 'til-

death-do-us-part attitude, combined with the full prices these

holdings command, means that they cannot be expected to push up

Berkshire's value in the future as sharply as in the past. In

other words, our performance to date has benefited from a double-

dip: (1) the exceptional gains in intrinsic value that our

portfolio companies have achieved; (2) the additional bonus we

realized as the market appropriately "corrected" the prices of

these companies, raising their valuations in relation to those of

the average business. We will continue to benefit from good gains

in business value that we feel confident our portfolio companies

will make. But our "catch-up" rewards have been realized, which

means we'll have to settle for a single-dip in the future.

We face another obstacle: In a finite world, high growth

rates must self-destruct. If the base from which the growth is

taking place is tiny, this law may not operate for a time. But

when the base balloons, the party ends: A high growth rate

eventually forges its own anchor.

Carl Sagan has entertainingly described this phenomenon,

musing about the destiny of bacteria that reproduce by dividing

into two every 15 minutes. Says Sagan: "That means four doublings

an hour, and 96 doublings a day. Although a bacterium weighs only

about a trillionth of a gram, its descendants, after a day of

wild asexual abandon, will collectively weigh as much as a

mountain...in two days, more than the sun - and before very long,

everything in the universe will be made of bacteria." Not to

B

E

R

K

S

H

I

R

E

H

A

T

H

A

W

A

Y

I

N

C

.

�

worry, says Sagan: Some obstacle always impedes this kind of

exponential growth. "The bugs run out of food, or they poison

each other, or they are shy about reproducing in public."

Even on bad days, Charlie Munger (Berkshire's Vice Chairman

and my partner) and I do not think of Berkshire as a bacterium.

Nor, to our unending sorrow, have we found a way to double its

net worth every 15 minutes. Furthermore, we are not the least bit

shy about reproducing - financially - in public. Nevertheless,

Sagan's observations apply. From Berkshire's present base of $4.9

billion in net worth, we will find it much more difficult to

average 15% annual growth in book value than we did to average

23.8% from the $22 million we began with.

Taxes

Our 1989 gain of $1.5 billion was achieved after we took a

charge of about $712 million for income taxes. In addition,

Berkshire's share of the income taxes paid by its five major

investees totaled about $175 million.

Of this year's tax charge, about $172 million will be paid

currently; the remainder, $540 million, is deferred. Almost all

of the deferred portion relates to the 1989 increase in

unrealized profits in our common stock holdings. Against this

increase, we have reserved a 34% tax.

We also carry reserves at that rate against all unrealized

profits generated in 1987 and 1988. But, as we explained last

year, the unrealized gains we amassed before 1987 - about $1.2

billion - carry reserves booked at the 28% tax rate that then

prevailed.

A new accounting rule is likely to be adopted that will

require companies to reserve against all gains at the current tax

rate, whatever it may be. With the rate at 34%, such a rule would

increase our deferred tax liability, and decrease our net worth,

by about $71 million - the result of raising the reserve on our

pre-1987 gain by six percentage points. Because the proposed rule

has sparked widespread controversy and its final form is unclear,

we have not yet made this change.

As you can see from our balance sheet on page 27, we would

owe taxes of more than $1.1 billion were we to sell all of our

securities at year-end market values. Is this $1.1 billion

liability equal, or even similar, to a $1.1 billion liability

payable to a trade creditor 15 days after the end of the year?

Obviously not - despite the fact that both items have exactly the

same effect on audited net worth, reducing it by $1.1 billion.

On the other hand, is this liability for deferred taxes a

meaningless accounting fiction because its payment can be

triggered only by the sale of stocks that, in very large part, we

have no intention of selling? Again, the answer is no.

In economic terms, the liability resembles an interest-free

loan from the U.S. Treasury that comes due only at our election

(unless, of course, Congress moves to tax gains before they are

realized). This "loan" is peculiar in other respects as well: It

can be used only to finance the ownership of the particular,

appreciated stocks and it fluctuates in size - daily as market

prices change and periodically if tax rates change. In effect,

this deferred tax liability is equivalent to a very large

transfer tax that is payable only if we elect to move from one

asset to another. Indeed, we sold some relatively small holdings

in 1989, incurring about $76 million of "transfer" tax on $224

million of gains.

Because of the way the tax law works, the Rip Van Winkle

�

style of investing that we favor - if successful - has an

important mathematical edge over a more frenzied approach. Let's

look at an extreme comparison.

Imagine that Berkshire had only $1, which we put in a

security that doubled by yearend and was then sold. Imagine

further that we used the after-tax proceeds to repeat this

process in each of the next 19 years, scoring a double each time.

At the end of the 20 years, the 34% capital gains tax that we

would have paid on the profits from each sale would have

delivered about $13,000 to the government and we would be left

with about $25,250. Not bad. If, however, we made a single

fantastic investment that itself doubled 20 times during the 20

years, our dollar would grow to $1,048,576. Were we then to cash

out, we would pay a 34% tax of roughly $356,500 and be left with

about $692,000.

The sole reason for this staggering difference in results

would be the timing of tax payments. Interestingly, the

government would gain from Scenario 2 in exactly the same 27:1

ratio as we - taking in taxes of $356,500 vs. $13,000 - though,

admittedly, it would have to wait for its money.

We have not, we should stress, adopted our strategy

favoring long-term investment commitments because of these

mathematics. Indeed, it is possible we could earn greater after-

tax returns by moving rather frequently from one investment to

another. Many years ago, that's exactly what Charlie and I did.

Now we would rather stay put, even if that means slightly

lower returns. Our reason is simple: We have found splendid

business relationships to be so rare and so enjoyable that we

want to retain all we develop. This decision is particularly

easy for us because we feel that these relationships will produce

good - though perhaps not optimal - financial results.

Considering that, we think it makes little sense for us to give

up time with people we know to be interesting and admirable for

time with others we do not know and who are likely to have human

qualities far closer to average. That would be akin to marrying

for money - a mistake under most circumstances, insanity if one

is already rich.

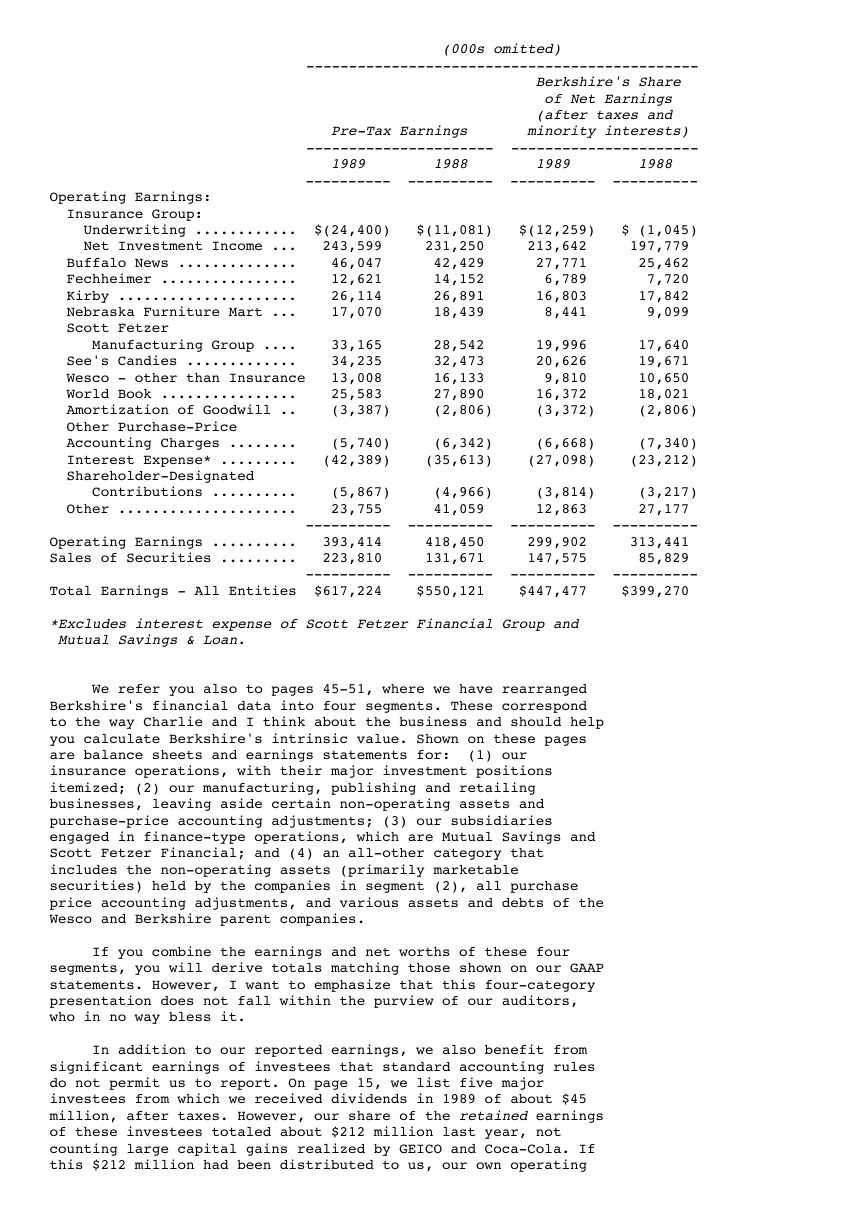

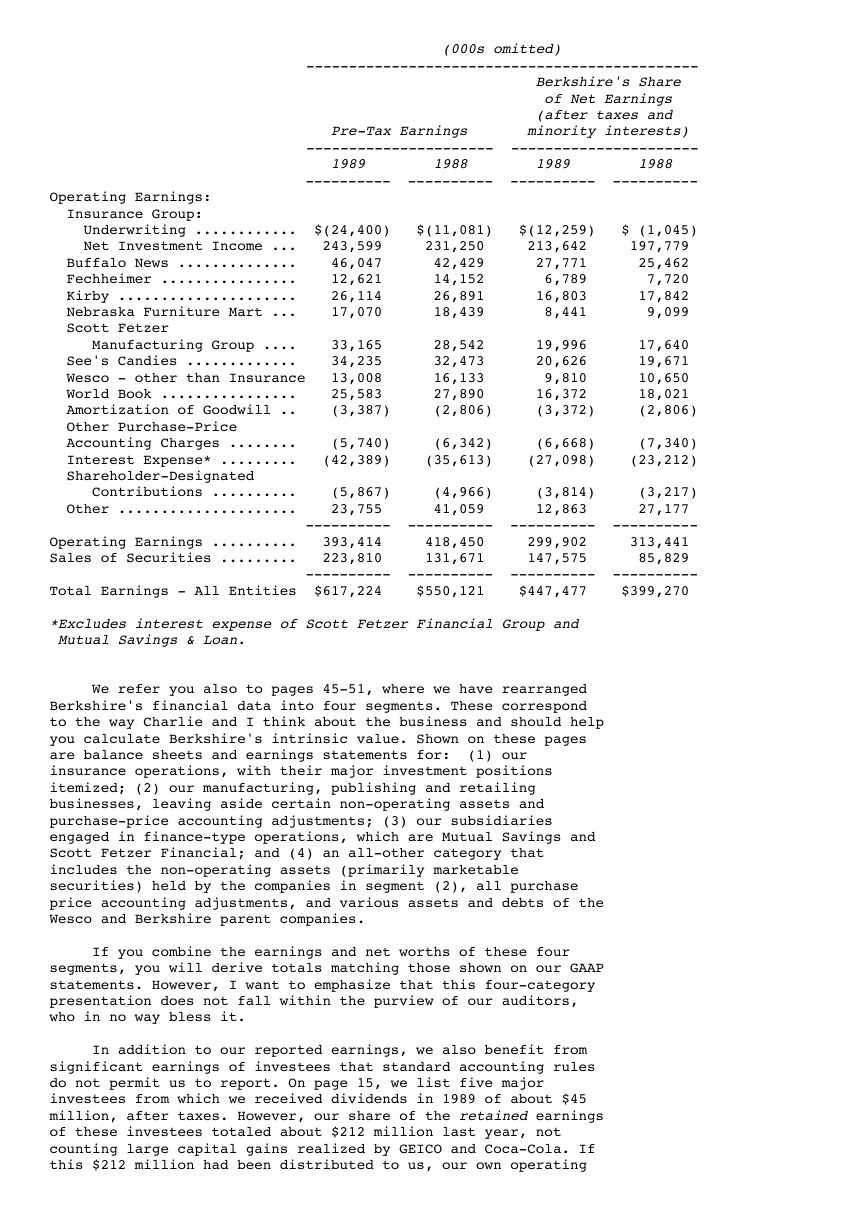

Sources of Reported Earnings

The table below shows the major sources of Berkshire's

reported earnings. In this presentation, amortization of Goodwill

and other major purchase-price accounting adjustments are not

charged against the specific businesses to which they apply, but

are instead aggregated and shown separately. This procedure lets

you view the earnings of our businesses as they would have been

reported had we not purchased them. I've explained in past

reports why this form of presentation seems to us to be more

useful to investors and managers than one utilizing generally

accepted accounting principles (GAAP), which require purchase-

price adjustments to be made on a business-by-business basis. The

total net earnings we show in the table are, of course, identical

to the GAAP total in our audited financial statements.

Further information about these businesses is given in the

Business Segment section on pages 37-39, and in the Management's

Discussion section on pages 40-44. In these sections you also

will find our segment earnings reported on a GAAP basis. For

information on Wesco's businesses, I urge you to read Charlie

Munger's letter, which starts on page 54. In addition, we have

reprinted on page 71 Charlie's May 30, 1989 letter to the U. S.

League of Savings Institutions, which conveyed our disgust with

its policies and our consequent decision to resign.

�

(000s omitted)

----------------------------------------------

Berkshire's Share

of Net Earnings

(after taxes and

Pre-Tax Earnings minority interests)

---------------------- ----------------------

1989 1988 1989 1988

---------- ---------- ---------- ----------

Operating Earnings:

Insurance Group:

Underwriting ............ $(24,400) $(11,081) $(12,259) $ (1,045)

Net Investment Income ... 243,599 231,250 213,642 197,779

Buffalo News .............. 46,047 42,429 27,771 25,462

Fechheimer ................ 12,621 14,152 6,789 7,720

Kirby ..................... 26,114 26,891 16,803 17,842

Nebraska Furniture Mart ... 17,070 18,439 8,441 9,099

Scott Fetzer

Manufacturing Group .... 33,165 28,542 19,996 17,640

See's Candies ............. 34,235 32,473 20,626 19,671

Wesco - other than Insurance 13,008 16,133 9,810 10,650

World Book ................ 25,583 27,890 16,372 18,021

Amortization of Goodwill .. (3,387) (2,806) (3,372) (2,806)

Other Purchase-Price

Accounting Charges ........ (5,740) (6,342) (6,668) (7,340)

Interest Expense* ......... (42,389) (35,613) (27,098) (23,212)

Shareholder-Designated

Contributions .......... (5,867) (4,966) (3,814) (3,217)

Other ..................... 23,755 41,059 12,863 27,177

---------- ---------- ---------- ----------

Operating Earnings .......... 393,414 418,450 299,902 313,441

Sales of Securities ......... 223,810 131,671 147,575 85,829

---------- ---------- ---------- ----------

Total Earnings - All Entities $617,224 $550,121 $447,477 $399,270

*Excludes interest expense of Scott Fetzer Financial Group and

Mutual Savings & Loan.

We refer you also to pages 45-51, where we have rearranged

Berkshire's financial data into four segments. These correspond

to the way Charlie and I think about the business and should help

you calculate Berkshire's intrinsic value. Shown on these pages

are balance sheets and earnings statements for: (1) our

insurance operations, with their major investment positions

itemized; (2) our manufacturing, publishing and retailing

businesses, leaving aside certain non-operating assets and

purchase-price accounting adjustments; (3) our subsidiaries

engaged in finance-type operations, which are Mutual Savings and

Scott Fetzer Financial; and (4) an all-other category that

includes the non-operating assets (primarily marketable

securities) held by the companies in segment (2), all purchase

price accounting adjustments, and various assets and debts of the

Wesco and Berkshire parent companies.

If you combine the earnings and net worths of these four

segments, you will derive totals matching those shown on our GAAP

statements. However, I want to emphasize that this four-category

presentation does not fall within the purview of our auditors,

who in no way bless it.

In addition to our reported earnings, we also benefit from

significant earnings of investees that standard accounting rules

do not permit us to report. On page 15, we list five major

investees from which we received dividends in 1989 of about $45

million, after taxes. However, our share of the retained earnings

of these investees totaled about $212 million last year, not

counting large capital gains realized by GEICO and Coca-Cola. If

this $212 million had been distributed to us, our own operating

�

earnings, after the payment of additional taxes, would have been

close to $500 million rather than the $300 million shown in the

table.

The question you must decide is whether these undistributed

earnings are as valuable to us as those we report. We believe

they are - and even think they may be more valuable. The reason

for this a-bird-in-the-bush-may-be-worth-two-in-the-hand

conclusion is that earnings retained by these investees will

be deployed by talented, owner-oriented managers who

sometimes have better uses for these funds in their own

businesses than we would have in ours. I would not make such a

generous assessment of most managements, but it is appropriate in

these cases.

In our view, Berkshire's fundamental earning power is best

measured by a "look-through" approach, in which we append our

share of the operating earnings retained by our investees to our

own reported operating earnings, excluding capital gains in both

instances. For our intrinsic business value to grow at an average

of 15% per year, our "look-through" earnings must grow at about

the same pace. We'll need plenty of help from our present

investees, and also need to add a new one from time to time, in

order to reach this 15% goal.

Non-Insurance Operations

In the past, we have labeled our major manufacturing,

publishing and retail operations "The Sainted Seven." With our

acquisition of Borsheim's early in 1989, the challenge was to

find a new title both alliterative and appropriate. We failed:

Let's call the group "The Sainted Seven Plus One."

This divine assemblage - Borsheim's, The Buffalo News,

Fechheimer Bros., Kirby, Nebraska Furniture Mart, Scott Fetzer

Manufacturing Group, See's Candies, World Book - is a collection

of businesses with economic characteristics that range from good

to superb. Its managers range from superb to superb.

Most of these managers have no need to work for a living;

they show up at the ballpark because they like to hit home runs.

And that's exactly what they do. Their combined financial

statements (including those of some smaller operations), shown on

page 49, illustrate just how outstanding their performance is. On

an historical accounting basis, after-tax earnings of these

operations were 57% on average equity capital. Moreover, this

return was achieved with no net leverage: Cash equivalents have

matched funded debt. When I call off the names of our managers -

the Blumkin, Friedman and Heldman families, Chuck Huggins, Stan

Lipsey, and Ralph Schey - I feel the same glow that Miller

Huggins must have experienced when he announced the lineup of his

1927 New York Yankees.

Let's take a look, business by business:

o In its first year with Berkshire, Borsheim's met all

expectations. Sales rose significantly and are now considerably

better than twice what they were four years ago when the company

moved to its present location. In the six years prior to the

move, sales had also doubled. Ike Friedman, Borsheim's managing

genius - and I mean that - has only one speed: fast-forward.

If you haven't been there, you've never seen a jewelry store

like Borsheim's. Because of the huge volume it does at one

location, the store can maintain an enormous selection across all

price ranges. For the same reason, it can hold its expense ratio

to about one-third that prevailing at jewelry stores offering

comparable merchandise. The store's tight control of expenses,

�

accompanied by its unusual buying power, enable it to offer

prices far lower than those of other jewelers. These prices, in

turn, generate even more volume, and so the circle goes 'round

and 'round. The end result is store traffic as high as 4,000

people on seasonally-busy days.

Ike Friedman is not only a superb businessman and a great

showman but also a man of integrity. We bought the business

without an audit, and all of our surprises have been on the plus

side. "If you don't know jewelry, know your jeweler" makes sense

whether you are buying the whole business or a tiny diamond.

A story will illustrate why I enjoy Ike so much: Every two

years I'm part of an informal group that gathers to have fun and

explore a few subjects. Last September, meeting at Bishop's Lodge

in Santa Fe, we asked Ike, his wife Roz, and his son Alan to come

by and educate us on jewels and the jewelry business.

Ike decided to dazzle the group, so he brought from Omaha

about $20 million of particularly fancy merchandise. I was

somewhat apprehensive - Bishop's Lodge is no Fort Knox - and I

mentioned my concern to Ike at our opening party the evening

before his presentation. Ike took me aside. "See that safe?" he

said. "This afternoon we changed the combination and now even the

hotel management doesn't know what it is." I breathed easier. Ike

went on: "See those two big fellows with guns on their hips?

They'll be guarding the safe all night." I now was ready to

rejoin the party. But Ike leaned closer: "And besides, Warren,"

he confided, "the jewels aren't in the safe."

How can we miss with a fellow like that - particularly when

he comes equipped with a talented and energetic family, Alan,

Marvin Cohn, and Don Yale.

o At See's Candies we had an 8% increase in pounds sold, even

though 1988 was itself a record year. Included in the 1989

performance were excellent same-store poundage gains, our first

in many years.

Advertising played an important role in this outstanding

performance. We increased total advertising expenditures from $4

million to $5 million and also got copy from our agency, Hal

Riney & Partners, Inc., that was 100% on the money in conveying

the qualities that make See's special.

In our media businesses, such as the Buffalo News, we sell

advertising. In other businesses, such as See's, we are buyers.

When we buy, we practice exactly what we preach when we sell. At

See's, we more than tripled our expenditures on newspaper

advertising last year, to the highest percentage of sales that I

can remember. The payoff was terrific, and we thank both Hal

Riney and the power of well-directed newspaper advertising for

this result.

See's splendid performances have become routine. But there

is nothing routine about the management of Chuck Huggins: His

daily involvement with all aspects of production and sales

imparts a quality-and-service message to the thousands of

employees we need to produce and distribute over 27 million

pounds of candy annually. In a company with 225 shops and a

massive mail order and phone business, it is no small trick to

run things so that virtually every customer leaves happy. Chuck

makes it look easy.

o The Nebraska Furniture Mart had record sales and excellent

earnings in 1989, but there was one sad note. Mrs. B - Rose

Blumkin, who started the company 52 years ago with $500 - quit in

May, after disagreeing with other members of the Blumkin

family/management about the remodeling and operation of the

�

carpet department.

Mrs. B probably has made more smart business decisions than

any living American, but in this particular case I believe the

other members of the family were entirely correct: Over the past

three years, while the store's other departments increased sales

by 24%, carpet sales declined by 17% (but not because of any lack

of sales ability by Mrs. B, who has always personally sold far

more merchandise than any other salesperson in the store).

You will be pleased to know that Mrs. B continues to make

Horatio Alger's heroes look like victims of tired blood. At age

96 she has started a new business selling - what else? - carpet

and furniture. And as always, she works seven days a week.

At the Mart Louie, Ron, and Irv Blumkin continue to propel

what is by far the largest and most successful home furnishings

store in the country. They are outstanding merchants, outstanding

managers, and a joy to be associated with. One reading on their

acumen: In the fourth quarter of 1989, the carpet department

registered a 75.3% consumer share in the Omaha market, up from

67.7% a year earlier and over six times that of its nearest

competitor.

NFM and Borsheim's follow precisely the same formula for

success: (1) unparalleled depth and breadth of merchandise at one

location; (2) the lowest operating costs in the business; (3) the

shrewdest of buying, made possible in part by the huge volumes

purchased; (4) gross margins, and therefore prices, far below

competitors'; and (5) friendly personalized service with family

members on hand at all times.

Another plug for newspapers: NFM increased its linage in the

local paper by over 20% in 1989 - off a record 1988 - and remains

the paper's largest ROP advertiser by far. (ROP advertising is

the kind printed in the paper, as opposed to that in preprinted

inserts.) To my knowledge, Omaha is the only city in which a home

furnishings store is the advertising leader. Many retailers cut

space purchases in 1989; our experience at See's and NFM would

indicate they made a major mistake.

o The Buffalo News continued to star in 1989 in three

important ways: First, among major metropolitan papers, both

daily and Sunday, the News is number one in household penetration

- the percentage of local households that purchase it each day.

Second, in "news hole" - the portion of the paper devoted to news

- the paper stood at 50.1% in 1989 vs. 49.5% in 1988, a level

again making it more news-rich than any comparable American

paper. Third, in a year that saw profits slip at many major

papers, the News set its seventh consecutive profit record.

To some extent, these three factors are related, though

obviously a high-percentage news hole, by itself, reduces profits

significantly. A large and intelligently-utilized news hole,

however, attracts a wide spectrum of readers and thereby boosts

penetration. High penetration, in turn, makes a newspaper

particularly valuable to retailers since it allows them to talk

to the entire community through a single "megaphone." A low-

penetration paper is a far less compelling purchase for many

advertisers and will eventually suffer in both ad rates and

profits.

It should be emphasized that our excellent penetration is

neither an accident nor automatic. The population of Erie County,

home territory of the News, has been falling - from 1,113,000 in

1970 to 1,015,000 in 1980 to an estimated 966,000 in 1988.

Circulation figures tell a different story. In 1975, shortly

before we started our Sunday edition, the Courier-Express, a

long-established Buffalo paper, was selling 207,500 Sunday copies

�

in Erie County. Last year - with population at least 5% lower -

the News sold an average of 292,700 copies. I believe that in no

other major Sunday market has there been anything close to that

increase in penetration.

When this kind of gain is made - and when a paper attains an

unequaled degree of acceptance in its home town - someone is

doing something right. In this case major credit clearly belongs

to Murray Light, our long-time editor who daily creates an

informative, useful, and interesting product. Credit should go

also to the Circulation and Production Departments: A paper that

is frequently late, because of production problems or

distribution weaknesses, will lose customers, no matter how

strong its editorial content.

Stan Lipsey, publisher of the News, has produced profits

fully up to the strength of our product. I believe Stan's

managerial skills deliver at least five extra percentage points

in profit margin compared to the earnings that would be achieved

by an average manager given the same circumstances. That is an

amazing performance, and one that could only be produced by a

talented manager who knows - and cares - about every nut and bolt

of the business.

Stan's knowledge and talents, it should be emphasized,

extend to the editorial product. His early years in the business

were spent on the news side and he played a key role in

developing and editing a series of stories that in 1972 won a

Pulitzer Prize for the Sun Newspaper of Omaha. Stan and I have

worked together for over 20 years, through some bad times as well

as good, and I could not ask for a better partner.

o At Fechheimer, the Heldman clan - Bob, George, Gary,

Roger and Fred - continue their extraordinary performance. Profits

in 1989 were down somewhat because of problems the business

experienced in integrating a major 1988 acquisition. These

problems will be ironed out in time. Meanwhile, return on invested

capital at Fechheimer remains splendid.

Like all of our managers, the Heldmans have an exceptional

command of the details of their business. At last year's annual

meeting I mentioned that when a prisoner enters San Quentin, Bob

and George probably know his shirt size. That's only a slight

exaggeration: No matter what area of the country is being

discussed, they know exactly what is going on with major

customers and with the competition.

Though we purchased Fechheimer four years ago, Charlie and I

have never visited any of its plants or the home office in

Cincinnati. We're much like the lonesome Maytag repairman: The

Heldman managerial product is so good that a service call is

never needed.

o Ralph Schey continues to do a superb job in managing

our largest group - World Book, Kirby, and the Scott Fetzer

Manufacturing Companies. Aggregate earnings of these businesses

have increased every year since our purchase and returns on

invested capital continue to be exceptional. Ralph is running an

enterprise large enough, were it standing alone, to be on the

Fortune 500. And he's running it in a fashion that would put him

high in the top decile, measured by return on equity.

For some years, World Book has operated out of a single

location in Chicago's Merchandise Mart. Anticipating the imminent

expiration of its lease, the business is now decentralizing into

four locations. The expenses of this transition are significant;

nevertheless profits in 1989 held up well. It will be another

year before costs of the move are fully behind us.

�