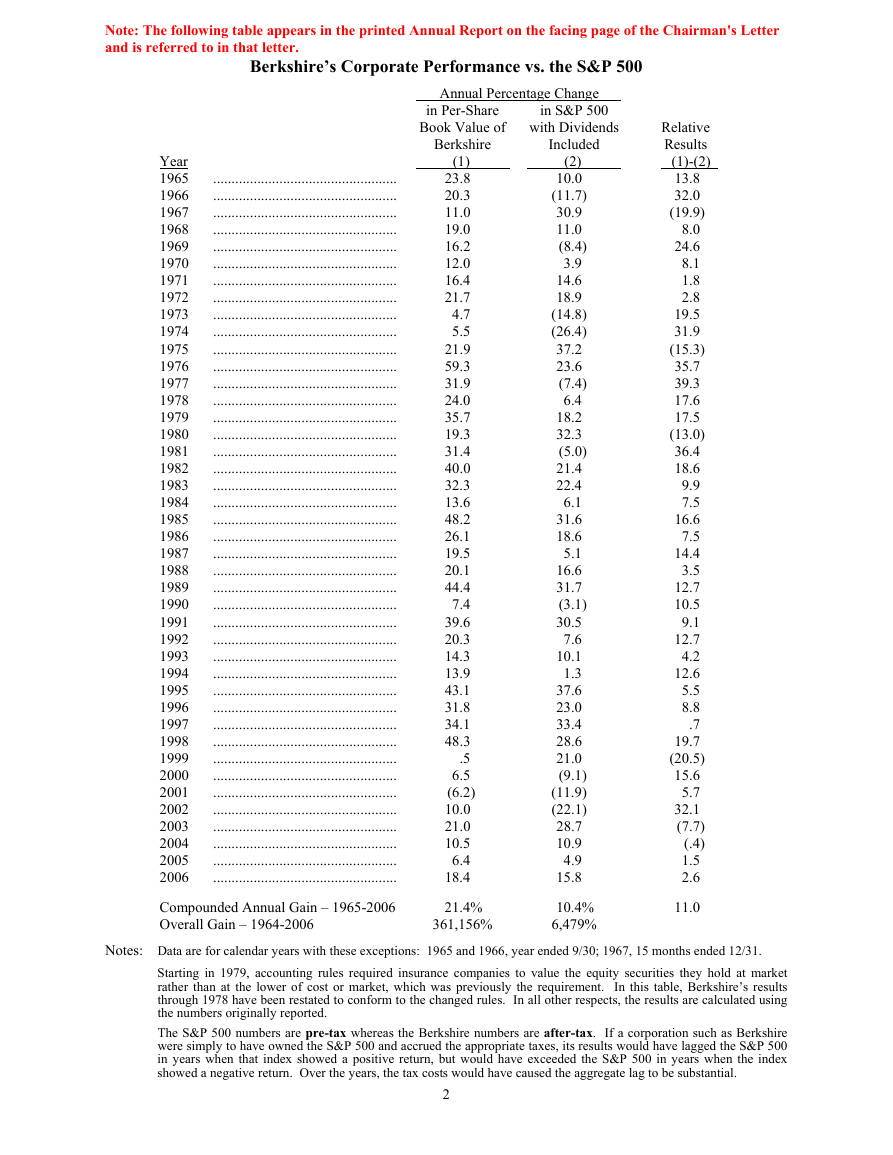

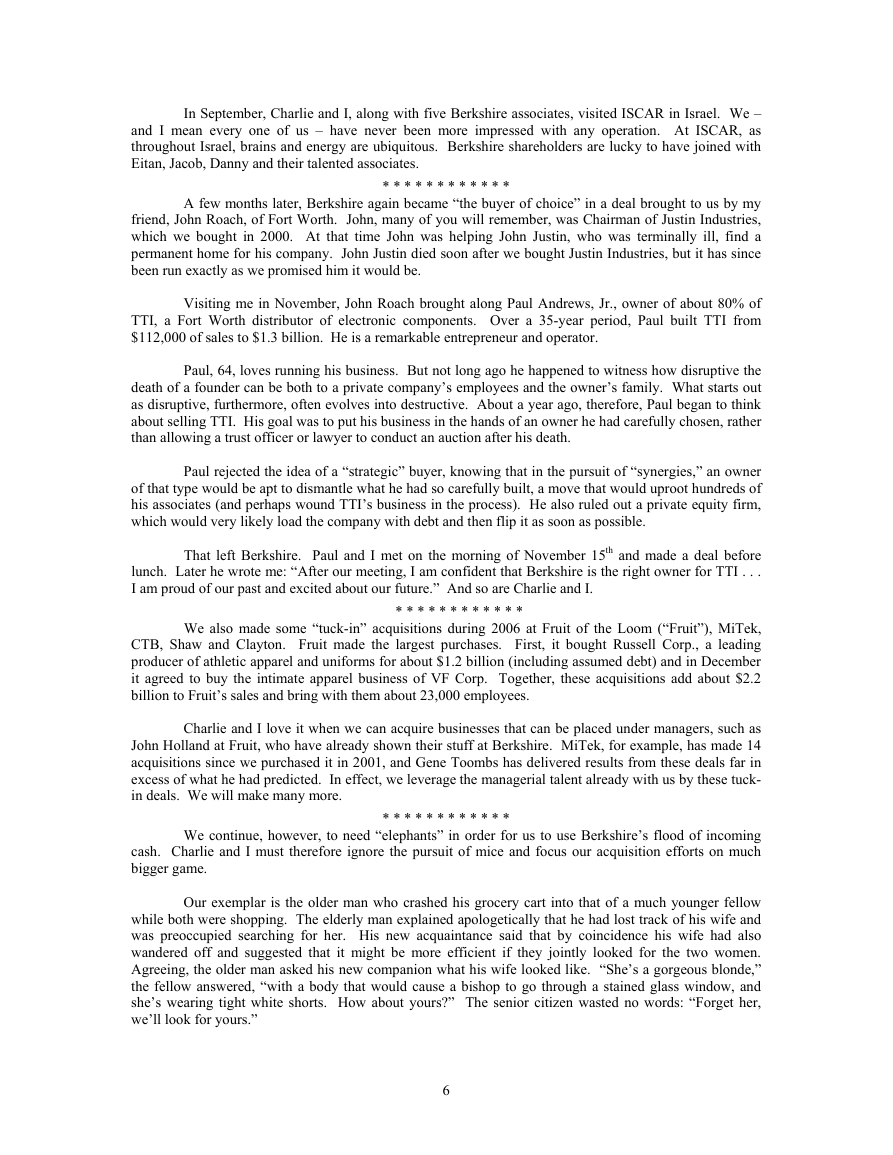

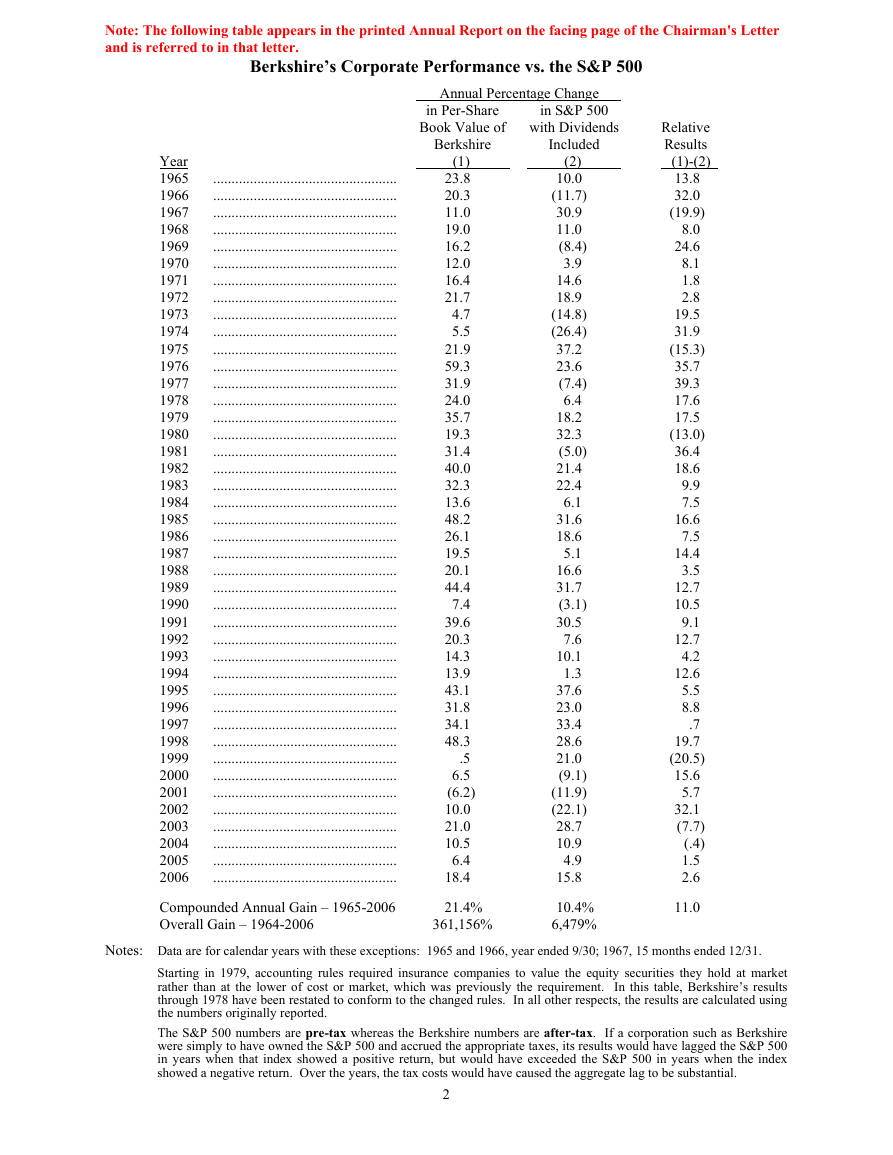

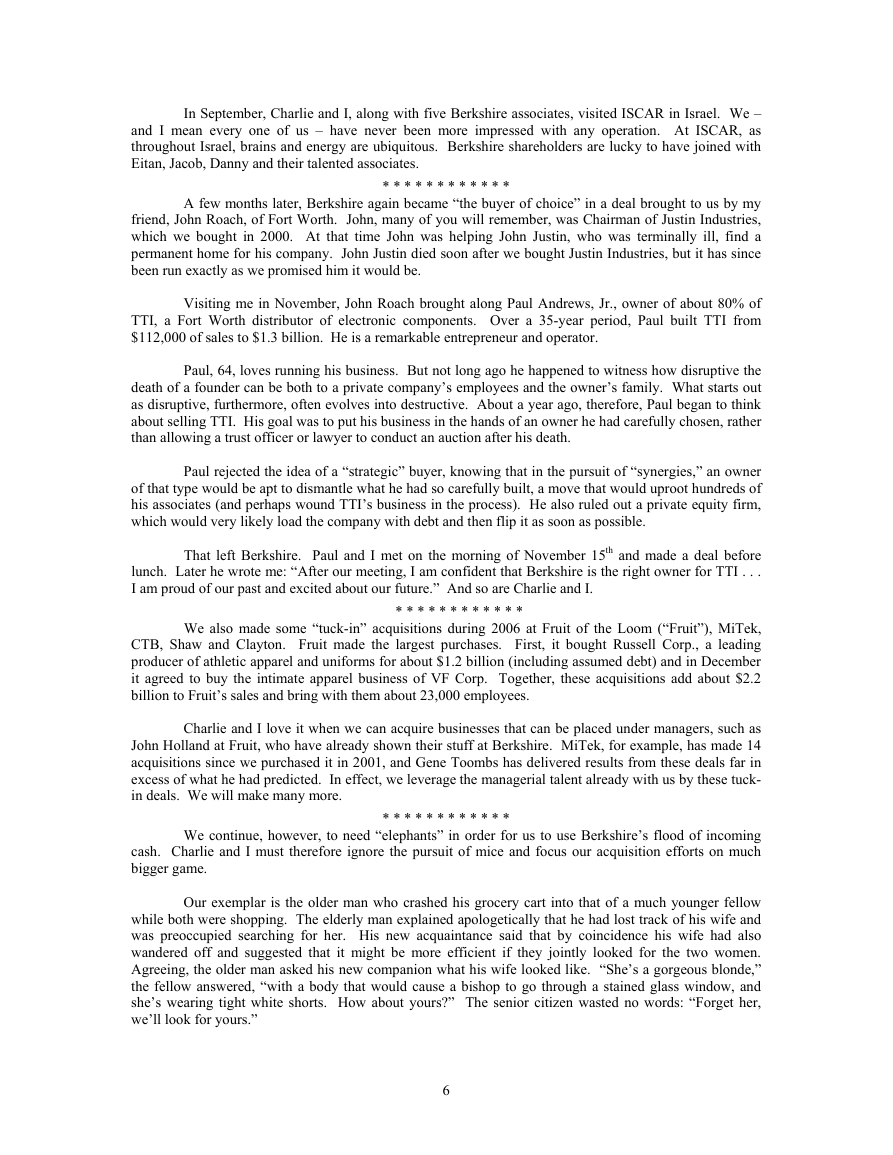

Note: The following table appears in the printed Annual Report on the facing page of the Chairman's Letter

and is referred to in that letter.

Berkshire’s Corporate Performance vs. the S&P 500

Annual Percentage Change

in S&P 500

in Per-Share

Book Value of with Dividends

Berkshire

Included

Year

1965

1966

1967

1968

1969

1970

1971

1972

1973

1974

1975

1976

1977

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

..................................................

(1)

23.8

20.3

11.0

19.0

16.2

12.0

16.4

21.7

4.7

5.5

21.9

59.3

31.9

24.0

35.7

19.3

31.4

40.0

32.3

13.6

48.2

26.1

19.5

20.1

44.4

7.4

39.6

20.3

14.3

13.9

43.1

31.8

34.1

48.3

.5

6.5

(6.2)

10.0

21.0

10.5

6.4

18.4

Relative

Results

(1)-(2)

13.8

32.0

(19.9)

8.0

24.6

8.1

1.8

2.8

19.5

31.9

(15.3)

35.7

39.3

17.6

17.5

(13.0)

36.4

18.6

9.9

7.5

16.6

7.5

14.4

3.5

12.7

10.5

9.1

12.7

4.2

12.6

5.5

8.8

.7

19.7

(20.5)

15.6

5.7

32.1

(7.7)

(.4)

1.5

2.6

(2)

10.0

(11.7)

30.9

11.0

(8.4)

3.9

14.6

18.9

(14.8)

(26.4)

37.2

23.6

(7.4)

6.4

18.2

32.3

(5.0)

21.4

22.4

6.1

31.6

18.6

5.1

16.6

31.7

(3.1)

30.5

7.6

10.1

1.3

37.6

23.0

33.4

28.6

21.0

(9.1)

(11.9)

(22.1)

28.7

10.9

4.9

15.8

Compounded Annual Gain – 1965-2006

Overall Gain – 1964-2006

21.4%

361,156%

10.4%

6,479%

11.0

Notes: Data are for calendar years with these exceptions: 1965 and 1966, year ended 9/30; 1967, 15 months ended 12/31.

Starting in 1979, accounting rules required insurance companies to value the equity securities they hold at market

rather than at the lower of cost or market, which was previously the requirement. In this table, Berkshire’s results

through 1978 have been restated to conform to the changed rules. In all other respects, the results are calculated using

the numbers originally reported.

The S&P 500 numbers are pre-tax whereas the Berkshire numbers are after-tax. If a corporation such as Berkshire

were simply to have owned the S&P 500 and accrued the appropriate taxes, its results would have lagged the S&P 500

in years when that index showed a positive return, but would have exceeded the S&P 500 in years when the index

showed a negative return. Over the years, the tax costs would have caused the aggregate lag to be substantial.

2

�

BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC.

To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

Our gain in net worth during 2006 was $16.9 billion, which increased the per-share book value of

both our Class A and Class B stock by 18.4%. Over the last 42 years (that is, since present management

took over) book value has grown from $19 to $70,281, a rate of 21.4% compounded annually.*

We believe that $16.9 billion is a record for a one-year gain in net worth – more than has ever

been booked by any American business, leaving aside boosts that have occurred because of mergers (e.g.,

AOL’s purchase of Time Warner). Of course, Exxon Mobil and other companies earn far more than

Berkshire, but their earnings largely go to dividends and/or repurchases, rather than to building net worth.

All that said, a confession about our 2006 gain is in order. Our most important business,

insurance, benefited from a large dose of luck: Mother Nature, bless her heart, went on vacation. After

hammering us with hurricanes in 2004 and 2005 – storms that caused us to lose a bundle on super-cat

insurance – she just vanished. Last year, the red ink from this activity turned black – very black.

In addition, the great majority of our 73 businesses did outstandingly well in 2006. Let me focus

for a moment on one of our largest operations, GEICO. What management accomplished there was simply

extraordinary.

As I’ve told you before, Tony Nicely, GEICO’s CEO, went to work at the company 45 years ago,

two months after turning 18. He became CEO in 1992, and from then on the company’s growth exploded.

In addition, Tony has delivered staggering productivity gains in recent years. Between yearend 2003 and

yearend 2006, the number of GEICO policies increased from 5.7 million to 8.1 million, a jump of 42%.

Yet during that same period, the company’s employees (measured on a fulltime-equivalent basis) fell 3.5%.

So productivity grew 47%. And GEICO didn’t start fat.

That remarkable gain has allowed GEICO to maintain its all-important position as a low-cost

producer, even though it has dramatically increased advertising expenditures. Last year GEICO spent $631

million on ads, up from $238 million in 2003 (and up from $31 million in 1995, when Berkshire took

control). Today, GEICO spends far more on ads than any of its competitors, even those much larger. We

will continue to raise the bar.

Last year I told you that if you had a new son or grandson to be sure to name him Tony. But Don

Keough, a Berkshire director, recently had a better idea. After reviewing GEICO’s performance in 2006,

he wrote me, “Forget births. Tell the shareholders to immediately change the names of their present

children to Tony or Antoinette.” Don signed his letter “Tony.”

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Charlie Munger – my partner and Berkshire’s vice chairman – and I run what has turned out to be

a big business, one with 217,000 employees and annual revenues approaching $100 billion. We certainly

didn’t plan it that way. Charlie began as a lawyer, and I thought of myself as a security analyst. Sitting in

those seats, we both grew skeptical about the ability of big entities of any type to function well. Size seems

to make many organizations slow-thinking, resistant to change and smug. In Churchill’s words: “We shape

our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us.” Here’s a telling fact: Of the ten non-oil companies

having the largest market capitalization in 1965 – titans such as General Motors, Sears, DuPont and

Eastman Kodak – only one made the 2006 list.

are 1/30th of those shown for the A.

*All per-share figures used in this report apply to Berkshire’s A shares. Figures for the B shares

3

�

In fairness, we’ve seen plenty of successes as well, some truly outstanding. There are many giant-

company managers whom I greatly admire; Ken Chenault of American Express, Jeff Immelt of G.E. and

Dick Kovacevich of Wells Fargo come quickly to mind. But I don’t think I could do the management job

they do. And I know I wouldn’t enjoy many of the duties that come with their positions – meetings,

speeches, foreign travel, the charity circuit and governmental relations. For me, Ronald Reagan had it

right: “It’s probably true that hard work never killed anyone – but why take the chance?”

So I’ve taken the easy route, just sitting back and working through great managers who run their

own shows. My only tasks are to cheer them on, sculpt and harden our corporate culture, and make major

capital-allocation decisions. Our managers have returned this trust by working hard and effectively.

For their performance over the last 42 years – and particularly for 2006 – Charlie and I thank

them.

Yardsticks

Charlie and I measure Berkshire’s progress and evaluate its intrinsic value in a number of ways.

No single criterion is effective in doing these jobs, and even an avalanche of statistics will not capture some

factors that are important. For example, it’s essential that we have managers much younger than I available

to succeed me. Berkshire has never been in better shape in this regard – but I can’t prove it to you with

numbers.

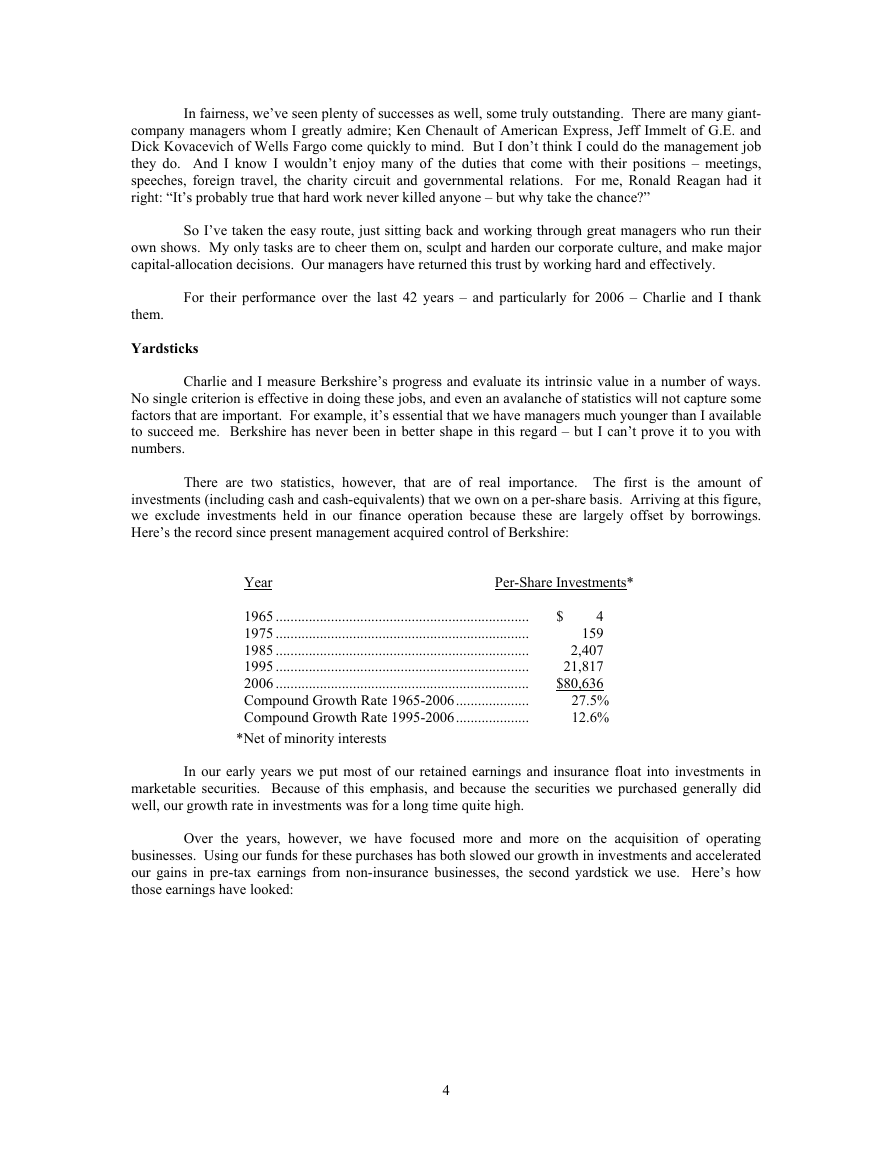

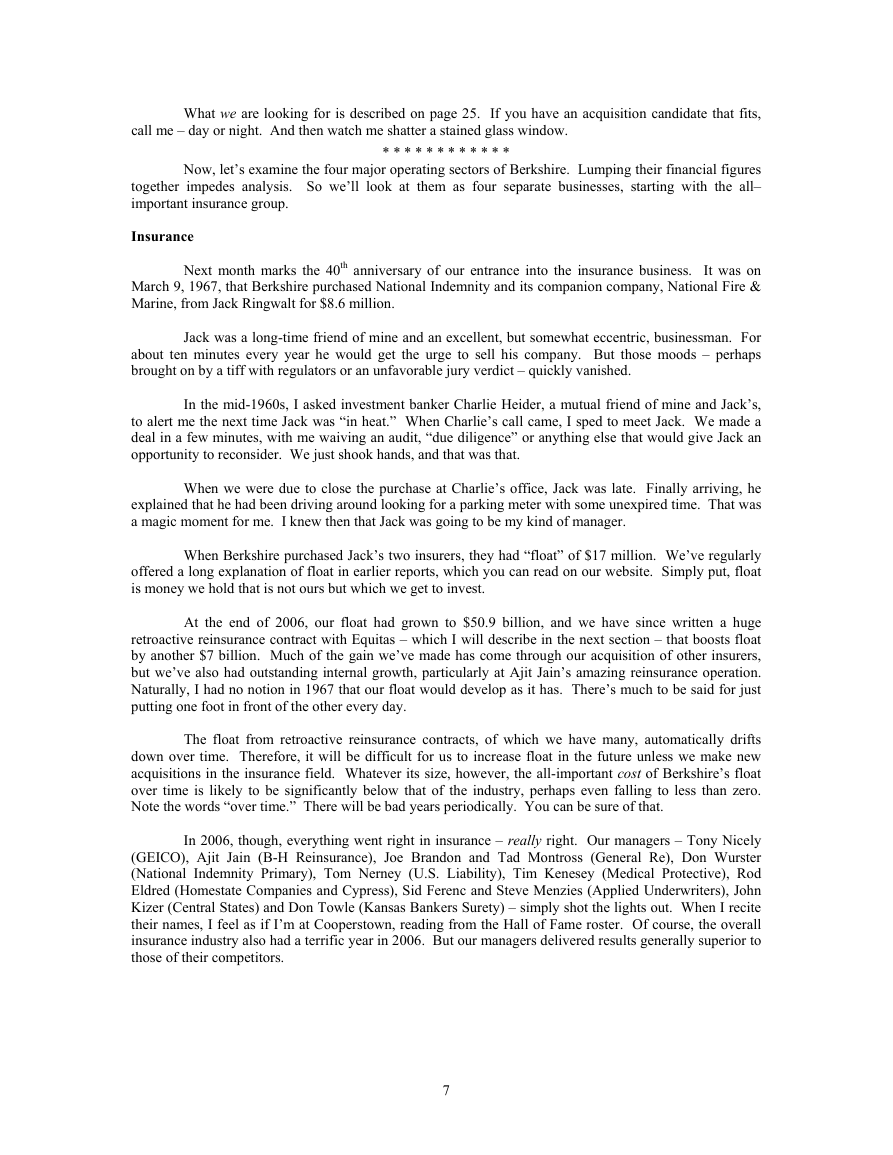

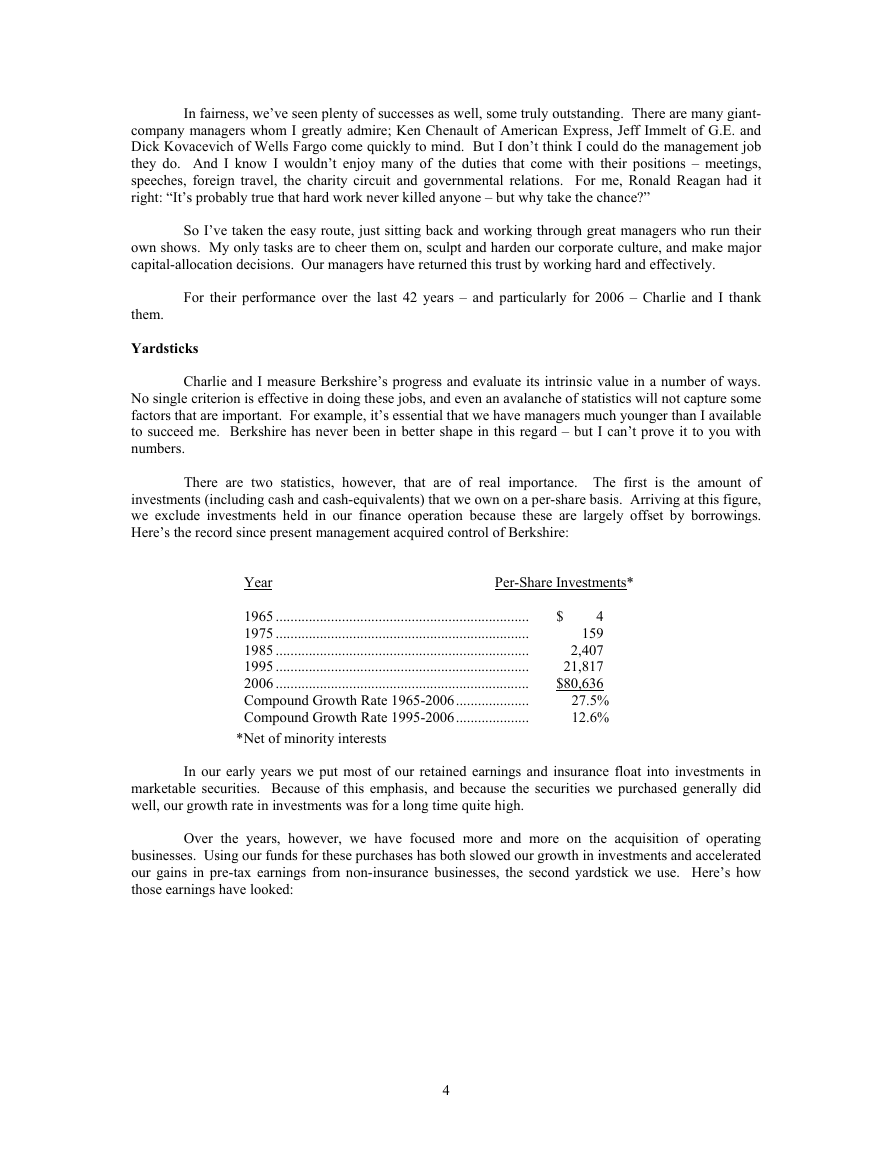

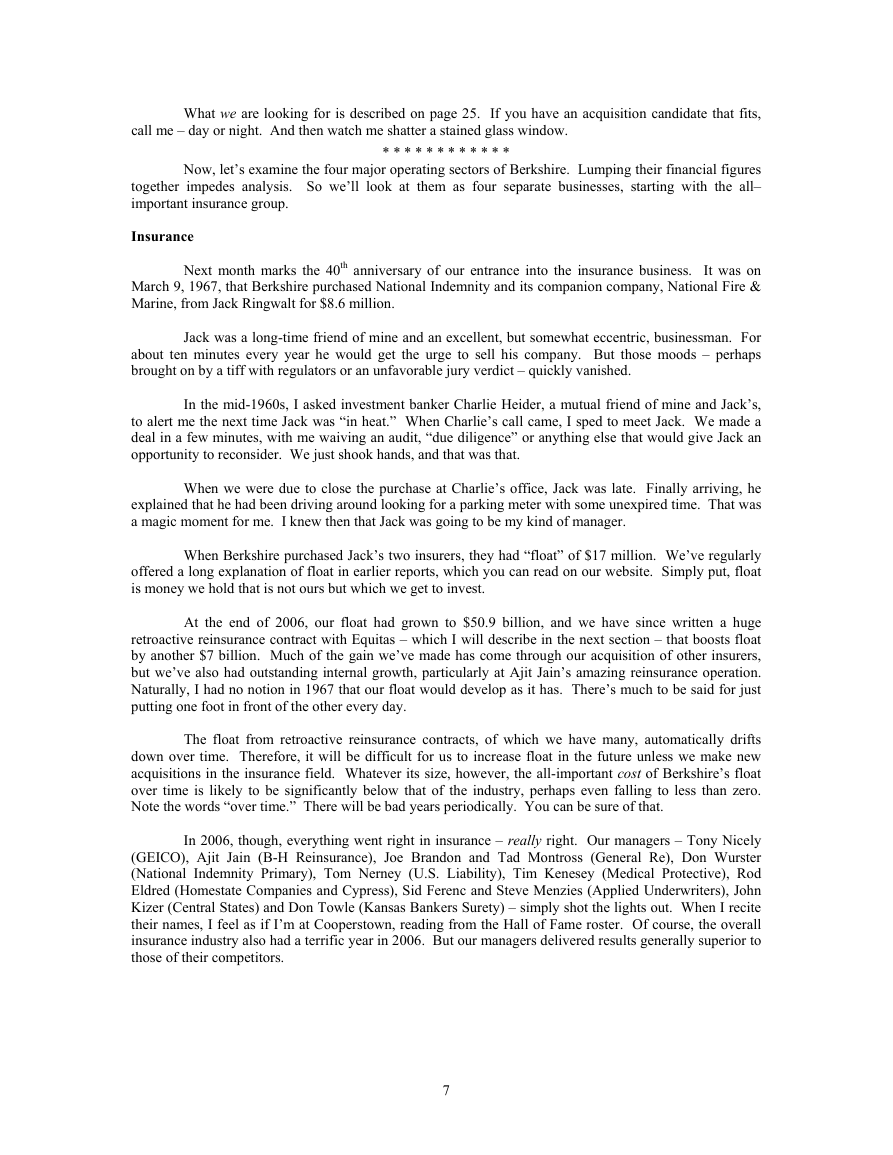

There are two statistics, however, that are of real importance. The first is the amount of

investments (including cash and cash-equivalents) that we own on a per-share basis. Arriving at this figure,

we exclude investments held in our finance operation because these are largely offset by borrowings.

Here’s the record since present management acquired control of Berkshire:

Per-Share Investments*

Year

1965 .....................................................................

1975 .....................................................................

1985 .....................................................................

1995 .....................................................................

2006 .....................................................................

Compound Growth Rate 1965-2006....................

Compound Growth Rate 1995-2006....................

*Net of minority interests

$ 4

159

2,407

21,817

$80,636

27.5%

12.6%

In our early years we put most of our retained earnings and insurance float into investments in

marketable securities. Because of this emphasis, and because the securities we purchased generally did

well, our growth rate in investments was for a long time quite high.

Over the years, however, we have focused more and more on the acquisition of operating

businesses. Using our funds for these purchases has both slowed our growth in investments and accelerated

our gains in pre-tax earnings from non-insurance businesses, the second yardstick we use. Here’s how

those earnings have looked:

4

�

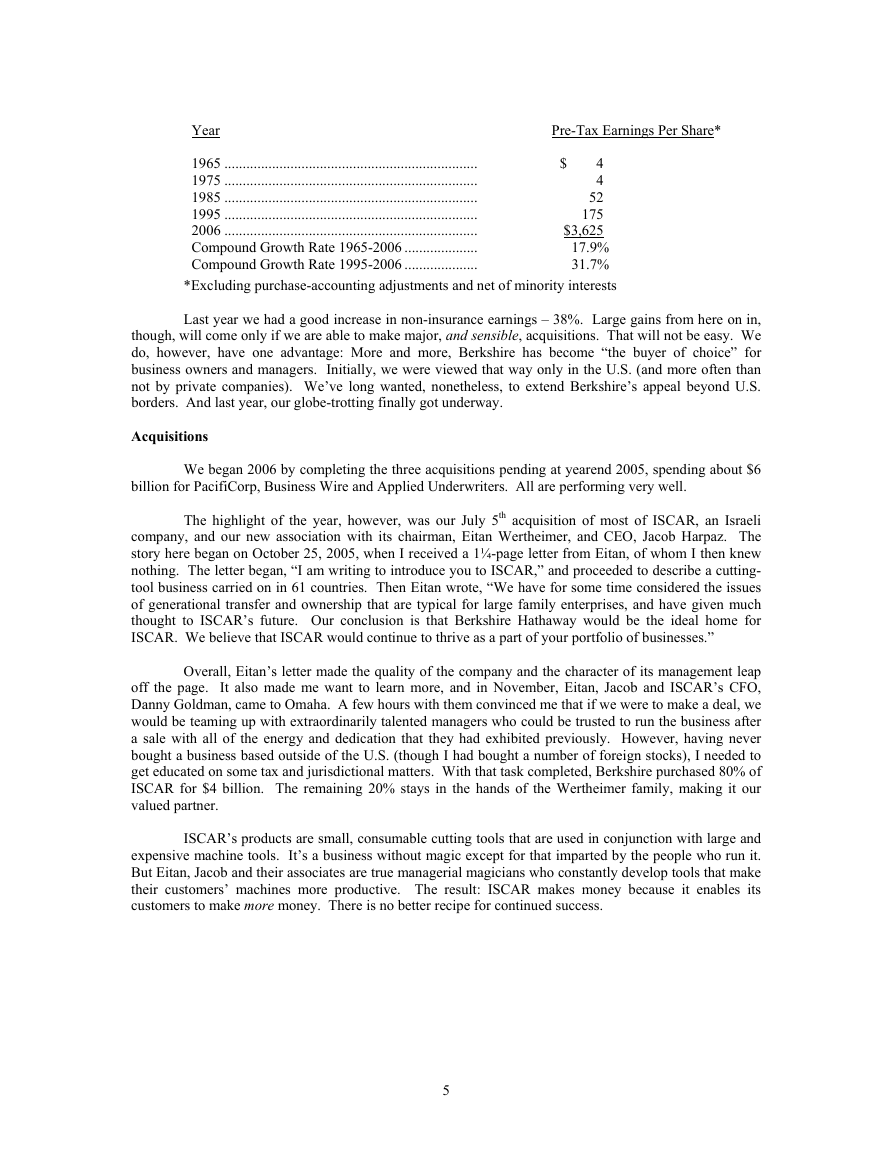

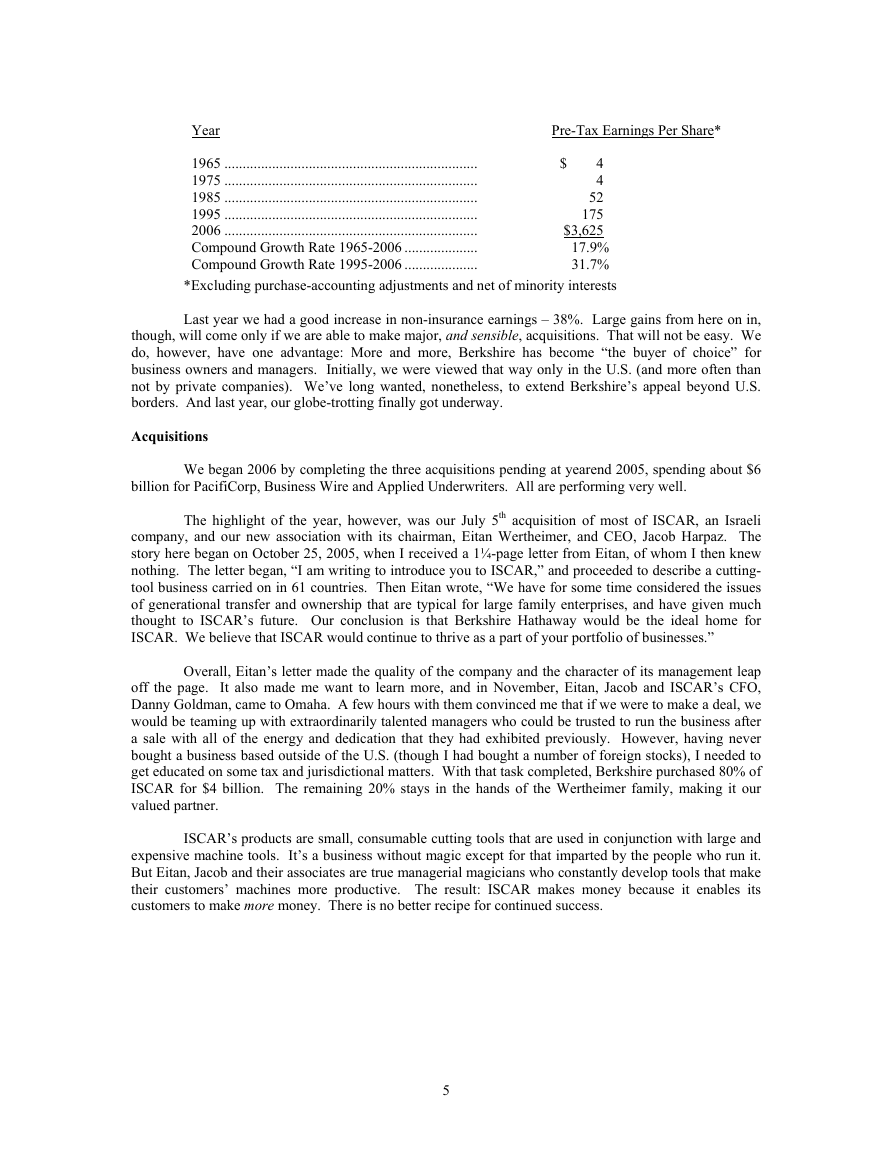

Pre-Tax Earnings Per Share*

Year

1965 .....................................................................

$ 4

1975 .....................................................................

4

1985 .....................................................................

52

1995 .....................................................................

175

2006 .....................................................................

$3,625

Compound Growth Rate 1965-2006 ....................

17.9%

Compound Growth Rate 1995-2006 ....................

31.7%

*Excluding purchase-accounting adjustments and net of minority interests

Last year we had a good increase in non-insurance earnings – 38%. Large gains from here on in,

though, will come only if we are able to make major, and sensible, acquisitions. That will not be easy. We

do, however, have one advantage: More and more, Berkshire has become “the buyer of choice” for

business owners and managers. Initially, we were viewed that way only in the U.S. (and more often than

not by private companies). We’ve long wanted, nonetheless, to extend Berkshire’s appeal beyond U.S.

borders. And last year, our globe-trotting finally got underway.

Acquisitions

billion for PacifiCorp, Business Wire and Applied Underwriters. All are performing very well.

The highlight of the year, however, was our July 5th acquisition of most of ISCAR, an Israeli

company, and our new association with its chairman, Eitan Wertheimer, and CEO, Jacob Harpaz. The

story here began on October 25, 2005, when I received a 1¼-page letter from Eitan, of whom I then knew

nothing. The letter began, “I am writing to introduce you to ISCAR,” and proceeded to describe a cutting-

tool business carried on in 61 countries. Then Eitan wrote, “We have for some time considered the issues

of generational transfer and ownership that are typical for large family enterprises, and have given much

thought to ISCAR’s future. Our conclusion is that Berkshire Hathaway would be the ideal home for

ISCAR. We believe that ISCAR would continue to thrive as a part of your portfolio of businesses.”

We began 2006 by completing the three acquisitions pending at yearend 2005, spending about $6

Overall, Eitan’s letter made the quality of the company and the character of its management leap

off the page. It also made me want to learn more, and in November, Eitan, Jacob and ISCAR’s CFO,

Danny Goldman, came to Omaha. A few hours with them convinced me that if we were to make a deal, we

would be teaming up with extraordinarily talented managers who could be trusted to run the business after

a sale with all of the energy and dedication that they had exhibited previously. However, having never

bought a business based outside of the U.S. (though I had bought a number of foreign stocks), I needed to

get educated on some tax and jurisdictional matters. With that task completed, Berkshire purchased 80% of

ISCAR for $4 billion. The remaining 20% stays in the hands of the Wertheimer family, making it our

valued partner.

ISCAR’s products are small, consumable cutting tools that are used in conjunction with large and

expensive machine tools. It’s a business without magic except for that imparted by the people who run it.

But Eitan, Jacob and their associates are true managerial magicians who constantly develop tools that make

their customers’ machines more productive. The result: ISCAR makes money because it enables its

customers to make more money. There is no better recipe for continued success.

5

�

In September, Charlie and I, along with five Berkshire associates, visited ISCAR in Israel. We –

and I mean every one of us – have never been more impressed with any operation. At ISCAR, as

throughout Israel, brains and energy are ubiquitous. Berkshire shareholders are lucky to have joined with

Eitan, Jacob, Danny and their talented associates.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

A few months later, Berkshire again became “the buyer of choice” in a deal brought to us by my

friend, John Roach, of Fort Worth. John, many of you will remember, was Chairman of Justin Industries,

which we bought in 2000. At that time John was helping John Justin, who was terminally ill, find a

permanent home for his company. John Justin died soon after we bought Justin Industries, but it has since

been run exactly as we promised him it would be.

Visiting me in November, John Roach brought along Paul Andrews, Jr., owner of about 80% of

TTI, a Fort Worth distributor of electronic components. Over a 35-year period, Paul built TTI from

$112,000 of sales to $1.3 billion. He is a remarkable entrepreneur and operator.

Paul, 64, loves running his business. But not long ago he happened to witness how disruptive the

death of a founder can be both to a private company’s employees and the owner’s family. What starts out

as disruptive, furthermore, often evolves into destructive. About a year ago, therefore, Paul began to think

about selling TTI. His goal was to put his business in the hands of an owner he had carefully chosen, rather

than allowing a trust officer or lawyer to conduct an auction after his death.

Paul rejected the idea of a “strategic” buyer, knowing that in the pursuit of “synergies,” an owner

of that type would be apt to dismantle what he had so carefully built, a move that would uproot hundreds of

his associates (and perhaps wound TTI’s business in the process). He also ruled out a private equity firm,

which would very likely load the company with debt and then flip it as soon as possible.

That left Berkshire. Paul and I met on the morning of November 15th and made a deal before

lunch. Later he wrote me: “After our meeting, I am confident that Berkshire is the right owner for TTI . . .

I am proud of our past and excited about our future.” And so are Charlie and I.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

We also made some “tuck-in” acquisitions during 2006 at Fruit of the Loom (“Fruit”), MiTek,

CTB, Shaw and Clayton. Fruit made the largest purchases. First, it bought Russell Corp., a leading

producer of athletic apparel and uniforms for about $1.2 billion (including assumed debt) and in December

it agreed to buy the intimate apparel business of VF Corp. Together, these acquisitions add about $2.2

billion to Fruit’s sales and bring with them about 23,000 employees.

Charlie and I love it when we can acquire businesses that can be placed under managers, such as

John Holland at Fruit, who have already shown their stuff at Berkshire. MiTek, for example, has made 14

acquisitions since we purchased it in 2001, and Gene Toombs has delivered results from these deals far in

excess of what he had predicted. In effect, we leverage the managerial talent already with us by these tuck-

in deals. We will make many more.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

We continue, however, to need “elephants” in order for us to use Berkshire’s flood of incoming

cash. Charlie and I must therefore ignore the pursuit of mice and focus our acquisition efforts on much

bigger game.

Our exemplar is the older man who crashed his grocery cart into that of a much younger fellow

while both were shopping. The elderly man explained apologetically that he had lost track of his wife and

was preoccupied searching for her. His new acquaintance said that by coincidence his wife had also

wandered off and suggested that it might be more efficient if they jointly looked for the two women.

Agreeing, the older man asked his new companion what his wife looked like. “She’s a gorgeous blonde,”

the fellow answered, “with a body that would cause a bishop to go through a stained glass window, and

she’s wearing tight white shorts. How about yours?” The senior citizen wasted no words: “Forget her,

we’ll look for yours.”

6

�

What we are looking for is described on page 25. If you have an acquisition candidate that fits,

call me – day or night. And then watch me shatter a stained glass window.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Now, let’s examine the four major operating sectors of Berkshire. Lumping their financial figures

together impedes analysis. So we’ll look at them as four separate businesses, starting with the all–

important insurance group.

Insurance

Next month marks the 40th anniversary of our entrance into the insurance business. It was on

March 9, 1967, that Berkshire purchased National Indemnity and its companion company, National Fire &

Marine, from Jack Ringwalt for $8.6 million.

Jack was a long-time friend of mine and an excellent, but somewhat eccentric, businessman. For

about ten minutes every year he would get the urge to sell his company. But those moods – perhaps

brought on by a tiff with regulators or an unfavorable jury verdict – quickly vanished.

In the mid-1960s, I asked investment banker Charlie Heider, a mutual friend of mine and Jack’s,

to alert me the next time Jack was “in heat.” When Charlie’s call came, I sped to meet Jack. We made a

deal in a few minutes, with me waiving an audit, “due diligence” or anything else that would give Jack an

opportunity to reconsider. We just shook hands, and that was that.

When we were due to close the purchase at Charlie’s office, Jack was late. Finally arriving, he

explained that he had been driving around looking for a parking meter with some unexpired time. That was

a magic moment for me. I knew then that Jack was going to be my kind of manager.

When Berkshire purchased Jack’s two insurers, they had “float” of $17 million. We’ve regularly

offered a long explanation of float in earlier reports, which you can read on our website. Simply put, float

is money we hold that is not ours but which we get to invest.

At the end of 2006, our float had grown to $50.9 billion, and we have since written a huge

retroactive reinsurance contract with Equitas – which I will describe in the next section – that boosts float

by another $7 billion. Much of the gain we’ve made has come through our acquisition of other insurers,

but we’ve also had outstanding internal growth, particularly at Ajit Jain’s amazing reinsurance operation.

Naturally, I had no notion in 1967 that our float would develop as it has. There’s much to be said for just

putting one foot in front of the other every day.

The float from retroactive reinsurance contracts, of which we have many, automatically drifts

down over time. Therefore, it will be difficult for us to increase float in the future unless we make new

acquisitions in the insurance field. Whatever its size, however, the all-important cost of Berkshire’s float

over time is likely to be significantly below that of the industry, perhaps even falling to less than zero.

Note the words “over time.” There will be bad years periodically. You can be sure of that.

In 2006, though, everything went right in insurance – really right. Our managers – Tony Nicely

(GEICO), Ajit Jain (B-H Reinsurance), Joe Brandon and Tad Montross (General Re), Don Wurster

(National Indemnity Primary), Tom Nerney (U.S. Liability), Tim Kenesey (Medical Protective), Rod

Eldred (Homestate Companies and Cypress), Sid Ferenc and Steve Menzies (Applied Underwriters), John

Kizer (Central States) and Don Towle (Kansas Bankers Surety) – simply shot the lights out. When I recite

their names, I feel as if I’m at Cooperstown, reading from the Hall of Fame roster. Of course, the overall

insurance industry also had a terrific year in 2006. But our managers delivered results generally superior to

those of their competitors.

7

�

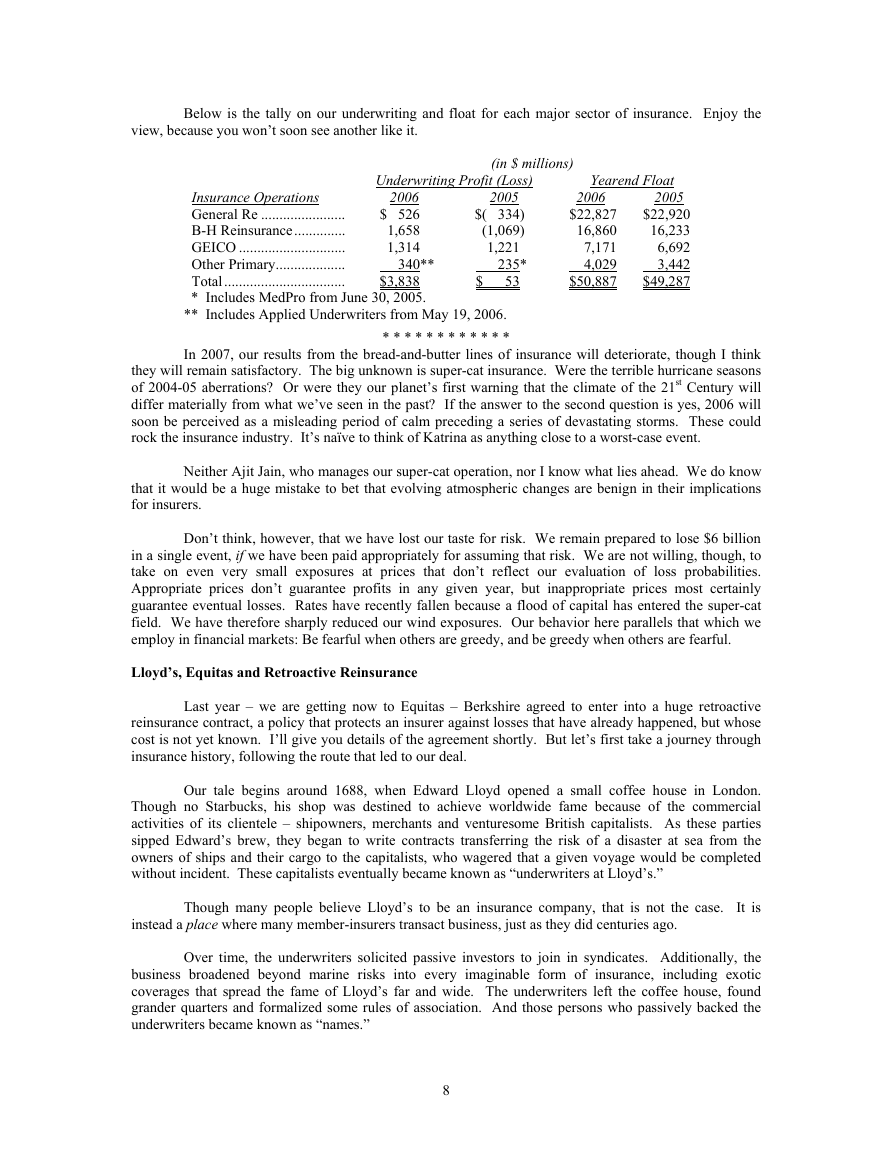

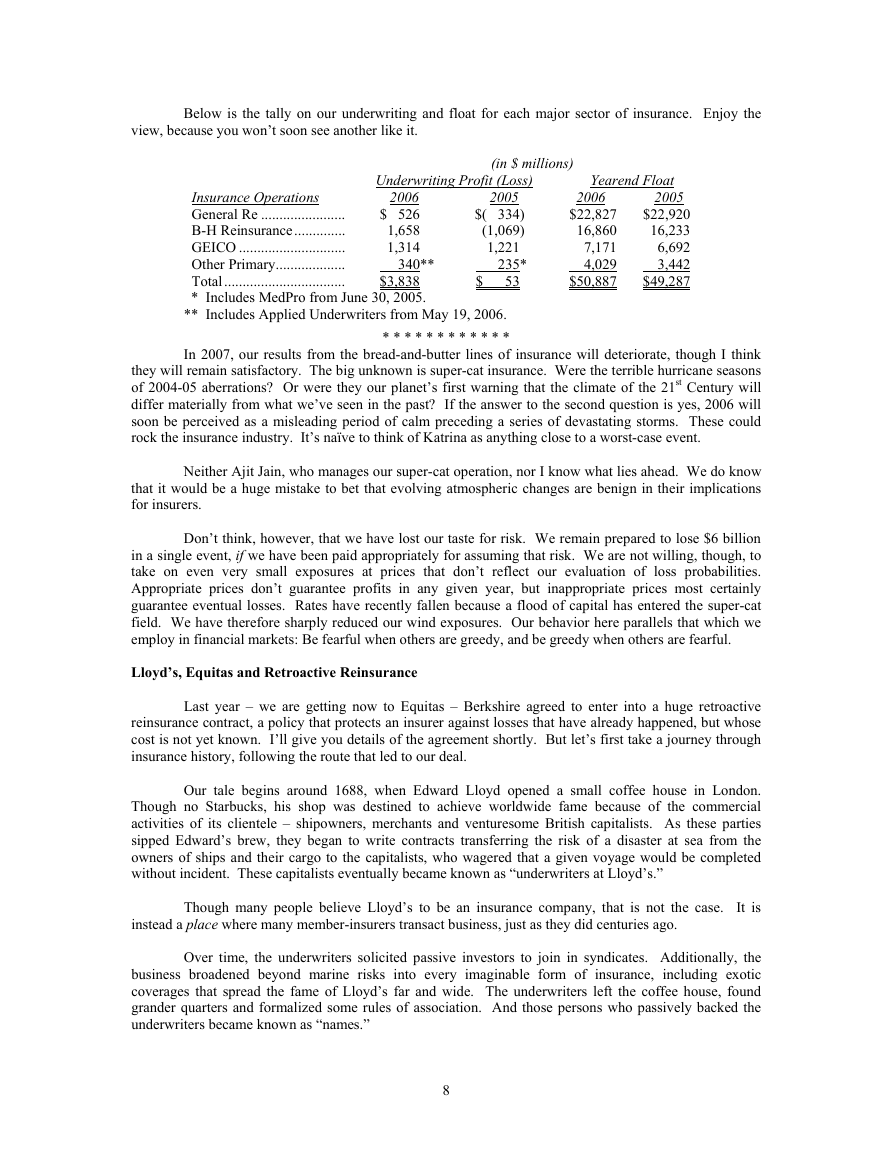

(in $ millions)

Underwriting Profit (Loss)

2005

2006

Insurance Operations

$ 526

General Re .......................

1,658

B-H Reinsurance..............

1,314

GEICO .............................

Other Primary...................

340**

Total.................................

$3,838

* Includes MedPro from June 30, 2005.

** Includes Applied Underwriters from May 19, 2006.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

$( 334)

(1,069)

1,221

235*

$ 53

Yearend Float

2005

2006

$22,827

16,860

7,171

4,029

$50,887

$22,920

16,233

6,692

3,442

$49,287

Below is the tally on our underwriting and float for each major sector of insurance. Enjoy the

view, because you won’t soon see another like it.

In 2007, our results from the bread-and-butter lines of insurance will deteriorate, though I think

they will remain satisfactory. The big unknown is super-cat insurance. Were the terrible hurricane seasons

of 2004-05 aberrations? Or were they our planet’s first warning that the climate of the 21st Century will

differ materially from what we’ve seen in the past? If the answer to the second question is yes, 2006 will

soon be perceived as a misleading period of calm preceding a series of devastating storms. These could

rock the insurance industry. It’s naïve to think of Katrina as anything close to a worst-case event.

Neither Ajit Jain, who manages our super-cat operation, nor I know what lies ahead. We do know

that it would be a huge mistake to bet that evolving atmospheric changes are benign in their implications

for insurers.

Don’t think, however, that we have lost our taste for risk. We remain prepared to lose $6 billion

in a single event, if we have been paid appropriately for assuming that risk. We are not willing, though, to

take on even very small exposures at prices that don’t reflect our evaluation of loss probabilities.

Appropriate prices don’t guarantee profits in any given year, but inappropriate prices most certainly

guarantee eventual losses. Rates have recently fallen because a flood of capital has entered the super-cat

field. We have therefore sharply reduced our wind exposures. Our behavior here parallels that which we

employ in financial markets: Be fearful when others are greedy, and be greedy when others are fearful.

Lloyd’s, Equitas and Retroactive Reinsurance

Last year – we are getting now to Equitas – Berkshire agreed to enter into a huge retroactive

reinsurance contract, a policy that protects an insurer against losses that have already happened, but whose

cost is not yet known. I’ll give you details of the agreement shortly. But let’s first take a journey through

insurance history, following the route that led to our deal.

Our tale begins around 1688, when Edward Lloyd opened a small coffee house in London.

Though no Starbucks, his shop was destined to achieve worldwide fame because of the commercial

activities of its clientele – shipowners, merchants and venturesome British capitalists. As these parties

sipped Edward’s brew, they began to write contracts transferring the risk of a disaster at sea from the

owners of ships and their cargo to the capitalists, who wagered that a given voyage would be completed

without incident. These capitalists eventually became known as “underwriters at Lloyd’s.”

instead a place where many member-insurers transact business, just as they did centuries ago.

Over time, the underwriters solicited passive investors to join in syndicates. Additionally, the

business broadened beyond marine risks into every imaginable form of insurance, including exotic

coverages that spread the fame of Lloyd’s far and wide. The underwriters left the coffee house, found

grander quarters and formalized some rules of association. And those persons who passively backed the

underwriters became known as “names.”

Though many people believe Lloyd’s to be an insurance company, that is not the case. It is

8

�

Eventually, the names came to include many thousands of people from around the world, who

joined expecting to pick up some extra change without effort or serious risk. True, prospective names were

always solemnly told that they would have unlimited and everlasting liability for the consequences of their

syndicate’s underwriting – “down to the last cufflink,” as the quaint description went. But that warning

came to be viewed as perfunctory. Three hundred years of retained cufflinks acted as a powerful sedative

to the names poised to sign up.

Then came asbestos. When its prospective costs were added to the tidal wave of environmental

and product claims that surfaced in the 1980s, Lloyd’s began to implode. Policies written decades earlier –

and largely forgotten about – were developing huge losses. No one could intelligently estimate their total,

but it was certain to be many tens of billions of dollars. The specter of unending and unlimited losses

terrified existing names and scared away prospects. Many names opted for bankruptcy; some even chose

suicide.

From these shambles, there came a desperate effort to resuscitate Lloyd’s. In 1996, the powers

that be at the institution allotted £11.1 billion to a new company, Equitas, and made it responsible for

paying all claims on policies written before 1993. In effect, this plan pooled the misery of the many

syndicates in trouble. Of course, the money allotted could prove to be insufficient – and if that happened,

the names remained liable for the shortfall.

But the new plan, by concentrating all of the liabilities in one place, had the advantage of

eliminating much of the costly intramural squabbling that went on among syndicates. Moreover, the

pooling allowed claims evaluation, negotiation and litigation to be handled more intelligently than had been

the case previously. Equitas embraced Ben Franklin’s thinking: “We must all hang together, or assuredly

we shall hang separately.”

From the start, many people predicted Equitas would eventually fail. But as Ajit and I reviewed

the facts in the spring of 2006 – 13 years after the last exposed policy had been written and after the

payment of £11.3 billion in claims – we concluded that the patient was likely to survive. And so we

decided to offer a huge reinsurance policy to Equitas.

Because plenty of imponderables continue to exist, Berkshire could not provide Equitas, and its

27,972 names, unlimited protection. But we said – and I’m simplifying – that if Equitas would give us

$7.12 billion in cash and securities (this is the float I spoke about), we would pay all of its future claims and

expenses up to $13.9 billion. That amount was $5.7 billion above what Equitas had recently guessed its

ultimate liabilities to be. Thus the names received a huge – and almost certainly sufficient – amount of

future protection against unpleasant surprises. Indeed the protection is so large that Equitas plans a cash

payment to its thousands of names, an event few of them had ever dreamed possible.

And how will Berkshire fare? That depends on how much “known” claims will end up costing us,

how many yet-to-be-presented claims will surface and what they will cost, how soon claim payments will

be made and how much we earn on the cash we receive before it must be paid out. Ajit and I think the odds

are in our favor. And should we be wrong, Berkshire can handle it.

easy at night, and we think we’ve just bought them the world’s best mattress.”

Scott Moser, the CEO of Equitas, summarized the transaction neatly: “Names wanted to sleep

* * * * * * * * * * *

Warning: It’s time to eat your broccoli – I am now going to talk about accounting matters. I owe

this to those Berkshire shareholders who love reading about debits and credits. I hope both of you find this

discussion helpful. All others can skip this section; there will be no quiz.

Berkshire has done many retroactive transactions – in both number and amount a multiple of such

policies entered into by any other insurer. We are the reinsurer of choice for these coverages because the

obligations that are transferred to us – for example, lifetime indemnity and medical payments to be made to

injured workers – may not be fully satisfied for 50 years or more. No other company can offer the certainty

9

�