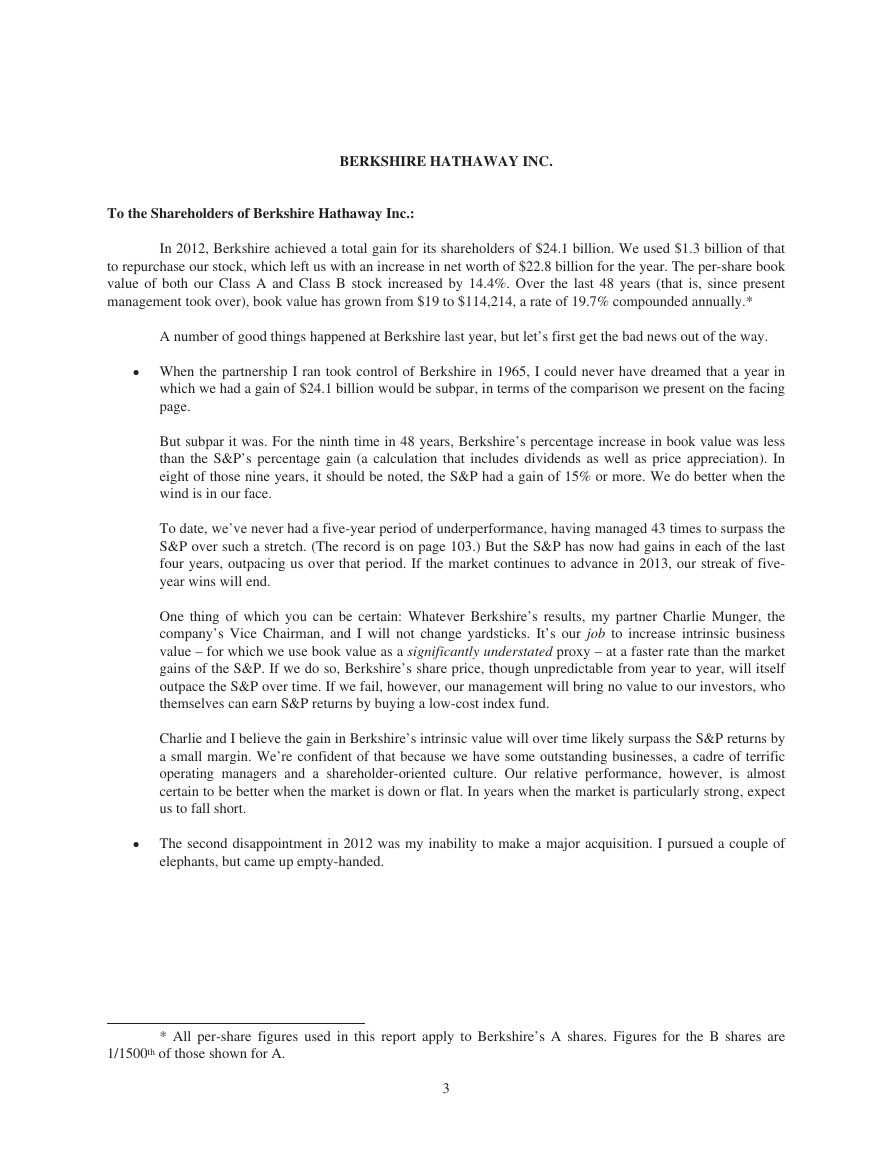

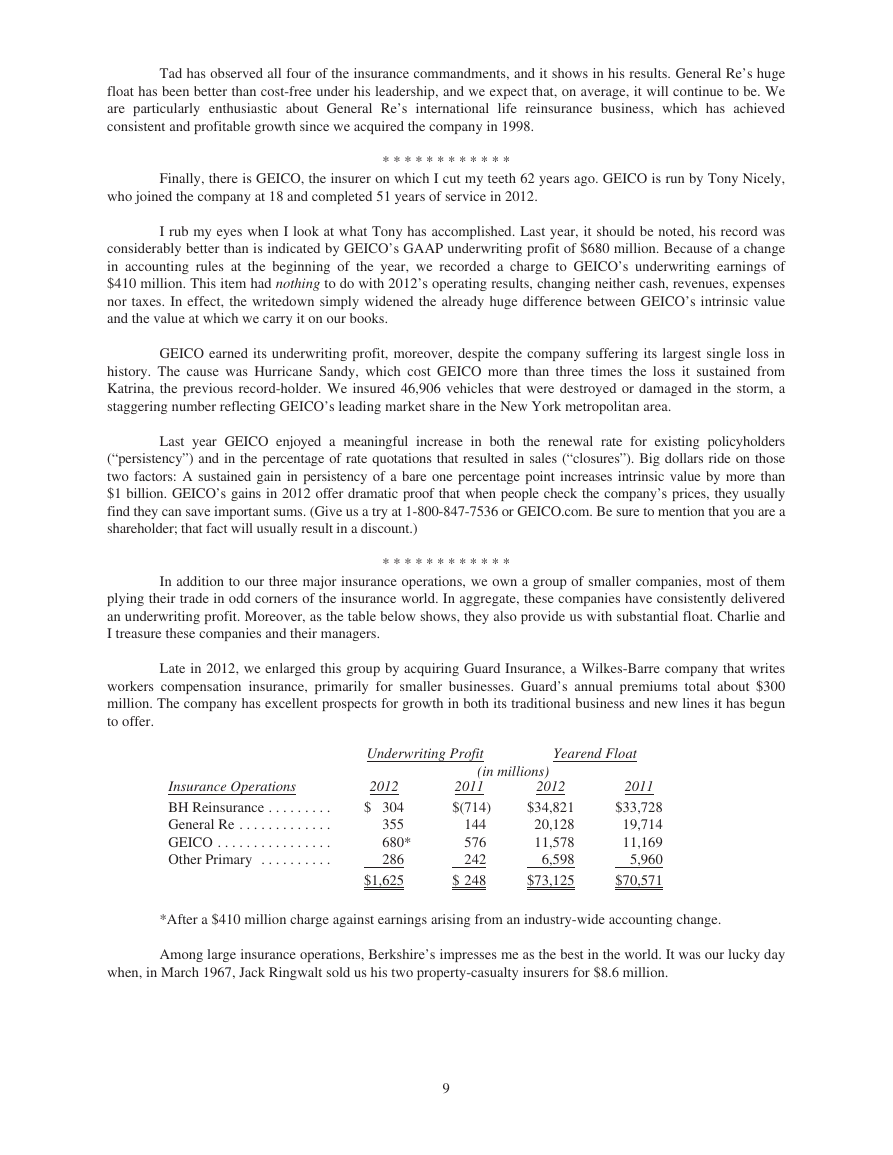

Berkshire’s Corporate Performance vs. the S&P 500

Annual Percentage Change

in S&P 500

in Per-Share

Book Value of

Berkshire

with Dividends

Included

(2)

10.0

(11.7)

30.9

11.0

(8.4)

3.9

14.6

18.9

(14.8)

(26.4)

37.2

23.6

(7.4)

6.4

18.2

32.3

(5.0)

21.4

22.4

6.1

31.6

18.6

5.1

16.6

31.7

(3.1)

30.5

7.6

10.1

1.3

37.6

23.0

33.4

28.6

21.0

(9.1)

(11.9)

(22.1)

28.7

10.9

4.9

15.8

5.5

(37.0)

26.5

15.1

2.1

16.0

Relative

Results

(1)-(2)

13.8

32.0

(19.9)

8.0

24.6

8.1

1.8

2.8

19.5

31.9

(15.3)

35.7

39.3

17.6

17.5

(13.0)

36.4

18.6

9.9

7.5

16.6

7.5

14.4

3.5

12.7

10.5

9.1

12.7

4.2

12.6

5.5

8.8

0.7

19.7

(20.5)

15.6

5.7

32.1

(7.7)

(0.4)

1.5

2.6

5.5

27.4

(6.7)

(2.1)

2.5

(1.6)

10.3

Year

1965 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1966 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1967 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1968 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1969 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1970 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1971 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1972 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1973 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1974 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1975 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1976 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1977 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1978 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1979 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1980 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1981 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1982 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1983 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1984 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1985 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1986 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1987 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1988 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1989 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1990 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1991 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1992 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1993 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1994 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1995 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1996 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1997 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1998 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1999 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2000 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2001 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2002 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2003 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2004 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2005 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2006 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2007 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2008 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2009 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2010 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2011 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2012 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

(1)

23.8

20.3

11.0

19.0

16.2

12.0

16.4

21.7

4.7

5.5

21.9

59.3

31.9

24.0

35.7

19.3

31.4

40.0

32.3

13.6

48.2

26.1

19.5

20.1

44.4

7.4

39.6

20.3

14.3

13.9

43.1

31.8

34.1

48.3

0.5

6.5

(6.2)

10.0

21.0

10.5

6.4

18.4

11.0

(9.6)

19.8

13.0

4.6

14.4

Compounded Annual Gain – 1965-2012 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Overall Gain – 1964-2012 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19.7%

586,817%

9.4%

7,433%

Notes: Data are for calendar years with these exceptions: 1965 and 1966, year ended 9/30; 1967, 15 months ended

12/31. Starting in 1979, accounting rules required insurance companies to value the equity securities they hold at

market rather than at the lower of cost or market, which was previously the requirement. In this table, Berkshire’s

results through 1978 have been restated to conform to the changed rules. In all other respects, the results are calculated

using the numbers originally reported. The S&P 500 numbers are pre-tax whereas the Berkshire numbers are after-

tax. If a corporation such as Berkshire were simply to have owned the S&P 500 and accrued the appropriate taxes, its

results would have lagged the S&P 500 in years when that index showed a positive return, but would have exceeded the

S&P 500 in years when the index showed a negative return. Over the years, the tax costs would have caused the

aggregate lag to be substantial.

2

�

BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC.

To the Shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:

In 2012, Berkshire achieved a total gain for its shareholders of $24.1 billion. We used $1.3 billion of that

to repurchase our stock, which left us with an increase in net worth of $22.8 billion for the year. The per-share book

value of both our Class A and Class B stock increased by 14.4%. Over the last 48 years (that is, since present

management took over), book value has grown from $19 to $114,214, a rate of 19.7% compounded annually.*

A number of good things happened at Berkshire last year, but let’s first get the bad news out of the way.

Š When the partnership I ran took control of Berkshire in 1965, I could never have dreamed that a year in

which we had a gain of $24.1 billion would be subpar, in terms of the comparison we present on the facing

page.

But subpar it was. For the ninth time in 48 years, Berkshire’s percentage increase in book value was less

than the S&P’s percentage gain (a calculation that includes dividends as well as price appreciation). In

eight of those nine years, it should be noted, the S&P had a gain of 15% or more. We do better when the

wind is in our face.

To date, we’ve never had a five-year period of underperformance, having managed 43 times to surpass the

S&P over such a stretch. (The record is on page 103.) But the S&P has now had gains in each of the last

four years, outpacing us over that period. If the market continues to advance in 2013, our streak of five-

year wins will end.

One thing of which you can be certain: Whatever Berkshire’s results, my partner Charlie Munger, the

company’s Vice Chairman, and I will not change yardsticks. It’s our job to increase intrinsic business

value – for which we use book value as a significantly understated proxy – at a faster rate than the market

gains of the S&P. If we do so, Berkshire’s share price, though unpredictable from year to year, will itself

outpace the S&P over time. If we fail, however, our management will bring no value to our investors, who

themselves can earn S&P returns by buying a low-cost index fund.

Charlie and I believe the gain in Berkshire’s intrinsic value will over time likely surpass the S&P returns by

a small margin. We’re confident of that because we have some outstanding businesses, a cadre of terrific

operating managers and a shareholder-oriented culture. Our relative performance, however, is almost

certain to be better when the market is down or flat. In years when the market is particularly strong, expect

us to fall short.

Š

The second disappointment in 2012 was my inability to make a major acquisition. I pursued a couple of

elephants, but came up empty-handed.

* All per-share figures used in this report apply to Berkshire’s A shares. Figures for the B shares are

1/1500th of those shown for A.

3

�

Our luck, however, changed early this year. In February, we agreed to buy 50% of a holding company that

will own all of H. J. Heinz. The other half will be owned by a small group of investors led by Jorge Paulo

Lemann, a renowned Brazilian businessman and philanthropist.

We couldn’t be in better company. Jorge Paulo is a long-time friend of mine and an extraordinary

manager. His group and Berkshire will each contribute about $4 billion for common equity in the holding

company. Berkshire will also invest $8 billion in preferred shares that pay a 9% dividend. The preferred

has two other features that materially increase its value: at some point it will be redeemed at a significant

premium price and the preferred also comes with warrants permitting us to buy 5% of the holding

company’s common stock for a nominal sum.

Our total investment of about $12 billion soaks up much of what Berkshire earned last year. But we still

have plenty of cash and are generating more at a good clip. So it’s back to work; Charlie and I have again

donned our safari outfits and resumed our search for elephants.

Now to some good news from 2012:

Š

Last year I told you that BNSF, Iscar, Lubrizol, Marmon Group and MidAmerican Energy – our five most

profitable non-insurance companies – were likely to earn more than $10 billion pre-tax in 2012. They

delivered. Despite tepid U.S. growth and weakening economies throughout much of the world, our

“powerhouse five” had aggregate earnings of $10.1 billion, about $600 million more than in 2011.

Of this group, only MidAmerican, then earning $393 million pre-tax, was owned by Berkshire eight years

ago. Subsequently, we purchased another three of the five on an all-cash basis. In acquiring the fifth,

BNSF, we paid about 70% of the cost in cash, and for the remainder, issued shares that increased the

amount outstanding by 6.1%. Consequently, the $9.7 billion gain in annual earnings delivered Berkshire

by the five companies has been accompanied by only minor dilution. That satisfies our goal of not simply

growing, but rather increasing per-share results.

Unless the U.S. economy tanks – which we don’t expect – our powerhouse five should again deliver higher

earnings in 2013. The five outstanding CEOs who run them will see to that.

Š

Though I failed to land a major acquisition in 2012, the managers of our subsidiaries did far better. We had

a record year for “bolt-on” purchases, spending about $2.3 billion for 26 companies that were melded into

our existing businesses. These transactions were completed without Berkshire issuing any shares.

Charlie and I love these acquisitions: Usually they are low-risk, burden headquarters not at all, and expand

the scope of our proven managers.

Š Our insurance operations shot the lights out last year. While giving Berkshire $73 billion of free money to

invest, they also delivered a $1.6 billion underwriting gain, the tenth consecutive year of profitable

underwriting. This is truly having your cake and eating it too.

GEICO led the way, continuing to gobble up market share without sacrificing underwriting discipline.

Since 1995, when we obtained control, GEICO’s share of the personal-auto market has grown from 2.5% to

9.7%. Premium volume meanwhile increased from $2.8 billion to $16.7 billion. Much more growth lies

ahead.

The credit for GEICO’s extraordinary performance goes to Tony Nicely and his 27,000 associates. And to

that cast, we should add our Gecko. Neither rain nor storm nor gloom of night can stop him; the little lizard

just soldiers on, telling Americans how they can save big money by going to GEICO.com.

When I count my blessings, I count GEICO twice.

4

�

Š

Š

Š

Š

Todd Combs and Ted Weschler, our new investment managers, have proved to be smart, models of

integrity, helpful to Berkshire in many ways beyond portfolio management, and a perfect cultural fit. We

hit the jackpot with these two. In 2012 each outperformed the S&P 500 by double-digit margins. They left me in

the dust as well.

Consequently, we have increased the funds managed by each to almost $5 billion (some of this emanating

from the pension funds of our subsidiaries). Todd and Ted are young and will be around to manage

Berkshire’s massive portfolio long after Charlie and I have left the scene. You can rest easy when they

take over.

Berkshire’s yearend employment totaled a record 288,462 (see page 106 for details), up 17,604 from last

year. Our headquarters crew, however, remained unchanged at 24. No sense going crazy.

Berkshire’s “Big Four” investments – American Express, Coca-Cola, IBM and Wells Fargo – all had good

years. Our ownership interest in each of these companies increased during the year. We purchased

additional shares of Wells Fargo (our ownership now is 8.7% versus 7.6% at yearend 2011) and IBM (6.0%

versus 5.5%). Meanwhile, stock repurchases at Coca-Cola and American Express raised our percentage

ownership. Our equity in Coca-Cola grew from 8.8% to 8.9% and our interest at American Express from

13.0% to 13.7%.

Berkshire’s ownership interest in all four companies is likely to increase in the future. Mae West had it

right: “Too much of a good thing can be wonderful.”

The four companies possess marvelous businesses and are run by managers who are both talented and

shareholder-oriented. At Berkshire we much prefer owning a non-controlling but substantial portion of a

wonderful business to owning 100% of a so-so business. Our flexibility in capital allocation gives us a

significant advantage over companies that limit themselves only to acquisitions they can operate.

Going by our yearend share count, our portion of the “Big Four’s” 2012 earnings amounted to $3.9 billion.

In the earnings we report to you, however, we include only the dividends we receive – about $1.1 billion.

But make no mistake: The $2.8 billion of earnings we do not report is every bit as valuable to us as what

we record.

The earnings that the four companies retain are often used for repurchases – which enhance our share of

future earnings – and also for funding business opportunities that are usually advantageous. Over time we

expect substantially greater earnings from these four investees. If we are correct, dividends to Berkshire

will increase and, even more important, so will our unrealized capital gains (which, for the four, totaled

$26.7 billion at yearend).

There was a lot of hand-wringing last year among CEOs who cried “uncertainty” when faced with capital-

allocation decisions (despite many of their businesses having enjoyed record levels of both earnings and

cash). At Berkshire, we didn’t share their fears, instead spending a record $9.8 billion on plant and

equipment in 2012, about 88% of it in the United States. That’s 19% more than we spent in 2011, our

previous high. Charlie and I love investing large sums in worthwhile projects, whatever the pundits are

saying. We instead heed the words from Gary Allan’s new country song, “Every Storm Runs Out of Rain.”

We will keep our foot to the floor and will almost certainly set still another record for capital expenditures

in 2013. Opportunities abound in America.

A thought for my fellow CEOs: Of course, the immediate future is uncertain; America has faced the

unknown since 1776. It’s just that sometimes people focus on the myriad of uncertainties that always exist

while at other times they ignore them (usually because the recent past has been uneventful).

* * * * * * * * * * * *

5

�

American business will do fine over time. And stocks will do well just as certainly, since their fate is tied

to business performance. Periodic setbacks will occur, yes, but investors and managers are in a game that

is heavily stacked in their favor. (The Dow Jones Industrials advanced from 66 to 11,497 in the 20th

Century, a staggering 17,320% increase that materialized despite four costly wars, a Great Depression and

many recessions. And don’t forget that shareholders received substantial dividends throughout the century

as well.)

Since the basic game is so favorable, Charlie and I believe it’s a terrible mistake to try to dance in and out

of it based upon the turn of tarot cards, the predictions of “experts,” or the ebb and flow of business

activity. The risks of being out of the game are huge compared to the risks of being in it.

My own history provides a dramatic example: I made my first stock purchase in the spring of 1942 when

the U.S. was suffering major losses throughout the Pacific war zone. Each day’s headlines told of more

setbacks. Even so, there was no talk about uncertainty; every American I knew believed we would prevail.

The country’s success since that perilous time boggles the mind: On an inflation-adjusted basis, GDP per

capita more than quadrupled between 1941 and 2012. Throughout that period, every tomorrow has been

uncertain. America’s destiny, however, has always been clear: ever-increasing abundance.

If you are a CEO who has some large, profitable project you are shelving because of short-term worries,

call Berkshire. Let us unburden you.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

In summary, Charlie and I hope to build per-share intrinsic value by (1) improving the earning power of our

many subsidiaries; (2) further increasing their earnings through bolt-on acquisitions; (3) participating in the growth

of our investees; (4) repurchasing Berkshire shares when they are available at a meaningful discount from intrinsic

value; and (5) making an occasional large acquisition. We will also try to maximize results for you by rarely, if

ever, issuing Berkshire shares.

Those building blocks rest on a rock-solid foundation. A century hence, BNSF and MidAmerican Energy

will continue to play major roles in the American economy. Insurance, moreover, will always be essential for both

businesses and individuals – and no company brings greater resources to that arena than Berkshire. As we view

these and other strengths, Charlie and I like your company’s prospects.

Intrinsic Business Value

As much as Charlie and I talk about intrinsic business value, we cannot tell you precisely what that number

is for Berkshire shares (or, for that matter, any other stock). In our 2010 annual report, however, we laid out the

three elements – one of which was qualitative – that we believe are the keys to a sensible estimate of Berkshire’s

intrinsic value. That discussion is reproduced in full on pages 104-105.

Here is an update of the two quantitative factors: In 2012 our per-share investments increased 15.7% to

$113,786, and our per-share pre-tax earnings from businesses other than insurance and investments also increased

15.7% to $8,085.

Since 1970, our per-share investments have increased at a rate of 19.4% compounded annually, and our

per-share earnings figure has grown at a 20.8% clip. It is no coincidence that the price of Berkshire stock over the

42-year period has increased at a rate very similar to that of our two measures of value. Charlie and I like to see

gains in both areas, but our strong emphasis will always be on building operating earnings.

Now, let’s examine the four major sectors of our operations. Each has vastly different balance sheet and

income characteristics from the others. Lumping them together therefore impedes analysis. So we’ll present them

as four separate businesses, which is how Charlie and I view them.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

6

�

Insurance

Let’s look first at insurance, Berkshire’s core operation and the engine that has propelled our expansion

over the years.

Property-casualty (“P/C”) insurers receive premiums upfront and pay claims later. In extreme cases, such

as those arising from certain workers’ compensation accidents, payments can stretch over decades. This collect-

now, pay-later model leaves us holding large sums – money we call “float” – that will eventually go to others.

Meanwhile, we get to invest this float for Berkshire’s benefit. Though individual policies and claims come and go,

the amount of float we hold remains quite stable in relation to premium volume. Consequently, as our business

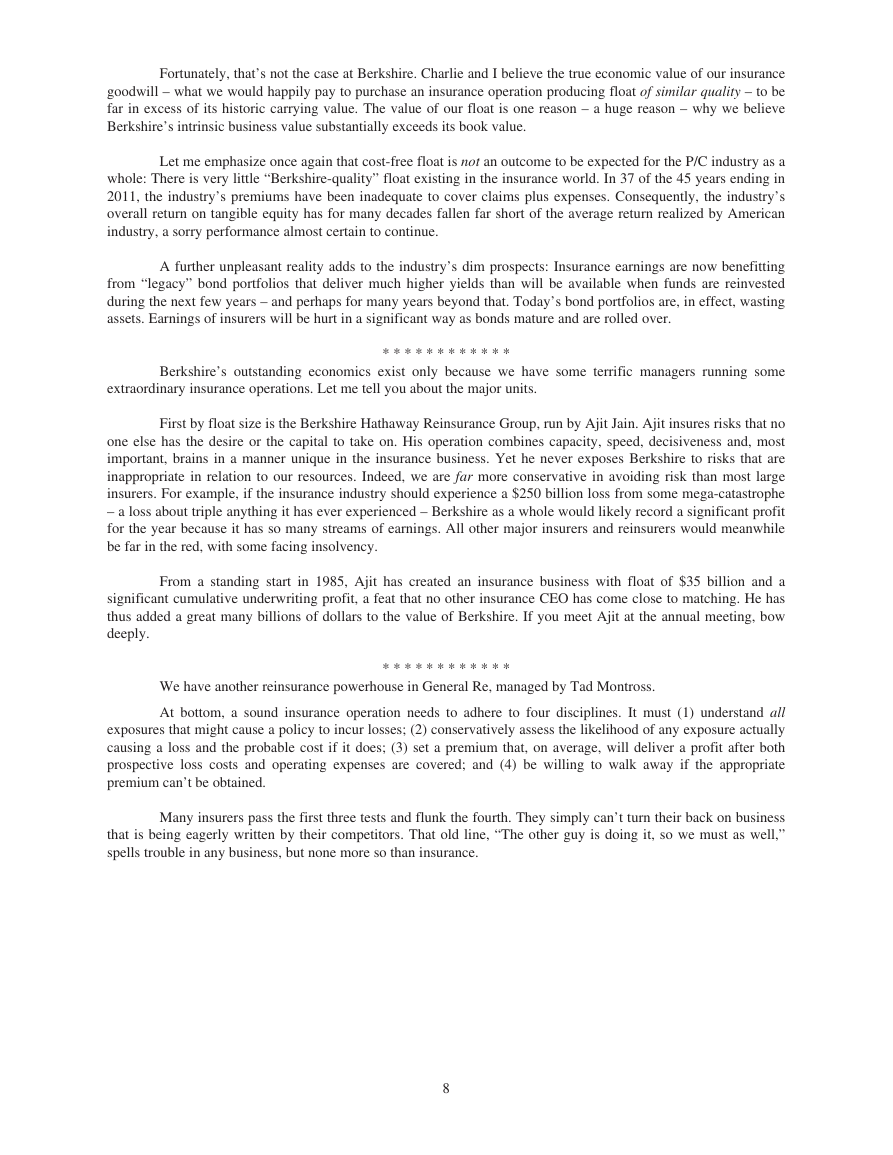

grows, so does our float. And how we have grown, as the following table shows:

Year

1970

1980

1990

2000

2010

2012

Float (in $ millions)

$

39

237

1,632

27,871

65,832

73,125

Last year I told you that our float was likely to level off or even decline a bit in the future. Our insurance

CEOs set out to prove me wrong and did, increasing float last year by $2.5 billion. I now expect a further increase

in 2013. But further gains will be tough to achieve. On the plus side, GEICO’s float will almost certainly grow. In

National Indemnity’s reinsurance division, however, we have a number of run-off contracts whose float drifts

downward. If we do experience a decline in float at some future time, it will be very gradual – at the outside no

more than 2% in any year.

If our premiums exceed the total of our expenses and eventual losses, we register an underwriting profit

that adds to the investment income our float produces. When such a profit is earned, we enjoy the use of free money

– and, better yet, get paid for holding it. That’s like your taking out a loan and having the bank pay you interest.

Unfortunately, the wish of all insurers to achieve this happy result creates intense competition, so vigorous

in most years that it causes the P/C industry as a whole to operate at a significant underwriting loss. This loss, in

effect, is what the industry pays to hold its float. For example, State Farm, by far the country’s largest insurer and a

well-managed company besides, incurred an underwriting loss in eight of the eleven years ending in 2011. (Their

financials for 2012 are not yet available.) There are a lot of ways to lose money in insurance, and the industry never

ceases searching for new ones.

As noted in the first section of this report, we have now operated at an underwriting profit for ten

consecutive years, our pre-tax gain for the period having totaled $18.6 billion. Looking ahead, I believe we will

continue to underwrite profitably in most years. If we do, our float will be better than free money.

So how does our attractive float affect the calculations of intrinsic value? When Berkshire’s book value is

calculated, the full amount of our float is deducted as a liability, just as if we had to pay it out tomorrow and were

unable to replenish it. But that’s an incorrect way to look at float, which should instead be viewed as a revolving

fund. If float is both costless and long-enduring, which I believe Berkshire’s will be, the true value of this liability is

dramatically less than the accounting liability.

A partial offset to this overstated liability is $15.5 billion of “goodwill” that is attributable to our insurance

companies and included in book value as an asset. In effect, this goodwill represents the price we paid for the float-

generating capabilities of our insurance operations. The cost of the goodwill, however, has no bearing on its true

value. For example, if an insurance business sustains large and prolonged underwriting losses, any goodwill asset

carried on the books should be deemed valueless, whatever its original cost.

7

�

Fortunately, that’s not the case at Berkshire. Charlie and I believe the true economic value of our insurance

goodwill – what we would happily pay to purchase an insurance operation producing float of similar quality – to be

far in excess of its historic carrying value. The value of our float is one reason – a huge reason – why we believe

Berkshire’s intrinsic business value substantially exceeds its book value.

Let me emphasize once again that cost-free float is not an outcome to be expected for the P/C industry as a

whole: There is very little “Berkshire-quality” float existing in the insurance world. In 37 of the 45 years ending in

2011, the industry’s premiums have been inadequate to cover claims plus expenses. Consequently, the industry’s

overall return on tangible equity has for many decades fallen far short of the average return realized by American

industry, a sorry performance almost certain to continue.

A further unpleasant reality adds to the industry’s dim prospects: Insurance earnings are now benefitting

from “legacy” bond portfolios that deliver much higher yields than will be available when funds are reinvested

during the next few years – and perhaps for many years beyond that. Today’s bond portfolios are, in effect, wasting

assets. Earnings of insurers will be hurt in a significant way as bonds mature and are rolled over.

Berkshire’s outstanding economics exist only because we have some terrific managers running some

extraordinary insurance operations. Let me tell you about the major units.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

First by float size is the Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance Group, run by Ajit Jain. Ajit insures risks that no

one else has the desire or the capital to take on. His operation combines capacity, speed, decisiveness and, most

important, brains in a manner unique in the insurance business. Yet he never exposes Berkshire to risks that are

inappropriate in relation to our resources. Indeed, we are far more conservative in avoiding risk than most large

insurers. For example, if the insurance industry should experience a $250 billion loss from some mega-catastrophe

– a loss about triple anything it has ever experienced – Berkshire as a whole would likely record a significant profit

for the year because it has so many streams of earnings. All other major insurers and reinsurers would meanwhile

be far in the red, with some facing insolvency.

From a standing start in 1985, Ajit has created an insurance business with float of $35 billion and a

significant cumulative underwriting profit, a feat that no other insurance CEO has come close to matching. He has

thus added a great many billions of dollars to the value of Berkshire. If you meet Ajit at the annual meeting, bow

deeply.

We have another reinsurance powerhouse in General Re, managed by Tad Montross.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

At bottom, a sound insurance operation needs to adhere to four disciplines. It must (1) understand all

exposures that might cause a policy to incur losses; (2) conservatively assess the likelihood of any exposure actually

causing a loss and the probable cost if it does; (3) set a premium that, on average, will deliver a profit after both

prospective loss costs and operating expenses are covered; and (4) be willing to walk away if the appropriate

premium can’t be obtained.

Many insurers pass the first three tests and flunk the fourth. They simply can’t turn their back on business

that is being eagerly written by their competitors. That old line, “The other guy is doing it, so we must as well,”

spells trouble in any business, but none more so than insurance.

8

�

Tad has observed all four of the insurance commandments, and it shows in his results. General Re’s huge

float has been better than cost-free under his leadership, and we expect that, on average, it will continue to be. We

are particularly enthusiastic about General Re’s international

life reinsurance business, which has achieved

consistent and profitable growth since we acquired the company in 1998.

Finally, there is GEICO, the insurer on which I cut my teeth 62 years ago. GEICO is run by Tony Nicely,

who joined the company at 18 and completed 51 years of service in 2012.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

I rub my eyes when I look at what Tony has accomplished. Last year, it should be noted, his record was

considerably better than is indicated by GEICO’s GAAP underwriting profit of $680 million. Because of a change

in accounting rules at the beginning of the year, we recorded a charge to GEICO’s underwriting earnings of

$410 million. This item had nothing to do with 2012’s operating results, changing neither cash, revenues, expenses

nor taxes. In effect, the writedown simply widened the already huge difference between GEICO’s intrinsic value

and the value at which we carry it on our books.

GEICO earned its underwriting profit, moreover, despite the company suffering its largest single loss in

history. The cause was Hurricane Sandy, which cost GEICO more than three times the loss it sustained from

Katrina, the previous record-holder. We insured 46,906 vehicles that were destroyed or damaged in the storm, a

staggering number reflecting GEICO’s leading market share in the New York metropolitan area.

Last year GEICO enjoyed a meaningful increase in both the renewal rate for existing policyholders

(“persistency”) and in the percentage of rate quotations that resulted in sales (“closures”). Big dollars ride on those

two factors: A sustained gain in persistency of a bare one percentage point increases intrinsic value by more than

$1 billion. GEICO’s gains in 2012 offer dramatic proof that when people check the company’s prices, they usually

find they can save important sums. (Give us a try at 1-800-847-7536 or GEICO.com. Be sure to mention that you are a

shareholder; that fact will usually result in a discount.)

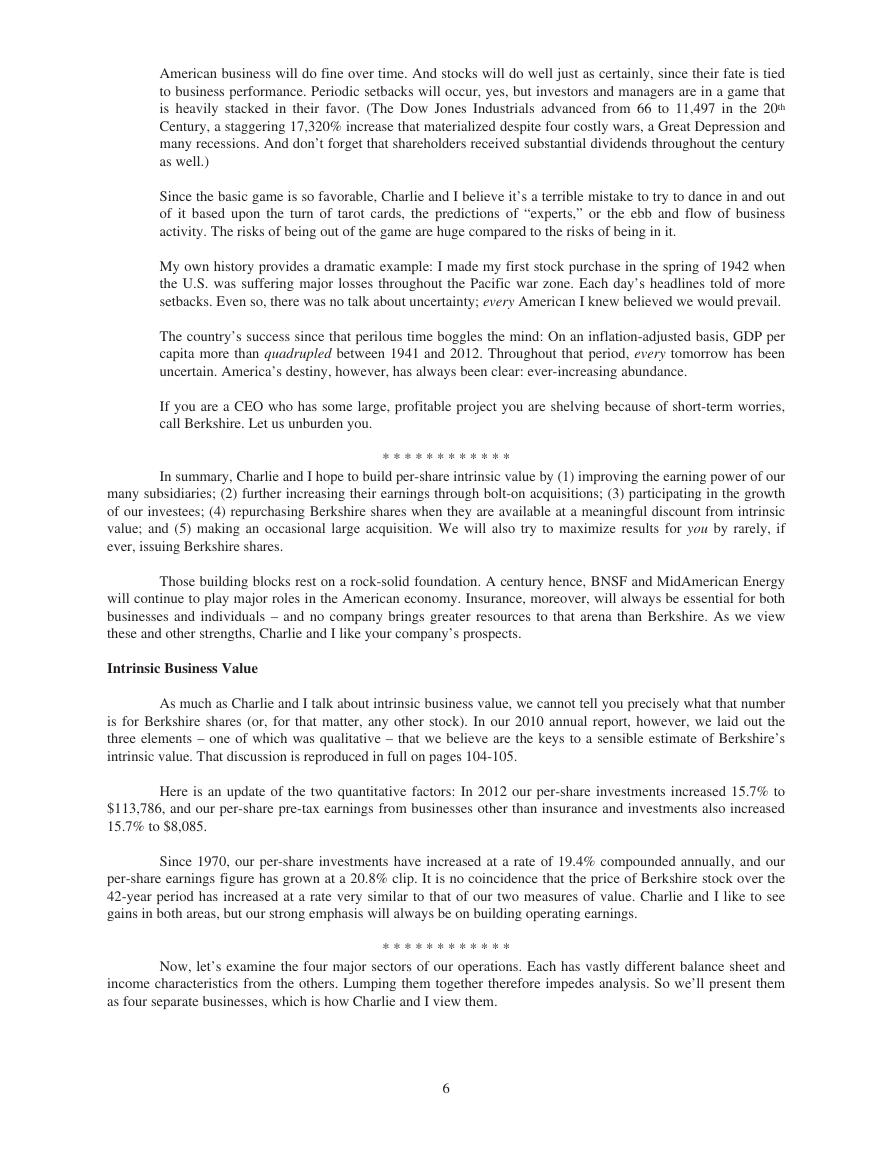

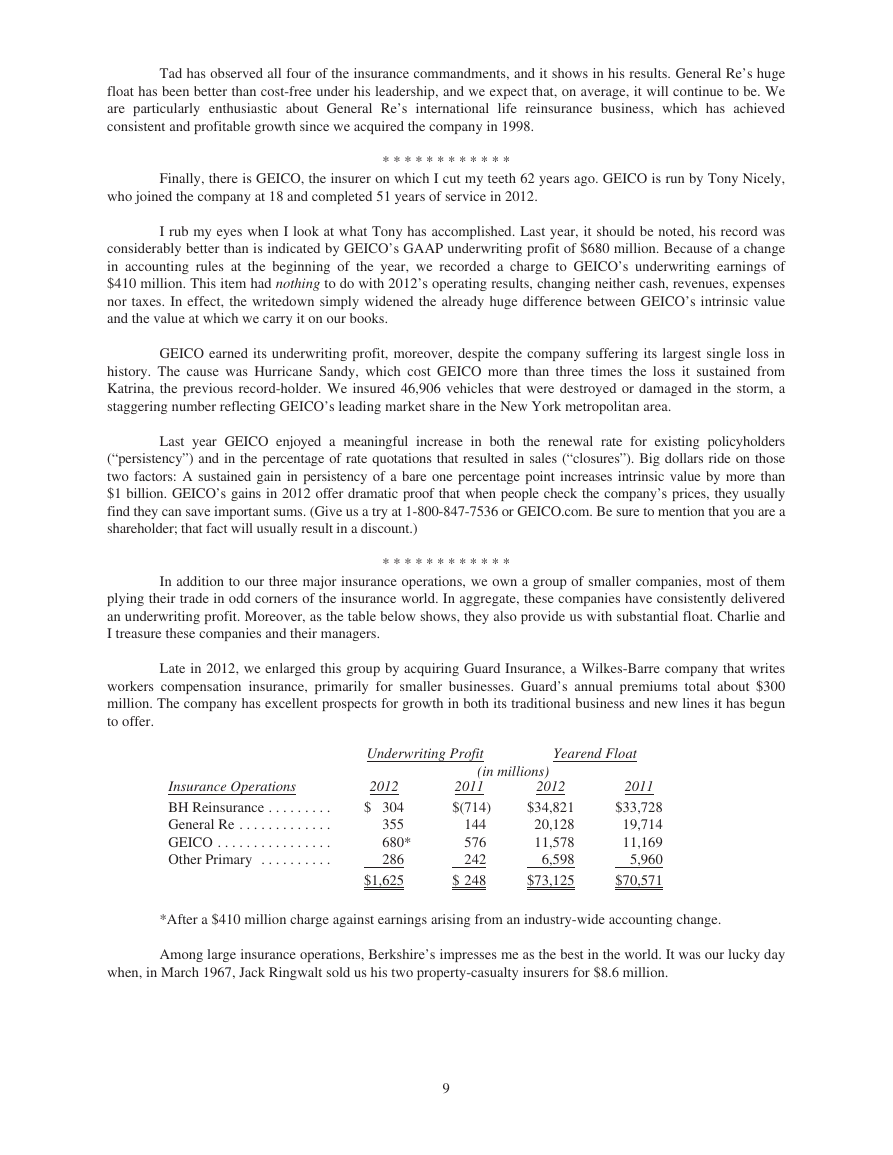

In addition to our three major insurance operations, we own a group of smaller companies, most of them

plying their trade in odd corners of the insurance world. In aggregate, these companies have consistently delivered

an underwriting profit. Moreover, as the table below shows, they also provide us with substantial float. Charlie and

I treasure these companies and their managers.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Late in 2012, we enlarged this group by acquiring Guard Insurance, a Wilkes-Barre company that writes

workers compensation insurance, primarily for smaller businesses. Guard’s annual premiums total about $300

million. The company has excellent prospects for growth in both its traditional business and new lines it has begun

to offer.

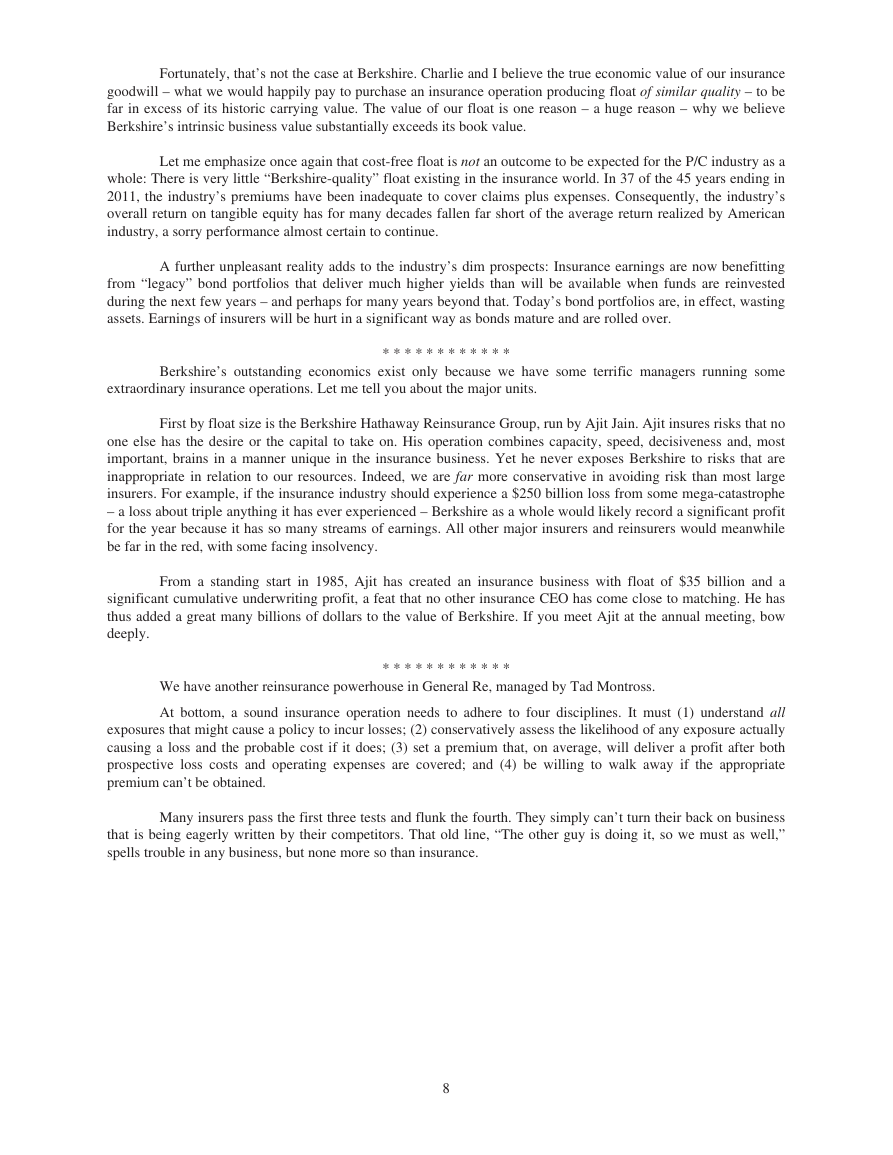

Underwriting Profit

Yearend Float

(in millions)

Insurance Operations

BH Reinsurance . . . . . . . . .

General Re . . . . . . . . . . . . .

GEICO . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Other Primary . . . . . . . . . .

2012

$ 304

355

680*

286

$1,625

2011

$(714)

144

576

242

$ 248

2012

$34,821

20,128

11,578

6,598

$73,125

2011

$33,728

19,714

11,169

5,960

$70,571

*After a $410 million charge against earnings arising from an industry-wide accounting change.

Among large insurance operations, Berkshire’s impresses me as the best in the world. It was our lucky day

when, in March 1967, Jack Ringwalt sold us his two property-casualty insurers for $8.6 million.

9

�